The Ghost Man

Stephen Carver looks at the works of Algernon Blackwood

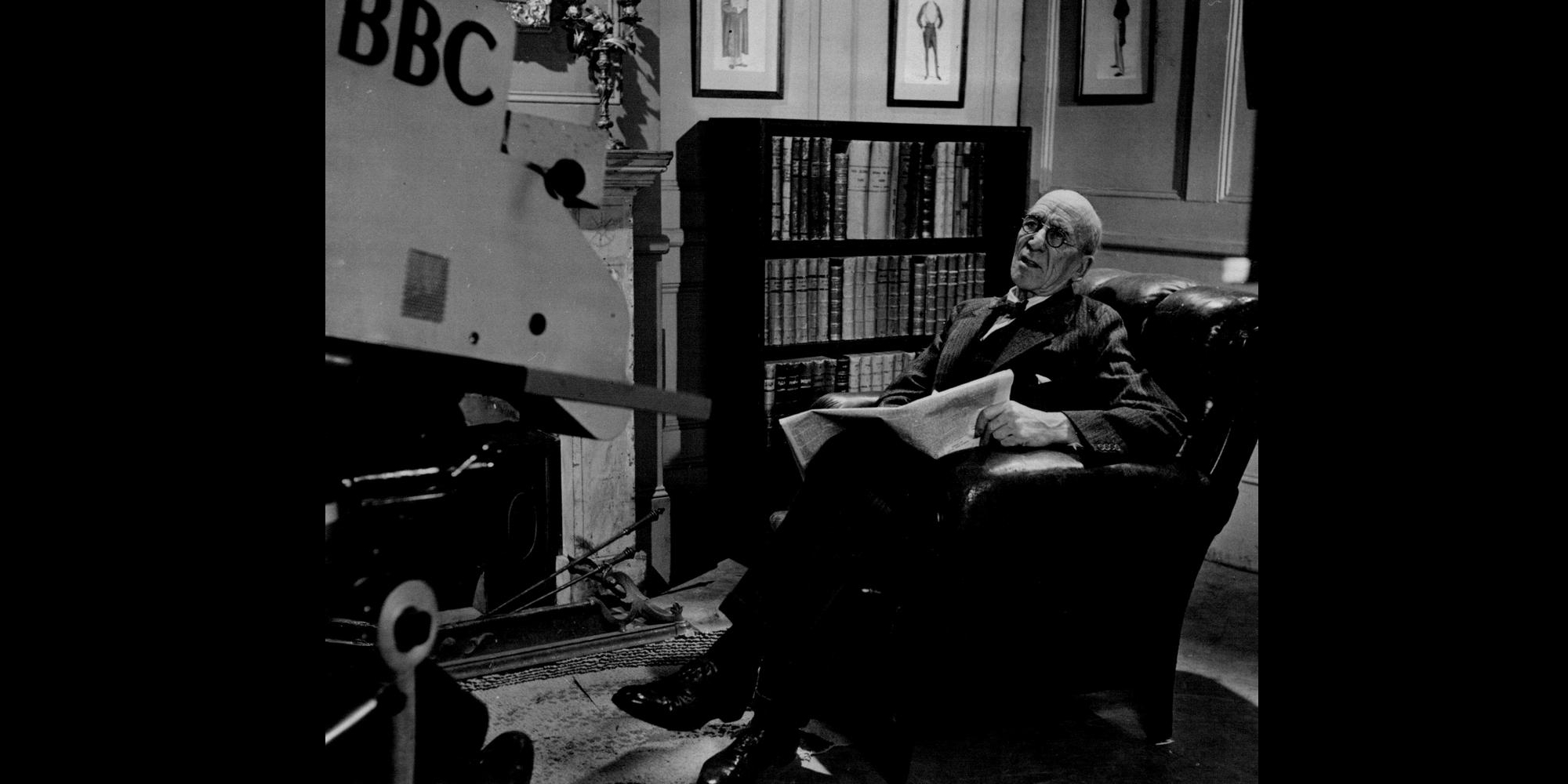

On Halloween night 1947, British television viewers were mesmerised by the storytelling powers of Algernon Blackwood, then 78 years old. It was a simple format, the author sitting in an easy chair by a fireplace, just talking, a man in the chimney corner delivering a tale. His long, lined face, weather-beaten and ancient, was that of the true adventurer, a man who had travelled to the lost, lonely places, and returned possessed of arcane knowledge. The BBC make-up girls had learned to leave it alone, only dusting his bald head to stop it reflecting the studio lights. His eyes, though, still had the wonder of a child, sparkling with mischievous imagination, stripping the years away. And as he gazed past the camera and into your home, his voice sonorous yet amiably conversational, you knew he was speaking directly to you. The Ghost Man

