‘Avay vith melincholly’: The Story Behind ‘The Pickwick Papers’

Stephen Carver rediscovers the pleasures of reading Dickens’ first novel. The Pickwick Papers

Dickens had only just celebrated his 24th birthday when the publisher Willian Hall paid a call on him at his lodgings in Furnival’s Inn to offer him a writing contract. It was early February, 1836, and Dickens’ collected Sketches by ‘Boz’ had literally just been published in book form by John Macrone. These sketches ‘Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People’ had been published individually in several popular newspapers over the previous four years, but Macrone’s book represented a professional breakthrough. Dickens had been socially adopted by some heavy hitters in literary London, like the author of the bestselling Rookwood, William Harrison Ainsworth, his partner in crime the illustrator George Cruikshank, and the Examiner’s literary editor, John Forster. These contacts had brought Dickens to Macrone and thus to the collected Sketches, but for all that, he was still just an unknown with a bit of potential when Hall came calling. Hall was half of the relatively new firm of Chapman and Hall, a publisher and bookseller he had co-founded with his friend Edward Chapman in 1830. Chapman was a voracious reader with a good eye for talent while Hall had the business brain. The Pickwick Papers

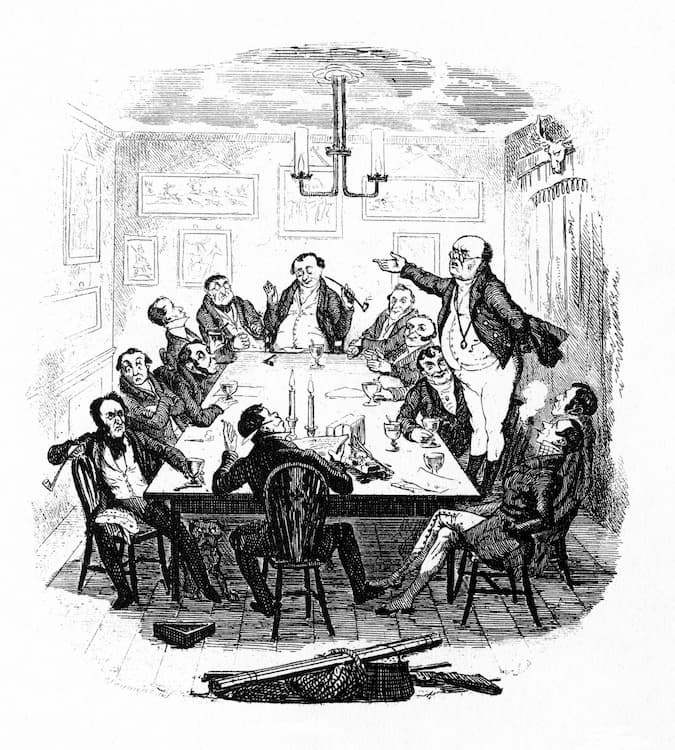

One of Robert Seymour’s illustrations for ‘The Pickwick Papers’

Chapman and Hall had had some success working with the illustrator and caricaturist Robert Seymour, an artist then rivalled only by Cruikshank. The Squib Annual of Poetry, Politics, and Personalities was a collection of comic verses written around twelve cartoons by Seymour. The artist was also independently publishing Sketches by Seymour, a series of humorous lithographs depicting inept sportsmen and comedic Cockneys huntin’, shootin’, and fishin’. Seymour had pitched the idea of a shilling monthly magazine to Chapman and Hall depicting the misadventures of a group of Cockney sportsmen known as the ‘Nimrod Club’. Cheap paper and advances in printing had created a new market for shilling magazines aimed at the growing urban middle and working classes. Gentlemen’s sporting clubs were a popular subject, and had been since the Regency publishing sensation Life in London, with illustrations by George and Robert Cruikshank and ‘letterpress’ by the sporting journalist Pierce Egan. As a well-known artist, Seymour’s illustrations would lead the project, to which an ’editor’ would append a few thousand words of text. Hall was offering the job to Dickens. Dickens knew nothing about sport, but as he was planning to marry, the money was too good to turn down at nine guineas per sheet (sixteen pages of printed text), one-and-a-half sheets per month – about 12,000 words. He wrote to his fiancée Catherine Hogarth, ‘the work will be no joke, but the emolument is too tempting to resist.’

