The Witch’s Curse: Elizabeth Gaskell and the Female Gothic

Something for Halloween… The Witch’s Curse

In the great pantheon of Victorian British literature, Elizabeth Gaskell is among its most versatile authors. Of course, she will always be associated with her powerful industrial novels Mary Barton and North and South. But there is also the progressive social protest of Ruth – a contentious novel in its own day, ruffling even more establishment feathers than had Mary Barton – as well as the affectionate comedy of Cranford, the historical romance of Sylvia’s Lovers, the Austenesque genius of Wives and Daughters, and her frank and sensitive biography of her close friend Charlotte Brontë. What is perhaps less known now than it was in her own day, however, is Gaskell’s contribution to the Victorian Gothic.

It’s easy to think of Gaskell as primarily a social critic, a ‘Condition of England’ novelist, but she is also one of a group of British women in the long 19th century – Romantic to Modernist – who made a significant contribution to the development of modern literary horror; writers such as Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Catherine Crowe, Margaret Oliphant, Charlotte Riddell, Amelia Edwards, Dora Sigerson Shorter, H. D. Everett, ‘Vernon Lee’ (Violet Paget), Edith Nesbit, and May Sinclair. Gaskell was, in fact, a significant exponent of the ‘Female Gothic’, a term coined by the American literary theorist Ellen Moers in Literary Women in 1976 to define the way women writers in the 18th and 19th centuries used gothic narrative as a coded way to describe and explore anxieties over motherhood, domestic entrapment and female sexuality. The Female Gothic is concerned, for example, with the gendered constructions of the gothic heroine and gothic hero, the link between the gothic space – haunted houses, ruined castles, labyrinthine dungeons, and wild, sublime landscapes – and female sexuality, and the conflation of issues of wealth and social rank with issues of femininity. The Witch’s Curse

Gaskell’s contribution to the Female Gothic is celebrated in the Wordsworth Editions collection Tales of Mystery & the Macabre (edited by the late David Stuart Davis), which contains a broad selection of Gaskell’s uncanny and supernatural fiction, most notably ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’, a ghost story with a feminist edge, the double story ‘The Poor Clare’, and her disturbing novella Lois the Witch, a Victorian forerunner of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible.

That Gaskell should write in this genre is hardly surprising. As a child, Elizabeth Cleghorn Stevenson loved ghost stories and regional folklore and was renowned at school for her ability to tell scary stories. This was a talent that never left her; as Anne Thackeray Ritchie (W.M. Thackeray’s eldest daughter) later recalled:

My sister and I were once under the same roof with her in the house of our friends Mr. and Mrs. George Smith, and the remembrance of her voice comes back to me, harmoniously flowing on and on, with spirit and intention, and delightful emphasis, as we all sat indoors one gusty morning listening to her ghost stories. They were Scotch ghosts, historical ghosts, spirited ghosts, with faded uniforms and nice old powdered queues … spiritual and unseen; mystery was there, romantic feeling, some holy terror and emotion, all combined to keep us gratefully silent and delighted. The Witch’s Curse

Conversely, Charlotte Brontë found these stories so disturbing she preferred not to hear them. As Elizabeth recalled in her Life of Charlotte Brontë:

One night I was on the point of relating some dismal ghost story, just before bed-time. She shrank from hearing it, and confessed that she was superstitious, and prone at all times to the involuntary recurrence of any thoughts of ominous gloom which might have been suggested to her.

Charlotte, of course, gave the Female Gothic Jane Eyre, the ‘Madwoman in the Attic’ Bertha Mason becoming a potent symbol of patriarchal repression and feminist rebellion. Her sister Emily’s Wuthering Heights, meanwhile, is a ghost story that goes beyond the traditional genre to challenge Victorian Christian morality and the English class system, with a physical passion that lasts beyond the grave.

