David Stuart Davies looks at Agnes Grey

Agnes Grey was Anne’s Brontë’s first novel, written at the time when her sister Emily was working on Wuthering Heights and sister Charlotte on The Professor. David Stuart Davies takes up the story.

‘The statistics touching lunatic asylums give a frightful proportion of governesses in the list of the insane.’ – Fraser’s literary magazine, 1844

Anne Brontë (1820-1849)

Anne Brontë (1820 -1849) was the youngest and perhaps the least well known of the Brontë sisters, those brilliant northern scribes who created some of the most enduring of novels written in the first half of the nineteenth century. Agnes Grey was Anne’s first novel, written at the time when Emily was working on Wuthering Heights and Charlotte on The Professor. In 1846 their three narratives were ready to be sent off to publishers in London.

Emily’s novel attracted the larger share of critical attention in the form of astonishment, perplexity and outrage. By contrast reviewers observed that Agnes Grey was ‘less ambitious and less repulsive.’ Although written before Charlotte’s Jane Eyre, Agnes Grey was published afterwards and as a result fell under the shadow of her sister’s book and thus fared less well.

However, George Moore, the respected Irish novelist, regarded it as, ‘The most perfect prose narrative in English letters… a narrative simple and beautiful as a muslin dress… We know we are reading a masterpiece. Nothing short of genius could have set them before us so plainly and yet with restraint.’

What Anne’s novel lacks in sensationalism was made up with a fierce obsessional realism. The story provides a penetrating insight into the mid-nineteenth century world of the governess – those educated women employed to educate and control the offspring of wealthy parents. Their standing in the household and society was a peculiar, isolated state – neither family nor servant. With relentless accuracy the novel charts the dilemmas and torments that made up a governess’s life at this time. The verisimilitude of the drama is enhanced by the fact that it was drawn from Anne’s own experiences, having served as a governess in two separate households. She was possessed with an urgent need to inform her contemporaries about the desperate position of unmarried, educated women in the male dominated society who were driven to take up the only ‘respectable’ career open to them in order to earn a living.

Nick Holland observed that in writing a biography of Anne Brontë, he found in Agnes Grey ‘sixty instances that could be directly related to incidents in Anne’s own life.’ The first clue is in the opening page: ‘My father was a clergyman in the North of England…’ – as was Anne’s father. Further comparisons between Anne and her fictional heroine follow.

Set out in a first-person narrative, Anne Brontë describes the almost intolerable pressures that a governess’s life involved – the isolation, away from all friends and family, the frustrations of dealing with her recalcitrant charges, the insensitive and sometimes actively cruel treatment on the part of her employers and their family. Additionally, the author depicts scenes of cruelty to animals, as well as the degrading treatment of Agnes, illustrating the oppression of these two groups, animals and females – that are regarded as ‘beneath’ the upper-class human male and can be treated as casually as their whims take them.

Over the course of the novel Agnes serves time with two families: the Bloomfields and the Murrays. The Bloomfield children are frightful creatures, so spoiled and nastily disobedient that Agnes has to resort to physical restraints to control them. The Murray children are older but just as challenging; one sister is preening, manipulative and self-idolising, while the other adopts rough tomboy ways and cursing like a stableboy. In all these traumas, Agnes’ employers fail to have any regard for her. To them she is invisible. The novel’s subtle suppressed anger is an eye-opening window on the injustices suffered by women in the mid nineteenth century. It was a theme she was to develop most dramatically in her second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

Of course, as is typical in Victorian fiction, an element of gentle romance is introduced into the plot of Agnes Grey. This comes in the form of Mr Weston. He is not a fiery tempestuous figure like Wuthering Heights’ Heathcliff nor Mr Rochester from Jane Eyre, but a kindly, sympathetic curate who regards Agnes not as a down-trodden governess but as a woman. He emerges as a realistic character and his presence eases her distress and we are gradually led to a happy ending.

