Sally Minogue looks at D.H. Lawrence

Sally Minogue picks a path through ‘The Complete Poems of D. H. Lawrence’

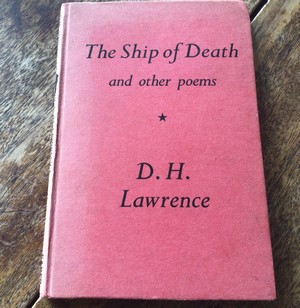

One of my favourite finds from the days when I was a marauder amongst the bookshelves of charity shops, seeking out the characteristic narrow, hard spines of overlooked small volumes, often a faded primary colour, that betokened a poetry collection from the early twentieth century, and possibly (what I was after) that of a First World War poet – is a little book of poems by D. H. Lawrence. Not a first edition, not even an original collection, but a small group of poems gathered posthumously by Faber and Faber and published in a second impression in July MCMXLI (the first impression was in May of the same year, which suggests it was a good seller). Lawrence died in 1930, so this little collection was made eleven years after his death, well into the Second World War. No editor is credited, but Lawrence’s widow Frieda – then still very much alive – is acknowledged for her permission, and the 28 poems span Lawrence’s output from beginning to end.

There could not be a greater contrast between this slim volume and the Wordsworth edition of Lawrence’s Complete Poems, with an introduction and notes by renowned Lawrence scholar, David Ellis. Here are all the poems as directly prepared by Lawrence for the 1928 Collected Poems, as well as the Last Poems edited posthumously by Richard Aldington and Pino Orioli in 1932, from the two notebooks he was working on up to his death. These contain some of his most powerful poems, for example, ‘Bavarian Gentians’, and ‘The Ship of Death’ – the latter title was also given to my prized Faber collection. As the name of that poem implies, it was written as the poet himself embarked on his final journey.

There could not be a greater contrast between this slim volume and the Wordsworth edition of Lawrence’s Complete Poems, with an introduction and notes by renowned Lawrence scholar, David Ellis. Here are all the poems as directly prepared by Lawrence for the 1928 Collected Poems, as well as the Last Poems edited posthumously by Richard Aldington and Pino Orioli in 1932, from the two notebooks he was working on up to his death. These contain some of his most powerful poems, for example, ‘Bavarian Gentians’, and ‘The Ship of Death’ – the latter title was also given to my prized Faber collection. As the name of that poem implies, it was written as the poet himself embarked on his final journey.

The Wordsworth Complete Poems thus charts the full development of Lawrence as a poet, from his earliest works, some of which were published in The English Review and led him to be grouped initially amongst the Georgian school (of which more later), to those he was writing on his deathbed – almost 800 poems in all. It is a much larger body of work than might be imagined by those who know Lawrence principally as a novelist. If he had written poems only, he would still have left a substantial oeuvre. David Ellis is frank about the mixed quality of the poetry: ‘although there is plenty of ore in this volume it does not come without a good deal of dross.’ (xvii) There are critics of Lawrence who might say that is true of many things he wrote; but the quality, originality and fearless imagination of his best writing, poetry or prose, make him a writer who must be read. His poetic voice is as personal to him as that we find in the novels and essays; reading this poetry, flaws and all, gives us a unique vision of the world.

So let us look at some of the nuggets of ore, both the well-known and the less so. That Georgian dimension by which Lawrence was briefly characterised can be seen in the early pages of this volume. ‘Georgian’ has been a much misused and misunderstood term. Once applied as an epithet of praise, to signify a new, fresh generation of poets allied to the accession of a new king at the start of a new century (George V in 1910), it quickly came to represent a throwback to the nineteenth century. Modernism shouldered this poetry out of the canon in a peremptory fashion. For myself, I see in his poems from this early period a very respectable line of tradition from and indeed alongside Thomas Hardy. The Hardyesque elements include a willingness to use dialect as a poetic language (‘The Collier’s Wife’, p. 11; ‘Violets’, p. 26-7); inhabiting a female voice, which Lawrence does particularly successfully throughout his writing (‘Love on the Farm’, pp. 9-11; ‘Monologue of a Mother’, pp. 14-15; ‘Wedding Morn’, pp. 25-6); and an interest in unusual rhythms, line lengths, and verse forms (‘End of Another Home Holiday’, pp. 29-30; ‘Sigh No More, p. 31). My personal favourites from these earlier works are the several poems which deal with the poet’s time as a teacher. Even those which depict a sort of struggle to the death in the classroom give us an utterly original conception of the inner beings of children (in this case boys):

But the faces of the boys, in the brooding, yellow light

Have been for me like a dazed constellation of stars,

Like half-blown flowers dimly shaking at the night,

Like half-seen froth on an ebbing shore in the moon.