It was one of his ‘higher space’ anecdotes – exploring his theory of ‘another dimension at right angles to the three we know’ – not a published story, but told a hundred times in a hundred different ways at a hundred social gatherings. As a curate and a stockbroker go for a walk together, the curate is disturbed by a disembodied voice calling, ‘Come with me…’ His companion seems unaware of it. At the end of the story, the curate looks around, still searching for the source of the voice, and when he turns back the stockbroker has vanished. Blackwood leaned slowly forward as he ended his story, then he, too, disappeared, fading away on screen to leave only his empty chair.

The BBC switchboard was jammed, and the next morning the newspapers were full of it. There would be nothing like it again until the BBC ran Stephen Volk’s Ghostwatch on Halloween in 1992, a fake live broadcast of a paranormal investigation gone wrong presented by Michael Parkinson that traumatised a generation. And what is nowadays a simple special effect was technology indistinguishable from magic in 1947, especially on live television. The trick also seemed all the more real because Blackwood was at the heart of it. ‘The Ghost Man’ they called him in the press: mystic, paranormal investigator, and one of a highly select group of British authors designated by H.P. Lovecraft ‘Modern Masters of Horror.’

Regrettably, no recording exists, and though largely forgotten now ‘The Curate and the Stockbroker’ was a landmark in the history of early British television, and Algernon Blackwood was a post-war celebrity. He had been a fixture on BBC radio since 1934, mostly telling stories, and had also appeared on the first ever television broadcast in Britain on November 2, 1936. When he was awarded a CBE in 1948, it was for his services to broadcasting as much as literature, his radio stories raising public morale during and after the war. It was also a belated acknowledgement of his work during the First World War, when he was an agent for Military Intelligence in Switzerland and afterwards a Red Cross ‘Searcher’, helping relatives trace their lost loved ones. The following year, he won the Royal Television Society award for ‘Outstanding Television Personality of 1948’, a remarkable achievement for an elderly if dapper man in an increasingly complex visual medium who just sat on his own in a simple set and told stories. His presence and personality alone held TV audiences spellbound. The Ghost Man

And Blackwood had always been a natural storyteller. As he wrote of his time living in New York in his autobiography Episodes Before Thirty (1923):

I discovered this taste for spinning yarns, usually of a ghostly character, and found, to my surprise, that my listeners were enthralled. At a moment’s notice, no theme or idea being in my head, I found that I could invent a tale, with beginning, middle and climax. Something in me, doubtless, sought a natural outlet. The stories, at any rate, poured forth endlessly.

Blackwood wrote none of these down, but when he returned to his native England in 1899 he began to write almost compulsively, producing dozens of short, mostly supernatural stories, hardly any of which ever saw publication.

It was not until one of his New York friends, the journalist Angus Hamilton, visited Blackwood in London in 1906 that things changed. When he asked Blackwood if he’d done any writing, Blackwood showed him a cupboard full of typewritten manuscripts. Hamilton borrowed a pile and a few weeks later Blackwood was approached by the recently established publisher and former literary agent Eveleigh Nash, who wished to publish a collection of his stories, which Hamilton had shown him without Blackwood’s knowledge.

The result was The Empty House and Other Ghost Stories (1906), a fascinating preface to the huge body of work Blackwood would go on to produce over the next forty years or so. The allure and the threat of the wilderness is already prominent; there are paranormal investigations, mirroring his own experience in the field, eerie ghost stories, a couple of murder mysteries, and even a hint of a werewolf. The style is vivid and full of personality, conveying a sense of authenticity that is further supported by the anecdotal delivery. Blackwood the psychic investigator was either present, we feel, or received the information first-hand from someone who was. The Ghost Man

The Wendigo and Other Weird Tales

Following in the wake of the golden age of the Victorian ghost story, Blackwood was at the forefront of a new generation reforming and refining literary horror, Lovecraft’s other ‘Modern Masters’: Arthur Machen, M.R. James, and Blackwood’s close friend Lord Dunsany. This was also the time of the esoteric society, of middle-class metaphysics and occultism. The atmosphere of pre-war Britain was heavy with ceremonial magic, astrology, Tarot, geomancy, alchemy, paranormal research, secret doctrines and magical wars. Blackwood was at various times a Theosophist, a member of the Ghost Club and the Society for Psychical Research, and was introduced into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn by W.B. Yeats. Here he met Arthur Machen, ultimately reaching the Inner Order grade of ‘Adeptus Minor’ in 1915.