Though a good, rational Unitarian girl (who married a Unitarian minister), fully accepting the teaching of Joseph Priestley that ‘men cannot embrace as sacred truth anything against which their common sense revolts,’ Elizabeth was also quaintly superstitious, a quality that seemed to coexist with her nontrinitarian rationality. This can be seen quite clearly in a letter she wrote to her friend Mary Howitt in 1838:

A shooting star is unlucky to see. I have so far a belief in this that I always have a chill in my heart when I see one, for I have often noticed them when watching over a sick-bed and very, very anxious. The dog-rose, that pretty libertine of the hedges with the floating sprays wooing the summer air, its delicate hue and its faint perfume, is unlucky. Never form any plan while sitting near one…’The Witch’s Curse

(Mary Howitt was the wife of Gaskell’s first publisher, Willian Howitt, and author of the famous poem ‘The Spider and the Fly’.) She also told Mary she knew a man who had ‘seen the Fairies.’ Similarly, she once wrote to her publisher George Smith that ‘being half-Scotch I have a right to be very superstitious; & I have my lucky & unlucky days, & lucky & unlucky people.’ There is also a letter to close friend Eliza Fox chronicling a visit to Shottery, near Stratford-on-Avon in 1849, where on a long drive ‘to a place where I believed the Sleeping Beauty lived, it was so over-grown and hidden up by woods,’ Elizabeth writes, ‘I SAW a ghost! Yes I did; though in such a matter of fact place as Charlotte St I should not wonder if you are sceptical.’ Without providing any more detail, she immediately adds, ‘and had my fortune told by a gypsy; curiously true as to the past at any rate.’

Her head full of ghosts and folktales, Elizabeth’s first (anonymously) published story, ‘Clopton Hall’, in William Howitt’s Visits to Remarkable Places (1840), was based on a Poe-like legend she’d picked up in childhood:

In the time of some epidemic, the sweating-sickness, or the plague, this young girl had sickened, and to all appearance died. She was buried with fearful haste in the vaults of Clopton chapel, attached to Stratford church, but the sickness was not stayed. In a few days another of the Cloptons died, and him they bore to the ancestral vault; but as they descended the gloomy stairs, they saw by the torch-light, Charlotte Clopton in her grave-clothes leaning against the wall; and when they looked nearer, she was indeed dead, but not before, in the agonies of despair and hunger, she had bitten a piece from her white round shoulder!

The story concludes, ‘Of course, she had walked ever since.’The Witch’s Curse

After Mary Barton launched Gaskell into the world of the professional writer in 1848 – juggled with the roles of mother and clergyman’s wife – she was courted by Dickens as a potential contributor to his new weekly journal, Household Words. Gaskell sent him ‘Lizzie Leigh’, the story of a country girl seduced and abandoned in the city, where she is forced into prostitution, a kind of reimagined prequel to Esther’s narrative in Mary Barton. It appeared in the first issue on March 30, 1850, and was serialised in three parts, for which Gaskell was delighted to receive a fee of £20. She was so busy with family and social work that Dickens had to actively pursue Gaskell for another story, ‘The Well of Pen Morfa’ (a tale of love, loss, and the power of belief), which he didn’t get until November. From this point on, Dickens became the primary publisher of Gaskell’s shorter works, so we have him to thank for her gothic output. Cranford was also first serialised in Household Words between 1851 and 1853. In the present collection, only ‘The Doom of the Griffiths’ and ‘Curious If True’ didn’t appear first in a Dickens’ periodical.

While throughout the year, Household Words ran articles debunking dodgy mediums and accounts of apparitions, for Dickens, Christmas was a time for ghost stories. He therefore published an extra Christmas number of Household Words in 1852 entitled A Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire which included Gaskell’s ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’, one of her few uncanny tales to include a ghost. In it, she drew on the experience of visiting a ruined mansion in Lancashire once owned by a prominent 17th century dissenter. She had mentioned this in the same letter to Mary Howitt in which she described her interest and belief in regional folklore and superstitions:

Lord Willoughby, The President of the Royal Society, and author of some book on natural history … left two daughters, and the estates were disputed and passed away to the male heir by some law of chicanery.

