Sally Minogue looks at Mrs Dalloway

BBC Radio 4 this week begins a 10-part reading of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. Sally Minogue looks at the Modernist context as Woolf conceived and wrote her fourth novel.

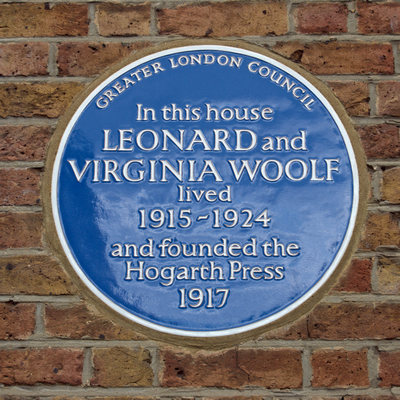

As if to remind us of its incontestable worth at the very moment when it is under greatest threat, the BBC is this year coming out all cultural guns blazing to celebrate the centenary of the birth of Modernism, affixing it to the year 1922. By a nice symmetry, issuing from the BBC’s collective consciousness, this coincides with the centenary of the BBC’s own birth in 1922. Otherwise this is an arbitrary choice of date for the celebration of something at once so amorphous and so contested as Modernism. Virginia Woolf, central to that movement, placed its arrival much earlier: ‘On or around December 1910, human character changed.’ (‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’, 1923) Woolf is herself being captious, as we can tell by that ‘On or around’, qualifying the specificity of the deliberately large claim that ‘human character changed’; but she was also making a serious point. She is generally thought to be referring here to the impact of ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’, a show curated by Roger Fry at London’s Grafton Galleries, including the work of Gauguin, Van Gogh and Cezanne, the first occasion on which the British public had been exposed to these artists en masse. So if 1910 is at the early end of the spectrum of dates for the birth of Modernism, 1922 perhaps marks its apotheosis. Certainly that was the year in which significant publications took place, the most notable of these being James Joyce’s Ulysses (the subject of a blog to come) on February 2nd 1922, in Paris by Sylvia Beach. It was followed in December of that year by T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published first in book form, including the iconic notes, in America by Boni and Liveright. Its first British publication in the form we know now was by the Hogarth Press in September 1923 – the Press run by Leonard and Virginia Woolf.

James Joyce’s fledgling Ulysses was also urged on the Woolfs for the Hogarth Press, as early as April 1918, by Harriet Weaver, and Virginia and Leonard ‘looked at’ the first four chapters of the five then written. Woolf notes in her Diary (April 18th but reporting back on the events of April 14th) that ‘[it] seems to be an attempt to push the bounds of expression further on’. This was at best a lukewarm reaction, though, other things being equal, it was the sort of work they would have supported, and by September 20th 1920 Woolf was saying, ‘Perhaps we shall try to publish it’. Eliot, whose visit she is describing in this entry, is by then the novel’s great advocate – ‘extremely brilliant, he says’. But the novel’s possible length and the nature of its content, challenging current obscenity laws, would have been a problem for their small press. (Just the act of type-setting a work was extremely laborious, as is evident from many entries in the Diary, and Virginia and Leonard did much of the arduous physical work themselves.) These early references to Joyce’s work in-progress in the diaries for 1918 and 1920 show a latent unease. In the 1918 entry Woolf is already associating the novel with ‘filth’, and in the 1920 entry she sidelines the novel to note that Joyce ‘is an insignificant man, wearing very thick eye-glasses … dull, self-centred and perfectly self assured’. Yet just a few days later she is still ruminating on the discussion of Joyce with Eliot and noting that it ‘cast a shade upon me’. Her writing of Jacob’s Room ‘has come to a stop’ and ‘I reflected how what I am doing is probably being better done by Mr. Joyce’. Fragile is the writer’s ego; Eliot’s praise of Joyce has put Woolf’s writing in the shade.

