Bloomsday 2020

On Bloomsday, Sally Minogue celebrates James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’.

Bloomsday won’t be the usual Bloomsday this year. Many virtual events are still being touted on the official Dublin site, and at first glance they look like real events. Indeed some of them are live, with readings and songs from the Martello tower at Sandycove, the setting of the opening of Ulysses, where, in the very first sentence of the novel, ‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan’ satirises the Catholic mass, holding aloft his shaving bowl, and setting the irreverent tone of the whole. But participation this virus-driven year is necessarily virtual (bloomsdayfestival.ie), when the whole point of Bloomsday is to be there. I’ve written in a previous blog about the shenanigans that have grown up round the events of Joyce’s groundbreaking novel – pub crawls, Dublin crawls, Ulysses crawls, often in costume. It recalls nothing so much as Star Trek conventions or devotees of The Rocky Horror Show. The oddity of this determined crossover of literature and life is only accentuated by the notion of people participating in it virtually, possibly dressed up in Edwardian costume at home. But we shouldn’t turn our noses up. Bloomsday is a rare example of the intersection of a difficult modernist novel with a popular response, and Bloomsday was first celebrated by Irish literary luminaries, Patrick Kavanagh and Myles na Gopaleen/Flann O’Brien. Dublin habitués, they certainly weren’t above having a drink in Davy Byrne’s to honour Leopold Bloom’s visit there on June 16th, the day on which all the events of Ulysses take place. I remember on my first visit to Dublin going into a bar in its suburbs, and finding the walls full of photographs and drawings of Maud Gonne, a significant Republican activist and also the woman W. B. Yeats loved, and about whom he wrote many of his finest poems, some of which were also displayed there. It wasn’t part of any tourist trail, and I had wandered in by accident. The political and the literary were celebrated without fuss as people drank their stout and ate their cheese sandwiches. In Ireland, and in Dublin in particular, literature is part of the fabric of the place.

Joyce had to escape that place before he could flourish as a writer. Ulysses was written when he had long forsaken his native land, which makes all the more remarkable the exact geography that lies as a shadow structure in the novel, and which on any normal Bloomsday is traced by thousands of people following the imagined footsteps of the novel. The mythical is just as important as the actual: with the title Ulysses, Joyce draws a direct parallel between his central character Leopold Bloom and the Homeric hero Ulysses, and claims for his novel the status of epic. But as that opening sentence tells us, this is an epic of ordinary life, with shaving bowls jostling the introduction to the Latin mass. Its shifts of tone are one of the remarkable things about it. Just in that first chapter, we move in and out of the conversation between Stephen Dedalus (one of the three key characters of the novel) and Mulligan, covering ‘beastly’ death in general, Mulligan being a medical who sees it every day, and Stephen’s mother’s death in particular. The nature of memory is dwelt on, as the combination of free indirect narration and direct conversation takes us back and forth in time, and in and out of the present. Music hall songs rub shoulders with poetry, some of it, Yeats’, and the Latin Mass. Mulligan’s constantly ironic voice cuts against Stephen’s serious, melancholic thoughts. And all the while they enjoy a good breakfast fry – food being one of the other running motifs in a novel that deals with the bodily functions and fluids, and metaphysics, on a par. Literary references abound, part of the fluidity of time and imagination, with a nod to Homer’s ‘wine-dark sea’ in the original Greek, Shakespearean references, Biblical and liturgical quotation, Nietzsche. All these are laconically, almost absent-mindedly, included, a natural part of a conversation which also includes chat with the woman delivering the milk, the ongoing drama of Mulligan’s shaving routine and the cooking of breakfast.

Joyce had to escape that place before he could flourish as a writer. Ulysses was written when he had long forsaken his native land, which makes all the more remarkable the exact geography that lies as a shadow structure in the novel, and which on any normal Bloomsday is traced by thousands of people following the imagined footsteps of the novel. The mythical is just as important as the actual: with the title Ulysses, Joyce draws a direct parallel between his central character Leopold Bloom and the Homeric hero Ulysses, and claims for his novel the status of epic. But as that opening sentence tells us, this is an epic of ordinary life, with shaving bowls jostling the introduction to the Latin mass. Its shifts of tone are one of the remarkable things about it. Just in that first chapter, we move in and out of the conversation between Stephen Dedalus (one of the three key characters of the novel) and Mulligan, covering ‘beastly’ death in general, Mulligan being a medical who sees it every day, and Stephen’s mother’s death in particular. The nature of memory is dwelt on, as the combination of free indirect narration and direct conversation takes us back and forth in time, and in and out of the present. Music hall songs rub shoulders with poetry, some of it, Yeats’, and the Latin Mass. Mulligan’s constantly ironic voice cuts against Stephen’s serious, melancholic thoughts. And all the while they enjoy a good breakfast fry – food being one of the other running motifs in a novel that deals with the bodily functions and fluids, and metaphysics, on a par. Literary references abound, part of the fluidity of time and imagination, with a nod to Homer’s ‘wine-dark sea’ in the original Greek, Shakespearean references, Biblical and liturgical quotation, Nietzsche. All these are laconically, almost absent-mindedly, included, a natural part of a conversation which also includes chat with the woman delivering the milk, the ongoing drama of Mulligan’s shaving routine and the cooking of breakfast.