When Elizabeth visited the hall while walking with some friends, part of it was occupied by a farming family, while the main house was locked and derelict. When she asked if the group might be allowed into the deserted mansion to explore, the farmer’s wife reacted like a Transylvanian peasant who has just been asked by a tourist the way to Dracula’s castle:

The woman of the place looked aghast at this proposal, for it was twilight, and said that: ‘Lord Willoughby walked, and every evening was heard seeking for law-papers in the rooms where all the tattered and torn writings were kept.’

In ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’, Lord Willoughby becomes ‘Lord Furnivall’, again the father of two daughters, though the passion of his unquiet spirit is for music, playing a great organ in the hall, a moment of pure horror coming when the narrator discovers it ‘all broken and destroyed inside.’The Witch’s Curse

The frame of the story is that of the ‘old nurse’, Hester, telling her young charges (in the second person, therefore addressing us) about their mother, Rosamund’s, childhood, when Hester looked after her as a baby though only a teenager herself. This opening follows M.R. James’ later rule that ‘For the ghost story a slight haze of distance is desirable … we listen to it the more readily if the narrator poses as elderly, or throws back his experience.’ Rosamund was orphaned young and sent to live at Furnivall Manor in Cumberland, the home of an elderly, unmarried and distant relative, Miss Grace. Hester insists on accompanying her. The east wing is never opened and ‘The windows were darkened by the sweeping boughs of the trees’; this is a perfect gothic setting in which the young heroine (whether we take that to be Rosamund or Hester or both) finds herself isolated in an unfamiliar environment that becomes increasingly threatening. Miss Grace’s sister, Maude, is long dead and for some reason her portrait is turned to the wall. The mysterious organ music is put down to atmospheric conditions though ‘folks did say it was the old lord playing,’ the housekeeper, Dorothy, confides, but ‘I was never to say she had told me.’ Hester learns to ignore the strange music ‘which did one no harm, if we did not know where it came from.’ Yet this is only a prelude, not the story. As a harsh winter rolls in, Rosamund insists she keeps seeing a little girl outside in the snow beckoning to her to come out:

‘She won’t let me open the door for my little girl to come in; and she’ll die if she is out on the Fells at night. Cruel, naughty Hester,’ she said, slapping me; but she might have struck harder, for I had seen a look of ghastly terror on Dorothy’s face, which made my very blood run cold.

And so, by degrees, the dark family secret is revealed, stemming from the rivalry between the two sisters for the same man a lifetime ago leading to a single act of cruelty that has haunted Grace ever since.

Still from the film Salem’s Lot 1979

David Stuart Davis has likened the ghostly child outside the window to Cathy’s ghost in Wuthering Heights, while I was reminded of The Turn of the Screw (with perhaps a dash of Danny Glick in Salem’s Lot). Like The Turn of the Screw, male authority is absent – at least among the living – and Hester and Dorothy are left to deal with the problem, though its root is patriarchal. Rosamund’s cousin, the present Lord Furnivall does not live at the manor and has nothing to do with his ward. Instead, it is Hester, the working-class girl, who saves the day, and discovers the true fate of Maude at the hands of her sister and father. Though the cast of the story is almost entirely female, it is the presence of the old Lord Furnivall that still dominates them. It is thus a story of the exploitation and abuse of women by men until they are manipulated into turning on each other, though the supernatural threat birthed by this tragedy strengthens the bonds between the female servants as they fight to save Rosamund.

In the long past of the story, meanwhile, the gothic heroine is Maude, her story an exploration of emergent sexuality, another key theme in the Female Gothic. As the American academic Nina da Vinci Nichols wrote of the gothic heroine and setting in her 1983 paper ‘Place and Eros in Radcliffe, Lewis, and Brontë’: ‘Her progress, therefore, from adolescence to maturity simultaneously weds plot to the central theme of emotional identity and demands that circumstantial, outward strangeness speak for the more perilous strangeness of her unknown inner self.’ Published while Cranford was ongoing in Household Words, it is interesting to note that ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’ shares the same theme of the bonds between women, though through very different means.