(‘A Snowy Day in School’, p. 41)

In ‘The Best of School’ (pp. 18-19), the pupils ‘cling and cleave’ to their teacher and ‘twine my life with other leaves’ as the classroom becomes a pool of light, in which the boys contentedly bask as they work. If this seems a romanticised image, the language and tenor of the poem persuade us of its truth:

this morning, sweet it is

To feel the lads’ looks light on me,

Then back in a swift, bright flutter to work;

Each one darting away with his

Discovery, like birds that steal and flee.

The teacher, a sort of mother bird, offers them ‘the grain / Of rigour they taste delightedly’, but he too is fed :

my time

Is hidden in theirs, their thrills are mine.

The tenderness we see in this poem is there too in one of his most anthologised poems, also from this early period, ‘Piano’ (p. 112). A poem which embodies nostalgia, it manages not to have the faults of nostalgia because it is self-consciously looking at that feeling whilst at the same time surrendering to it. From the first line, we are in the poet’s experience with him:

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom of the tingling strings

And pressing the small, poised feet of a mother who smiles as she sings.

The confident varying of line length mimics the easy back and forth between past and present, while the simple couplet rhyme scheme lends stability, broken only by the feminine ending of the double rhyme ‘clamour’ and ‘glamour’. We are caught up too in that ‘glamour / Of childish days’, our defences down before the poet’s naked emotion. With him, we can ‘weep like a child for the past’. Again there are unmistakable Hardy echoes in this poem, while it remains one of Lawrence’s most distinctive and fully achieved poems.

The collection Look! We have come through! (pp. 143-217) marks a new direction for Lawrence in his life and in his poetry. 1914 brought both his wedding to Frieda (their relationship was of course already a marriage) and the outbreak of a war to which he was vociferously opposed. Eventually, this led to his being charged under the Defence of the Realm Act, where he was in good company with Bertrand Russell (who lost his Trinity College Cambridge Fellowship because of it). Unlike Russell, Lawrence was never imprisoned but he was forced to move from Cornwall where there were suspicions that he was a German spy, in part fuelled by Frieda’s German origins. Till the end of the war they led a hounded and peripatetic existence. Nonetheless, there is a distinct tone of triumphalism in the poems that reflect this period. There is no doubt that Lawrence felt he had found his true self, in part through his relationship with Frieda. His first major novel, Sons and Lovers, had been published in 1913, and to some extent, it exorcised the ghosts of his mother and his first love, Jessie Chambers. And while the war made him miserable to be in a world with whose values he was so much at odds, being in the position of constant opposition in some ways suited him. Some of the best poems of this period celebrate the early phases of his relationship with Frieda, 1912-14, and are tied to particular places in Germany where they initially fled after she left her husband. ‘Bei Hennef’ (pp. 152-153), ‘She Looks Back’ (pp. 155-157), and ‘On the Balcony’ (pp. 157-8) embrace the free verse of Walt Whitman (which Lawrence acknowledges in his Preface to the American edition of New Poems, 1920, reprinted here, pp. 615-619) This is essentially a long paean to free verse which deserves a full reading in itself; no-one has put the power of free verse better:

This is the unrestful, ungraspable poetry of the sheer present, poetry whose very permanency lies in its wind-like transit. … free verse is, or should be, direct utterance from the instant, whole man. It is the soul and mind and body surging at once, nothing left out. … free verse toes no melodic line, no matter what drill sergeant. … We can break the stiff neck of habit. We can be in ourselves as spontaneous and flexible as flame, we can see that utterance rushes out without artificial foam or artificial smoothness. … Such is the rare new poetry. One realm we have never conquered: the pure present.

This is the language of modernism, but the roomy, multitudinous modernism of Whitman rather than the High Modernism of T. S. Eliot. There is room in it for rapture – and the rhapsodic is not to everyone’s taste, especially Lawrence’s form of it. But again, in these poems he captures a rare vision of union and communion between man, woman and nature (as he does also in the novel being written at the same time, The Rainbow):

Here from the balcony

We look over growing wheat, where the jade-green river

Goes between the pine-woods,

Over and beyond to where the many mountains

Stand in their blueness, flashing with snow and the morning.

I have done; a quiver of exultation goes through me, like the first

Breeze of the morning through a narrow white birch.

You glow at last like the mountain tops when they catch

Day and make magic in heaven.

