The Legacy of Sherlock Holmes – Part Two

David Stuart Davies concludes his review of the detectives that followed Conan Doyle’s iconic creation

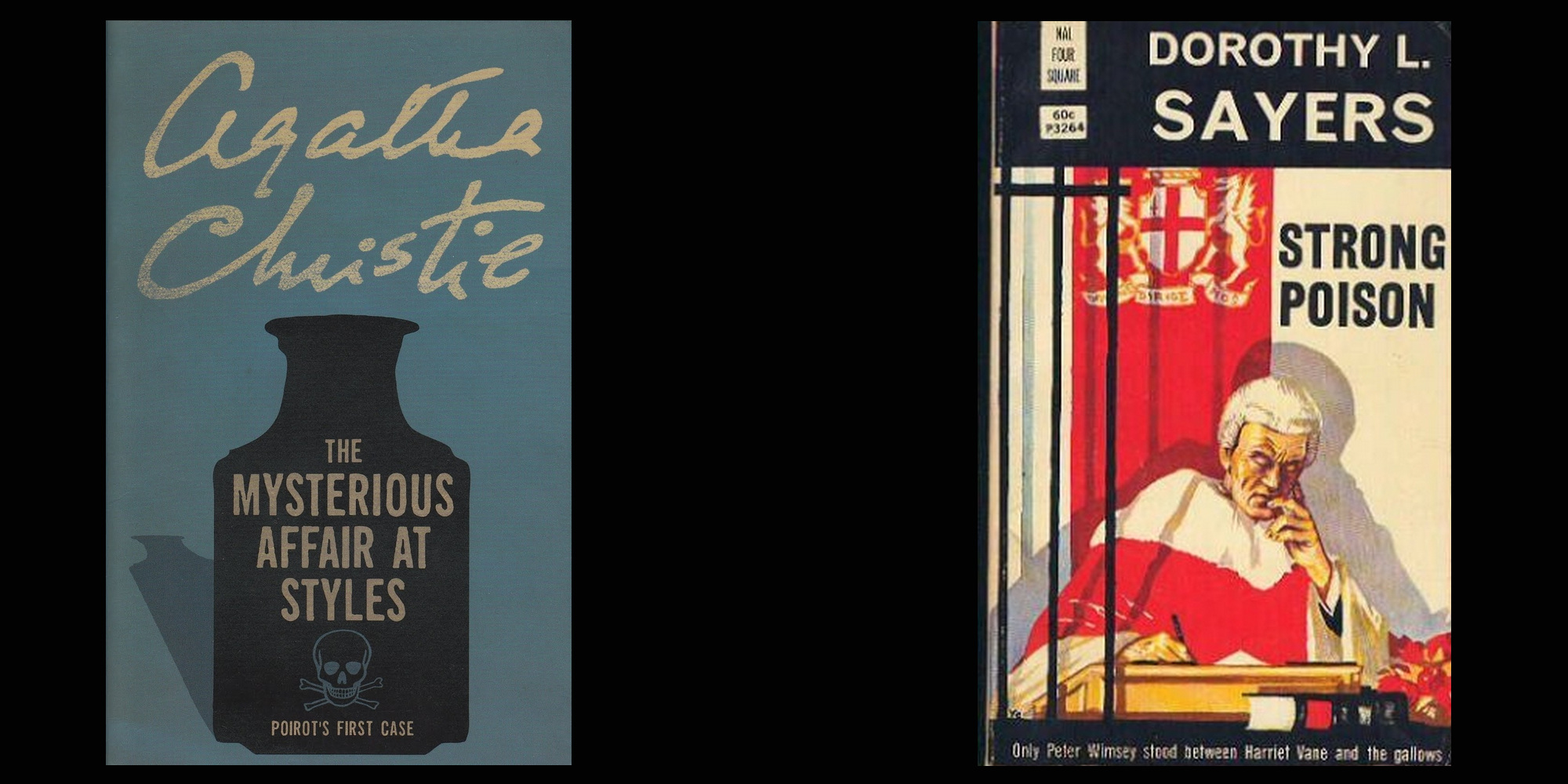

It was in the 1920s that there emerged two of the giants of detective fiction, each created by a clever woman. In 1920, readers encountered the first Hercule Poirot novel, A Mysterious Affair at Styles, by Agatha Christie. Actually, it had been written in the middle of World War I, in 1916, and was first published in the United States in October 1920 before its United Kingdom edition in 1921. Poirot, a Belgian refugee of the Great War, is settling in England near the home of Emily Inglethorp, who has helped him to his new life. His friend Hastings arrives as a guest at her home. When the woman is killed, Poirot uses his detective skills to solve the mystery thus starting on a long and successful career as a private detective. Like Holmes, he saw and observed and, using his ‘little grey cells’, was able to reach remarkable conclusions.

