‘Miss Austen’ – the BBC drama reviewed

‘She was the sun of my life, the gilder of every pleasure, the soother of every sorrow, I had not a thought concealed from her, and it is as if I had lost a part of myself’ (Cassandra Austen’s words about her sister Jane after Jane’s death) Miss

2025 marks the 250th anniversary year of Jane Austen’s birth. Sally Minogue looks at Miss Austen, BBC One’s first salvo in the celebrations.

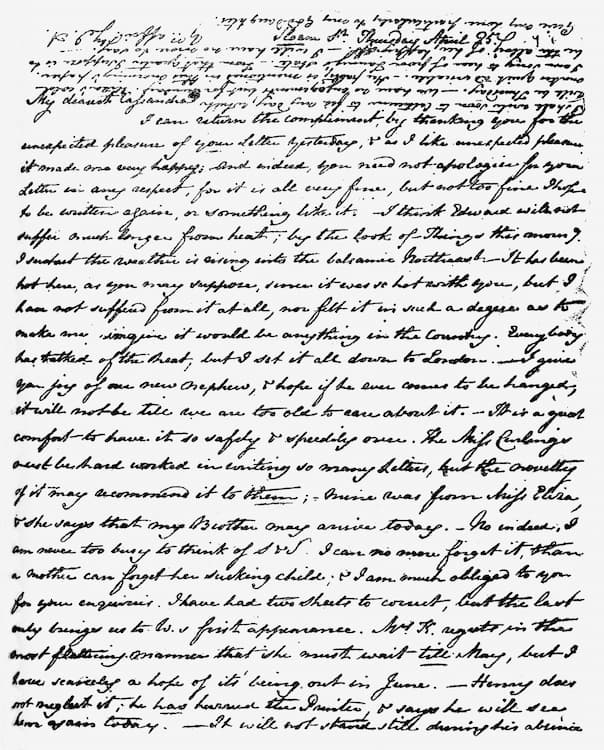

I have recently been sorting through many of my old letters, and my principal thought has been that I am very lucky to have been part of possibly the last generation to write, receive, keep and value personal letters. BBC One’s recent drama, Miss Austen, is built round the power of such letters, but here made much more resonant by the fact that these are the letters of Jane Austen. Not just personal, private letters then, but the letters of an iconic novelist, giving an insight into her inner self. We would expect such letters also to show the same insight, wit, verbal dexterity, and sometimes cruelty, that we find in her novels. An extra twist in this drama series is that Jane Austen herself is not its eponymous hero; the teasing title, Miss Austen, refers instead to her sister Cassandra. ‘Miss Austen’

Chawton House

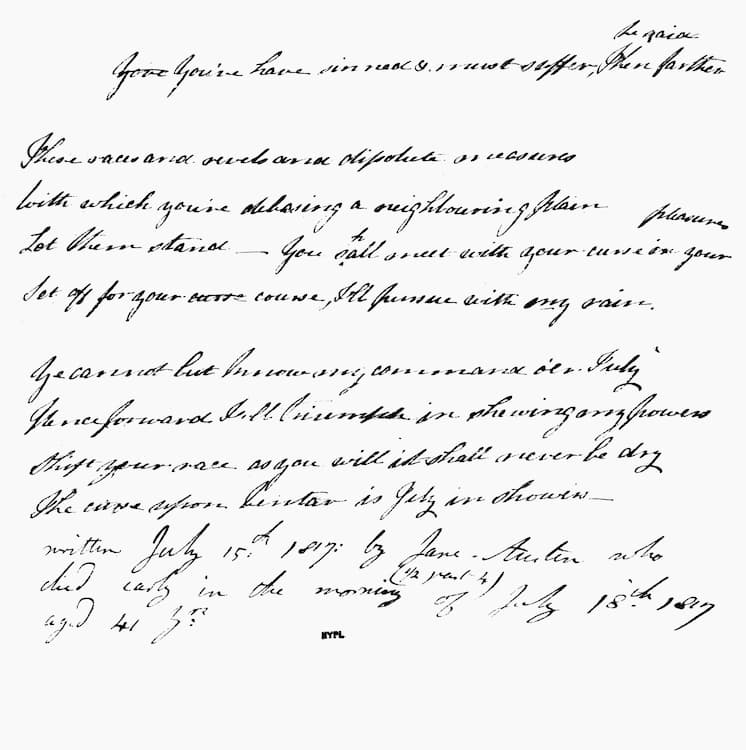

Cassandra and Jane were immensely close as sisters (Cassandra was the elder by three years) and Miss Austen shows this very touchingly through flashbacks to their young days together as well as their days growing older. Cassandra survived Jane by 28 years, dying at the age of 72 in 1845; Jane had died in 1817 at the young age of 41. The television drama shows us Cassandra in her later years, investigating and then destroying not her own correspondence with her sister, but Jane’s with Eliza, the wife of a family friend, Fulwar Fowle (who also happens to be the brother of Cassandra’s once-betrothed, Tom, who perished abroad).

