Sally Minogue looks at Katherine Mansfield

‘I am a writer first’*: Sally Minogue looks at the work and the life of Katherine Mansfield.

When I went along to the university library to flesh out my knowledge of Katherine Mansfield, I was surprised at the number of biographies available there about her. Five at least since the 1970s, one of which is a revision and extension by Anthony Alpers of his earlier biography; and add to that the Collected Letters in 4 volumes and The Poems, both under the definitive Oxford imprint; the Critical Writings from Macmillan; and the Notebooks edited by Margaret Scott, a key scholar of Mansfield and of the period. All of this scholarship comes in the wake of the exhaustive publishing of Mansfield’s work, and a version of her life, soon after her death, by her husband John Middleton Murry.

To put it bluntly, the scholarly and especially the biographical paraphernalia surrounding Katherine Mansfield far outweighs the presence of her fiction in the canon and the recognition of her work by the general public. Murry first kept her work alive, not only because he was Mansfield’s husband but because he believed in her. The excrescence of critical and biographical interest from the 1970s onwards was driven by the rise in feminism and feminist criticism. Mansfield was a clear case of a woman writer who should be foregrounded as playing a key role in the formation of modernism, alongside her close friend D. H. Lawrence. Her relationship with Virginia Woolf, personal and professional, also placed her at the heart of modernism. But the fact that even now I am contextualising her in terms of these two modernist giants reflects the fact that she has always been seen as lesser than them. How far is that a fair judgement?

To put it bluntly, the scholarly and especially the biographical paraphernalia surrounding Katherine Mansfield far outweighs the presence of her fiction in the canon and the recognition of her work by the general public. Murry first kept her work alive, not only because he was Mansfield’s husband but because he believed in her. The excrescence of critical and biographical interest from the 1970s onwards was driven by the rise in feminism and feminist criticism. Mansfield was a clear case of a woman writer who should be foregrounded as playing a key role in the formation of modernism, alongside her close friend D. H. Lawrence. Her relationship with Virginia Woolf, personal and professional, also placed her at the heart of modernism. But the fact that even now I am contextualising her in terms of these two modernist giants reflects the fact that she has always been seen as lesser than them. How far is that a fair judgement?

Here we must invoke the fact that Mansfield came from New Zealand, in her time a distant outpost of the British Empire; England was still the mother country, towards which writers gravitated. Only belatedly have we come to appreciate the particular experience and attendant voice that might have sprung from that experience. With the hindsight of post-colonial criticism, we can understand the outsiderish-ness of Mansfield’s vision, which gives her work an idiosyncratic tone and a take on consciousness which is entirely informed by her sense of elsewhere. If we add in to this Mansfield’s sexual experimentations, whether these were uncertainties or, as they might now be interpreted, enriching awarenesses of possible identities, we see how her personal life might have been extraordinarily difficult, but at the same time her writing life open and original, both informed by her utter determination not to follow the prescribed path. And what difficult people and cultures she had to deal with! Ottoline Morrell and Virginia Woolf, both culturally snobbish in their different ways and catty to boot, never mind the whole Bloomsbury set-up. As Angela Smith attests in her Katherine Mansfield: A Literary Life, Woolf, Morrell and Rupert Brooke were all unpleasantly sneering about her. Here is Woolf: ‘The more she is praised, the more I am convinced she is bad. … She touches the spot too universally for that spot to be of the bluest blood.’ The reference to blood is telling; Morrell notes that she is ‘Japanese in appearance, also I should have said in mind – she had their delicate, exotic vulgarity and sensitively showy bad taste.’ What??! Then, as if Woolf’s and Morrell’s not very carefully hidden racism and disparagement of all things colonial were not enough, she had to contend with an attempt at communal living with Lawrence and Frieda, who couldn’t even live communally with each other.

But enough of the life, even if it did greatly influence both Mansfield’s work and the way it has been perceived. What should we take from that work? First of all, Mansfield was immensely prolific; she published her first writings at 19, and her first short story collection, In a German Pension, at 23. She continued writing right up to her death at the age of 35, and indeed the stories are written in 1921 when she was having treatment for tuberculosis that would kill her come back to her great early preoccupations from the consummate ‘Prelude’ of 1918. ‘At the Bay’ and ‘The Garden Party’, written under the duress of her illness (published in the 1921 collection The Garden-Party and Other Stories) complete a brilliant triumvirate of New Zealand stories. These are not confined to their colonial setting but rather make use of it in a fascinating way to explore precisely the modernist preoccupations with consciousness which occupied Lawrence and Woolf.

