I am the eye with which the Universe, Beholds itself and knows itself divine

Mia Rocquemore reflects on time and nature in the poetry of Shelley

The most famous of Shelley’s poems describes the annihilating effects of time:

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

(Ozymandias, 12-14)

The sands of time, both literal and metaphorical, mean that not only is man’s life upon the earth fleeting, but so too is his memory. “We are as clouds” floating across the sky, and “time’s fleeting river” soon washes away any remnants. Although explored throughout Shelley’s corpus, the theme is given the most attention in Queen Mab, which he subtitled “a philosophical poem”. The two-and-a-half-thousand line composition tells the story of a fairy queen, the eponymous Mab, giving a tour through time and space to the detached soul of the sleeping Ianthe, who shares the name of Shelley’s recently-born daughter. Travelling through terrestrial and celestial realms, the fairy and the spirit together visit the past, present and future, and explore ideas about death, nature and love. Most plain of their observations is that “man as vice has made him now” is not cut out for eternity:

What is immortal there?

Grave of Shelley

Nothing – it stands to tell

A melancholy tale, to give

An awful warning: soon

Oblivion will steal silently

The remnant of its fame.

Monarchs and conquerors there

Proud o’er prostrate millions trod –

The earthquakes of the human race;

Like them, forgotten when the ruin

That marks their shock is past.

(Queen Mab, II 115-125)

Where is the fame

Which the vain-glorious mighty of the earth

Seek to eternise? Oh! the faintest sound

From time’s light footfall, the minutest wave

That swells the flood of ages, whelms in nothing

The unsubstantial bubble.

(Queen Mab, III 138-143)

The vice of humankind means that some memories are better forgotten. It is a good thing, when “the tales / Of this barbarian nation, which imposture / Recites till terror credits, are pursuing / Itself into forgetfulness” (II 159-161). Indeed, the civilisations and peoples witnessed during the course of the supernatural voyage leave one with the impression of man as monster. Through the voice of Queen Mab, Shelley isolates three reasons for this: religion, war and rule, embodied by the “priest, conqueror, or prince”. Famously (infamously in his day) an atheist of non-violent socialist persuasions, the poet saw organised religion, collective aggression and social inequality as the key obstacles between humanity and utopia. Whereas “the universe, / In nature’s silent eloquence, declares / That all fulfil the works of love and joy,… / the outcast man… fabricates / The sword which stabs his peace” (III 196-20), and “kings, priests, and statesmen, blast the human flower, / Even its tender bud: their influence darts / Like subtle poison through the bloodless veins / Of desolate society” (IV 105-107).

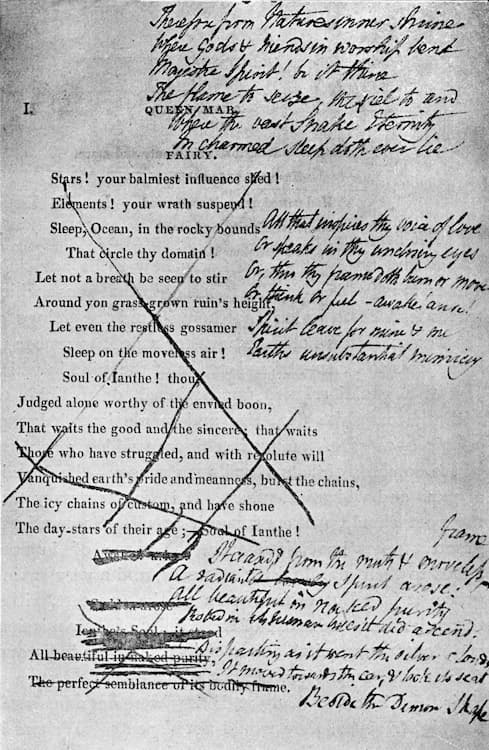

Excerpt from Queen Mab

And yet he optimistically envisages a day when mankind will no longer be blighted by these three plagues, when men will live in peaceful harmony with one another and, most importantly, with nature. “A brighter morn awaits the human day, / When every transfer of earth’s natural gifts / Shall be a commerce of good words and works” (V 251-253). Although by nature endowed with great gifts, both inherent and external, man has been corrupted by a number of vices: Eye of the Universe

Man is of soul and body, formed for deeds

Of high resolve, on fancy’s boldest wing

To soar unwearied, fearlessly to turn

The keenest pangs to peacefulness, and taste

The joys which mingled sense and spirit yield.

