Jane Austen 200

On the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s death, Sally Minogue pays tribute to her final novel, ‘Persuasion’.

Jane Austen’s novels have always been carefully distinguished and categorised by her readers. Pride and Prejudice is the premier novel, beautifully structured, bookended by the most brilliantly ironic opening sentence in English literature (‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.’), and a closing sentence which speaks to the opposite of that irony. Its final words (‘uniting them’) endorse the completion and satisfaction of romantic love through marriage to counterbalance the power of money suggested in its opening ones. Sense and Sensibility is a novel which explores – rather cautiously and judgementally – powerful emotion. Emma is the novel we all secretly love, because we admire Emma’s free spirit; that is restrained in the end by Knightley – but some among us might happily be restrained by a Knightley. Mansfield Park is the novel we all secretly, or not so secretly, hate, in spite of its new credentials as radical. Northanger Abbey is a sport – a playful skit on literary fashion rather than a serious novel, albeit a hugely enjoyable one.

For an account of current critical thinking about Austen, and new forms of presentation of her work, see The TLS article – Whatever her persuasion

But Austen’s final complete novel, Persuasion, published after her death, sits somewhat uneasily in her body of work, and possibly heralds a fresh direction for her fiction, which sadly she was unable to pursue. Its heroine, Anne Elliot (unlike Austen’s other heroines who are at the youthful start of their adult lives) is, at 27, judged by her society and her family to be an older woman whose ‘bloom had vanished early’ (5). We are reminded of poor Anne’s lost bloom several times in the first few chapters. The love story which usually occupies the narrative of an Austen novel, albeit with many twists and turns, is here the back story. And while all of Austen’s novels find their narrative completion in marriage, Persuasion leads its heroine, and we as readers, to a marriage which is so hard won that until the final pages of the novel, neither heroine nor readers believe it will come about. The central subject of this novel is, for its main body, the pain of extreme regret.

The source of that pain is revealed in chapter 4: Anne, at 19, had met a naval captain, Frederick Wentworth, and they had fallen ‘rapidly and deeply in love’, and become engaged (20). She then withdrew from their engagement, ‘persuaded to believe [it] a wrong thing – indiscreet, improper, hardly capable of success, and not deserving it’ (21). Anne’s mother having died when she was 14, leaving her motherless through the formative years of her youth, the maternal role instead has been filled by Lady Russell, a friend of her late mother, who fulfils her perceived duties with a zeal that has more to do with her own satisfaction than with Anne’s happiness. Under Lady Russell’s influence – her persuasion – Anne in her youth has given up what she most wanted. She must live with the decision itself and its consequences: ‘Her attachment and regrets had, for a long time, clouded every enjoyment of youth; and an early loss of bloom and spirits had been their lasting effect’ (21).

As the pagination here indicates, this early, powerful happiness and then its loss is dealt with in the briefest of accounts. But we are left in no doubt of its effect on Anne’s life. No man she has since met can compare with Wentworth ‘as he stood in her memory (21); furthermore, ‘Anne, at seven-and-twenty, thought very differently from what she had been made to think at nineteen’ (22). In maturity, she has reflected on a crucial decision in her life, and found it mistaken: ‘She was persuaded that under every disadvantage of disapprobation at home, and every anxiety attending his profession, all their probable fears, delays and disappointments, she should yet have been a happier woman in maintaining the engagement than she had been in the sacrifice of it’ (22). It is made clear that Anne’s regret is not based on any material consideration; but as luck would have it, Wentworth ‘had distinguished himself … and must now … have made a handsome fortune’ (22). Well he would have, wouldn’t he? There is the added twist that, Sir Walter having managed his finances very badly, his family seat, Kellynch, must be let, and it is to be let to Captain Wentworth’s sister. If this is comeuppance for Sir Walter, he of course does not recognise it; for Anne, it is another twist of the knife.

Thus the stage is set for the rest of the novel, and what is a pain for Anne is also an opportunity, and with it, hope is revived and then suppressed at key narrative moments. Always for Anne, there is the horrible possibility that either Wentworth no longer cares for her, or that the same social forces which directed her in youth will work against her again. In this of all her novels, Austen shows most clearly the difficulty for women of being unable to speak of their feelings within the confines of polite society. As readers, we are shown Anne’s feelings at a remove, through the free indirect narrative; so even here we do not get direct access to her thoughts and feelings. The constraint society applies to her is applied also to us. But through that her emotion bursts, like wine peeping through her scars (Antony and Cleopatra, III.xiii.191). On her first brief meeting in society, after eight years, with the man she had loved and rejected, ‘a thousand feelings rushed on Anne, of which this was the most consoling, that it would soon be over. And it was soon over. … Her eye half met Captain Wentworth’s; a bow, a curtsey passed; she heard his voice – he talked to Mary; said all that was right; said something to the Miss Musgroves, enough to mark an easy footing; the room seemed full – full of persons and voices – but a few minutes ended it’ (45). This is almost modernist. If we found it in a Virginia Woolf novel we would admire the way the writer takes us into Anne’s consciousness whilst still apparently describing objectively the happenings of the external world; the sense it gives of Anne’s acute awareness of everything Wentworth does while being enclosed in the tumult of feelings she cannot betray, and which are revealed instead by the many semi-colons which give a sense of hurry and fragmentation, even breathlessness. Only afterwards do we hear Anne’s actual voice: ‘“It is over! It is over!” she repeated to herself again, and again, in nervous gratitude. “The worst is over!”’ (45-46).