Though fourteen years Seymour’s junior and hardly the ‘name’ in the project, Dickens quickly reversed the roles, arguing (as he later wrote in his preface to the cheap edition of 1847) that ‘it would be infinitely better for the plates to arise naturally out of the text; and that I should like to take my own way, with a freer range of English scenes and people, and was afraid I should ultimately do so in any case, whatever course I might prescribe for myself at starting.’ Dickens also told Hall that ‘the idea was not novel, and had already been much used.’ The sporting club was therefore dropped as the premise, although the character of Nathaniel Winkle was created as a concession to Seymour’s original plan, being a young man who fancies himself a sporting gentleman yet has no aptitude whatsoever and is downright dangerous when it comes to horses and guns. This must have been humiliating for Seymour, but he begrudgingly concurred. Thus did Dickens become the ‘editor’ of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. ‘Pickwick is at length begun in all his might and glory,’ he wrote to his publishers.

Dickens hit the ground running, and playing to his strengths as a journalist – ‘Boz’ the observer of London life and also the court reporter and parliamentary correspondent who had travelled around the south of England covering local elections. He even threw in favourite places from his childhood. The Pickwick Papers was to be the Sketches on a much grander scale, the mission statement plain in the first couple of pages of the opening chapter:

‘That the Corresponding Society of the Pickwick Club is therefore hereby constituted; and that Samuel Pickwick, Esq., G.C.M.P.C., Tracy Tupman, Esq., M.P.C., Augustus Snodgrass, Esq., M.P.C., and Nathaniel Winkle, Esq., M.P.C., are hereby nominated and appointed members of the same; and that they be requested to forward, from time to time, authenticated accounts of their journeys and investigations, of their observations of character and manners, and of the whole of their adventures, together with all tales and papers to which local scenery or associations may give rise, to the Pickwick Club, stationed in London.’

Samuel Pickwick, founder of the club which bears his name, is a warm-hearted if naïve retired businessman who fancies himself a philosopher though his insights are unremarkable: ‘There sat the man who had traced to their source the mighty ponds of Hampstead, and agitated the scientific world with his Theory of Tittlebats.’ Tracy Tupman is a middle-aged lothario who never makes a conquest; Augustus Snodgrass describes himself as a ‘poet’ but never writes anything; and Nathaniel Winkle is a sportsman of staggering inability. By the end of the first instalment, they are on the road and already in trouble.

Despite his reputation, Seymour, meanwhile, was struggling financially. In 1827, his publishers Knight and Lacey had gone bankrupt owing him a lot of money. He had married that year and overwork and money worries led to a nervous breakdown in 1830. More recently, he had been illustrating comic text for Gilbert Abbott à Beckett, the editor of Figaro in London, a forerunner of Punch. Later one of the ‘Dickens Circle’, à Beckett was younger than Seymour and the two men eventually quarrelled. He resigned, and à Beckett refused to pay him, ridiculing him in the magazine. The humiliation of the public smear had triggered severe depression, but Seymour returned to Figaro when Henry Mayhew took over as editor. Although at the height of his popularity when The Pickwick Papers commenced, Seymour was on the ragged edge and losing control of his project. The cover of the first issue says it is ‘Edited by “Boz” With Illustrations’, but Seymour’s name does not even appear. He was also struggling to meet Dickens’ requirements, which went far beyond the humorous sporting illustrations originally envisioned and which were his stock in trade. After an argument between the two men at Dickens’ home over the illustration for ‘The Stroller’s Tale’ in the second number, Seymour returned home, worked late into the evening on the new plate and then killed himself with a ‘fowling piece’ (a sportsman’s shotgun).

‘Mr Pickwick leaving Goswell Street’ by Frank Reynolds (1910)

As his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography delicately puts it, ‘Seymour could not brook the mere toleration of his designs, and when to this was added something in the nature of dictation from his collaborator (though couched in the kindest terms), his overtaxed nerves magnified the matter until it grew unbearable.’ Issue 2 went out with Seymour’s three completed illustrations, and Dickens changed the format from the third part, reducing illustrations from four to two per issue in order to increase his text to 32 pages. Seymour was initially replaced by Robert William Buss (later known for his painting Dickens’ Dream), but Dickens was not satisfied with his work and he was dropped after one issue. Buss was replaced by ‘Phiz’ (Hablot Knight Browne), who would go on to illustrate much of Dickens’ later work. Jane Seymour, the artist’s widow and mother of his two children, always blamed Dickens for her husband’s suicide, likening him to Milton’s Satan, although it was his dispute with Figaro that was cited as a cause in the coroner’s verdict of suicide. Seymour was a delicate, sensitive man in an increasingly Darwinian industry. His mental health had been declining for almost a decade, and to lay his death at Dickens’ door would be unfair. His announcement of Seymour’s death in the second number of Pickwick is sombre and respectful:

Some time must elapse, before the void which the deceased gentleman has left in his profession can be filled up: – the blank his death has occasioned in the Society, which his amiable nature won, and his talents adorned, we can hardly hope to see supplied.