‘The Poor Clare’ (Household Words, 1856) is Gaskell’s other long supernatural story. The title refers to the Order of Saint Clare, an enclosed order of Roman Catholic nuns. It is often referred to by critics as a second ‘ghost story’, but the apparition at its heart is a doppelgänger:

Just at that instant, standing as I was opposite to her in the full and perfect morning light, I saw behind her another figure—a ghastly resemblance, complete in likeness, so far as form and feature and minutest touch of dress could go, but with a loathsome demon soul looking out of the gray eyes, that were in turns mocking and voluptuous. My heart stood still within me; every hair rose up erect; my flesh crept with horror. I could not see the grave and tender Lucy—my eyes were fascinated by the creature beyond. I know not why, but I put out my hand to clutch it; I grasped nothing but empty air, and my whole blood curdled to ice. The Witch’s Curse

As with ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’, the mischievous and sexually charged double is no more the main point of the tale than was Lord Furnivall’s organ. Rather, ‘IT’ is the outcome of a long, complex and tragic family history in which a curse delivered against an enemy inadvertently hurts a loved one. The source and solution to this problem is narrated by an unnamed London lawyer who has fallen for the haunted Lucy while researching a complex inheritance case. The mystery is why the ‘pure and holy Lucy’ is the victim of the ‘powers of darkness.’

Again like ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’, ‘The Poor Clare’ is set in the past, with a long backstory attached to it that reaches further back still. (As ever, Gaskell’s character creation and world building is masterful.) In common with the earlier story, it involves the sexual deception and betrayal of a woman by a man, a recurring theme in Gaskell’s writing, seen in the fate of Esther in Mary Barton, the title character of Ruth, Maude Furnivall, and the protagonist of ‘The Grey Woman’, another gothic tale. While the plot is notionally driven by the dramatic need of the narrator to free Lucy from the curse so they can marry, the central character is Bridget Fitzgerald, an elderly, reclusive and eccentric working-class woman who has lost touch with her daughter, Mary, who disappeared in Europe having written that she was to marry a gentleman. The narrator of the tale has discovered that Bridget is the heir to the estate he represents, and has promised to help her find her daughter…

Bridget is a formidable presence in the story. To the locals, ‘she was unconsciously earning for herself the dreadful reputation of a witch,’ while the narrator sees a ‘wild, stern, fierce, indomitable countenance, seamed and scarred by agonies of solitary weeping’ but ‘neither cunning nor malignant.’ Bridget is another of Gaskell’s strong women seeking agency and justice in a stratified and patriarchal society. After Mary vanished, all that remained of her was her dog, Mignon, which Bridget loved as a surrogate for her daughter, until it was shot by Squire Gisborne, a guest on a hunting party organised by the local landowner. Having no recourse but to heaven, Bridget brings down a curse on the indifferent and shallow nobleman:

‘You shall live to see the creature you love best, and who alone loves you—ay, a human creature, but as innocent and fond as my poor, dead darling—you shall see this creature, for whom death would be too happy, become a terror and a loathing to all, for this blood’s sake. Hear me, O holy saints, who never fail them that have no other help!’

This curse, however, rebounds in some terrible and unexpected ways. It is not until the narrator tracks Bridget to the ‘Poor Clares’ in Antwerp years later that the full truth comes to light against the dramatic backdrop of the Flemish rebellion against Austrian occupation.

‘The Poor Clare’ is an elegant, spiritual, and politically charged story. Like the Furnivall sisters, the patriarchal social order oppresses Bridget and her family, until the women unwittingly turn on each other. As Jenny Uglow wrote in her 1993 biography of Gaskell, ‘In many of Gaskell’s short stories women themselves create misery through the very strength of their feelings,’ continuing, ‘This female chain of consequence is expressed in the witch’s curse.’ In ‘The Poor Clare’, Bridget’s curse is the last resort of a women rendered powerless by class and gender, but, as the saying goes, ‘Seek revenge and you should dig two graves.’ While Gaskell’s tale indicates the author’s deep dissatisfaction with the position of women in a patriarchal culture, she also shows the inherently destructive nature of vengeance, especially on the innocent. The curse can only be lifted by forgiveness, suggesting a tension between Gaskell’s faith and her gender politics, although the possibility of rebellion remains in the final setting of the story. The Witch’s Curse

