‘He do the Police in different voices’

As Charles Dickens’ last complete novel, Our Mutual Friend, is adapted for BBC Radio 4, Sally Minogue looks at the novel’s relationship to his world and to ours.

I’ve just spent a few days in London, where this blog was very much on my mind. In Our Mutual Friend (1865), as often in Dickens’ novels, nineteenth-century London is landscape, plot device, and central abiding character. Our contemporary city, with its cranes rising above the skyline like skeletal birds of prey, apartment buildings and office blocks thrusting yet aimless in our post-Covid anti-city world, jostling each other for primacy as they suck the air and the light from the ground below, a nouveau riche counterpoint to the elegant spires and domes of the old city – this London nonetheless remains remarkably the same London that Dickens knew. Key to this is the river. ‘Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song’, wrote Edmund Spenser in the sixteenth century – and also wrote T. S. Eliot in the twentieth, stealing Spenser’s words in that way that modernism allowed as an ironic re-reading, through a tapestry of voices, in his iconic poem The Waste Land. That poem is germane to this blog, since Eliot’s working title for it was ‘He Do the Police in Different Voices’, a line taken from Betty Higden’s description in the Our Mutual Friend of Sloppy’s reading of the newspaper. Betty is praising Sloppy’s ability to inhabit different characters or institutions by using different voices. This was grist to the mill for Eliot; but it was likewise for Dickens. Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

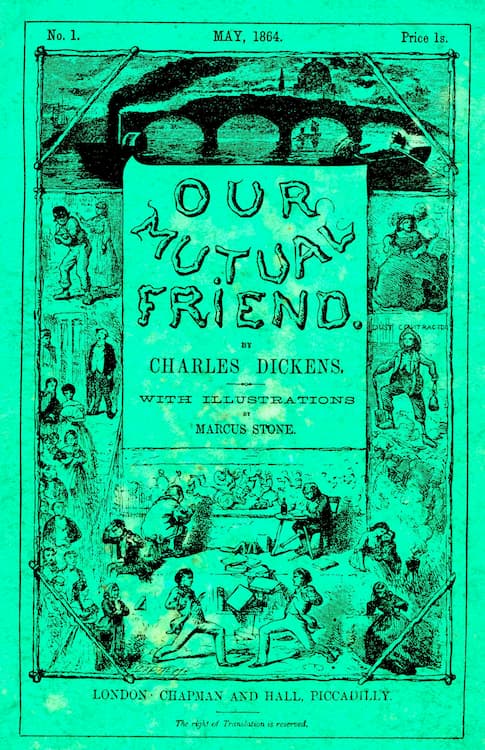

Front cover of the first instalment of ‘Our Mutual Friend’ 1864

Our Mutual Friend is full of different voices, often used to delineate differences of class. But it also employs the idea of adopting a different voice (and face to society) to give a new idea of the self. In this novel Dickens shows us a world where either a fate is expected but never happens, or where a fate comes about which is unexpected and unimagined. In both situations, the characters involved have to adapt themselves to their suddenly different circumstances. Dickens shows the human tendency in such situations to resort to camouflage, or in some cases downright impersonation. But then where is the true person? This of all Dickens’ novels comes closest to a modernist understanding of the slippage of the self. At rare but significant times in the novel we see behind the public or assumed face and into the ‘real’ consciousness of a character (sometimes expressed in narratively experimental ways). Yet at the same time Dickens exercises many of his usual tricks of comic exaggeration and caricature, extreme coincidence and sudden plot revelation, of a sort that militates entirely against the complex reflections, uncertainties and intimations of spiritual despair which he suggests elsewhere. On the one hand we have extreme cartoon figures – as in the ‘bran-new people in a bran-new house Veneerings’ (Ch 2) or the pompous Podsnaps; on the other, we have a sense of the void, in the grasping world, in the life of society, in the self, in the depths of the river, in death itself.

Those names – the brilliantly conceived ‘Veneerings’, the absurdly mimetic ‘Rogue Riderhood’, the dark implications of ‘Bradley Headstone’ – are characteristically ‘Dickensian’, a shorthand way of encapsulating the character. This was a particularly useful device in such a sprawling and highly-populated novel, published in serial monthly instalments, so that readers had need of means to quickly mark out and remember individual characters. Sometimes this shorthand seems too improbably apt, as in ‘Jenny Wren’ for the dolls’ dressmaker; though here there is a doubling, since she has adopted that name for herself, while her real name is Fanny Cleaver – another performative name, but one opposite in association to the meek ‘Jenny Wren’. Only Dickens could get away with such nominative determinism. But this is after all fiction, and determinism is the name of the game; it is Dickens who both names Fanny Cleaver and in turn allows her to ‘choose’ the soubriquet Jenny Wren which so fits her body and persona. Dickens himself described writing the novel as ‘getting back to the large canvas and the big brushes’, and the headline names are one form of his broad brushstrokes. But the ‘large canvas’ also refers to large themes and the bigger picture. While his characters play out their lives often at a minutely detailed level, we are also made aware of the novelist’s larger vision. Sometimes this involves a literal panning out, sometimes a closing in to a reflective inner consciousness. In the very first, highly atmospheric, paragraphs of the novel the narrator takes the larger view, positioning his readers alongside him:

In these times of ours, though concerning the exact year there is no need to be precise, a boat of dirty and disreputable appearance, with two figures in it, floated on the Thames, between Southwark Bridge which is of iron, and London Bridge which is of stone, as an autumn evening was closing in.