There is suppressed agony here, which finds an echo in Charlotte Brontë’s heroines Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe. Brontë famously disliked Austen, writing in 1850 to William Smith Williams, the elder partner in her publishing firm Smith, Elder: ‘what throbs fast and full, though hidden, what the blood rushes through, what is the unseen seat of Life and the sentient target of Death – this Miss Austen ignores’. Charlotte Brontë was commenting on the novels her publishers had sent to her: Sense and Sensibility, Emma, and Pride and Prejudice. Would Persuasion have altered her view? Probably not. Brontë was opposed to what she saw as Austen’s self-confinement as a writer. But in Persuasion, what Austen speaks to is precisely the constrained emotion of her subject – an emotion which indeed ‘throbs fast and full, though hidden’. Anne Elliot suffers fully as much as Jane Eyre or Lucy Snowe in feeling passions that she must subdue, and in this, she is the most interesting of Austen’s heroines – and likewise, she tests Austen’s capacity to express her inner conflict, and extends her narrative art.

We have the evidence of this, remarkably, in alternative endings to Persuasion. Austen originally wrote a final chapter to Volume Two in which Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth confront each other with their feelings as a resolution to all that has gone before. (This chapter is reproduced as an appendix in the Wordsworth edition.) Austen replaced this with the current chapters 11 and 12 of Volume Two (the ending all readers know), in which Austen brilliantly displaces a direct confrontation and declaration between the two onto a conversation Anne has with Wentworth’s friend Harville. (Austen’s handwritten manuscript of these chapters – the only manuscript material from her finished novels to survive – can be studied at The British Library.) Their discourse is about the relative depth and constancy of feeling as regards men and women. Quite a conversation to be having; and Wentworth is at hand to overhear it. Through it he understands that Anne’s feelings have remained constant to him; in the instant, he writes a letter re-affirming his own feelings. In this rewritten ending, everything is at a remove, as befits this story of repressed, long-held feelings, of love renewed rather than in its first flush, of a society in which it is difficult to speak directly, especially for women. ‘Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story … the pen has been in their hands’, says Anne to Harville; but here Austen gives her the chance to tell her own story to the listening men, and to speak to the one man she wants to hear her, without addressing him directly. As Wentworth sits writing of his feelings, Austen wields her pen on behalf of Anne, and of all women.

Anne Elliot and Frederick Wentworth almost miss each other all over again, largely because they are unable to declare themselves directly to each other. This is in part a product of their social milieu. But it is also a product of being human, for to speak of one’s feelings is to expose them to possible rejection. Even in the twenty-first century with its multitudinous forms of communication, where sexting is commonplace, and social media exaggerations and simplifications of feeling abound, making a personal declaration of love remains difficult. Ask any young woman – and any young man.

Further reading

Claire Tomalin, Jane Austen: A Life, Penguin, 1998

For information about the many events marking the bicentenary of Jane Austen’s death, visit janeausten.co.uk

Books associated with this article

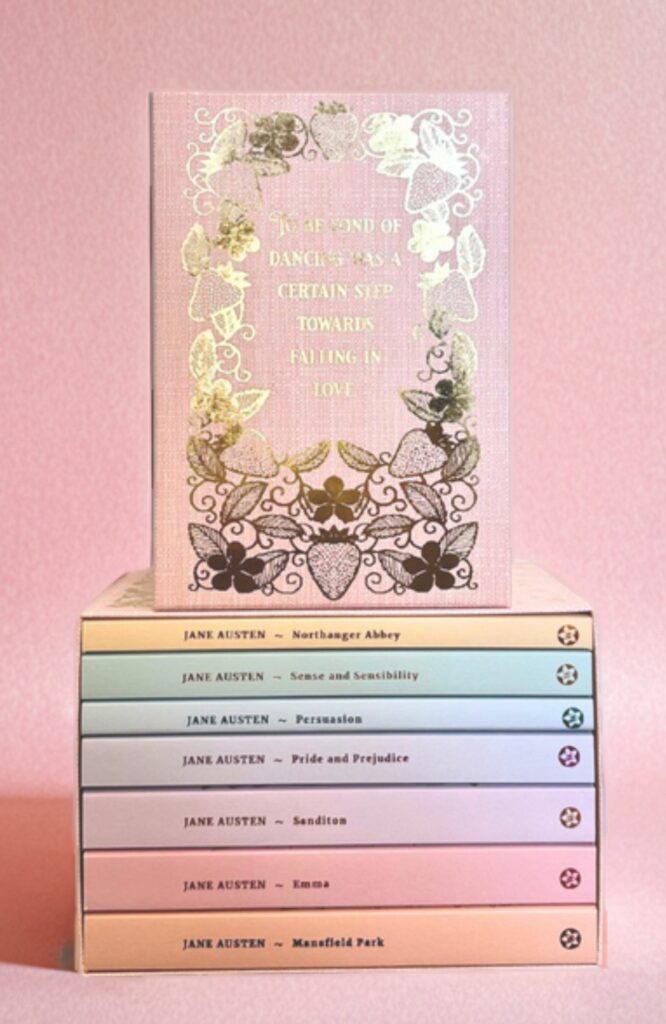

The Complete Jane Austen Collection

Jane Austen

Persuasion

Jane Austen