(‘Fronleichnam’, p. 158)

Given the time and circumstances in which they were written, these are remarkably optimistic, even buoyant poems: ‘See, how gorgeous the world is / Outside the door!’ (p. 190)

Lawrence puts nature itself at the heart of his next body of work, Birds, Beasts and Flowers, represented here in smaller sections from p. 219 to p. 331, as organised in Collected Poems. Several of these poems may be familiar to readers, from school or from anthologies: ‘Peach’, ‘Cypresses’, ‘The Mosquito’, ‘Snake’, and various ‘Tortoise’ poems. Lawrence sometimes seems to use nature to write about himself or to characterise humanity, in a strange sort of anthropomorphism, but he is most successful when recognising the otherness of the animal world, or the inaccessibility of nature to human understanding. Here his work is surely a precursor to that of Ted Hughes. Certainly, these are the poems which seem to have found a permanent place in our culture.

To return finally, then, to that ‘Ship of Death’. Lawrence was unwell for most of his life, suffering from a permanently weak chest. His ill health is palpable in many photographs of him. Considering this, and his often rootless and hand-to-mouth manner of living, his creative energy and output are astonishing. Eventually, the depredations of tuberculosis from 1925 onwards brought an inexorable decline and weakening in his last years. David Ellis suggests that his preoccupation with ‘last things’, combined with his failing energy, meant that the short poem now became his ideal form. The last poems thus have a greater bareness of style and economy of language which strips away some of the less appealing excrescences of his earlier poetry:

Reach me a gentian, give me a torch

let me guide myself with the blue, forked torch of this flower

down the darker and darker stairs, where blue is darkened on blueness

(‘Bavarian Gentians’, p. 584)

We almost want to go with him! There’s absolutely no doubt that Lawrence wrote and talked some rubbish. But in his best poems, as here, he carries us along with him, sometimes taking us to regions we could not have imagined otherwise. The poems of his final years confront death with the same verve, curiosity even, that he had always given to life. ‘The Ship of Death’ (pp. 603-606), his masterpiece of this time, is not a short poem, but it is divided into short sections, each of which addresses death with resignation but also with questioning. There is a touching dignity in the way he shoulders the responsibility of this final great subject:

Now it is autumn and the falling fruit

and the long journey towards oblivion.

The apples falling like great drops of dew

to bruise themselves an exit from themselves.

And it is time to go, to bid farewell

to one’s own self, and find an exit

from the fallen self.

The poem is clearly influenced by Lawrence’s admiration of Etruscan culture, wherein the journey to death was but another beginning. But even as it draws on myth for the fabric of the poem, it is of a piece with the writer’s thinking through the whole of his life.

We are dying, we are dying, so all we can do

Is now be willing to die, and to build the ship

Of death to carry the soul on the longest journey.

‘We are dying, we are dying’, echoing as it does Antony’s final words in Antony and Cleopatra, accepts death as a full stop, but the present participle reminds us that we are dying in a larger sense – always dying, even in the midst of life, because death always awaits, whatever fabrications we erect in our lives to keep that at bay: ‘the voyage of oblivion awaits you.’ (p. 606) In this he shares his contemporary Virginia Woolf’s modernist sensibility, which is about as far from the Etruscans as we can get. Yet somehow hope pervades the poem in spite of itself, not, I think, through any belief in an after-life, but from stubborn belief in life itself.

The icon we always associate with D. H. Lawrence is the phoenix arising, and the final poem of this Complete Poems is ‘Phoenix’:

The phoenix renews her youth

only when she is burnt, burnt alive, burnt down

to hot flocculent ash.

Then the small stirring of a new small bub in the nest

with strands of down like floating ash

Shows that she is renewing her youth like the eagle,

Immortal bird.

There’s that stubborn life force again. At the end of Sons and Lovers after his mother’s death, Paul Morel feels himself a tiny speck within a vast landscape, but nonetheless, an upright speck, a being who must move forward to his own life; Lawrence similarly notes in ‘The Ship of Death’ that same ‘fragile soul / in the fragile ship of courage, the ark of faith’, but this time moving towards death. The journey’s all one. And as last words, Lawrence’s take some beating.

Wordsworth editions mentioned above:

The Collected Poems of Thomas Hardy

The Complete Poems of Walt Whitman

D. H. Lawrence, Sons and Lovers

D. H. Lawrence, The Rainbow

Image: Burial room of an Etruscan tomb, Tarquinia, Italy, around 470 B.C

Credit: Zoonar GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Complete Poems of D.H. Lawrence

D.H. Lawrence

The Complete Poems of Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman

Sons and Lovers

D.H. Lawrence