Reviews were encouraging. ‘Persons of weak nerves would do well not to read the stories in “The Empty House” just before going to bed,’ advised The Bookman, ‘there is a brood of weird and grisly nightmares in each one of them.’ The review also commended Blackwood’s realism. Similarly, The Academy review evoked gothic royalty, suggesting Blackwood ‘is to be congratulated on having produced one of the best books of “horror” since the appearance of Mr. Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”.’ Hilaire Belloc in The Morning Post, meanwhile, saw the modern ghost story as a very English phenomenon in his review, describing Blackwood as ‘instinct with this national power.’

The Listener and Other Stories followed in 1907, already signalling a growing technical sophistication. The title story shows Blackwood moving away from the conventional ghost story, instead concentrating on the mind of the victim of the haunting, while ‘The Woman’s Ghost Story’ explores the psychology of the ghost, both radical digressions from the norms of the genre. ‘The Insanity of Jones’ is the first of many stories Blackwood wrote about reincarnation, in which he deeply believed almost to the end of his life. The intense ‘Max Hensig – Bacteriologist and Murderer’ draws heavily on Blackwood’s time as a court reporter for the New York Evening Sun. Blackwood had interviewed many high-profile defendants, including Lizzie Borden. Though Borden was acquitted of the axe murders of her father and stepmother, Blackwood had been in no doubt about her guilt. In ‘Max Hensig’, a court reporter learns the horror of the condemned when he finds himself stalked by a similarly acquitted psychopath. Again, the authenticity of experience brings the suspense to life on the page. Most notably of all, this collection contains ‘The Willows’, considered by many, including H.P. Lovecraft, to be Blackwood’s finest story, rivalled only by ‘The Wendigo’, his most famous story of all. The Ghost Man

‘The Willows’ was inspired by one of Blackwood’s ‘vagabond holidays’, long and potentially dangerous excursions into the wild places of the world. In this case, he and Wilfred Wilson (a gentleman of leisure from a wealthy banking family) canoed along the Danube from the Black Forest to Budapest. As Blackwood wrote of the journey for MacMillan’s Magazine: ‘The loneliness and desolation of these vast reaches of turbulent river and low willow-clad islands were impressive; in flood time it must be grand.’ In the subsequent story, an unnamed narrator and his companion make camp on one such sandy, ‘willow-clad’ and rapidly disintegrating island. In different ways, they become aware that something ineffable does not want them there:

The sense of remoteness from the world of humankind, the utter isolation, the fascination of this singular world of willows, winds, and waters, instantly laid its spell upon us both, so that we allowed laughingly to one another that we ought by rights to have held some special kind of passport to admit us, and that we had, somewhat audaciously, come without asking leave into a separate little kingdom of wonder and magic—a kingdom that was reserved for the use of others who had a right to it…The Ghost Man

Blackwood artfully blends this sense of foreboding with the awe due to the untamed natural world, as each man succumbs emotionally to the isolated environment that will not, apparently, let them leave. In an example of what Lovecraft would later characterise as the ‘literature of cosmic fear’, the remote location seems to be a frayed frontier between our world and another which is never truly defined, making it all the more alien and terrible.

Blackwood raised the bar again the following year with John Silence – Physician Extraordinary. Although not a novel, and built out of a mix of old and new stories based around a unifying character, this was Blackwood’s first attempt at a sustained narrative and represents further literary development. Dr. John Silence is introduced as a man of power, some sort of Magus, although his affiliations are never made clear. He is described simply as a ‘Psychic Doctor’ who takes on cases without charge that interest him and in which he thinks he can be of service:

In order to grapple with cases of this peculiar kind, he had submitted himself to a long and severe training, at once physical, mental, and spiritual. What precisely this training had been, or where undergone, no one seemed to know,—for he never spoke of it…The Ghost Man

What we do know is that this training ‘involved a total disappearance from the world for five years.’ In the three stories in which he is an active participant, he helps a writer who has inadvertently unleashed a malevolent presence after experimenting with hashish (something Blackwood alludes to doing in New York in his autobiography); tackles a fire elemental guarding an Egyptian mummy; and deals with a case of psychic lycanthropy. Like Sherlock Holmes, Silence is always thinking ten moves ahead, and likes testing his bemused companions to see if they’ve figured out what’s going on, before delivering a pseudo-scientific, quasi-mystical summary at the end of each story.

