Brontë 200

As we mark the bicentenary of Emily Brontë’s birth, Sally Minogue sets her work in its cultural context – and in the social media world of 2018.

As I made a casual foray onto the web to get my bearings on the bicentenary of Emily Brontë’s birth 200 years ago, I discovered a mini Twitter storm around Kathryn Hughes’ piece (July 21st, The Guardian online on Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights (which she describes as a ‘hot mess’) and the way the bicentenary is being marked by the Brontë Parsonage Museum at Haworth, #Brontë200). Hughes’ memorably scratchy article was at least trying to get underneath, behind, through the resiliently resistive carapace of the Brontë myth. One of the troubles with that myth is that it is founded on rocks as eternal as those to which Cathy compares her love to Heathcliff. Charlotte, Branwell, Emily and Anne did live an enclosed and isolated life up to their adult years. Emily was three years old when her mother died; when she was seven, a pupil at Cowan Bridge School, her older siblings Maria and Elizabeth died of tuberculosis caught at the school. From that time the girls remained at home, with a father who was largely distant, and during this period they constructed their imagined world of Angria, in and around which they constructed fiction and poems. They did wander the moors; they did live their lives in a world of imagination; and they brought that world to the page (Emily and Anne in adulthood through another imagined world, that of Gondal) – finally in their adult fictions and poems, in which Emily led the way.

There’s quite enough there to make it extraordinary that all three women, Charlotte, Emily and Anne, produced some of the most sensational fiction of their own lifetime, but also the most lasting fiction of the two centuries since. Where the myth starts to get problematic is when commentators conflate that fiction with the lives. Hughes makes this very mistake herself, suggesting initially that Wuthering Heights is an autobiographical novel, and conflating Cathy with her creator Emily, suggesting that Brontë ‘is the girl who, on the evidence of Wuthering Heights, seems to have considered hanging a small dog an act of sexy foreplay’. I don’t want to get embroiled in all this speculation based on what we can’t know; but even so, I’d put money on the fact that Emily was a virgin who, sadly, knew nothing of sexy foreplay; and I bet Kathryn Hughes believes that too, whatever she writes. And come on – what’s with ‘the girl’? Wuthering Heights is so powerful precisely because it is a work of the imagination – written by a woman.

Well, the Twitterati can answer back, and they have. Hughes’ piece led me to Lily Cole, who is one of the celebrity fans that the Brontë Museum is bravely and rightly getting on board. Kate Bush is there too; alongside Carol Ann Duffy (for Charlotte), Jackie Kay (for Anne) and Jeanette Winterson (for all the Brontës), Bush has written a poem for Emily. Each poem is inscribed on a natural stone and is out there somewhere on the Yorkshire moors.

http://www.katebushnews.com

Not quite the eternal rocks, but a passable 21st version. Lily Cole (lilycole.com) in particular represents a more youthful generation; and if her piece on Heathcliff as a foundling is anything to go by, she is sage and well-informed and gives an interestingly fresh take on Emily Brontë. I visited the Foundlings’ Museum in London recently, but I hadn’t connected it with Heathcliff and Wuthering Heights. Now I will.

So, to my own view of Emily Brontë. In truth, I have always found Wuthering Heights a difficult novel to talk about, because I’m still stuck in the mind of the precocious but entirely inexperienced 16-year-old I was on first reading. For me, the novel reduces to three words: ‘I am Heathcliff’. This leaves an awful lot out – to be precise, 244 pages. Cathy’s passionate pronouncement (with its attendant irony that Heathcliff overhears her denunciation of him, but leaves before that declaration) takes place exactly a third of the way through the novel. The rest of the story stems from his misunderstanding, and there’s an awful lot of narrative unravelling to be done. Mine is the simple view of Wuthering Heights: romanticism at its most extreme, physical nature and human nature intertwined so deeply that there’s no metaphorical separation, Cathy and Heathcliff as almost supernatural beings who have an extra-bodily communication. And sex – what sex?

