Mia Forbes looks at The Death of Ivan Ilyich

“The very fact of the death of someone close to them aroused in all who heard about it, as always, a feeling of delight that he had died and they hadn’t. Mia Forbes looks at Tolstoy’s classic novella

Leo Tolstoy wrote The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) after an existential crisis which entirely reshaped his life and which he describes profoundly in A Confession (1882). The two works, although different in kind, present such similar accounts of a man’s struggle with mortality that long passages could be interchanged without disrupting the meaning, tone, or even plot of either text. Tolstoy uses the character of Ivan Ilyich to explore what could well have happened to him had he failed to come to a crucial realization about the meaning of life, or come to it too late.

A well-respected government official, Ivan Ilyich enjoys a standard middle-class life of dinner parties, cards and obligatory family engagements. Everything is done in good taste, “with clean hands, in clean linen, with French phrases, and above all among people of the best society and consequently with the approval of people of rank”. He has a rather simple and satisfactory metric for making decisions: he chooses those courses of action that, a) bring him the most pleasure and, b) are endorsed by his highly placed associates. The two criteria never contradict one another. His marriage, for example, “gave him personal satisfaction, and at the same time it was considered the right thing by the most highly placed of his associates. So Ivan Ilyich got married”.

Ivan Ilyich revels in the praise, attention and envy he receives from others in his class, who of course support and share his hedonistic lifestyle. Each man is out for himself and his own. The novella opens with the announcement of the protagonist’s death, and the first reaction of his colleagues and even his wife is to consider how much they individually stand to gain, hiding their self-interest behind a veneer of sadness and pity. No mention is ever made of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ when it comes to their decisions, words or actions. Ivan Ilyich was “correct in his manner”, yes, but with “correct” determined by social expectations rather than any higher code of conduct. In fact, morality is entirely subsumed by the pursuit of social approval. Tolstoy admits in A Confession that he too was sucked into such a state of moral complacency: “the new circumstances of a happy family life completely diverted me from any search for the overall meaning of life. At that time my whole life was focused on my family, my wife, my children, and thus on a concern for improving our way of life”. Likewise, Ivan Ilyich devotes himself entirely to the enhancement of the family home, a project in which he is so absorbed that he begins to neglect his official duties, let alone any moral ones.

Indeed, it seems to be assumed that, as long as one adheres to the unspoken rules of one’s class, one will be living a good life: “[Ivan Ilyich] succumbed to sensuality, to vanity, and latterly among the highest classes to liberalism, but always within limits which his instinct unfailingly indicated to him as correct”. Thus when he first considers the possibility that he “did not live as [he] ought to have”, the ghastly prospect is “immediately dismissed from his mind… as something quite impossible”. For he had been “liked by all”, and therefore could surely not have done anything so very terrible.

Such values come directly from Tolstoy’s own experience as one of Russia’s elite. In A Confession, he recalls that “ambition, love of power, self-interest, lechery, pride, anger, vengeance – all of it was highly esteemed. As I gave myself over to these passions I became like my elders, and I felt that they were pleased with me. A kind-hearted aunt of mine with whom I lived, one of the finest of women, was forever telling me that her fondest desire was for me to have an affair with a married woman… Another happiness she wished for me was that I become an adjutant, preferably to the emperor. And the greatest happiness of all would be for me to marry a very wealthy young lady who could bring me as many serfs as possible.

“Lying, stealing, promiscuity of every kind, drunkenness, violence, murder-there was not a crime I did not commit; yet in spite of it all I was praised, and my colleagues considered me and still do consider me a relatively moral man”. And so, like Ivan Ilyich, Tolstoy lived without criticism or censure in a meaningless but pleasurable way for many years. In 1869, however, the author had an existential crisis:

“At first I began having moments of bewilderment when my life would come to a halt as if I did not know how to live or what to do; I would lose my presence of mind and fall into a state of depression. But this passed, and I continued to live as before. Then the moments of bewilderment recurred more frequently, and they always took the same form. Whenever my life came to a halt, the questions would arise: Why? And what next?