Yet the real drama about Cassandra is that she destroyed most of her own personal correspondence with her sister Jane; they wrote to each other almost every day when apart. She also destroyed letters between Jane and others; but surely their intimate sisterly correspondence is the one we would most like to see. That of course may be the reason she destroyed them. We know only from her niece Caroline that ‘she looked over and burnt the greater part (as she told me), 2 or 3 years before her own death’.[1]

Miss Austen eschews the real drama of Cassandra’s letter-burning (that of the letters between her and her sister), concentrating instead on a supposed correspondence with Eliza Fowle. A very gentle digging reveals that the ‘letters’ to Eliza are non-existent; or at least if they did ever exist – and were possibly among those eventually destroyed by Cassandra – we do not know what they contained. The novel on which Miss Austen is based, by Gill Hornby, has a clear disclaimer at the end. All of the letters in the novel (and so in the tv series) are made up by the author, Gill Hornby, because of course as the ‘originals’ were destroyed, we cannot know what they contained.

A further fiction in the tv series (derived from the same fiction in Hornby’s novel) is that Cassandra, after the death of her fiancé Tom Fowle, had a later flirtation with and offer of marriage from one Henry Hobday. Now the drama of Cassandra’s burning of the letters revolves round a letter of Jane’s criticizing her, Cassandra, for not seizing the opportunity of love with Hobday. Hobday is a complete invention, as are Jane’s letters criticizing Cassie. Are not audiences of this drama being deceived, if they are led to think that Cassandra’s motives were of personal pique?

It is a mystery as to why Cassandra decided, near the end of her life, to destroy her sister’s letters, both to her and others, apart from the anodyne ones she distributed amongst her family as mementoes. Speculation is that these letters would have been seized upon to mar or muddy Jane Austen’s reputation, as it began to be vied for. The most likely explanation is that Cassandra felt the letters between the two were simply too private; why should anyone else see them? The oddity about the BBC One series is its focus not on their very intimate correspondence, but on an outlying one, and about an event – the possible marriage of Cassie – that was likewise imaginary. Miss Austen

It is a mystery as to why Cassandra decided, near the end of her life, to destroy her sister’s letters, both to her and others, apart from the anodyne ones she distributed amongst her family as mementoes. Speculation is that these letters would have been seized upon to mar or muddy Jane Austen’s reputation, as it began to be vied for. The most likely explanation is that Cassandra felt the letters between the two were simply too private; why should anyone else see them? The oddity about the BBC One series is its focus not on their very intimate correspondence, but on an outlying one, and about an event – the possible marriage of Cassie – that was likewise imaginary. Miss Austen

In these days of fan fiction, there’s no point objecting to whatever spins are put on the works and the lives of our great authors. Looked at in one way, these offshoots show that those authors and their works still live and breathe, and inspire new readers. That is all to the good. But Miss Austen and works of that ilk raise particular problems. Perhaps the greatest of these is that viewers are completely innocent of what is based on fact and what is not. There will be viewers of Miss Austen who will go away with the entirely misplaced idea that Cassandra burnt her sister Jane’s letters because Jane criticized her in a letter to a third party about her decision not to marry Henry Hobday. Henry Hobday – who did not exist!

But, to be fair, let’s think of the counter-argument. What this series set out to do was to dramatise the reasons for Cassandra’s burning the letters of her sister Jane. In this respect I think the drama does its job, since it gives us the emotional understanding behind Cassandra’s act. The specifics of the circumstances are not accurate, since they centre on Cassandra’s own hurt, at being misjudged by Jane. None of that is true. But what is caught is that sense of needing to destroy the past. It may be hurtful; it may be too accurate; it may be hurtful because too accurate. It may also be intensely private, and not to be shared with others. It may reveal something we’d rather not be revealed, about ourselves, or about the other. There is no doubt of the power and happiness of Cassandra’s relationship with her sister Jane, and her motives for destroying so many of her letters must have derived essentially from that.