Or he is formed for abjectness and woe,

To grovel on the dunghill of his fears,

To shrink at every sound, to quench the flame

Of natural love in sensualism, to know

That hour as blest when on his worthless days

The frozen hand of death shall set its seal,

Yet fear the cure, though hating the disease.

(Queen Mab, IV 154-165)

Hence only by returning to a state of nature (“natural kindness”, “natural love”) can humanity resolve its woes (“unnatural pride”, “unnatural war”), as “from the soil / Shall spring all virtue, all delight, all love” (V 18-19). The fairy promises that “every heart contains perfection’s germ” (V 47), and insists that each one must be nourished and tended accordingly to bring it to bear perfection’s fruits. Such worship of nature as a salvific force exemplifies the Romantics’ adoration of the natural world. Alongside Coleridge, Keats and Wordsworth, Shelley harnesses its power to create sublime poetic imagery: Eye of the Universe

Evening came on,

The beams of sunset hung their rainbow hues

High ’mid the shifting domes of sheeted spray

That canopied his path o’er the waste deep;

Twilight, ascending slowly from the east,

Entwin’d in duskier wreaths her braided locks

O’er the fair front and radiant eyes of day;

Night followed, clad with stars

(Alastor, 333-340) Eye of the Universe

Although revered, nature is not always kind. It can be “rugged and dark”, filled with “fire and poison”, at once both “destroyer and preserver”; in Prometheus Unbound, the personified Earth declares that one can “find a grave or cradle in my bosom” (Act IV 348). Despite regular seasonal cycles, it is not always predictable. Shelley’s descriptions of the seasons are in fact often rather shocking: the winds of spring mock and destroy, summer can be “pallid”, instead of decline and decay “the children of the autumnal whirlwind” come to life, “leaves, whose decay…Rivals the pride of summer”, and in the place of stagnant chill hastens “wintry speed”. It is no wonder that man stands little chance of success when working against the forces of nature.

By contrast, however, when “he is made one with Nature: there is heard / His voice in all her music, from the moan / Of thunder, to the song of night’s sweet bird; / He is a presence to be felt and known / In darkness and in light” (Adonais, 370-374). By embracing the “Virtue, and Hope, and Love, [which] like light and Heaven, / Surround the world” (Laon and Cyntha, IX 3667-3668), one is no longer victim of time, “the king of the earth” whose ceaseless march tramples the legacy of kings, conquerors or clerics. Indeed, by discarding all those unnatural vices that man embodies at present, one can even throw off fear of death, and can “silently laugh at [his] own cenotaph / And out of the caverns of rain, Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb / … arise and unbuild it again” (The Cloud, 78-81). No longer a simple marker of death, “the grave…/ [will be] as a green and overarching bower / Lit by the gems of many a starry flower” (The Witch of Atlas, 597-600).

The man made one with nature can ford “time’s fleeting river”; the artist made one with nature gives birth to something greater: “Poesy’s unfailing River”. The immortality that Shelley saw in nature, he also found in “art, which cannot die” (Ode to Liberty, 133). The artist who accurately observes and appreciates nature, and is able to capture its majesty and transmit it in a compelling way, wins for his work something of its power and timelessness. When “the everlasting universe of things / Flows through the mind” of the poet (Mont Blanc, I 1-2), “truth’s deathless voice pauses among mankind!” (Laon and Cyntha, To Mary 118). In the Hymn of Apollo, Shelley uses the god of music and song to give voice to the importance of poetry:

I am the eye with which the Universe

Beholds itself and knows itself divine;

All harmony of instrument or verse,

All prophecy, all medicine are mine,

All light of art or nature; – to my song,

Victory and praise in its own right belong.

(Hymn of Apollo, 31-36) Eye of the Universe

A similar sentiment is expressed in Laon and Cyntha, with the young hero boasting that “all things became / Slaves to my holy and heroic verse, / Earth, sea and sky, the planets, life and fame / And fate, or whate’er else binds the world’s wondrous frame” (II 933-936). Shelley certainly seems to have thought that his own artistic work would long preserve his memory:

So I, a thing whom moralists call worm,

Sit spinning still round this decaying form,

From the fine threads of rare and subtle thought –

No net of words in garish colours wrought

To catch the idle buzzers of the day –

But a soft cell, where when that fades away,

Memory may clothe in wings my living name

And feed it with the asphodels of fame,

Which in those hearts which must remember me

Grow, making love an immortality.

(Letter to Maria Gisborne, 5-14) Eye of the Universe

Ozymandias, king of kings, had called the mighty to look on his works and despair, and yet many centuries later, all that remained of the tyrant were shattered ruins amid the “lone and level sands”. Shelley, a “poet of nature”, believed that mighty and lowly alike would look on the works of artists and through them be able to attain some connection to the great forces of nature that enable one to withstand the sweeping rush of time.