James Joyce’s fledgling Ulysses was also urged on the Woolfs for the Hogarth Press, as early as April 1918, by Harriet Weaver, and Virginia and Leonard ‘looked at’ the first four chapters of the five then written. Woolf notes in her Diary (April 18th but reporting back on the events of April 14th) that ‘[it] seems to be an attempt to push the bounds of expression further on’. This was at best a lukewarm reaction, though, other things being equal, it was the sort of work they would have supported, and by September 20th 1920 Woolf was saying, ‘Perhaps we shall try to publish it’. Eliot, whose visit she is describing in this entry, is by then the novel’s great advocate – ‘extremely brilliant, he says’. But the novel’s possible length and the nature of its content, challenging current obscenity laws, would have been a problem for their small press. (Just the act of type-setting a work was extremely laborious, as is evident from many entries in the Diary, and Virginia and Leonard did much of the arduous physical work themselves.) These early references to Joyce’s work in-progress in the diaries for 1918 and 1920 show a latent unease. In the 1918 entry Woolf is already associating the novel with ‘filth’, and in the 1920 entry she sidelines the novel to note that Joyce ‘is an insignificant man, wearing very thick eye-glasses … dull, self-centred and perfectly self assured’. Yet just a few days later she is still ruminating on the discussion of Joyce with Eliot and noting that it ‘cast a shade upon me’. Her writing of Jacob’s Room ‘has come to a stop’ and ‘I reflected how what I am doing is probably being better done by Mr. Joyce’. Fragile is the writer’s ego; Eliot’s praise of Joyce has put Woolf’s writing in the shade.

‘An illiterate, underbred book it seems to me: the book of a self-taught working man, and we all know how distressing they are’ (August 16th 1922)

– this snobbish remark has been petrified into Woolf’s monolithic verdict on Ulysses. I have done it myself: http://bit.ly/2JBQW3K. But in fact this comment was made after she had read only 200 pages – ‘not a third’, as she herself admits. This was one of many repeated attempts at reading it over the several years since ‘looking at’ the first chapters. It’s another ad hominem judgement, more about the (wrongly characterised) man than the work. And it was made as she herself was struggling with the newly conceived Mrs Dalloway. By September 3rd she has however made sufficient progress that now ‘I should be reading the last immortal chapter of Ulysses’. But ‘Badmington’ and various social demands intervene – and ‘Every day will now be occupied till Tuesday week.’ Thus Woolf puts aside one of the most remarkable fictional passages of her time, Molly Bloom’s soliloquy, in favour of a few social calls. Plenty of the anxiety of influence in Woolf’s comments here, which show her writer’s jealous unconscious as rather touchingly transparent. More than once she ‘should be’ reading Ulysses, but isn’t. When she does at last finish it, she notes the difference between reading Proust and Joyce. With Proust ‘The pleasure becomes physical – like sun and wine and grapes and perfect serenity and intense vitality combined. Far otherwise is it with Ulysses; to which I bind myself like a martyr to a stake, and have thank God, now finished – my martyrdom is over.’ (Letter to Roger Fry, October 1922) Interesting that Proust was no threat: even though she declared, ‘Well – what remains to be written after that?’, she had no difficulty in going on writing. With Joyce it was otherwise, as can be seen by the earlier sudden stopping of the flow of Jacob’s Room. Too close to home, too near in age (in her Diary entry, January 15, 1941, on Joyce’s death, she notes ‘Then Joyce is dead – Joyce about a fortnight younger than I am.’), too ambitious in the same areas of the writing imagination as she was. And fulfilling those ambitions ahead of her.

But Woolf is the consummate writer, and a brave one. We can practically feel her pulling herself up by her bootstraps in these entries, chewing doggedly on Joyce, albeit with a bit of indigestion, and spitting him out, then gearing herself up to do something – the same, maybe, but different. And so we come to Mrs Dalloway. The most obvious similarity between the novels is that they obey the old unities of time and place, the time span a strict 24 hour period, the place one city. The third unity of action each writer circumvents through the simple device of expressing human consciousness. The interior monologues central to both novels allow the writers to go wherever they will, just as consciousness does. The structure of the day and place acts as an anchor, but otherwise there are no limits. The unities that are invoked are rendered illusory.