After Pickwick became a success, which was far from certain when Seymour died, rumours persisted – largely circulated by Jane and family friends and amplified in some obituaries – that Seymour was the real brains behind the serial. In his preface to the 1867 edition, Dickens decided to set the record straight, stating that ‘Mr. Seymour never originated or suggested an incident, a phrase, or a word to be found in this book. Mr. Seymour died when only twenty-four pages of this book were published, and when assuredly not forty-eight were written.’ In a final, rather ghoulish twist, Seymour’s headstone (removed from St Mary Magdalene Church, Islington, during building work and for many years thought lost) is now on permanent display at the Charles Dickens Museum in Camden.

The tragic Seymour was as much a victim of changing times as anything, and Dickens was changing them. As he’d seen immediately, the sporting club formula was already hackneyed and cliché. But that’s what the industry seemed to want, the deliberately familiar. Advances in printing technology had flooded the market with new weeklies and monthlies, but the content was surprisingly bland compared with that of Regency magazines like Blackwood’s, The London Magazine, and the Edinburgh Review. Miscellanies were popular, mixing nonfiction articles with literary fiction, but the fiction was rarely new. Instead, these magazines republished the literature of the past, Augustan and Romantic, Shakespeare, Spenser, and Milton, along with Classical translations and religious writing such as Bunyon’s Pilgrim’s Progress. Articles were long, learned, and dull. The tone was nostalgic, the humour much like Seymour’s – gently satirising the mores of the middle and upper classes. Contemporary literature, meanwhile, had no obvious champion after the death of Sir Walter Scott and the end of the Romantic period. Dickens was young, enthusiastic, brilliant, and hungry. And he worked fast.

As you read The Pickwick Papers you can feel Dickens growing as an author, transitioning from journalist to novelist. There’s the journalist’s eye for detail, his instinctual ear for natural dialogue, accents, and mannerisms, his nose for a story, and his hard-won knowledge of London life across the social divides. At the start, he is still the sketch writer, observing in his original preface:

The author’s object in this work, was to place before the reader a constant succession of characters and incidents; to paint them in as vivid colours as he could command; and to render them, at the same time, life-like and amusing.

This echoes his preface to the first edition of the Sketches, in which he wrote:

His object has been to present little pictures of life and manners as they really are; and should they be approved of, he hopes to repeat his experiment with increased confidence, and on a more extensive scale.

Sam Weller by ‘Kyd’ (Joseph Clayton Clark (1857-1937)

Pickwick provided the opportunity for the ‘more extensive scale’. The prose is restless – reckless even – eager to move on to the next gag, the next quirky character. Fast and funny, the writing sizzles with edgy, infectious energy. It can be quite disorientating at times, but the overall effect is one of exhilaration. As the innocent Samuel Pickwick and his companions go about their travels, the author and, indeed, the English novel, embark upon a similar journey to return, like Mr. Pickwick himself, changed by the experience.

Dickens opens with a transcript of a Club meeting in which he sends up learned and debating societies (and by implication parliament) something rotten, revelling in pompous and empty rhetoric, obscure personal disputes, and arcane proceedings:

‘MR. BLOTTON (of Aldgate) rose to order. Did the honourable Pickwickian allude to him? (Cries of “Order,” “Chair,” “Yes,” “No,” “Go on,” “Leave off,” etc.)

‘MR. PICKWICK would not put up to be put down by clamour. He had alluded to the honourable gentleman. (Great excitement.)

‘MR. BLOTTON would only say then, that he repelled the hon. gent.’s false and scurrilous accusation, with profound contempt. (Great cheering.) The hon. gent. was a humbug. (Immense confusion, and loud cries of “Chair,” and “Order.”)

‘Mr. A. SNODGRASS rose to order. He threw himself upon the chair. (Hear.) He wished to know whether this disgraceful contest between two members of that club should be allowed to continue. (Hear, hear.)

‘The CHAIRMAN was quite sure the hon. Pickwickian would withdraw the expression he had just made use of.

