Share

-

Details

Other titles by William Shakespeare

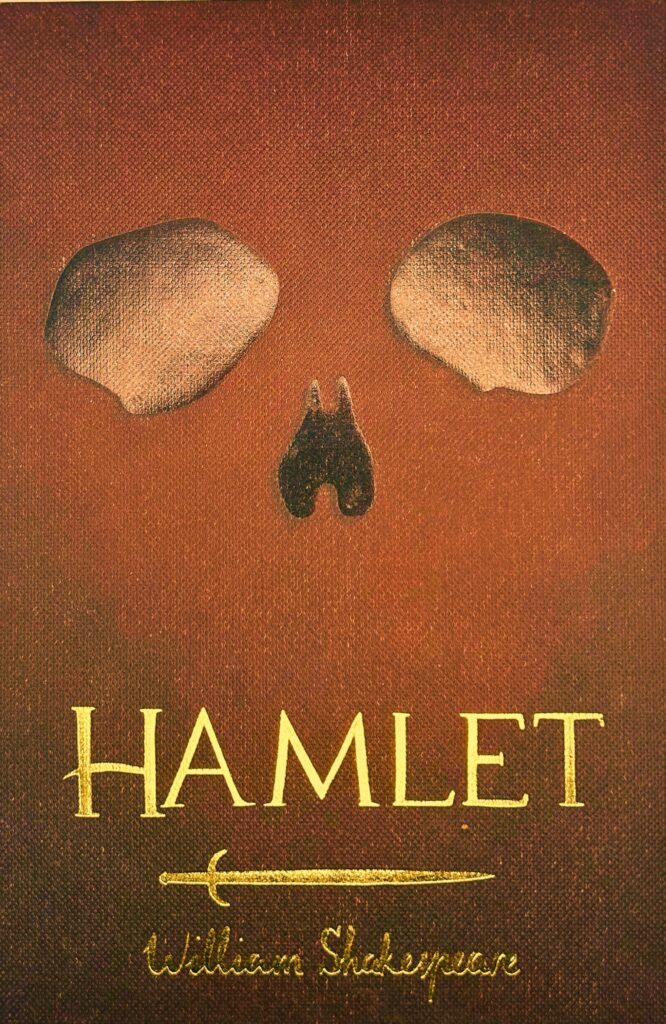

Hamlet (Collector’s Edition)

Collector's Editions

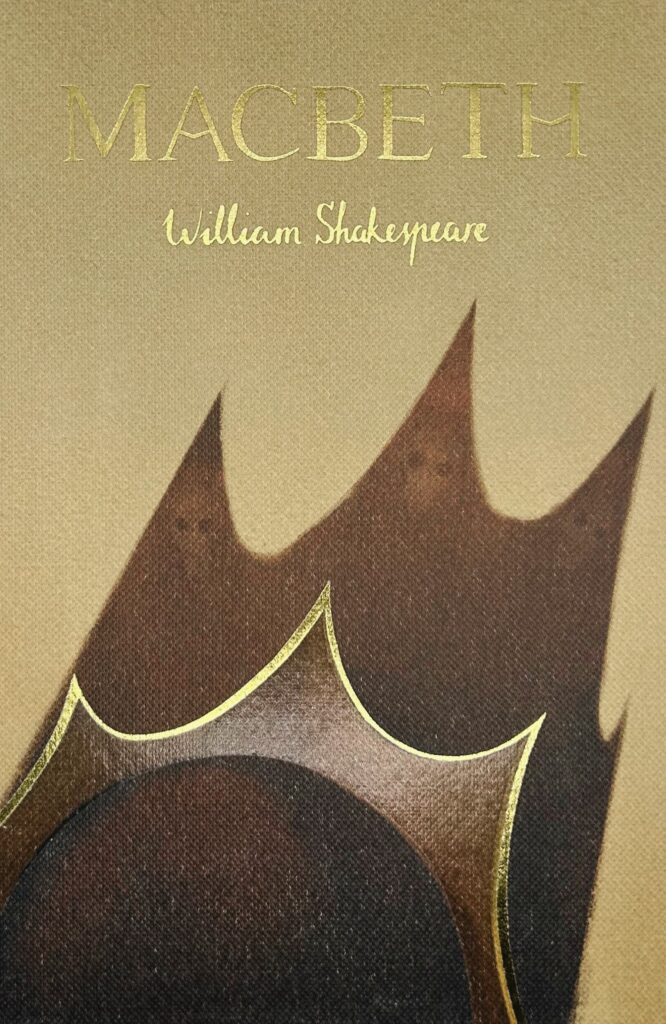

Macbeth (Collector’s Edition)