Then we close in to see the figures in the boat, ‘a strong man with ragged grizzled hair and a sun-browned face, and a dark girl of nineteen or twenty … recognizable as his daughter.’

Allied to the bottom of the river rather than the surface, by reason of the slime and ooze with which it was covered, and its sodden state, this boat and the two figures in it obviously were doing something that they often did, and were seeking something they often sought. Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

Lizzie and Gaffer

By the end of the third paragraph we learn that even the ‘look of dread or horror’ on the girl’s face becomes one with these customary actions: ‘they were things of usage’. Thus we are introduced to the Hexams’ dreadful trade of pulling corpses from the river, taking the money from their pockets, advertising their find and sometimes earning a fee when they are identified. It is a thing of usage, a customary trade. Lizzie, horrified as she is by this life, has no choice but to participate in it. Some fourteen chapters later, and with events ebbing and flowing as regularly as the river tide itself, Gaffer Hexam is himself pulled from the river and, ‘dead some hours’ laid ‘stretched upon the shore’, in an uncanny echo of the many corpses he has himself dredged up. And now we move from the exterior view to a profound interiority, expressed in a sort of stream of consciousness as the narrative voice takes both an external and a subjective position:

Father, was that you calling me? Father! I thought I heard you call me twice before! Words never to be answered, those, upon the earthside of the grave. The wind sweeps jeeringly over Father, whips him with the frayed ends of his dress and his jagged hair, tries to turn him where he lies stark on his back, and force his face towards the rising sun, that he may be shamed the more. A lull, and the wind is secret and prying with him; lifts and lets fall a rag; hides palpitating under another rag; runs nimbly through his hair and beard. Then it cruelly taunts him. Father, was that you calling me? Was that you, the voiceless and the dead?

The natural assumption when we begin this passage is that this is somehow the inner voice of Gaffer’s daughter Lizzie (not actually present in the scene), but as the passage progresses it seems to be the taunting voice of nature itself, and of the winds that toy teasingly with his corpse, as they breathe apparent life into the form beneath the rags, lifting them in a mocking imitation of a heartbeat. Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

Mr. Riah and Miss Wren at the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters

So Our Mutual Friend is on the one hand sometimes crudely and comically caricaturish and on the other frankly existential, expressionist and experimental, and this amalgam has been a challenge both to Dickens’ contemporary audience and to today’s modern readership. It is also possibly the most complex of the writer’s narratives as he sought to balance those broad expressionist brushstrokes with a semi-realist account of the lives of both the upper and the lower strata of society. London is presented as a glittering city with greed at its heart, and the river running through it as both the stream of life, and a latter-day Styx leading to the Underworld. As the river gives up its corpses and they are exchanged for money, so the rubbish of the teeming city accumulates and the trade of dealing with it is the source of the fortune that lies at the heart of the novel’s highly convoluted plot. Bella Wilfer, the central female character, begins as a woman obsessed by her ill fortune in losing the promise of that money. The man she was to marry dies just as he is about to inherit the Harmon fortune, an inheritance that was by the terms of the will dependent on his marrying Bella. She thus loses both a husband and a fortune in one stroke. But rather like Shylock losing his daughter Jessica (‘My ducats! Oh my daughter! Oh my ducats!’), she is more concerned with the money than the man. Reflecting on the absurdity of her situation, widowed before she has even been married, made poor again before she was ever rich, she cries:

“It was ridiculous enough to know I shouldn’t like him – how could I like him, left to him in a will, like a dozen of spoons, with everything cut and dried beforehand, like orange chips … Those ridiculous points would have been smoothed away by the money, for I love money, and want money – want it dreadfully. I hate to be poor, and we are degradingly poor, offensively poor, miserably poor, beastly poor.’

In a world where there are such gulfs between rich and poor, one can’t blame Bella here; she sees only too clearly the differences between what she might have had and what she is left with. She will change in this respect, and that is one of the slow turning points of the novel. This is a Dickens novel that depends more even than usual for its effectiveness on the withholding and revealing of information, and surprises and coincidences of narrative, so I am at pains not to discover too much of the plot to the potential reader. But love, money and death are all intimately tied together here, and sometimes it seems that the greatest of these is money.

