George Eliot turns 200

It’s George Eliot’s and Marian Evans’ 200th birthday! Sally Minogue celebrates with a closer look at her greatest novel, ‘Middlemarch’.

You wait for ages for a feature about George Eliot, and then a glut of them comes along – contemporary artist Gillian Wearing’s television essay, Everything is Connected; Radio 4 programmes at 9-45 am all this week, led by Eliot expert Kathryn Hughes, looking at five of her novels, and through them at the woman herself; and an adaptation of Middlemarch starting on Radio 4 this Saturday, November 23rd. There have also been numerous articles in the print media and online, including a reprint in the current Times Literary Supplement of Virginia Woolf’s centenary assessment of Eliot in 1919. [Links for all of these at the end of this blog]. The bicentenary of George Eliot/Marian Evans’ birth, which we celebrate today, has suddenly brought wide cultural notice across a range of media to a novelist who must be counted one of the greatest of the European tradition. I say European rather than English or British, because her novels are in a continuum with the great nineteenth-century realist works of Balzac, Hugo and Zola; and as I write this, I think too of Dostoievsky and Tolstoy. All of these novelists were grappling with understanding and representing the human condition in a social and historical context. Evans can be rightly placed in this company. And it is a company and culture with which she was well acquainted, being extraordinarily widely read in a number of languages. Just as one example, while her father was dying she tried to distract herself by translating Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologica-Philosophicus. It was apparently ‘such a rest to her mind’.

One of the joys of Gillian Wearing’s film was the burst of colour and imagery she used to express the release of Evans’ trip to Europe immediately after her father’s death. Five days after his funeral in early June 1849, she travelled in the company of the free-thinking Brays, a husband and wife who seem to have had the knack of being, both each and together, great friends to her. Initially, she was exhausted and still distressed from the long period of caring for her father whilst also being in religious disagreement with him. But when her friends were due to return to England, she stayed on alone in Geneva for the whole winter. She spent her 30th birthday there; she was taking stock.

This eight-month period alone in Geneva – at a time, remember, when the unrests of 1848 must still have been resonant – makes me think of Elizabeth Barrett, escaping to Italy in 1846, newly married to Robert Browning, and then espousing passionately the cause of Italian unification and independence. It also calls to mind Charlotte Brontë’s time in Brussels (1842-3), reflected and refracted so brilliantly and painfully in Villette. Evans was later to transmute such a period of foreign reflection to Dorothea Brooke’s wedding journey to Rome with Casaubon in Middlemarch (1871-72). And here we have the nub of Evans’ writerly power. If her European trip had freed her mentally from the ties to her late father and his religion that were already loosed, she reverses this with Dorothea, making her trip to Rome (along with the start of her marriage) a closing-in and a disillusionment rather than the imagined fulfilment. The promise held by Rome makes Dorothea’s disappointment all the sharper:

Since they had been in Rome, with all the depths of her emotion roused to tumultuous activity, and with life made a new problem by new elements, she had been becoming more and more aware, with a certain terror, that her mind was continually sliding into inward fits of anger and repulsion, or else into forlorn weariness. (Chapter 20)

There is an inevitable weakness in Evans’ treatment of these early weeks of marriage, hinted at in that ‘repulsion’. As a woman, Evans flouted social convention, sharing her life intellectually, emotionally and sexually with a married man. But as a writer, she wasn’t able to break the conventions of the nineteenth-century novel by investigating the sexual disappointments of Dorothea (or indeed the sexual demands on the older Casaubon – ‘he had not found marriage a rapturous state’). Dorothea’s desires are scarcely formed before they are disappointed, and she is in no state of self-knowledge to be able to distinguish them from her emotional disappointments. But in the novel’s terms, the two must be conflated, just as Casaubon’s intellectual barrenness is left to stand also for his sexual atrophy. Later writers, such as Thomas Hardy, would be able to explore the distinctions.

Even so, Evans allows us to understand Casaubon too, and she uses the same rather terrifying noun ‘terror’ for his state of mind. If our sympathy is with the youthful Dorothea, we feel too for him, to whom their distancing is ‘a new pain, never having been on a wedding journey before, or found himself in that close union which was more of subjection than he had been able to imagine’. There is a superb turnaround a third of the way through Middlemarch; Chapter 26 opens ‘One morning some weeks after her arrival at Lowick, Dorothea – but why always Dorothea?’ Here Evans turns her gaze fully on Casaubon. This is distinctive of her as a writer. The brilliance of Middlemarch lies in its breadth and diversity, its quiet corners and contemplations, its deferments and uncertainties. There are no absolute heroes or heroines, and if certain characters seem to be offered up as that, we are quickly disabused. All have feet of clay.