However, despite the emotional resolution of the plot, the issues raised by the treatment of Agnes as a woman and her perception by her employers as someone whose standing in society and her feelings are of little consequence have resonances through the ages and no less so than now in the 21st century when women’s rights are still challenged and, in many cases, ignored. As such, then, Agnes Grey like most works of great literature, has much modern relevance.

There was a BBC radio adaptation in 1997 and a number of audio book versions are available, but surprisingly, there has never been a film or television version of the novel. It is not clear why no one has attempted to bring Agnes Grey to the cinema or television screens. The reason for this may be because of the episodic structure and observational nature of the narrative, with a lack of major conflict and dramatic events presented in the novel. However, because of the issues raised in the book regarding the treatment of women and their rights, perhaps now is the time for some enterprising producer/writer to grasp this intriguing nettle and bring us a fully realized screen adaptation of this most fascinating of novels. In the meantime, there is the subtle and perceptive prose of the original narrative to engage and divert us.

Main image: Light winter snow, Haworth Parsonage, Yorkshire. Credit: David Thompson / Alamy Stock Photo

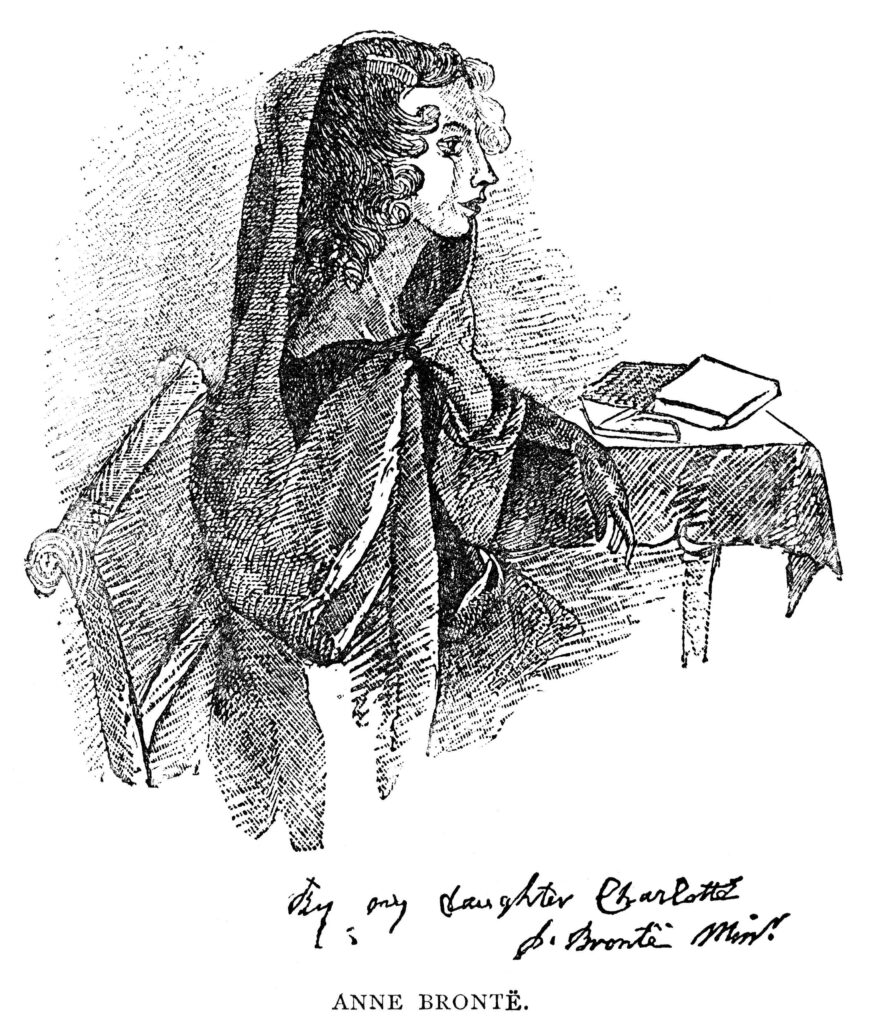

Image in text: Anne Brontë. Line engraving after a drawing by her sister Charlotte, including a handwritten notation at bottom by their father, Patrick. Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article