Collector's Editions

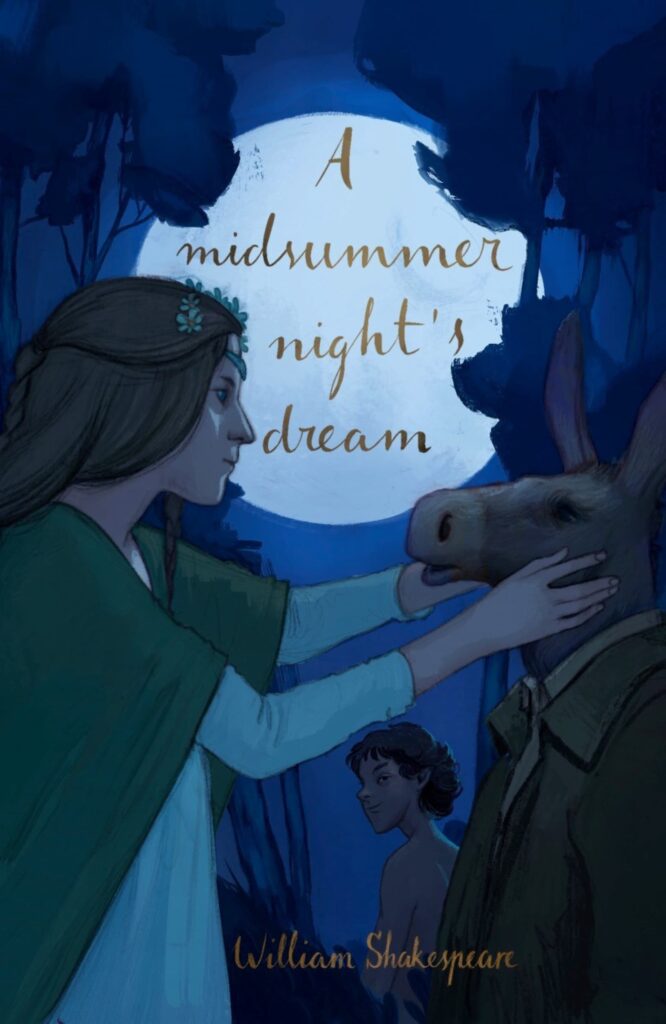

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Collector’s Edition)

Collector's Editions

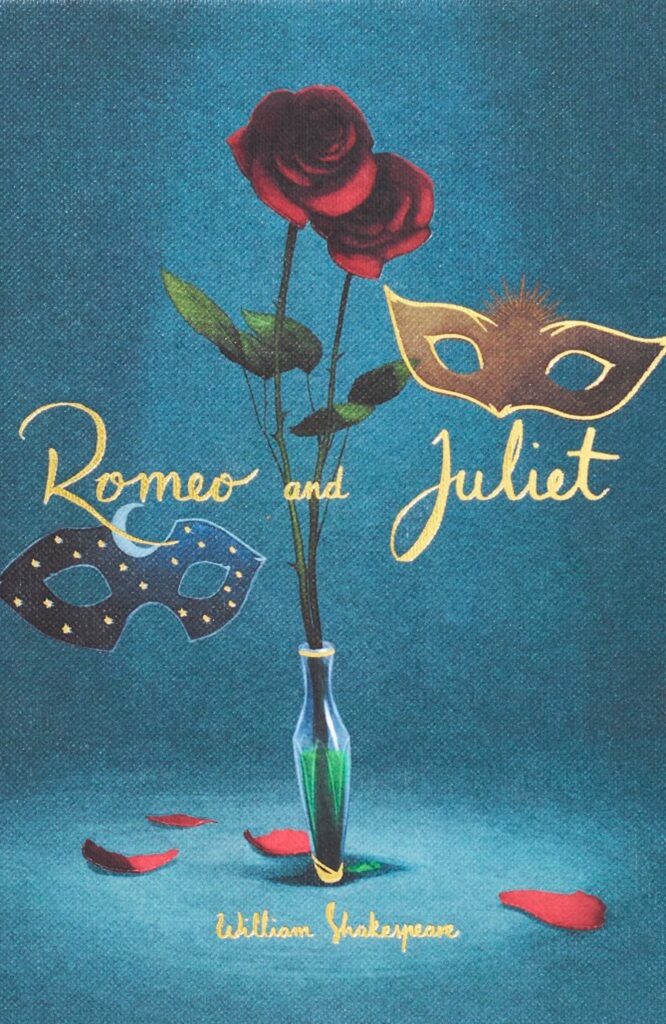

Romeo and Juliet (Collector’s Edition)

Collector's Editions

Antony and Cleopatra

Classics

As You Like It

Classics

Hamlet

Classics

Henry V

Classics

Julius Caesar

Classics

King Lear

Classics

Macbeth

Classics

Measure for Measure

Classics

The Merchant of Venice

Classics

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Classics

Much Ado About Nothing

Classics

Romeo and Juliet

Classics

The Taming of the Shrew

Classics

The Tempest

Classics

Twelfth Night

Classics

The Winter’s Tale

Classics

The Poems and Sonnets of William Shakespeare

Poetry

Richard II

Classics

Henry IV Parts 1 & 2

Classics