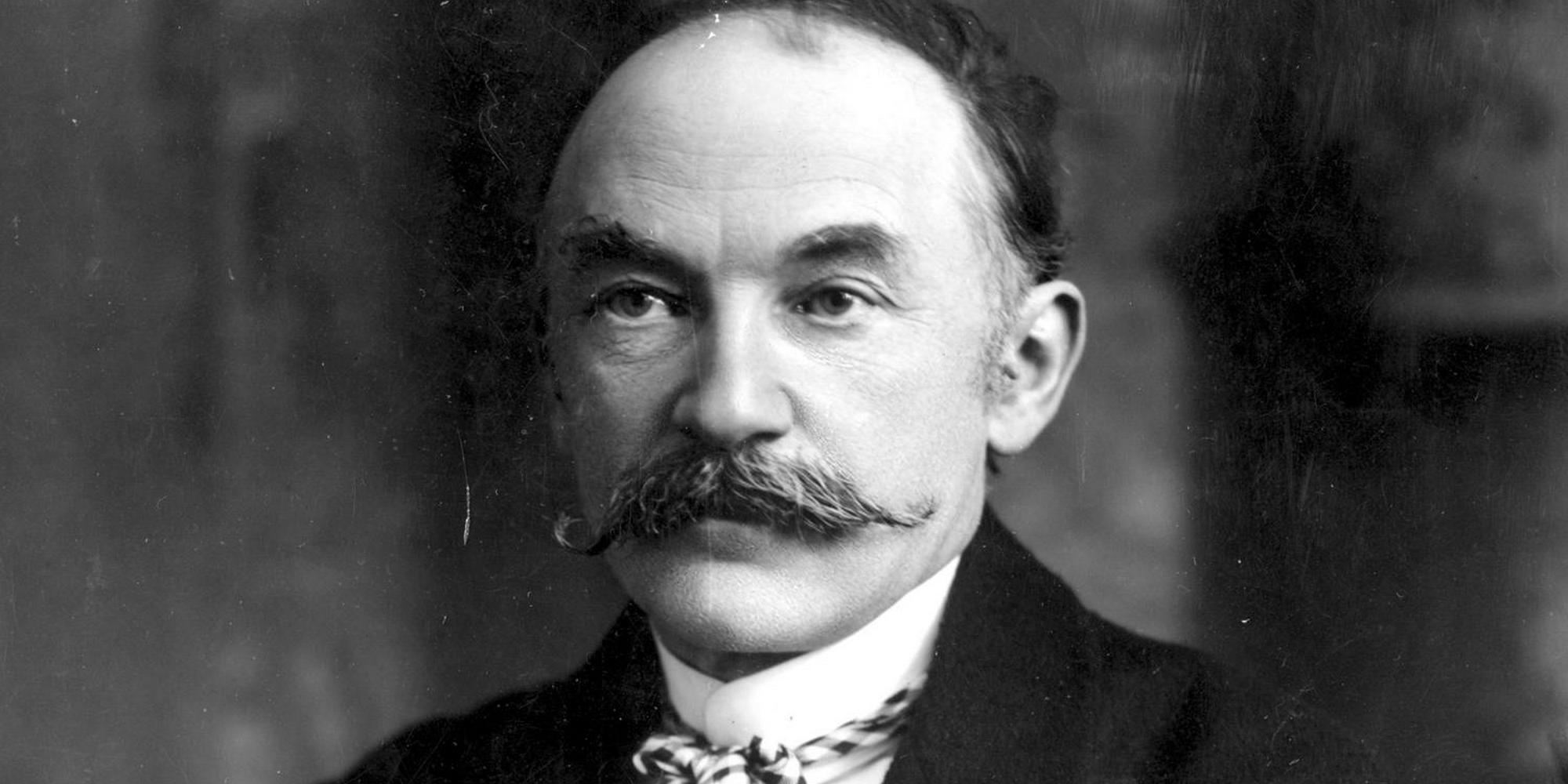

Thomas Hardy – 177 today

Sally Minogue offers some lugubrious birthday reflections as Thomas Hardy turns 177 today…