If the range of reference can make reading Ulysses seem a daunting task, its best rewards lie in reading it as a flow of multiple consciousnesses, with judicious consultation of the explanatory notes. The more one reads, the more one falls into the nature of its style, and the firm organisational structures act as a strong core, balancing the rich, allusive narrative form. We soon come to know the three central characters, Stephen, Bloom, and his wife Molly Bloom, each of them roughly corresponding to Telemachus (Ulysses’ son), Ulysses himself, and Penelope, Ulysses’ wife. But their story can be read without knowing anything of Homer, because Joyce translates the epic events of the Odyssey into a world we can all recognise, in which buying some kidneys for breakfast, and cooking and eating them, is rendered as important as reflections on mortality and the afterlife. This is not just a method, with bathos arising from the contrast of different levels. Rather Joyce believes in the confluence of these levels, that there is no ‘high’ and ‘low’, but a world in which, with the right way of looking, the heroic can be seen in everything. A small example of this comes in the first chapter, in the description of the old woman who delivers the milk, which is worth quoting at length to give the flavour of Joyce’s style:

[Stephen] watched her pour into the measure and thence into the jug rich white milk, not hers. Old shrunken paps. She poured again a measureful and a tilly. Old and secret she had entered from a morning world, maybe a messenger. She praised the goodness of the milk, pouring it out. Crouching by a patient cow at daybreak in the lush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled fingers quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle. Silk of the kine and poor old woman, names given her in old times.

The mythical figure of the ‘poor old woman’ carrying mystical or magical qualities is strongly present in the Irish tradition (as indeed in many literary traditions). Followers of the wonderful Marian Keyes on Twitter (@MarianKeyes) might recognise it, translated into this most modern of mediums, in her ironic but loving references to ‘Old Vumman’. It’s a trope that could be accused of the romanticisation of the female, though not in Keyes’ perfectly judged, knowing representation. Does Joyce fall into that trap? No, because in Ulysses, no one way of seeing is given precedence. This brief image of the old woman, sanctified in her ordinary task of milking the cow, is seen through Stephen’s eyes, just after we have learnt that he has refused to kneel and pray for his mother on her death bed (an incident drawn from Joyce’s own life). Ironies abound as the youthful Stephen works his way to an understanding, not just of women, but of himself and of his relation to the world. It is important that we sympathise with him – and we do – but we also see him clearly. Women in the novel are, it is true, often seen through men’s eyes, but Joyce triumphantly trumps this with Molly’s final soliloquy. We end the novel seeing the world through her eyes, from within, a major 20th-century novel ending with a female consciousness, proclaiming her sexuality, proclaiming her own sensibility, an optimistic and final yes.

I mentioned above that Yeats’ poem ‘Who Goes With Fergus?’ is quoted in the first chapter of Ulysses, Yeats brought alongside others great and small. Nonetheless, a placing of Yeats in this crucial opening chapter would be a signal, if only of the way in which Yeats had penetrated the national culture and consciousness by this time. We are told by the James Joyce Centre in Dublin that this was Joyce’s favourite Yeats poem, which is somewhat surprising since it is from Yeats’ early 1893 collection, The Rose, full of dreamy landscapes and Celtic myths (and including ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’). As with anything that Joyce quotes in Ulysses, this poem has to be set against many other references, though it is given a particular significance by being associated with Stephen/Joyce’s mother’s death, and ‘love’s bitter mystery’. At the end of the final chapter of Part Two, the long hallucinatory nighttown section, constructed as a play with dialogue and stage directions, Fergus is recalled again, and with him the memory of Stephen’s mother. Bloom, tending like a mother himself to the curled-up body of Stephen, sees his own lost son Rudy. It is a moment of grace.

Joyce first met Yeats in 1902 when he was only 20, and Yeats 37. Only too easy to imagine the swaggering young man dismissing the older one. Though both can be counted as modernists, they come to that from different camps. Yeats was enmeshed in Irish politics; Joyce flew by those nets. To him Yeats seemed an old man, beyond his interest, though at this time Yeats was already a significant figure in Irish cultural politics. I expect Yeats thought he was a pain in the neck. But in later years Yeats introduced him to influential figures, most important of whom was Ezra Pound. Even as Joyce attacked Yeats’ work, he also appealed to him for help when he was desperate, and Yeats always gave help, supporting his appeals to the Royal Literary Fund and for a Civil List pension. In the late 1930s Joyce finally acknowledged the importance of this early support: ‘It is now thirty years since you first held out to me your helping hand’. Yeats was by now an important public man; he had received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923, the year after Ulysses was first published by Sylvia Beach in Paris, to meet a sticky reception. Joyce himself never received the Nobel Prize – probably the most worthy candidate not to do so. Perhaps the most remarkable thing is that two such significant modernist writers shared that same geography of Dublin, breathed the same air, and in their different ways produced work that entirely transcends their native place. Meanwhile, the best way to celebrate Bloomsday is undoubtedly through the supreme virtual act of reading – Ulysses, Yeats, Homer, or anything else.

Wordsworth Editions publish:

James Joyce, Ulysses, and Joyce’s other major works, including Finnegan’s Wake

W. B. Yeats, Collected Poems

Homer, The Odyssey

Main Image: The annual re-enactment of the funeral procession of Paddy Dignam from Chapter 6 of Ulysses, staged by the Joycestagers in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin. Credit: Noel Bennett / Alamy Stock Photo

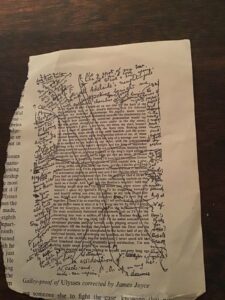

Image above: Galley-proof of Ulysses, corrected by James Joyce

Books associated with this article

Ulysses

James Joyce