It happened with me as it happens with everyone who contracts a fatal internal disease. At first, there were the insignificant symptoms of an ailment, which the patient ignores; then these symptoms recur more and more frequently until they merge into one continuous duration of suffering. The suffering increases, and before he can turn around the patient discovers what he already knew: the thing he had taken for a mere indisposition is in fact the most important thing on earth to him, is in fact death”

This is precisely the process of Ivan Ilyich’s decline. His health steadily deteriorating, and he begins a long and terrifying journey towards death. Its suitably trivial impetus is a fall that he suffers while instructing the upholsterer on exactly how he wants the curtains hanged in his thoroughly middle-class new house. At first, he laughs off the accident, but from that point onwards he starts to experience discomfort that soon becomes pain, and weaknesses that soon become debilitating. Upon realising the extent of his illness and being forced to contemplate his own mortality for the first time, Ivan Ilyich sinks into depression. Like Tolstoy’s own, it is a fluctuating state, alleviated when the dying man briefly manages to convince himself that he will live, and intensified when reality returns.

After struggling for months to diagnose and treat a physical pathology, Ivan Ilyich realises that “it’s not a question of appendix or kidney, but of life and death… Why deceive myself? Isn’t it obvious to everyone but me that I’m dying… I was here and now I’m going there! Where?” A chill came over him, his breathing ceased, and he felt only the throbbing of his heart.

“When I am not, what will there be? There will be nothing. Then where shall I be when I am no more? Can this be dying? No, I don’t want to!… Anger choked him and he was agonizingly, unbearably miserable. “It is impossible that all men have been doomed to suffer this awful horror!”

Thus author and character both face by the awful question of why. Why are we alive? If life is simply to end in death, as of course, it must, why do we live? What meaning can there possibly be in an existence that is bound to end in annihilation? In A Confession, Tolstoy isolates four means of escaping from the torment this question brings on any who dares to ask it. The first is the path of ignorance. In failing to ever consider the issue, the blissfully ignorant are free from the terrible shadow of mortality. Tolstoy himself, unfortunately, was not ignorant of the problem, so this was no way out for him. Many characters in The Death of Ivan Ilyich, however, do enjoy a state of ignorance. Ivan Ilyich’s colleagues take comfort in the fact that “he’s dead but I’m alive!”. On seeing the corpse, his friend Peter Ivanovich considers the notion of death “not applicable to him”, and yet he still “felt a certain discomfort and so he hurriedly crossed himself once more and turned and went out of the door”. This awkwardness indicates that the colleagues, undeniably intellectual men that they are, maintain their ignorance of death deliberately, distancing themselves from thoughts of mortality through avoidance and distraction.

And so they actually fall into Tolstoy’s second category, those who pursue an Epicurean means of escape. In this case, people distract themselves from the hopelessness of life, of which they are indeed aware, by diving headfirst into the ocean of worldly pleasures. Lack of imagination, selfishness and immorality prevent such people from contemplating the inevitable. Tolstoy himself “could not imitate these people, since I did not lack imagination and could not pretend that I did. Like every man who truly lives, I could not turn my eyes away from [the problem]”.

Before his illness, Ivan Ilyich’s professional duties “filled his life, together with chats with his colleagues, dinners, and bridge. So that on the whole Ivan Ilyich’s life continued to flow as he considered it should do—pleasantly and properly”, with little time and no desire to consider questions of life and death. After paying the respects demanded by propriety, his acquaintances swiftly discard any thought or conversation of their late colleague, so that “there was no reason for supposing that this incident would hinder their spending the evening agreeably”. Much the same is true of his wife and daughter, who increasingly detach themselves from their dying husband and father as his condition worsens. They continue to engage wholeheartedly in every middle-class pursuit, and by doing so bring upon Ivan Ilyich the realisation that this way of living is “not real at all, but a terrible and huge deception which had hidden both life and death”.

Tolstoy’s proposed third means of escape is that of suicide. “It consists of destroying life once one has realized that life is evil and meaningless. Only unusually strong and logically consistent people act in this manner. Having realized all the stupidity of the joke that is being played on us and seeing that the blessings of the dead are greater than those of the living and that it is better not to exist, they act and put an end to this stupid joke”. He admits that this path was attractive to him, but he had not the strength of soul, i.e. the courage, to go through with it. No character in The Death of Ivan Ilyich commits or even contemplates suicide, reflecting the weakness of the character Tolstoy attributed to most members of the middle class.