Why are anniversaries crucial points in remembering the people we remember? On this website we remember writers; it is their body of work which leads us to mark their anniversaries, of birth and death, which, through their work, have assumed public importance. But in our ordinary lives, we remember the people we have known most personally in all sorts of ways and at all sorts of moments – there is no knowing when their loss will come flooding. Even so, when that birthdate or death date comes around, it is an inexorable reminder that one we have loved exists no longer. Such moments also unsettle our own sense of ourselves, and we may have a more acute apprehension of our own mortality. These gloomy thoughts might seem a touch inappropriate for a celebration of Thomas Hardy’s birthday, but Hardy would have understood them entirely. One of his finest poems is ‘Your Last Drive’ (308), in which he addresses his just-dead wife, Emma, reflecting on the not-knowing of her impending death, and remembering that

On your left you passed the spot

Where eight days later you were to lie,

And be spoken of as one who was not;

The poem is addressed to Emma, but also, in reproach, to himself. He was the great poet of grief.

But he was also a connoisseur of gloom – and not any old gloom, but the existential variety that goes beyond the death awaiting us all, to that death reaching into life and reminding us of the abyss lying below even the most inconsequential acts of living. It is precisely that understanding which makes so much of his writing vivid, in the moment, an enactment of the actual, thrown into relief by the fact that it will necessarily come to an end. Hardy is England’s Proust: he can hold present and past in vertiginous equilibrium, whilst reflecting on their balance. He thus combines an awareness of the power of the past in the present and a proleptic understanding that the inevitability of death ahead undercuts all. Hardy’s prime medium for this is his lyric poetry – my subject in this post.

Hardy’s favoured trope is a detailed description of a present experience which calls up a remembered one, that remembered one then becoming the ‘real’ experience, because it has informed and transformed the present. Sometimes he reverses the process, beginning with the remembered experience which transmutes to the present. ‘Under the Waterfall’ (305) joins present and remembered past in one moment, that of plunging an arm into cold water. In the present, a basin of water; in the past, a living stream, where a glass shared by lovers was dropped irretrievably into the water, and lodged ‘in the crease of a stone’ beneath the waterfall. The incident recorded here actually happened when Hardy was courting his wife-to-be Emma Gifford; he sketched her at the time, her arm plunged into the stream to try to retrieve the drinking tumbler.

I’ve walked along the idyllic path they took in the Valency valley, and of course, I looked for the lost glass – in vain.

There the glass still is

And as said, if I thrust my arm below

Cold water in basin or bowl, a throe

From the past awakens a sense of that time,

And the glass we used, and the cascade’s rhyme.

The basin seems the pool, and its edge

The hard smooth face of the brook-side ledge,

And the leafy pattern of china-ware

The hanging plants that were bathing there.

‘There the glass still is’: a more conventional poet would have ‘There the glass is still’. Hardy instead throws the rhythmic emphasis onto ‘is’ at the end of the line: the lodged glass remains in the present tense. We hear too the tone of ordinary speech (emphasised by the fact that this poem is in fact a dialogue). And although Hardy enumerates the points of comparison between past event and present, drawing attention to their being distinct, the overall effect is to make them indistinguishable, as Proust does when he describes the tasting of the madeleine.