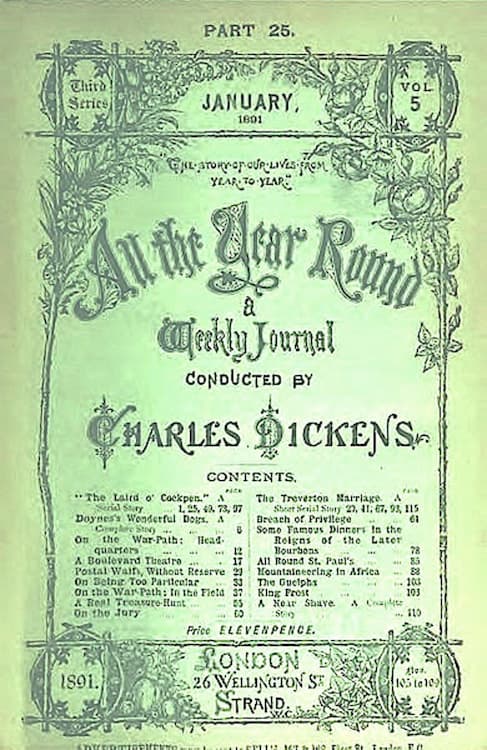

All the Year Round

Gaskell returns to the witch’s curse in her most powerful gothic story, Lois the Witch, a 36,000-word novella first published in three parts in All the Year Round (Dickens’ successor to Household Words) in 1859. The story follows the Radcliffian model of the gothic in that a young female protagonist is displaced from the familiar (representing childhood) to an unknown alien landscape (adulthood and emerging sexuality) and subjected to some kind of sexual threat by a brooding male villain. Like Radcliffe’s gothic fiction, there is nothing ultimately supernatural about the tale, only an air of brooding menace and key-bending suspense. Unlike Radcliffe, there’s no fairytale ending in which a hero emerges to marry the heroine (he turns up too late in the third act), while just to make Lois the Witch even more disturbing, it’s based on the true story of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692–93.

The orphaned Lois Barclay, a vicar’s daughter from Warwickshire, is sent to live with her mother’s Puritan brother and his family in Salem, Massachusetts, leaving behind her sweetheart, Hugh Lacy, whose parents disapproved of the match and thought better of offering her a home. The ‘New World’ seems ancient and primitive, standing in for the medieval European Catholic settings of the 18th century gothic. At the Widow Smith’s house, for example, Lois’ first stop upon arrival in America:

The aspect of this room was strange in the English girl’s eyes. The logs of which the house was built, showed here and there through the mud plaster, although before both plaster and logs were hung the skins of many curious animals,—skins presented to the widow by many a trader of her acquaintance, just as her sailor guests brought her another description of gift—shells, strings of wampum-beads, sea-birds’ eggs, and presents from the old country. The room was more like a small museum of natural history of these days than a parlour…

She is also warned by an old sailor that ‘it is not safe to go far into the woods, for fear of the lurking painted savages’ while ‘the seashore is infested by pirates, the scum of all nations.’

During an awkward dinner at which is present an austere Puritan elder, the mention of witches prompts Lois to blurt out a childhood memory about seeing a local woman being ‘ducked’ that becomes the first curse of the story:

‘I saw old Hannah in the water, her grey hair all streaming down her shoulders, and her face bloody and black with the stones and the mud they had been throwing at her, and her cat tied round her neck. I hid my face, I know, as soon as I saw the fearsome sight, for her eyes met mine as they were glaring with fury—poor, helpless, baited creature!—and she caught the sight of me, and cried out, “Parson’s wench, parson’s wench, yonder, in thy nurse’s arms, thy dad hath never tried for to save me, and none shall save thee when thou art brought up for a witch.”’