Jane Austen herself knew the power of the letter as a means of deferred communication. Letters figure in several of her novels, and the short (and most think uncharacteristic) novel Lady Susan is her only epistolary novel. But I think of Persuasion, where letters figure in a way that is significant both to the plot and to the expression of emotion. Mrs Smith, producing a letter from amongst her husband’s papers to show Anne Elliot something of her background, avers :

Jane Austen herself knew the power of the letter as a means of deferred communication. Letters figure in several of her novels, and the short (and most think uncharacteristic) novel Lady Susan is her only epistolary novel. But I think of Persuasion, where letters figure in a way that is significant both to the plot and to the expression of emotion. Mrs Smith, producing a letter from amongst her husband’s papers to show Anne Elliot something of her background, avers :

The letter I am looking for was one written by Mr Elliot to him [Mr Smith] before our marriage, and happened to be saved; why, one can hardly imagine. But he [Mr Smith] was careless and immethodical, like other men, about those things; and when I came to examine his papers, I found it with others still more trivial from different people scattered here and there, while many letters and memorandums of real importance had been destroyed. Here it is. I would not burn it, because being even then very little satisfied with Mr Elliot, I was determined to preserve every document of former intimacy.

This is a superb description of the way such personal documents are ‘scattered’ without regard to significance. Meanwhile Anne, on reading the letter, thinks ‘that her seeing the letter was a violation of the laws of honour, that no one ought to be judged or known by such testimonies, that no private correspondence could bear the eye of others’. As so often, Austen has a complete and complex understanding, seeing both the importance of the letter in what it reveals to Anne, but also her sense of being privy to something she should not have seen. Miss Austen

Later in the novel, a letter is to be of far greater importance. As Anne Elliot’s former, rejected, but now longed-for love Captain Wentworth eavesdrops, Anne speaks feelingly of ‘loving longest, when existence or when hope is gone’. Wentworth writes a letter to her, alongside her speaking:

I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone forever.

The full letter is as full-blooded a confession of love as could be wished for. But it is in the second-hand form of a letter, which we read only as Anne herself does, and whose emotion we feel as she does. How much more powerful this is than a direct declaration, in a novel of constantly deferred possibilities.

The full letter is as full-blooded a confession of love as could be wished for. But it is in the second-hand form of a letter, which we read only as Anne herself does, and whose emotion we feel as she does. How much more powerful this is than a direct declaration, in a novel of constantly deferred possibilities.

Imagine the older Anne looking at such a letter after the death of Wentworth. Would she have kept it? Or would she have thought it should be kept private, known only to herself? That was Cassandra’s dilemma, but in her case complicated by the fact that her beloved sister Jane was on the way to becoming a great novelist. Sadly, Miss Austen doesn’t face up to the real private drama behind Cassandra’s burning of the letters. But burn them she did. And burning is a dramatic but certain form of destruction. Miss Austen

Thomas Hardy burnt many of his personal letters, intent on creating a particular portrait of himself for later eyes. But in his poem ‘The Photograph’ he captures what is involved in burning a personal document; it is a process in time when the act of destruction is played out before you:

The flame crept up the portrait line by line

As it lay on the coals in the silence of night’s profound,

And over the arm’s incline,

And along the marge of the silkwork superfine,

And gnawed at the delicate bosom’s defenceless round.

Then I vented a cry of hurt and averted my eyes;

The spectacle was one that I could not bear,

To my deep and sad surprise;

But compelled to heed, I again looked furtive-wise

Till the flame had eaten her breasts, and mouth, and hair.

Enough to send a shudder; but Hardy has it right. Burning a letter, like burning a photograph, feels like burning the person in some way. That of course is the point.

Miss Austen missed an opportunity, but did at least get that one thing right: the distress and complexity of addressing the past, especially in the form of personal letters in a person’s handwriting – itself redolent of the person who wrote it, their very hand. And if letters can be burnt, they must first be written. In Persuasion, Captain Wentworth’s letter reverses the past – the best sort of destruction. ‘Miss Austen’

All of Jane Austen’s novels are published by Wordsworth Editions.

Thomas Hardy: The Collected Poems, Wordsworth Editions

Claire Tomalin, Jane Austen: A Life, Penguin Books

Gill Hornby, Miss Austen, Penguin Books.

[1] Documented in Claire Tomalin, Jane Austen, Penguin Books, 1998

Main Image: Cassy Austen (SYNNOVE KARLSEN), Jane Austen (PATSY FERRAN), Cassandra Austen (KEELEY HAWES) and Isabella (ROSE LESLIE) in the BBC production of Miss Austen

Credit: BBC/Bonnie Productions/MASTERPIECE/Robert Viglasky Photographer: Robert Viglasky Image copyright: Bonnie Productions

Image 1 above: Jane Austen’s home Chawton Manor Credit: MIKE WALKER / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Letter from Jane Austen to Cassandra Austen. Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Credit as per Main Image

Image 4 above: Letter from Jane Austen written three days before her death on 18 July 1817. Credit: GRANGER – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Our extensive selection of Jane Austen’s works in paperback, multiple hardback forms and a box set with prices ranging from £3.99 to £30 can be found here: The Wordsworth Jane Austen editions

For more information about Jane Austen’s life and works visit The Jane Austen Society UK