Mansfield’s great strength is in recognising the half-hidden states of consciousness, particularly those of women, which the individuals themselves struggle to recognise or articulate, but which they experience powerfully. Sometimes these are states of bliss, but sometimes too, as in the story ‘Bliss’, that rhapsodic awareness is belied by the actuality of the crude lived life. Nonetheless, and even in that apparently ironically named story, Mansfield presents us with the state of mind as it is. It is not belied by what comes after. Yet at the same time, there is always an underside in Mansfield’s stories. It is not so much that nothing is as it appears; rather, it is as it appears and is experienced, but not long after something else can come along to undermine or question what has gone before. This can come from within or without. Sometimes it happens alongside.

In Mansfield’s best stories, life shifts, sometimes for and within a moment, sometimes for good. Saying ‘for good’, I mean of course – forever. But the shift is, also, for good, in the sense that it brings some insight or understanding, even an epiphany in the Joycean sense. And as that happens, something shifts for the reader too. In true modernist tradition, Mansfield keeps the reader onside. These moments of truth are perhaps inevitably and inherently melancholy because they give an insight into the tears of things. But at their most successful they offer that insight as a means to make life richer, even if the richness of understanding is underpinned by an awareness of life’s sadness. Thus the ending of ‘At the Bay’, where the unmarried sister Beryl so desires something other than her current life can give her, and has fantasies of what that might be; but when presented with the actuality of Harry Kember, ‘Beryl was strong. She slipped, ducked, wrenched free.’ (196) Beryl buys her independence by her strength, physical and moral; but there remains a part of her that would have, simply, wanted to succumb. One does not belie the other.

In this way, Mansfield is of (but also in advance of) her time. Her concentration on female experience and consciousness is steadfast, and here she is occupying the same ground as Woolf. But perhaps the short story form allows her small, concentrated explorations and bursts of understanding to be more powerful than if more fully explored in the novel form. Women can be both subjugated and distressed, the victims of their own lack of confidence or knowledge (as in ‘The Little Governess’ or ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’). But they can also be central and significant, as in ‘An Indiscreet Journey’, where the woman takes the initiative to travel to the Front during the First World War (a sort of inverse version of ‘The Little Governess’). In ‘Prelude’ and ‘At the Bay’, the married women are undoubtedly at the centre of things, their agency derived precisely from their lack of activity in the world; the men with their worldly lives and their self-importance are accordingly, unexpectedly, uncentred. Mansfield is extremely good on marriage, observing it again with that sceptical, outsider eye, yet also aware of the centrality and power it can have in the social world, whilst remaining precarious and unpredictable in its internal workings. Mansfield was twice married, but it was her long-time friend Ida Baker whom she called ‘wife’ at the end of her life, and this relationship, although it is generally thought not to be sexual, seems to have answered to something in her, perhaps because Ida allowed her full dominance.

The last word for stories of Mansfield’s that have been little noticed, is those about the New Zealand outback. ‘Millie’, ‘The Woman at the Store’ and ‘Ole Underwood’ explore a world diametrically opposed to that of ‘The Garden-Party’ and ‘Prelude’. Yet they are of the same geography. How did Mansfield know this world? We discover only by the most roundabout of mentions that the narrator of ‘The Woman at the Store’ is a woman. She is one of the riders ranging the outback, and she is who describes the eponymous ‘woman at the store’, one unusual woman describing another. The detail of these stories gives us a sense of a desolate, isolated and bifurcated life; the interiors of the makeshift dwellings are furnished with packing case dressing tables and papered with pages from English periodicals featuring Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. Nothing could be further from the European settings of so many of Mansfield’s stories, or indeed from her affluent suburban New Zealand settings. But the sense of anomie is the same. Not for nothing did Woolf eventually admit: ‘I was jealous of her writing – the only writing I have ever been jealous of.’ Fair revenge for Mansfield. But even better would have been the fact that Woolf surely would have shared Mansfield’s view of what mattered most: ‘More even than talking or laughing or being happy I want to write.’

*Letter to her husband John Middleton Murry, December 12th 1920, in the midst of an epistolary quarrel about Murry’s liking for – and possible affair with – another woman, also a writer. He made the mistake of sending her stories to Katherine for her opinion. Mansfield drew herself up, as it were, against these peccadilloes, and also pulled rank, announcing ‘I am a writer first’. My quotation at the end of the blog is from the same letter.

Reading

Claire Tomalin, Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (Penguin, 1988)

Angela Smith, Katherine Mansfield: A Literary Life (Palgrave, 2000)

Katherine Mansfield, Letters and Journals, ed. C. K. Stead (Penguin, 1977)

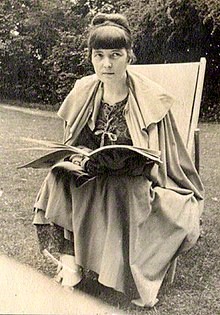

Picture: Mansfield in 1937

Books associated with this article