It was also in the 1920s that Dorothy L. Sayers introduced Lord Peter Wimsey, her aristocratic sleuth, to the reading public in the novel Whose Body. Wimsey is a dilettante who solves mysteries for his own amusement. An archetype of the British gentleman detective, the younger brother of the Duke of Denver, he was born in 1890 and served in World War I. During the war he was injured and suffered a bad case of shell shock for several months afterwards. He eventually recovered, and his compatriot in the war, Bunter, was employed as Wimsey’s manservant. Lord Peter lives primarily in a flat in London and begins investigating crime as a hobby and he’s become known to the police as a competent sleuth, especially to his friend Detective Inspector Parker. Sayers penned eleven novels and several short stories featuring her sleuth from 1923 to 1937. Sayers once commented that Lord Peter was a mixture of Fred Astaire and Bertie Wooster, which is most evident in the first five novels. However, Lord Peter later developed into a more rounded character, especially when Sayers introduced the detective novelist Harriet Vane in Strong Poison (1931) as Wimsey’s love interest. She eventually accepts his proposal of marriage at the end of Gaudy Night (1935). In the final novel of the series, Busman’s Holiday (1937), they are firmly ensconced in a happily married state.

The 1920s also saw the arrival of many other interesting private investigators treading similar pathways to the one travelled by Sherlock Holmes. In the USA Willard Huntington Wright, taking on the name S. S. Van Dine, wrote cunning mysteries for his smooth sophisticated American sleuth Philo Vance to solve. Vance, a bit of a prig, prompted humourist Ogden Nash to observe, ‘Philo Vance needs a kick in the pance!’ In Britain, towards the end of the 1920s, Margery Allingham introduced another eccentric, sharp-minded sleuth, Albert Campion. He is a mysterious, upper-class character, working under an assumed name. He floats between the refined echelons of the nobility and government on one hand and the shady world of the criminal class on the other, often accompanied by his scurrilous ex-burglar servant Lugg. During the course of Campion’s career, he is sometimes a detective, sometimes an adventurer. As the series progresses he works more closely with the police and MI6 counter-intelligence. Like Wimsey, he falls in love, gets married and Campion even has a child. As time goes by he grows in wisdom and matures emotionally. As Allingham’s powers developed, the style and format of the books moved on: while the early novels are light-hearted murder mysteries or ‘fantastical’ adventures, The Tiger in the Smoke (1952) is more character study than a crime novel, focusing on the serial killer Jack Havoc.

The 1920s are now regarded as the golden age of crime fiction where the whodunit reigned supreme. The bookshelves were awash with charismatic sleuths of all hues, idiosyncrasies and persuasions but all, in one sense or another provided a darkened, distorted mirror image of Holmes, each one of them triumphing over the bumbling inadequacies of the official police. In the thirties, we had John Dickson Carr’s Dr Fell, Ngaio Marsh’s Inspector Alleyn ( a policeman, but a rich aristocratic one who was, in essence, an independent agent), Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple and Dashiell Hammett’s Nick Charles amongst others. However, with the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the reader’s appetite for murder and dilettante detectives waned and in the early post-war years, there was the gradual emergence of the police procedural, novels which concentrated on the routine institutionalised process of catching the criminal.

It seemed the day of the private detective in the shape-shifting mould of Sherlock Holmes was over. However, gradually, in the 1960s we saw the arrival of the individualistic rogue cop. Although part of the police establishment, this idiosyncratic detective with a strong independent streak functioned essentially as a lone agent. He (and it was inevitably a ‘he’) ploughed his own furrow and like Holmes took risks, saw possibilities hidden from less acute colleagues and more importantly made brilliant deductions which led to the solving of the crime. In this roll call, we have P.D. James’s Adam Dalgliesh, Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse, Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus and Peter Robinson’s DCI Banks. Although part of the police establishment, these fellows, along with a whole bunch of other less famous fictional cops, are in essence following on in the tradition of Sherlock Holmes: using their brains, seeing and observing and making the most brilliant connections between clues and incidents to bring the malefactor to justice. Conan Doyle no doubt would be surprised but I suspect rather proud too that Sherlock Holmes has inspired and informed such a wealth of literary entertainment.