While Elder Hawkins shakes his head and quotes scripture, Mrs. Smith tries to lighten the mood by ominously joking that, ‘And I don’t doubt but what the parson’s bonny lass has bewitched many a one since, with her dimples and her pleasant ways.’ Already, Lois is marked, and her beauty is likely to be another curse. As Hawkins darkly concludes, ‘my mind misgives me at her story. The hellish witch might have power from Satan to infect her mind, she being yet a child, with the deadly sin.’ The Witch’s Curse

When Lois arrives in Salem, no one is expecting her (her dying mother’s letter has been delayed), and her uncle is on his deathbed. Her aunt, Grace, begrudgingly takes her in, and Lois struggles to connect with her three cousins: the dreamy Faith, the mischievous Prudence, and their brooding elder brother, the cadaverous Manasseh, who stares at her disconcertingly and speaks like an Old Testament prophet. The settlement is surrounded by forest and Nattee, an old Native American servant, terrifies Lois with tales of ‘the wizards of her race’ who live there, and can summon a ‘double-headed snake … that had such power over all those white maidens who met the eyes placed at either end of his long, sinuous, creeping body, so that loathe him, loathe the Indian race as they would, off they must go into the forest to seek but some Indian man, and must beg to be taken into his wigwam, abjuring faith and race for ever.’

The Salem Witch Trials

The family cabin feels sticky with repressed desire. Faith is carrying a silent torch for Pastor Nolan, and mixes love potions with Nattee, though the young priest clearly has eyes for Lois. So does the creepy Manasseh, who has a vision that: ‘I saw a gold and ruddy type of some unknown language, the meaning whereof was whispered into my soul; it was, “Marry Lois! marry Lois!” And when my father died, I knew it was the beginning of the end. It is the Lord’s will, Lois, and thou canst not escape from it.’ Manasseh’s ‘spirit of prophecy’ in fact denotes madness. Grace knows this, but can’t accept the fact:

With wilful, dishonest blindness, she would not see—not even in her secret heart would she acknowledge, that Manasseh had been strange, and moody, and violent long before the English girl had reached Salem. She even found some specious reason for his attempt at suicide long ago. He was recovering from a fever—and though tolerably well in health, the delirium had not finally left him.

It is easier to blame Lois, who meantime struggles to politely keep Manasseh at arm’s length while trying to help Faith with Nolan. Faith, meanwhile, becomes increasingly jealous, and Manasseh’s visions get more violent:

‘Only this last night, camping out in the woods, I saw in my soul, between sleeping and waking, the spirit come and offer thee two lots, and the colour of the one was white, like a bride’s, and the other was black and red, which is, being interpreted, a violent death. And when thou didst choose the latter the spirit said unto me, “Come!” and I came, and did as I was bidden. I put it on thee with mine own hands, as it is preordained, if thou wilt not hearken unto the voice and be my wife. And when the black and red dress fell to the ground, thou wert even as a corpse three days old.’

After a very long winter, the witch mania breaks out in Salem…

Gaskell creates a terrifying world of superstition and religious enthusiasm, building tension through the disturbing character development of the Puritans and their society, and the isolation and austerity of the environment, until the barely repressed violence, delusion, and hysteria finally explode. Lois tries always to be Christian, kind, and rational – her character representing the author’s Unitarian values – but as the forces marshalling around her build towards inevitable climax, the message is clear: if you were denounced in 17th century Salem, the verdict was pretty certain. Her accusers are Faith, Prudence, and Grace. The Witch’s Curse

Gaskell’s authorial voice seems to look back to the stupid ages from her position as an enlightened Victorian, with direct textual interventions such as ‘And you must remember, you who in the nineteenth century read this account, that witchcraft was a real terrible sin to her, Lois Barclay, two hundred years ago.’ Yet at the same time she is undoubtedly inviting the reader to examine the dangers of dogma and Calvinist theology, which was as present in the 19th century as it was in the 17th, with its belief in original sin and the divinely appointed salvation of the elect, whereas a public affirmation of Gaskell’s own faith had only become legal in England in 1813.

