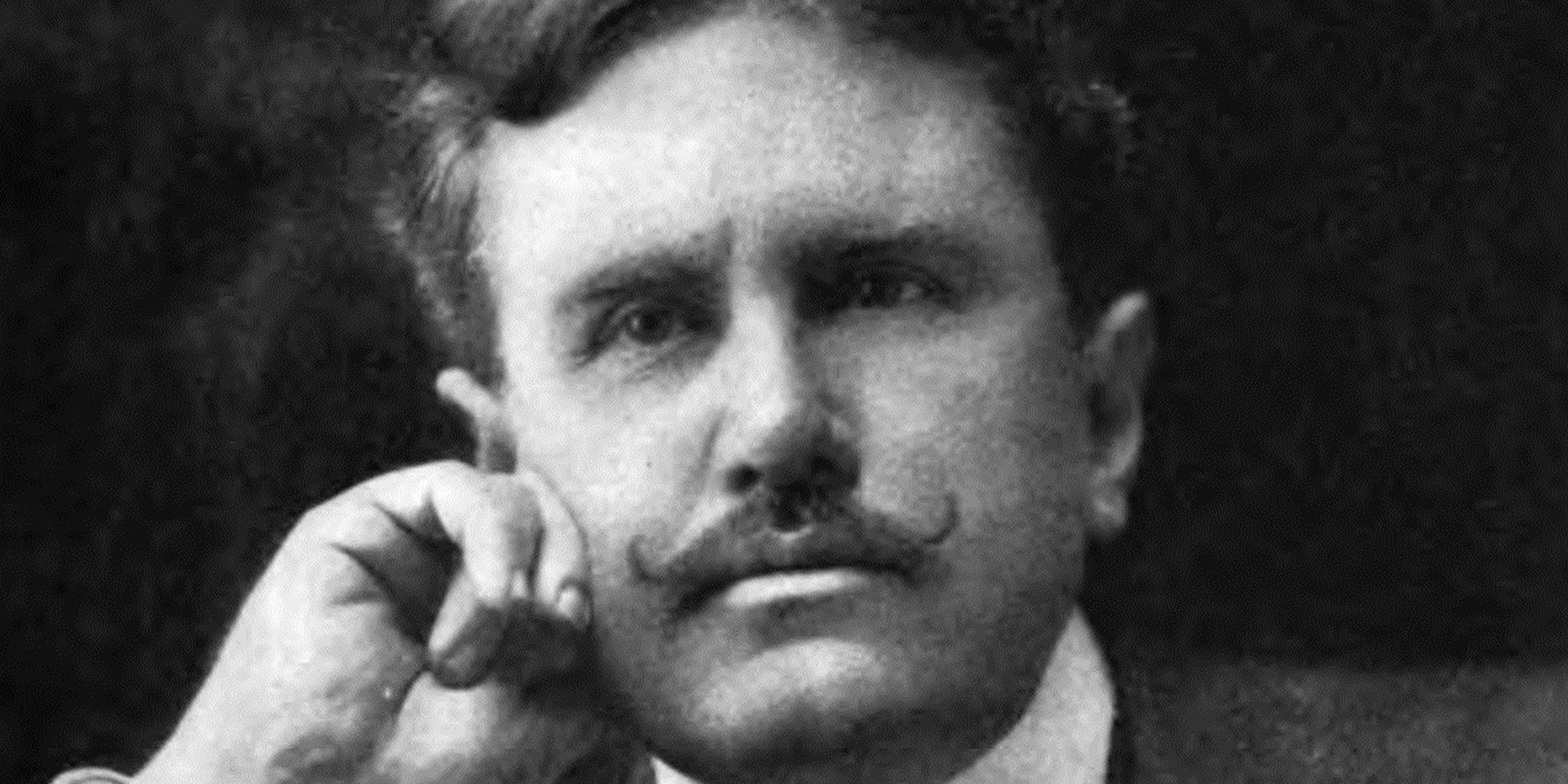

O. Henry

David Stuart Davies looks at the work of O. Henry, an American master of the short story

The art of the short story is a refined one. The creation of a satisfying narrative in miniature – in a few thousand words – is demanding and not easily achieved. However, when a gem of a short tale is realised it has greatness and power equal to the most significant of novels. One of the masters of this genre was William Sydney Porter, who signed his work with the nom de plume O. Henry. It was in his youth when he was ready to submit a set of stories in the hope of having them published that Porter decided to use a pen name in case they were rejected. He read an account of a society function in the local newspaper and chose the name of one of the guests, ‘Henry’ as his new surname. He told a newspaper reporter in 1913 that he chose O as his initial because ‘O is about the easiest letter written.’