Some are more clay-bound than others, and here I think Evans shows her greatest quality as a novelist. Those who are not of the best – Fred Vincy, Casaubon himself, Rosamond Vincy, even the dreadful Bulstrode – are all shown at some point in a good light. No one is entirely condemned in the light of this novelist’s all-seeing eye. As a younger reader, I thought Evans was very hard on Rosamond; she seemed to have created her deliberately as (knowingly) pretty and charming, but also thus meretricious. There seemed some animus here. Consider the following (which echoes ironically the earlier passages of marriage between Dorothea and Casaubon). Rosamond has written secretly to her husband Lydgate’s uncle to ask for financial help, and his angry reply is the first Lydgate knows of her request. Lydgate turns his own anger on his wife:

It is a terrible moment in young lives when the closeness of love’s bond has turned to this power of galling. In spite of Rosamond’s self-control, a tear fell silently and rolled over her lips. She still said nothing; but under that quietude was hidden an intense effect: she was in such entire disgust with her husband that she wished she had never seen him. … In fact there was but one person in Rosamund’s world whom she did not regard as blameworthy, and that was the graceful creature with blond plaits and with little hands crossed before her, who had never expressed herself unbecomingly, and had always acted for the best – the best naturally being what she best liked. (Chapter 65)

Ouch. Yet this is also a version of ‘but why always Dorothea?’ Why always Lydgate? Why are those with good intentions the ones we should understand? Furthermore, Lydgate is the very one who has been captivated by that ‘graceful creature’ with her ‘blond plaits’ and her ‘little hands’. Rosamond has been infantilised before she ever gets to Lydgate; but he furthers the process. As I re-read these passages I see a greater sympathy with Rosamond, if only in their wide human understanding. What is so impressive about this passage is that it refuses the expected: Rosamond’s tear is not one of remorse but of disgust.

Later, the importance of this broad, non-judgemental, human sympathy is given expression through Dorothea’s own thought processes. She has gone to see Rosamond, intending to offer help with the difficulties of her marriage; she finds Rosamond and Will Ladislaw apparently in intimate discourse. Lurking below all this is her own desire for Will. But after a long night of distress and struggle, she replays the encounter: ‘Was she alone in that scene? Was it her event only? She forced herself to think of it as bound up with another woman’s life.’ (Chapter 80) Dorothea reflects on her own part in that moment, the way she has equated the ills of Rosamond’s and Lydgate’s marriage with her own, the way she has ‘been representing to herself the trials of Lydgate’s lot’. And ‘all this vivid sympathetic experience returned to her now as a power … She said to her own irremediable grief, that it should make her more helpful, instead of driving her back from effort.’ Dorothea is left thinking ‘“how should I act now, this very day, if I could clutch my own pain, and compel it to silence?”’

That question underlies all of George Eliot/Marian Evans’ novels, but in an infinitely subtle and complex way. Here it is asked directly only by a fictional character, one of many in Evans’ fictional world. Gillian Wearing’s documentary got to the heart of these works by putting at its forefront the panoply of ordinary people living or working in the places George Eliot/Marian Evans inhabited. They voiced her extraordinary words and implicitly asked themselves the same question. After Dorothea’s long night of the soul (still in Chapter 80), she comes to herself, but also to the outside world:

She opened her curtains and looked out towards the bit of road that lay in view, with fields beyond, outside the entrance gates. On the road there was a man with a bundle on his back and a woman carrying a baby; in the field, she could see figures moving – perhaps the shepherd with his dog. Far off in the bending sky was the pearly light; and she felt the largeness of the world and the manifold wakings of men to labour and endurance. She was a part of that involuntary, palpitating life.

And, as errant human beings, and as readers of these magnificent novels – so are we.