The next-in-line inheritor of the fortune that Bella sees disappearing from her grasp is Boffin, who has been a lowly worker for his ‘guvnor’ Harmon, but through the accidental inheritance becomes the Golden Dustman of the novel. Making gold from the detritus of the business of living, allied with making money from the detritus of the human body, provides Dickens with a gift of a metaphor for the corrupt and corrupting nature of money. But the Boffins are exemplars of good. They will make themselves happy with their money – but only so far. They will do something for Bella, who has been robbed by their good fortune. They will adopt a poor orphan and make a good life for the child. If Dickens’ characteristic sentimentality enters here, nonetheless we are glad of this counter-example to the cupidity of so many in the novel.

The clock tower of Southwark Cathedral

My London perambulations led me to Southwark Cathedral –right next door to the Southwark Bridge and the very stretch of river mentioned on that first page of Our Mutual Friend. This was Shakespeare’s own church; he was a recorded parishioner, and there is a fine monument to him, showing him reclining rather louchely – in so far as you can in alabaster. Amazing to think, as I walked around, that he would have occupied that same space. We were there to see Luke Jerram’s Gaia, a huge model of our planet Earth as it can be seen only from outer space. By a clever sleight of hand (it’s actually a huge balloon) we see it as though floating in space. In the Cathedral it filled the cleared nave, at once ethereal and admonitory, reminding us of what we could lose.

The path to the Cathedral led along the river embankment through Borough Market. What was once a wholesale food market has become – I can only call it a temple to Mammon. Huge crowds milled about, going nowhere, seeing nothing except vast facades of restaurants. Somewhere in there was still a market, but rather like the hidden self lurking behind the assumed faces and voices of Our Mutual Friend, it had lost its identity. Later in the day my friend and I fought our way through Soho and Chinatown, neon lights blazing, the same milling crowds. The thing that once was there, the real place, had been buried under an idea of itself, an idea in people’s minds, for which money would be exchanged, but the desired thing, the thing that had once been, would not be given in return. Dickens would have well understood all this, and in a way it is what Our Mutual Friend is about. Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

Our final point of call was the Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery. As if in a sign across the centuries, in one of Van Gogh’s portraits, ‘L’Arlésienne’, a copy of Contes de Noel (Christmas Books) is depicted on the table, the title on the spine clearly delineated. Van Gogh’s love of Dickens probably dated from his arrival in London at the age of twenty in 1873, just three years after Dickens’ death. His letters make clear that what he most appreciated in Dickens’ novels was the concern with ordinary working-class people and life, a concern that would dominate his own painting. He frequented Whitechapel during his time in London, aware of the connection with Dickens.

My time in London, walking the very streets that Shakespeare, Spenser, Dickens, Van Gogh, T. S. Eliot, walked, looking on the very river from which they drew their inspiration, reminded me of what culture really is and means. Van Gogh wrote of his time there:

I have a rich life here, ‘having nothing and possessing everything’. Sometimes I start to believe I am slowly becoming a true cosmopolitan, that’s not a Dutch man, English man or French man but simply a man.

We can’t absolve Charles Dickens from being very much an English man. But his concern with the lives lived not even on the margins but below them is at the heart of Our Mutual Friend. He saw money and the corrupting desire for it most clearly in this novel; but he also saw corresponding poverty, and what it could do to people. Shouldering through Borough Market, Soho and Chinatown, traversing the embankments of the river (built in the 1850s and 60s to house the new sewers to carry waste away from the metropolis), seeing the monstrous monuments to late capitalism, I thought what brilliant subjects these would have made for Dickens. Our Mutual Friend is a novel for our times. Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

All of the Charles Dickens novels mentioned are published by Wordsworth Editions.

Dickensian is the new series of adaptations of three Dickens novels on BBC Radio Four. Our Mutual Friend had its first instalment on November 3rd; there are two subsequent episodes on consecutive Sundays.

For more on the dust mounds of Victorian London, see dickensourmutualfriend.wordpress.com and www.litterbins.co.uk

For Luke Jerram and Gaia installations, see my-earth.org

For Vincent van Gogh: Poets and Lovers, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk

Main image: Sorting a dust heap at a County Council Depot, London, c1850 (1903). Artist: Unknown. Credit: The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Illustration 1864 of Gaffer and Lizzie 1864 Credit: The History Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Cover design for the first monthly instalment of Our Mutual Friend with illustrations by Marcus Stone, dated May 1864. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: ‘Mr. Riah and Miss Wren at the Six Jolly Fellowship Porters’. Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Clock tower of Southwark Cathedral near London Bridge. Credit: Philip Pound / Alamy Stock Photo

Our edition of Our Mutual Friend can be found here

For more information on Dickens’ life and works, visit The Dickens Society

Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

Our Mutual Friend Radio 4

Books associated with this article