Porter was born in Greensboro, North Carolina on 11 September 1862, the son of a doctor. As a young man he moved to Texas to help alleviate a persistent cough he had developed, spending a couple of years on a ranch – which gave him experience which he later utilised his western stories – and then working in the land office and in a bank in Austin. He began writing sketches at about the time of his marriage to Athol Estes in 1887, and in 1894 he started a humorous weekly paper, The Rolling Stone. It was during this period that his life took on the dramatic elements of his own fiction. He was accused by the bank of embezzlement and rather than face the charge, he fled the country and made his way to Honduras, with which the United States had no extradition treaty at that time. He stayed there for six months, during which time he wrote his first full collection of stories, Cabbages and Kings. It was in this volume, which depicted fantastic characters against exotic Honduran backgrounds, that he coined the phrase ‘banana republic’. The book was not published until 1904.

News of his wife’s fatal illness, however, took him back to Austin, and the lenient authorities did not process his case until after her death. When convicted, Porter received the lightest sentence possible, and in 1898 he entered the penitentiary at Columbus, Ohio; his term of imprisonment being shortened to three years and three months for good behaviour. Working in the prison hospital, he was able to write to earn money to support his daughter, Margaret. His stories of adventure in the southwest U.S. and Central America were immediately popular with magazine readers and gave him the encouragement to make writing his profession.

In 1902 O. Henry arrived in New York, a city he dubbed ‘Baghdad on the Subway.’ From December 1903 to January 1906 he produced a story a week for the New York World, writing also for other publications. It is his New York tales which are perhaps his most successful and best-loved. He says in one of these stories that, ‘in the big city the twin spirits of Romance and Adventure are always abroad seeking worthy wooers.’ It was in the collections The Four Million (1906) and The Trimmed Lamp (1907) in particular that he explored the lives of the multitudes of New York concerning their daily routines and dreams.

O. Henry’s stories frequently have surprise endings that enrich the narrative. In his day he was referred to as the American answer to Guy de Maupassant, the French master of the short story. While both authors employed the technique of the twist ending, Henry’s stories were considerably more playful, and less sombre than Maupassant’s and are also known for their witty narration. Most of Henry’s narratives are set in the early 20th century and deal with ordinary people such as policemen, waitresses, clerks and shop assistants. This focus on the ordinary endeared his work to readers. It is also true to note that while the stories are rooted in the period in which they were written, their message and sentiments have a timeless resonance. Take the story ‘The Gift of the Magi’, a heartwarming Christmas tale about a young couple, Jim and Della, who are short of money but desperately want to buy each other a gift for Christmas. It would be very unfair of me to give further details of how this tale unfurls, only to say that it is a classic, the ending of which is moving, sentimental and warmly humorous. In other words, it bears that unique Henry touch. Another favourite of mine is ‘The Last Leaf’, which concerns a poor young woman who is seriously ill with pneumonia. She believes that when the ivy vine on the wall outside her window loses all its leaves, she will also die. Her neighbour Behrman, an artist, tricks her by painting a leaf on the wall. Now read on for the surprising denouement.

But there are so many goodies: Henry wrote over four hundred stories. It is a little-known fact that in ‘The Caballero’s Way’ (1907), Henry introduced his most famous character, the Cisco Kid. In later film and TV depictions, the Kid would be portrayed as a dashing adventurer, perhaps skirting the edges of the law, but primarily on the side of the angels. In the original short story, the only one by Henry to feature the character, the Kid is a murderous, ruthless border desperado, whose trail is dogged by a heroic Texas Ranger. The twist ending is, unusually for Henry, tragic.

O. Henry’s final years were marred by illness. Unfortunately, his personal tragedy was heavy drinking. By 1908, his health had deteriorated and his writing dropped off accordingly. He died in 1910 of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart. The funeral was held in New York City, but he was buried in his home state of North Carolina. Despite the dark and tragic end to his life, he will be not only remembered but revered as a gifted short story writer and he left us a rich legacy of great stories to enjoy.

If you have not had a dose of O. Henry, wait no longer.

Books associated with this article