But Woolf is the consummate writer, and a brave one. We can practically feel her pulling herself up by her bootstraps in these entries, chewing doggedly on Joyce, albeit with a bit of indigestion, and spitting him out, then gearing herself up to do something – the same, maybe, but different. And so we come to Mrs Dalloway. The most obvious similarity between the novels is that they obey the old unities of time and place, the time span a strict 24 hour period, the place one city. The third unity of action each writer circumvents through the simple device of expressing human consciousness. The interior monologues central to both novels allow the writers to go wherever they will, just as consciousness does. The structure of the day and place acts as an anchor, but otherwise there are no limits. The unities that are invoked are rendered illusory.

What then does Woolf do to make her novel different?

Prime here is the fact that its central consciousness is that of a woman. Joyce may have inhabited a female sensibility in Molly Bloom’s final monologue, but Woolf sparks her whole novel from the mind of Clarissa Dalloway. Hers is the presiding consciousness, just as Woolf’s is the presiding narrative. I don’t want to say that that narrative is thereby or inherently female. I believe, as did Woolf herself (see A Room of One’s Own), that a man may write of a woman, and a woman of a man, equally well – providing the writer is good. But what Woolf does offer here is a foregrounding of the female experience, thus equalising the importance of a woman’s consciousness with that of a man’s. Alongside Clarissa’s internal thoughts and feelings are set those of Septimus Smith, and here Woolf again does something strikingly innovative. Septimus and Clarissa are as different as it is possible to be in their experience, class and gender; but the resonances between them outweigh those differences and make them nugatory. Both feel the yawning abyss below the normality of life, and at key moments of the novel each suffers an existential vertigo, which in Septimus’ case is actual and fatal, while Clarissa manages to dance away from its edge. But they are bound by the same awareness of death, caught by the repeated motif, ‘Fear no more’. There couldn’t be a better example of the way consciousness annihilates all other organising principles in the novel. By comparison, Joyce’s representation of consciousness is deliberately multifarious rather than unifying.