‘MR. BLOTTON, with all possible respect for the chair, was quite sure he would not…’

There’s already something quite surreal about all this, while Dickens’ artfully contrasts the colloquial with the ridiculously formal as the dispute becomes more colourful. This transcript forms something of a preface in which the mission is stated. We are then swept quickly to Chapter 2 and ‘The First Day’s Journey’, which immediately descends into farce as Mr. Pickwick attempts to interview the cabbie: ‘Mr. Pickwick entered every word of this statement in his note-book, with the view of communicating it to the club, as a singular instance of the tenacity of life in horses under trying circumstances.’ This does not go down well:

‘Here’s your fare,’ said Mr. Pickwick, holding out the shilling to the driver.

What was the learned man’s astonishment, when that unaccountable person flung the money on the pavement, and requested in figurative terms to be allowed the pleasure of fighting him (Mr. Pickwick) for the amount!

‘You are mad,’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Or drunk,’ said Mr. Winkle.

‘Or both,’ said Mr. Tupman.

‘Come on!’ said the cab-driver, sparring away like clockwork. ‘Come on—all four on you.’

The George and Vulture in the City of London

Dickens is clearly writing freely and prolifically, the scene unfolding like a stage comedy with a reliance on quick, snappy dialogue. If you’re coming to Pickwick after reading his later work, the lightness of the prose comes as quite a surprise. (If you know the Sketches you’ll recognise the style immediately.) The man was funny.

The day is saved by the arrival of ‘a rather tall, thin, young man, in a green coat, emerging suddenly from the coach-yard.’ This is Mr. Alfred Jingle, a man of as yet unknown origins, who quickly bundles the travellers away while talking the gathered crowd down:

‘Here, No. 924, take your fare, and take yourself off—respectable gentleman—know him well—none of your nonsense—this way, sir—where’s your friends?—all a mistake, I see—never mind—accidents will happen—best regulated families—never say die—down upon your luck—Pull him up—Put that in his pipe—like the flavour—damned rascals.’

And he continues to talk like this, various triggers eliciting these mini-monologues:

‘Heads, heads—take care of your heads!’ cried the loquacious stranger, as they came out under the low archway, which in those days formed the entrance to the coach-yard. ‘Terrible place—dangerous work—other day—five children—mother—tall lady, eating sandwiches—forgot the arch—crash—knock—children look round—mother’s head off—sandwich in her hand—no mouth to put it in—head of a family off—shocking, shocking! Looking at Whitehall, sir?—fine place—little window—somebody else’s head off there, eh, sir?—he didn’t keep a sharp look-out enough either—eh, Sir, eh?’

Jingle, whose clothes are shabby and who travels light, is adopted as a kind of Cockney Pathfinder, and the group travel together to Rochester by coach, Jingle regaling them all the way about the adventures and the women that he has had, adding bawdy working-class humour to the more middle-class pomposity of the Club. It was the synergy between these two social positions – as was so often the case in Dickens’ later writings – that struck the sparks. Had Dickens come from a more conventional middle-class background himself, like the rest of his literary contemporaries, he simply could not have written like this. He really was streetwise. By the end of the journey, Mr. Tupman is quite beside himself and the two later attend a ball, Jingle having borrowed a suit from Mr. Winkle, who was drunk and asleep at the time. Tupman and Jingle dance with a very merry widow (widows feature heavily in the story), ‘bouncing bodily here and there’ much to the ire of her escort, the volcanic Doctor Slammer of the 97th. Jingle insults him and leaves, and when Slammer’s second appears at the coaching inn the following morning in search of a man with a distinctive bright blue dress-coat, he finds the hungover Winkle, who assumes he must have done something when he was drunk. A meeting is arranged at sunset on the field of honour:

‘The consequences may be dreadful,’ said Mr. Winkle.

‘I hope not,’ said Mr. Snodgrass.

‘The doctor, I believe, is a very good shot,’ said Mr. Winkle.

‘Most of these military men are,’ observed Mr. Snodgrass calmly … The evening grew more dull every moment, and a melancholy wind sounded through the deserted fields, like a distant giant whistling for his house-dog. The sadness of the scene imparted a sombre tinge to the feelings of Mr. Winkle. He started as they passed the angle of the trench—it looked like a colossal grave.

Fortunately, Doctor Slammer arrives and declares ‘That’s not the man!’ There follows a nice running gag in which his second tries to find reasons to continue the duel:

‘Then, that,’ said the man with the camp-stool, ‘is an affront to Doctor Slammer, and a sufficient reason for proceeding immediately…’

‘Or possibly,’ said the man with the camp-stool, ‘the gentleman’s second may feel himself affronted with some observations which fell from me at an early period of this meeting; if so, I shall be happy to give him satisfaction immediately.’