But there are many other readings of Wuthering Heights. Raymond Williams sees it socio-economically: ‘It is class and property that divides Heathcliff and Cathy, and it is in the positive alteration of those relationships that a resolution is arrived at in the second generation.’ (The Country and the City, 176) Kate Millett, writing of all the Brontë sisters, avers that ‘Literary criticism of the Brontës has been a long game of masculine prejudice wherein the player either proves they can’t write and are hopeless primitives … or converts them into case histories from the wilds, occasionally prefacing his moves with a few pseudo-sympathetic remarks about the windy house on the moors, or old maidhood, following with an attack on every truth the novels contain…’ (Sexual Politics, 147). Both readings are powerful reminders of the political and social context in which Brontë was writing, and also of that in which she has been read. And Williams and Millett (now themselves figures from the past, but a powerful past) also remind us of the changes that have taken place in our cultural thinking; indeed Millett’s male critic now looks like a straw man, as he has been replaced by so many formidable female critics and biographers. In those, I want to include Lily Cole, but also Kathryn Hughes. We know there’s something going on when we are irritated, discomfited, out of sorts, or simply cross with a writer. I think Emily Brontë would have been happy to be a thorn in her reader’s flesh two hundred years on. And a barbed Yorkshire thorn at that.

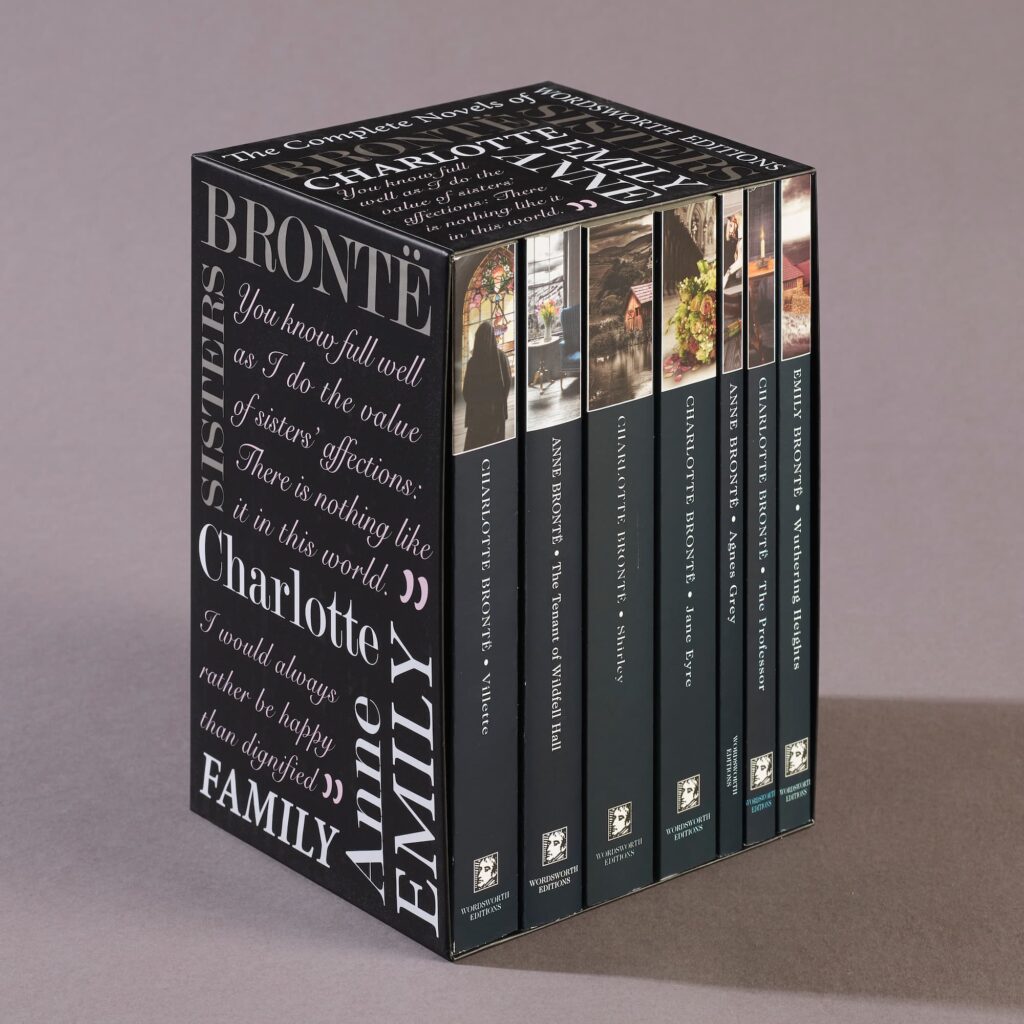

Books associated with this article

The Complete Brontë Collection

Anne BrontëCharlotte BrontëEmily Brontë