Hardy’s intense interest in the power of the past, here and elsewhere, is Wordsworthian, and this poem echoes Wordsworth’s ‘The Ruined Cottage’ with its ‘useless fragment of a wooden bowl’ lodged in ‘the slimy foot-stone’ of a spring, recalling a previous time when the bowl was whole and offered sustaining water to the passing visitor – a time now gone. The investment of spiritual and philosophical qualities in material things is entirely of that tradition. But whereas there is always in Wordsworth’s reflections on past time an underlying belief in the permanent power of nature to sustain human existence, Hardy does something different. He makes us as readers feel both the coincidence of past and present and the impossibility of reconciling them. At the end of ‘Under the Waterfall’, ‘There lies intact that chalice of ours’; but the speaking voice has moved forward from the moment. There is no sense of a continued fulfilment, only a moment of loss enshrined in the lodged glass. Suddenly that glass ‘Jammed darkly … its smoothness opalized’ ‘lours’ in the poem, an omen speaking both forwards from the past and backwards from the present. The loss of the glass is more powerful than the moment of loving unity that led to it, yet at the same time, it lies there beneath the waterfall, a testament to the loving moment that once took place. Wordsworth’s wooden bowl is broken, signifying the rupture between the old unified natural world and the present fragmented one; but Wordsworth continues to believe in the unified world and its power – that is precisely why the broken bowl matters. Hardy’s glass remains unbroken, but it petrifies in one moment both fulfilment and loss in a world of modernity where none of the natural sureties pertains. Hardy takes us into the modern consciousness fragmented by shifts in time, geography and perception.

Into this complicated self-reflection enters, at the very end of the poem, the realisation for the reader that the speaking voice in the poem is female (evident in the phrase ‘his and mine’). Then the domestic image of plunging an arm into a basin of water makes retrospective sense (and keeps us too in the world of actual sensation and the business of ordinary life, which always underpins Hardy’s philosophical reflection). But not before we have imagined the male persona doing the same thing: this is after all the male poet recalling an actual moment from his past, but transposing it to the imagination of his female lover.

A number of Hardy’s poems speak with a female voice – sometimes two, as in ‘The Ruined Maid’, which depicts a conversation between two women acquaintances who happen to meet after a time apart. Chatting, they catch up; and quickly it becomes apparent that the ’Melia addressed in the first stanza has found the high life, though only by being sexually ‘ruined’. The ironic interchange between the women is a brilliant interplay of poverty and morality, lightly and comically done. We feel we are hearing what those women at that time would have felt. ‘Ruined’ is turned from a term of shame to a synonym with comfort, warmth and security. And it is all lightly done – the poem makes us laugh:

‘I wish I had feathers, a fine sweeping gown,

And a delicate face, and could strut about Town!’ –

‘My dear – a raw country girl, such as you be,

Cannot quite expect that. You ain’t ruined,’ said she. (142)

This poem was written in 1866. Hardy was breaking convention by giving a voice not only to women, but also to women of a lower class, to a woman who had readily and knowingly exchanged sexual virtue for economic security and beyond that physical comfort, and to her counterpart who envied that from the position of ‘digging potatoes, and spudding up docks’. It’s a revolutionary poem. Twenty-two years later, Hardy embarked on his more fully felt, fictional exploration of what it was really like to be ‘ruined’. Tess of the D’Urbervilles, eventually published in full book form in 1892, is the tragic counterpart to ‘The Ruined Maid’. Poor Tess ends up as a ’Melia, but with a sense of honour utterly alien to hers, caught between the two voices in ‘The Ruined Maid’. Hardy’s subtitle for Tess – ‘A Pure Woman’ – stands between Tess’s fictional sacrifice on the altar of Victorian morality and the reader’s understanding that Hardy is condemning that, not endorsing it.