Our edition of Shelley’s works is here: Selected Poetry and Prose of Shelley

The Poetry Society’s piece on Shelley can be found here

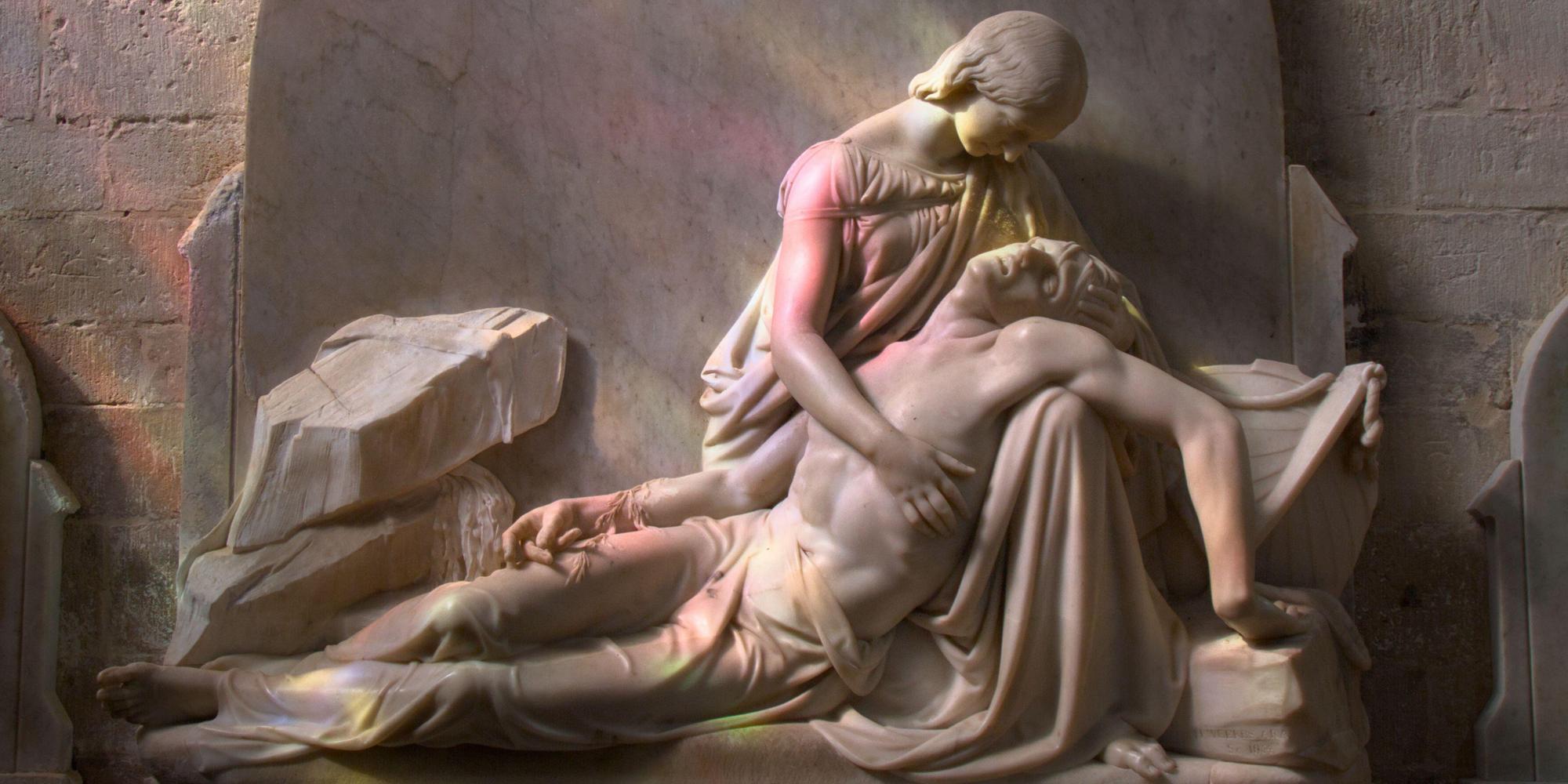

Main image: Marble statue By Henry Weekes of Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley, illuminated By stained glass window, 1854, Christchurch Priory, UK. Credit: LecartPhotos / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Grave of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Credit: Paolo Romiti / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Page excerpt from Queen Mab, published in 1813. Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo Eye of the Universe

Books associated with this article