Things seem to be resolved but Winkle is now getting on so well with Doctor Slammer that he invites him back to the Bull Inn for drinks, where they bump into Mr. Pickwick and Jingle…

At the same time, the madness is offset throughout by the inclusion of various short stories, traveller’s tales told told from the chimney corner by incidental characters. The picaresque tradition that Dickens was loosely following provided a precedent for this device in the works of Cervantes, Tobas Smollett, Henry Fielding, and Laurence Sterne. These tales provide a change in tone that breaks up the episodic humour in a counterpoint that is decidedly gothic. You’ll probably recognise some of them from anthologies of Victorian ghost stories, for example ‘A Madman’s Manuscript’, which seems to anticipate Poe; the fairytale-like ‘Bagman’s Story’; and ‘The Story of the Bagman’s Uncle’, a quintessentially 19th century English ghost story about haunted mail coaches. Most interesting of all is ‘The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton’. In this story, a misanthropic and curmudgeonly gravedigger is visited (or dreams he is visited) by the Goblin King and his hosts on Christmas Eve, who terrify him into changing his ways, a plot you might recognise from one of Dickens’ later projects.

But don’t think Dickens’ fame and fortune were assured. Though Jingle managed to steal every scene he was in, the class satire Dickens had set up between this character and the Pickwickians soon started to wear thin. By the third issue (June 1836), the project was in danger of stalling and sales were low, falling from about 1,000 per issue for the first two numbers to barely 400 for Part III. This would all change in the next issue, with the introduction of a certain Cockney boot black, destined to supersede Jingle as the working-class voice of the text, and transform Dickens from a journeyman writer to a literary celebrity and a household name.

Sam Weller is introduced polishing eleven and a half pairs of shoes in the yard of the White Hart Inn, to which Mr. Pickwick and his friend from Dingley Dell, Mr. Wardle, have journeyed in pursuit of Jingle, who has eloped with Wardle’s sister, Rachael, for her money:

‘Look at these here boots—eleven pair o’ boots; and one shoe as belongs to number six, with the wooden leg. The eleven boots is to be called at half-past eight and the shoe at nine. Who’s number twenty-two, that’s to put all the others out? No, no; reg’lar rotation, as Jack Ketch said, ven he tied the men up. Sorry to keep you a-waitin’, Sir, but I’ll attend to you directly.’

Modern merchandise: Royal Doulton’s Pickwick and Weller.

As G. K. Chesterton later wrote, ‘Sam Weller introduces the English people.’ Here was a character to which much of the audience could relate. There’s the same ‘Jack the lad’ working class sensibility, along with a similarly distinctive voice, but while Jingle is an idler and a grifter, Sam is an honest grafter, the face of ordinary humanity. The change was simple but radical. Jingle becomes a fully fledged antagonist, while Sam becomes Pickwick’s true guide to the urban jungle. He’s streetwise and cheeky, but also honest and loyal. And funny. Very, very funny. Sam’s dialogue is resplendent with what became known as ‘Wellerisms’, idiosyncratic proverbs drawing upon surreal analogies, all rendered in phonetic Cockney, with w’s and v’s interchanged, for example:

‘Then the next question is, what the devil do you want with me, as the man said, wen he see the ghost?’

‘There; now we look compact and comfortable, as the father said ven he cut his little boy’s head off, to cure him o’ squintin’.’

‘That’s what I call a self-evident proposition, as the dog’s-meat man said, when the housemaid told him he warn’t a gentleman.’

‘Vich I call addin’ insult to injury, as the parrot said ven they not only took him from his native land, but made him talk the English langwidge arterwards.’

You get the general idea. ‘You’re a wag, ain’t you?’ says Wardle’s lawyer, to which Sam replies: ‘My eldest brother was troubled with that complaint, it may be catching—I used to sleep with him.’ Dickens wrote with cautious optimism to John Macrone that this ‘specimen of London life’ would both stimulate his writing and garner new readers. This was born out pretty much immediately when the Literary Gazette reprinted Sam’s first episode. Although Dickens was not acknowledged as the author, the Gazette’s editor, William Jerdan, wrote to him privately advising him to make Sam a primary character. Sam’s wit and wisdom immediately gripped the public imagination, and in the following number, Dickens had Pickwick hire Sam as a valet and travelling companion, effectively becoming Sancho Panza to his Don Quixote.