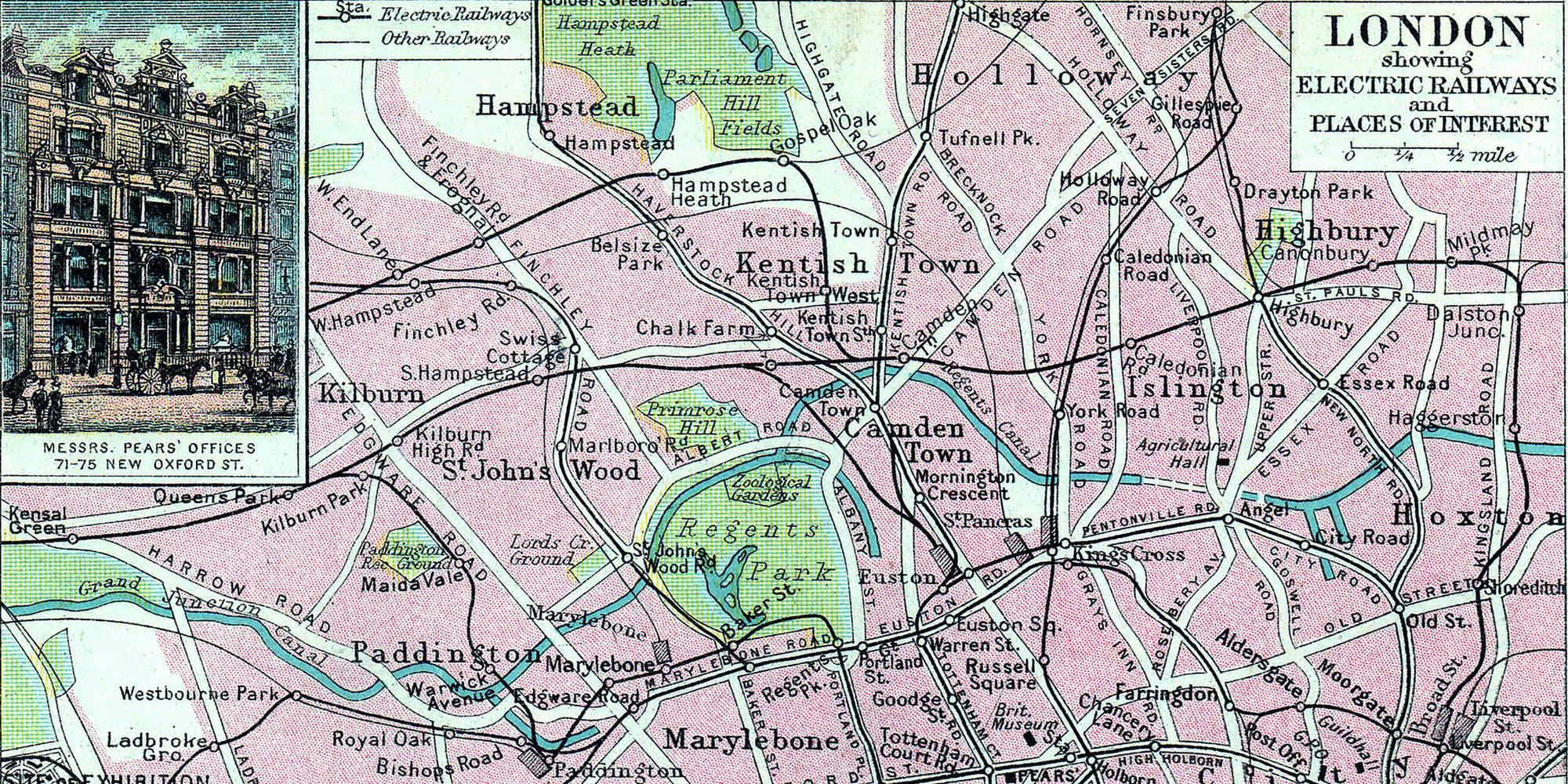

Then for Dublin, we are given London. Something a touch colonialist in Woolf’s impulse here? given that she was writing just as the Irish Free State, independent of British rule, and with Dublin at its centre, was established in December 1922 (another significant 1922 anniversary). But my mind has been dwelling on colonialism of late. More likely she wants to write of what she knows. London is a great city, equal to Dublin, and she uses its geography both lightly and powerfully. Key scenes invoke that geography in some detail, the passing of the important motor car linking Bond Street, where Clarissa is, with Buckingham Palace, and then the overhead aeroplane taking us from the Palace to Regent’s Park and Septimus and his wife Rezia, watching it puff out its smoky messages. It’s not the geography that really matters here but the linked consciousnesses. Nonetheless, as with Joyce’s Dublin, London gives a solid framework to anchor the reader, all the more important perhaps since otherwise all bounds of space and time are crossed. It’s a pity in view of this that the current BBC abridgement of the novel cuts brutally through this careful building up by Woolf of a common consciousness. In the complete version, Septimus believes the aeroplane is sending him messages, whereas the crowd sees eventually that it is spelling the word ‘Kreemo’, advertising toffee. The abridged BBC version leaves out all the references to toffee – thus also leaving out one of the bathetic ironies carefully built up by Woolf.