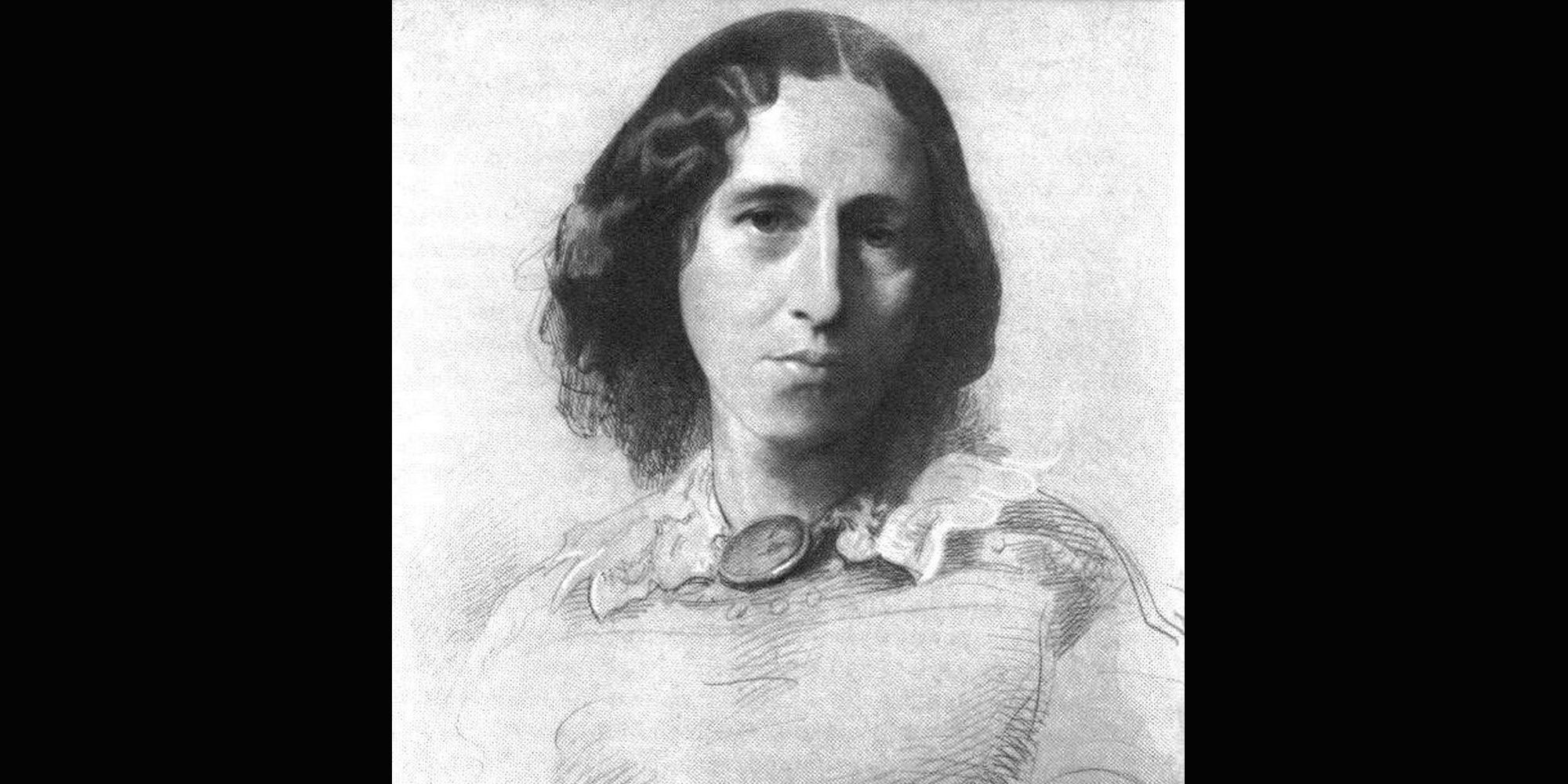

Image: Portrait of George Eliot by Samuel Laurence, around 1860, when Eliot would have been 40.

See my previous blog on The Mill on the Floss, March 22 2019, for a discussion of Eliot’s/Evans’ name.

Gillian Wearing’s Everything is Connected was first shown on BBC Four as part of the Arena series. It is available on iplayer for the next 21 days.

‘George Eliot: A Life in Five Characters’, presented by Kathryn Hughes on BBC Radio 4 this week, is available at bbc.co.uk.

Middlemarch starts this Saturday, November 23rd on BBC Radio 4 at 14.45.

Kathryn Hughes’ ‘What George Eliot’s “provincial” novels can teach a divided Britain’, first published November 16, can be found online, theguardian.com

Virginia Woolf’s ‘Pride and Paragon’, November 20, 1919, reflecting on Eliot’s life and work, is reprinted in the TLS, November 15, 2019, and can also be found in a collection of Woolf’s pieces for the TLS across 30 years, Genius and Ink, published by TLS Books, out this week.

Books associated with this article