You can feel The Pickwick Papers change gear at this point. Sam is obviously the key. He’s a beautifully drawn comic protagonist for a start, worthy of the epithet ‘Dickensian’. And beneath the funny dialogue, there is a big heart and the sharp mind of a natural problem solver. Sam is a survivor, and an honest one at that. In this sense, he is equally an ‘everyman’ hero that working and lower middle-class readers could see themselves in. Whereas Jingle is profligate with other people’s money, Sam earns his and knows how to cut his coat according to his cloth. As he tells the lawyer, ‘we shan’t be bankrupts, and we shan’t make our fort’ns. We eats our biled mutton without capers, and don’t care for horse-radish ven ve can get beef.’

Sam Weller represents the start of a long line of heroes from the golden age of British comedy. We laugh at the world through his eyes, familiar institutions made fresh through his colourful language and outlook (while he’s never too subversive), and he’ll always save the day with a dose of good old British common sense. He’s there, for example, in the characters of Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan, Sid James and Tony Hancock, Terry Thomas, Eric Sykes, Kenneth Williams, Ronnie Barker, Bernard Cribbins, George Cole, Frankie Howerd, and Harry H. Corbett. And through Sam’s support, Mr Pickwick acquires agency. He is no longer passively at the mercy of a world he doesn’t understand, becoming instead a true philanthropist by turning empty talk into action. At the same time, the previously anarchic, sketch-based narrative gains form, evolving into a serial novel with the plot of ‘Bardell v. Pickwick’, one of the most famous legal cases in English literature. The serial’s climax in the Fleet debtor’s prison is far from funny and offers a glimpse (as did some of the Sketches) of the subjects that were to inform Dickens’ mature output as a novelist: poverty and social injustice. Already, the light was being balanced by the dark.

The ‘bounce’ had begun. Unlicensed merchandise soon followed; there were Sam Weller corduroys, puzzles, boot polish, joke books, and even cabs claiming to be driven by his garrulous father, Tony (introduced by Dickens to exploit the brand), as well as Pickwick cigars, playing cards, sweets, toby jugs, and china figurines. Sales jumped from 400 to 4,000 a month, and by the time The Pickwick Papers concluded in October 1837, the number was closer to 40,000. By then, Dickens had become a literary celebrity, and was already editing Bentley’s Miscellany and working on Oliver Twist. From then on, a new form of literary magazine began to dominate the market, based around the brand of a well-known author and driven by a flagship serial, each instalment ending on a cliffhanger. British publishing was never going to be the same, while popular entertainment had entered a new era, one to which we still belong. And it all begins with The Pickwick Papers, nowadays viewed by most literary historians as a minor work, and probably the weakest of Dickens’ novels.

The Pickwick Papers is chaotic, episodic, and melodramatic, but above all, it is extremely funny. It is also a masterpiece. Chaos and genius are not, after all, mutually exclusive. It also remains tremendous fun to read precisely because of all these qualities. If you don’t know Dickens’ early work, then prepare to be surprised and delighted by an irreverent sense of humour that’s as fresh today as it was almost 200 years ago. If you do know it, then why not visit some old friends? Even after all these years, The Pickwick Papers can still make me laugh out loud. As Sam Weller would have it, ‘Avay vith melincholly, as the little boy said ven his schoolmissus died.’ The Pickwick Papers

Main image: ‘Mr Pickwick slides’. Illustration by ‘Phiz’ (H. K. Browne) Credit: Classic Image / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: ‘Mr Pickwick addresses the Club’. Illustration by Robert Seymour. Credit: Lordprice Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Frontispiece showing ‘Mr Pickwick leaving Goswell Street’. Illustration by Frank Reynolds (1876-1953). Credit: AF Fotografie / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Sam Weller by ‘Kyd’ (Joseph Clayton Clark (1857-1937) Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: The George and Vulture, which features frequently in the book. Dickens was a regular visitor in real life, and it is now the home of the City Pickwick Club and The Dickens Pickwick Club. Credit: David Colbran / Alamy Stock Photo.

Image 5 above: Royal Doulton Pickwick and Weller, the property of our director, Derek Wright, who bought it as a memento of a highly entertaining evening at The George and Vulture as the guest of the City Pickwick Club. Credit: Derek Wright

For more information on the life and works of Charles Dickens’ visit: The Dickens Fellowship

Our edition of The Pickwick Papers is here: Pickwick Papers – Wordsworth Editions

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

The Pickwick Papers

Books associated with this article