This aspect of Hardy’s work is what makes him truly great. He saw truths that were not told and he told them, first in his fiction and then – when his fiction was subjected to excoriating attack – in his poetry. The turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century marked almost exactly the turn he took from fiction to poetry. As ‘The Ruined Maid’ testifies, Hardy had been writing poetry for some time. But it was only when he gave up fiction, perhaps because of the Daily Mail-esque outcry against his final novel Jude the Obscure, that he dedicated himself to poetry. The result was a body of work which set the poetic tone for the twentieth century; Hardy was from the start modern in attitude and poetic approach and influenced a number of later poets (most notably Philip Larkin – see Introduction viii). Yet he reverted constantly to archaism, to traditional forms, to an idiosyncratic voice, witness ‘The Convergence of the Twain’ (278), Hardy’s extraordinary response to the sinking of the Titanic whose vocabulary and rhetoric might strike the modern reader oddly. Looking at it on the page now as I write, it seems ridiculously slight: eleven three-line stanzas barely spanning two pages. Not much to set against the vast arrogance of the Titanic and the profound repercussions of its sinking. But if we imagine this poem appearing, as it did, in the programme of a high-profile fund-raising event on May 14th 1912, exactly one month after the disaster, its terms are shocking. It would be like a contemporary poet writing about 9/11 in terms of the hubris and greed of American capitalism and imperialism, and reading it out at a commemorative event. (In fact, the poet laureate of New Jersey at the time, Amiri Baraka, wrote just such a poem from a radical black point of view, causing a public outcry. For an account of this and other 9/11 poems, see poetryfoundation.org.

In Hardy’s poem, there’s not an iota of sympathy for those who died; rather their ‘vaingloriousness’ and ‘human vanity’ are mocked as their fate is described. ‘The convergence’ of the title, the coming together of the ship and its ‘sinister mate’ the iceberg, is depicted as a ‘consummation’, whose connotations of sexual fulfilment and satisfaction Hardy exploits through the sustained metaphor of marital union. To see the sinking as a tragedy is, for him, to misread and underplay something far more significant – the inevitable and perversely ‘intimate welding’ of the human and the natural. That brutal word ‘welding’ reminds us of the technology of modernity from which both the conception and the actuality of the Titanic sprang, but which had its roots in the massive Victorian investment in industrial engineering. In this way, the poem, depicting the clash of humans over-reaching with the eternal powers of nature, has its roots in the nineteenth century. But within it to we hear Hardy’s voicing of the wrenching and rupture which lay ahead in the twentieth-century world – even the hellish cacophony and cataclysm of the First World War seems to echo in the collision that ‘jars two hemispheres’.

Hardy is an extraordinary writer: his work reflects what he himself experienced, the move from theology, ethics and understanding of the world that was pre-Darwinian (Hardy was 19 when The Origin of Species was published), to one that, by the time he died in 1928, had absorbed post-Darwinian uncertainties, been shaken by the First World War, and had begun to undergo the revolution of thought that was modernism. Yet for the best of Hardy’s poetry, turn to his Poems of 1912-13 (307-325) which are entirely personal. They reflect, agonisingly, on the loss of his first wife Emma, from whom he was effectively estranged when she died, even though they were living in the same house, the architectural and social expression of his success as a writer, Max Gate. In these poems, Hardy plunges back into the time when he first knew her, bringing her back so vividly to himself and to the reader that it is as though the young much-loved and loving Emma, ‘with your nut-coloured hair, / And grey eyes, and rose-flush coming and going’ (317), has returned to replace the dead, and in fact unloved, wife. The irony of these poems, in which both Emma and his love for her are revivified through grief, is that they can occur only after her death. Hardy was ever the writer; one can’t help feeling that, however genuine the feelings of remorse he had after she died, he seized on them as only a writer could. For one so sensitive to the ironic relationship between past and present, so aware of the power of memory and consciousness to transform experience, and with such an intense understanding of the waywardness of human emotion– here he had found his perfect subject and his true modern voice.

It’s this that calls to us now as readers. Knowing that the great poet had walked that path by the river Valency, and knowing the tale of the lost glass, of course, drew me, as many others, to retrace his steps. But at the heart of that retracing is the poem which recreates his and Emma’s experience. ‘Under the Waterfall’ is so much more than the experience which initiated it; like many of Hardy’s poems, it speaks to us across more than a century, but in a voice that we recognise as ours.

Page numbers refer to our edition of ‘The Collected Poems of Thomas Hardy‘

Books associated with this article