Gaskell was getting a lot of her history from the American politician and Salem historian Charles Wentworth Upham. A Massachusetts Senator, Upham had become an expert on the Witch Trials after being elected Mayor of Salem. In 1831, he had published Lectures on Witchcraft Comprising a History of the Delusion in Salem in 1692 (the first of three books he wrote on the subject, the others appearing after Lois the Witch). Harriet Martineau had reviewed Upham’s book in the Unitarian journal the Monthly Repository. Martineau’s resonant conclusion made much the same point Gaskell would appear to be making in Lois the Witch: ‘it is true that the times are so far ameliorated that the plague of superstition cannot ravage society as formerly. But society is not yet safe.’ As Gaskell’s early literary pseudonym was ‘Cotton Mather Mills’ (Cotton Mather was a Puritan clergyman and author who Nathaniel Hawthorne later described as ‘the chief agent of the mischief’ at Salem), it is clear that Salem’s dark and bloody history had made an impression.

The persecution of so-called ‘witches’ is a potent symbol of institutionalised misogyny and patriarchal oppression. While making this fact implicit, Gaskell also explores the ways in which women could become complicit in their own subjugation through the false accusations of Lois’ aunt and cousins. Finally, she uses Lois’ response to these accusations to represent the Unitarian ideals of universal love and rational belief. Lois the Witch is an elegant work of Female Gothic, perhaps almost as nuanced and deeply philosophical as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein itself.

Though space does not allow me to cover them in depth here, the other stories in this collection are equally worthy of attention. In ‘The Squire’s Story’, the flamboyant gentleman who rents the ‘White House’ in the small 18th century town of Barford is not at all what he seems. ‘The Doom of the Griffiths’ conflates the legends of Owain Glyndŵr – the leader of the medieval Welsh Rebellion – and the earlier Welsh Prince, Rhys ap Gruffydd, in a dark tale of infanticide and patricide framed by an ancient family curse. ‘The Ghost in the Garden Room’ (AKA ‘The Crooked Branch’) is another Christmas story written for All the Year Round. Eerie and tragic by turns, Gaskell uses the story to again explore the deception and betrayal of women by men. This theme is perhaps most fully realised in ‘The Grey Woman’, a ‘found manuscript’ in which a young woman is trapped into marriage by a foreign nobleman with a sinister secret and must escape with the aid of a resourceful female servant while relentlessly pursued by her violent husband. There is a change of pace with the light-hearted magic realism of ‘Curious, if True’, which will no doubt make fans of Angela Carter and Alan Moore smile. Finally, ‘Disappearances’ is a nonfiction piece for Household Words made up of true stories of people who just vanished (a format familiar to modern followers of True Crime), probably inspired by the loss of Elizabeth’s brother, John, at sea in 1828.

Among many other good reasons for visiting this collection – it is Halloween, after all – it is the sheer variety of the stories that impresses. At the same time, all can be viewed through the lens of the Female Gothic, the genre offering a form of narrative in which that which could not be said by women in Victorian realism becomes sayable in dark Victorian fantasy. This collection is thus an invaluable asset to the study of women’s writing, Victorian literature, and of Mrs. Gaskell herself. If you’re more familiar with her social realism, Gaskell’s gothic fiction will give you a new way of seeing this author and interpreting her more well-known novels. This is also a collection for all lovers of the Victorian gothic, the esoteric, the mad, and the macabre. As the ‘Old Nurse’ laments, ‘I wish I had never been told, for it only made me more afraid than ever.’ The Witch’s Curse

For more information on the life and works of Elizabeth Gaskell, visit: The Gaskell Society . Our edition of Tales of Mystery and the Macabre can be found here

Main image: Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire, UK. Credit: Christopher Jones / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Still from the 1979 film Salem’s Lot, directed by Tobe Hooper. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Examination of a Witch, 1853 painting by Tompkins Matteson depicting a scene from the Salem Witch Trials. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Cover of magazine 3rd series ‘All the Year Round’ magazine by Charles Dickens , 1891. Credit: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

The Witch’s Curse The Witch’s Curse The Witch’s Curse The Witch’s Curse The Witch’s Curse The Witch’s Curse The Witch’s CurseThe Witch’s Curse

Books associated with this article