Discovering the pleasure of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure

Professor Cedric Watts examines one of Shakespeare’s most accessible and, in hindsight, contemporary plays.

I first read Measure for Measure a long time ago: March 1955, in my last year at school. Reading Shakespeare’s earlier comedies had sometimes been a chore; reading this one was a pleasure. (I read and noted it on a Saturday morning and afternoon; after which I spent the evening with a pretty and voluptuous girlfriend.)

Like many other school kids, I had long harboured a suspicion that Shakespeare might not be as good as he was always made out to be. At Measure for Measure, the suspicion vanished, even if the Shakespeare who spoke from the page wasn’t exactly the Shakespeare I’d been led to expect. The play offered realism, cynicism, bawdry, and a tough searching quality; it seemed odd, strange, jarring and aggressively intelligent, as though assailing conventional notions of comedy.

For example, there was the startling power of Claudio’s outburst to his sister in Act 3, scene 3:

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where;

To lie in cold obstruction, and to rot;

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bath in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbèd ice…

What made it seem startling was not only the vivid intensity of the utterance but also the stark contrast that this speech made to the recent homiletic advice of the Friar-Duke. I was reading the play in a cheap one-volume Complete Shakespeare with small type, so that those two speeches, though separated by about a hundred lines, were there in front of me, side by side, the Duke’s on the left-hand page, Claudio’s on the right. The Duke had eloquently and apparently authoritatively urged Claudio to a stoical acceptance of death:

Be absolute for death: either death or life

Shall thereby be the sweeter. Reason thus with life:

If I do lose thee, I do lose a thing

That none but fools would keep. A breath thou art…

It had seemed authoritative, that long speech, as it proceeded. And now, within a page, was a starkly conflicting view of life and death, death as a location of fantastic horror and surrealistic torment, life as a paradise in contrast. The Duke had seemed wise and conscientious, and he had spoken as a Friar, which surely gave hallowed authority to his homily. Yet Claudio was evidently the young hero of the plot, someone to regard sympathetically, and his eloquence had its own distinctive power, an impetuous force of image and tone. And there the two speeches were before me, side by side, saying totally opposed things. Who was right? One of them, neither, or in some elusive way both? What was certain was the deliberateness of the juxtaposition.

Thus, what dawned on me was that normal conventions of comedy were far less important in Measure for Measure than Shakespeare’s determination to challenge ethical thought and feeling together; to search deeply into big problems; to let the structure of the play be determined more by the intelligence of embodied argument than by the exigencies of orthodox structure and expected entertainment.

Arguments about life and death, sex and marriage, justice and authority: repeatedly the play dramatised extremes of viewpoint, making matters vividly problematic – and also contemporary. It seemed to reach into the 1950s and beyond them; for its boldness and incisiveness mocked the inhibitions and respectabilities which prevailed in the provincial England (particularly in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire) of 1955. I inwardly cheered both Pompey’s ‘Does your worship mean to geld and splay all the youth of the city?’ and Lucio’s ‘A little more lenity to lechery would do no harm’; and, as a proleptic rebuke to England in which capital punishment – the death sentence – was still operative, the presentation of Barnardine seemed to be one of the glories of the text.

You’ll remember how Barnardine is introduced. The Duke has been out-witted by Angelo, who, instead of waiving Claudio’s death sentence, orders the hastening of the execution; and the Duke seeks someone to be killed in Claudio’s stead. Barnardine seems designed by the plot to be the surrogate victim. But when the Duke encounters Barnardine, he encounters a distinctively living individual, stubbornly hung-over humanity; and the Duke can’t go through with his plan. He just can’t, when he meets the man, actually muster the determination to say ‘Off with his head!’. And eventually, the plot emits one Ragozine, a pirate who has conveniently died of fever, just in time for his head to be used as a substitute for Claudio’s.

As part of the plot, then, Barnardine seems to be redundant. Surely, a dramatist aiming for the narrative economy would have omitted him and proceeded directly to the news of Ragozine’s death. Therefore, the function of Barnardine is thematic and ethical. He is there to challenge the Duke, and thereby to challenge the very principle of capital punishment, of state-sanctioned judicial slaughter. Thus Shakespeare (as in Troilus and Cressida) was more than three hundred years ‘ahead of his times’.

So Measure for Measure seemed, in the 1950s, not ‘dark’, ‘morbid’, and full of ‘gloom and dejection’, as it had been termed, but healthily cogent. In the following decades grew the so-called ‘permissive society’ and its controversies: and they were the Measure for Measure controversies: about liberty versus licence, spontaneity versus control, old religion and new scepticism. These arguments continue. George Bernard Shaw was right when he said that in this play we find Shakespeare ‘ready and willing to start at the twentieth century if the seventeenth would only let him’. And its arguments continue forcefully into the twenty-first century.

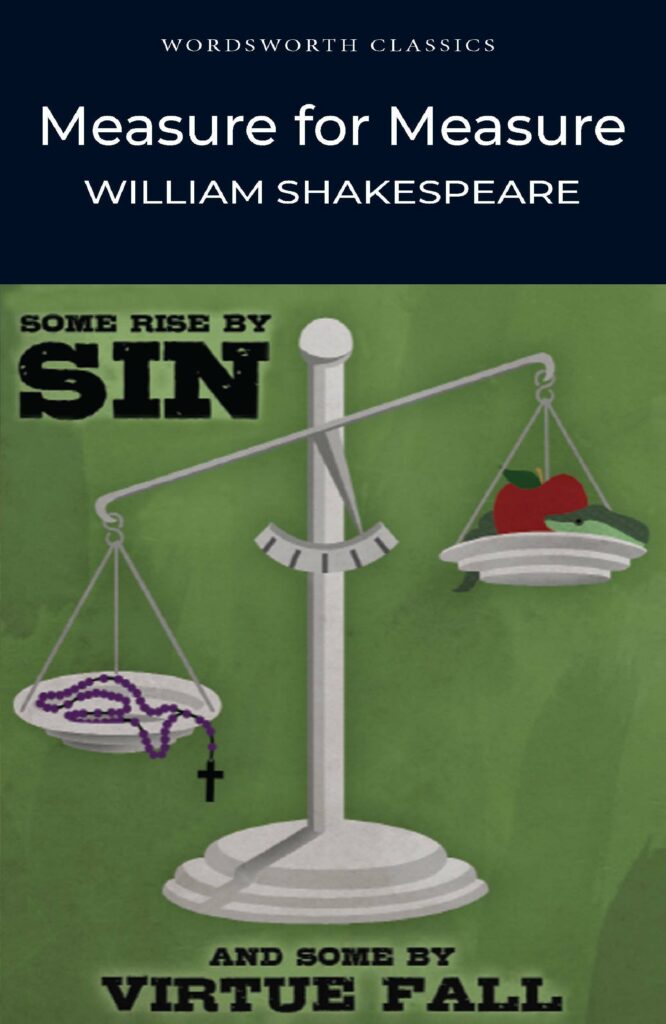

Measure for Measure was long neglected and much disparaged. Yes, it has its oddities and its flaws. But nowadays, to students and theatregoers, to amateurs and specialists, its cogent eloquence is loud and clear. In 2005, precisely half a century after I first read the play, it was an honour for me to be able to further that eloquence by editing Measure for Measure the Wordsworth Shakespeare Series. Still revised from time to time, that edition remains in print, making Shakespeare’s fiercely intelligent drama accessible to new generations.

By Cedric Watts, M.A. PhD Emeritus Professor of English, University of Sussex and Editor of Wordsworth Classics’ Shakespeare series

Books associated with this article