John Silence heralds a generation of fictional occult detectives, predating characters like William Hope Hodgson’s ‘Thomas Carnacki’ (a character encouraged by Nash after Blackwood lost interest in John Silence), Sax Rohmer’s ‘Moris Klaw’, and Aleister Crowley’s ‘Simon Iff’, the stuff of Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. The archetype can still be seen today in figures like ‘John Constantine’ and ‘Fox Mulder’, all of whom really flow from the template left by John Silence: a character with an authentic background through his creator’s own experience of paranormal investigation and the pursuit of esoteric knowledge. Most authors rely on research and imagination, but Blackwood had lived these things, and knew men not unlike John Silence, such as the unnamed fourth-year medical student and ‘very gifted and unusual being’ at Edinburgh University whom Blackwood cites as an influence on his ‘Psychic Doctor’ in his autobiography. John Silence is also cryptically dedicated:

To

M.L.W.

The Original John Silence

and

My Companion in Many Adventures

To whom this refers remains a mystery, as do the adventures. Blackwood deliberately excludes this side of his life from Episodes Before Thirty, which tantalisingly closes: ‘Of mystical, psychic, or so-called “occult” experiences, I have purposely said nothing, since these notes have sought to recapture surface adventures only.’ As another autobiography concerning ‘Episodes After Thirty’ was never written, we must take his fictional output, which also began after thirty, as the closest we will get to that second memoir. The Ghost ManThe Ghost Man

John Silence was a bestseller, allowing Blackwood to quit his dreary day job to focus on writing and his passion for travel. As he joyously wrote in his autobiography, ‘with typewriter and kit-bag’ he was able to ‘take my precious new liberty out to the Jura Mountains where I lived in reasonable comfort and wrote more books.’ And this is pretty much what he spent the rest of his life doing; travelling, staying with friends, never settling, never marrying, eschewing any personal possessions he couldn’t easily carry, and writing.

To not just succeed but to excel at something must have come as quite a surprise. Blackwood’s life up this point had been characterised by failure, hardship, and downright disaster, not the usual path one would expect of someone whose family is listed in Burke’s Peerage. Blackwood was the third of the five children of Stevenson Arthur Blackwood, then Clerk to the Treasury, and Harriet Dobbs, the widow of the 6th Duke of Manchester. He grew up in a strict evangelical household, but quietly rebelled when he read a Theosophist translation of The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali left by a visitor writing a tract about Satan disseminating dangerous Eastern philosophy. As a young man, Blackwood was passionate about Nature, and was happiest throughout his life travelling to wild, deserted places like the great primordial forests of North America, the deserts of Egypt, and the Swiss Alps – all of which served as settings in many of his stories.

Blackwood attended Wellington College in Berkshire. He disliked the strict discipline and rote learning, and did not perform well academically. In a desperate corrective move, his father sent him to a Moravian Brotherhood school in the Black Forest in 1885. The monastic ascetism and regular exercise appealed to Blackwood, as did the countryside. That said, he does use it as the setting for the John Silence story ‘Secret Worship’, which depicts the schoolmasters as Satanists. Blackwood was next sent to Bôle in Switzerland to learn French. The Ghost Man The Ghost Man

For a pious man, Arthur was oddly interested in the growing field of parapsychology, though like many Christians he loathed Spiritualism. Coincidently, he worked with Frank Podmore, an influential member of the recently founded Society for Psychical Research. Though Arthur never formally joined the SPR, he was a keen supporter, particularly when it came to debunking Spiritualism. His son was also interested, and Arthur allowed him to join the SPR, and to accompany Podmore and the psychologist Edmund Gurney on investigations. His first recorded case was a haunted lodging house in Kensington, and several of these experiences found their way into his fiction. Throughout his life, Blackwood never stopped hunting ghosts. As he advised in the surviving BBC radio story ‘Pistol Against a Ghost’: ‘If you do have the luck to see an apparition and it scares you, your best weapon is keen observation and a good healthy scepticism.’ You can tell in his voice that he’s speaking from experience.

In preparation for a planned career farming in British Columbia, Blackwood went up to Edinburgh University in the autumn of 1888 to formally study Agriculture and Rural Economy, but left after a year, having spent most of his time focused on Theosophy and the SPR. In 1890, he went to Canada to seek his fortune anyway, but lost his entire inheritance after two disastrous business ventures in dairy farming and hotel management. After an idyllic summer spent idling on the shore of Lake Rosseau, he moved to New York in 1892, working as a low-paid court reporter for the Evening Sun, eventually becoming homeless and briefly addicted to morphine. Having failed to get rich during the Ontario gold rush, Blackwood became a staff reporter for the New York Times and then private secretary to the banker James Speyer. This is the period Blackwood covers in Episodes Before Thirty, a candid memoir of defeat after defeat followed by impending defeat.