For understatement is Woolf’s characteristic narrative mode, and she deliberately uses bathos to accentuate the way in which the trivial and the significant jostle shoulders in life. That mental vertigo which eventually leads Septimus to plunge himself onto the railings below his window comes just after Rezia and he are talking conversationally about the hat she has made, and she has been thinking that ‘she could say anything to him now’. Clarissa has a similar moment when she retreats from the comforts of her downstairs home to find that ‘There was an emptiness about the heart of life; an attic room’. One moment she is cocooned, the next exposed and adrift. Then the next moment she is choosing her dress for the party. Critics of Woolf might suggest that the triviality of choosing a dress or a brooch demeans the importance of the terror that strikes her. Woolf wants us to see otherwise: the terror can – and perhaps should – strike anywhere. This is something, I think, that Woolf does better than Joyce. There is a great deal of dwelling on mortality in Ulysses certainly, and there are moments where its chill strikes powerully (I’ll say more on this in my next week’s blog on Joyce). But cheerfulness will keep breaking in in Ulysses, whereas in Mrs Dalloway, death does.

An insistent refrain in Woolf’s reaction to Ulysses is her dislike of its ‘indecency’.

This is in one way surprising; Woolf certainly doesn’t pay much attention to standard social norms, and the Bloomsbury group crossed all sorts of sexual boundaries, as indeed she did herself. But somehow it’s a different matter in writing. The particular examples she invokes from Ulysses are of ‘peeing’ and what she calls ‘forthing’ (from the context she probably means the scene where Leopold is on the lavatory). This looks like embarrassment with Joyce’s unfettered expression in writing of bodily functions and appetites. In this she shared the general view which made Joyce’s work initially unpublishable. But we expect better of a writer, don’t we? Yet it is the very act of writing of such things that makes her uncomfortable. Her imagination stopped at that, whereas Joyce’s didn’t. At the same time, however, she outstrips Joyce by exploring with great freedom the love between women, there both in Miss Kilman’s agonised desire for Elizabeth, and between Clarissa and Sally Seton. Not only Woolf, but her character Clarissa, is frank, untroubled even, in recognising ‘yet she could not resist sometimes yielding to the charm of a woman … she did undoubtedly then feel what men felt’. The description of Sally’s kiss is the one moment she plunges into the past of Bourton to retrieve, a moment as significant in its joy as her glimpses of the void are in their terror. I was pleased to hear that the second radio episode of the novel did give full weight to this.

I have been emphasising here the relationship between Mrs Dalloway and Ulysses because I think that reading the latter (and sometimes not reading it) was a profound influence on the novel she was then writing. It is fascinating to see her worrying away at it and then producing her own novel that is both so like it and so different. I mean no odious comparisons. Each of these works, produced within a few years of each other, is a modernist masterpiece. What is really remarkable is that this short period of time in the aftermath of the First World War produced such a startling outpouring of innovative writing. Next week Ulysses takes centre stage on the centenary of its publication on February 2nd 1922. Meanwhile, the radio abridgement of Mrs Dalloway can give us a taste of the novel; but with its thousand cuts it inevitably destroys Woolf’s fine prose balance, her verbal rhythms, repetitions and juxtapositions, and her fluid movement between the internal and the external, between memory and present consciousness. For those, we need to read every word.

References to Virginia Woolf’s Diary are taken from the Penguin edition in 5 volumes, ed. Anne Olivier Bell.

The essay ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’, can be found in Collected Essays, Vol 3, London, Hogarth Press, 1966.

All of Virginia Woolf’s novels are available from Wordsworth Editions.

BBC Radio Three and Four are broadcasting a number of programmes on Modernism, and specifically on the 1922 centenary. The full schedule of programmes is available at bbc.co.uk (modernism link).

Mrs Dalloway, abridged by Katrin Williams and read in 10 parts by Sian Thomas, is airing daily on BBC Radio Four, January 24-February 4 at midday, repeated at 22-45, and on BBC Sounds.

Main image: A coloured map of London in 1923. Credit: Colin Waters / Alamy Stock Photo

Images above: Blue plaque marking the former home of Virginia and Leonard Woolf. Credit: Mick Sinclair / Alamy Stock Photo

T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf June 1924. Credit: History and Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article