Coming home unlocked something in Blackwood, and his literary output was prodigious. In his long life, Blackwood wrote thirteen novels and twelve collections of short stories, as well as seven plays, ten children’s books, his autobiography, and numerous short articles, TV and radio talks. He remained active to the end, mostly focused on radio in his final years. His last short story collection, The Doll and One Other, was published by August Derleth’s Arkham House in 1946, with one further story appearing in Weird Tales in 1948. He died of a stroke at his flat in Kensington aged 82, and his ashes were scattered at the Saanenmöser Pass in the Swiss Alps. The pace of culture being what it is, Blackwood’s stellar reputation did not survive him. Though his work has been explored by a handful of literary critics, it is inexplicably largely overlooked by the academy and the wider horror community, with little of his writing filmed or currently in print.

Blackwood wrote across several overlapping genres, but predominantly, his fiction fell into three categories: children’s stories, ecofiction (before the label existed), and, most of all, horror. He was fascinated by the psychology of fear, and his stories are often deep dives into the psyches of the haunted, the mad, and the cursed. All of Blackwood’s fiction is structured around a unifying belief that ‘everywhere in Nature there was psychic energy,’ a similar theory to that of German scientist and philosopher Gustav Fechner (1801 – 1887). In synthesising Christianity and Paganism, Fechner viewed the universe as inwardly alive and consciously animated, a position Blackwood had similarly arrived at as a young man in tune with the natural world and active in esoteric circles. Throughout his life, Blackwood experimented in ‘expanding consciousness’ to access ‘the great spiritual forces that I believed lay behind all phenomena,’ and his stories validate and propagate this worldview. The experience can be visionary and awe-inspiring, but in his horror fiction life-threatening and terrifying. It is the nature of the interaction that determines the nature of the story. The animistic universe remains vast, unchanged and disinterested. As the divinity student ‘Simpson’ comes to realise in ‘The Wendigo’: ‘The beauty of the scene was strangely uplifting … Yet, ever at the back of his thoughts, lay that other aspect of the wilderness: the indifference to human life, the merciless spirit of desolation which took no note of man.’ So the elemental forces in ‘The Willows’, for example, the haunted houses, and the legendary Wendigo are not in themselves hostile, but if disturbed by human beings their response is powerful, unpredictable, frightening and dangerous. In many of Blackwood’s stories, the catalyst is invasion by man, into the wilderness, into the haunted space, and often all that can save them is their very insignificance. As the ‘Swede’ in ‘The Willows’ tells his companion: ‘There are forces close here that could kill a herd of elephants in a second as easily as you or I could squash a fly. Our only chance is to keep perfectly still. Our insignificance perhaps may save us.’The Ghost Man

Reprints and rearrangements aside, there were twelve original short story collections published in Blackwood’s lifetime, all containing ‘weird’ tales comprising about a million words in total. Choosing a selection of his horror writing for a single volume has thus been a challenging but rewarding task. In seeking to provide a thorough and representative Blackwood ‘Reader’, our new Blackwood collection The Wendigo and Other Weird Tales includes a range of stories published between 1899 and 1946 offering the best of all the different flavours of Blackwood’s weird fiction: supernatural, occult, psychometric, reincarnation, elemental, doppelgänger, ‘higher space’, and timeslip, including his most famous stories, a few surprises, and a decent dash of John Silence. View this collection as a ‘Sampler’, and a springboard from which to seek out Blackwood’s other stories and novels, all of which have something to recommend them, and deserve much more attention than they presently receive. It is strange to think that when Blackwood died in 1951 he was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, a household name, and a National Treasure. In my opinion, his strange, haunting and highly original fiction is more than ripe for a revival. Perhaps we can start that here.The Ghost Man

Main image: Blackwood appearing in the television series “Saturday-Night Story”. January 24, 1948. (Photo by BBC). Credit: SuperStock / Alamy Stock Photo

Image above: Our new collection of Blackwood’s works – more details here

Another piece on Blackwood can be found here: WFR’s 101 Weird Writers #19 — Algernon Blackwood | Weird Fiction Review The Ghost Man

Books associated with this article