The fourth and final means of escape is also the most pitiful and painful. It is that taken by those who are aware of life’s meaningless, and who know that death if preferable, but who do not have the will to act on it by committing suicide. Nor can they fully distract themselves, being all too aware of the problem, but instead drag out their lives in a state of hopelessness, waiting for death. Tolstoy put himself in this category of people, and it is clear that Ivan Ilyich is also among them after his illness pulls him out of his Epicurean distraction:

“Ivan Ilyich was left alone with the consciousness that his life was poisoned and was poisoning the lives of others, and that this poison did not weaken but penetrated more and more deeply into his whole being. With this consciousness, and with physical pain besides the terror, he must go to bed, often to lie awake the greater part of the night. Next morning he had to get up again, dress, go to the law courts, speak, and write; or if he did not go out, spend at home those twenty-four hours a day each of which was torture. And he had to live thus all alone on the brink of an abyss, with no one who understood or pitied him”.

These four ways of living were the only options that Tolstoy observed among those people. There were those who were unaware of the problem, those who distracted themselves from it, those who acknowledged it and rid themselves of it through suicide, and finally those who knew of it but could do nothing but exist beneath its shadow it in a profound depression. To live in this last way was unacceptable to Tolstoy, but it seemed inevitable until he began to search elsewhere for an answer:

“I looked around at the huge masses of simple people, living and dead, who were neither learned nor wealthy, and I saw something quite different. I saw that all of these millions of people who have lived and still live did not fall into my category… It turned out that all of humanity had some kind of knowledge of the meaning of life which I had overlooked and held in contempt.. As presented by the learned and the wise, rational knowledge denies the meaning of life, but the huge masses of people acknowledge meaning through irrational knowledge. And this irrational knowledge is faith, the one thing that I could not accept. This involves the God who is both one and three, the creation in six days, devils, angels and everything else that I could not accept without taking leave of my senses”.

It was only when he removed himself from the intellectual, wealthy but ultimately fatuous circles in which he had previously lived and worked that Tolstoy realised there was an alternative answer to his problem. The four means of escape that he had observed were only the sole options if death did truly make life meaningless. Nihilism was the unrivalled perspective held by Tolstoy’s rationality-obsessed peers, explaining why all those the writer knew fell into one of the categories he outlined. In interacting with the Russian peasantry, however, he found that the majority of people did not see life as meaningless. Even if they did or could not understand it, they had a firm belief that human existence had some point. Their faith in a higher power gave them both meaning and a moral code by which to live. This is expressed in The Death of Ivan Ilyich through the character of Gerasim, the family servant. Gerasim first appears after his master’s death, when Peter Ivanovich is leaving the house.

“Well, friend Gerasim,” said Peter Ivanovich, so as to say something. “It’s a sad affair, isn’t it?”

“It’s God will. We shall all come to it someday,” said Gerasim, displaying his teeth—the even white teeth of a healthy peasant—and, like a man in the thick of urgent work, he briskly opened the front door, called the coachman, helped Peter Ivanovich into the sledge, and sprang back to the porch as if in readiness for what he had to do next”.

As Ivan Ilyich’s health declines, Gerasim is his sole source of comfort. He admires his vitality and cheerful constitution and enjoys talking to him. Tolstoy does not, however, offer his readers a dialogue between master and servant. The direct speech they exchange is largely concerned with simple tasks or with Ivan Ilyich’s comfort, and no profound theological ideas ever escape Gerasim’s lips. Just as Tolstoy, “listening to an illiterate peasant, a pilgrim, talking about God, faith, life, and salvation,… began to understand the truth”, so to does Ivan Ilyich’s fear of death diminishes when he is in Gerasim’s company. This is in direct contrast to the doctors who attend him. “Gerasim alone did not lie; everything showed that he alone understood the facts of the case and did not consider it necessary to disguise them, but simply felt sorry for his emaciated and enfeebled master”, whereas the doctors called to treat him are scornful, patronising and false. Upon hearing from Ivan Ilyich’s wife how the patient found relief when his servant held up his legs, “the doctor smiled with a contemptuous affability that said, “What’s to be done? These sick people do have foolish fancies of that kind, but we must forgive them”. Again Tolstoy unfavourably compares the respected intellect, whose complex ideas and extensive learning come to nothing, against the peasant, whose simple ways are healthy and effective, even if they cannot be theorised and rationalised.

After months of suffering, questioning and exploring, both internal and external, Tolstoy concluded that “to know God and to live come to one and the same thing. God is life”. Although his views on Christ and the Bible were far from orthodox, as detailed in What I Believe (1884), Tolstoy lived the latter half of his life as a religious man, and it was this conversion that allowed him to escape from the misery of a meaningless existence. After months of suffering, questioning and exploring, Ivan Ilyich reaches a similar verdict. Speaking to his family in his final moments, “he tried to add, “Forgive me,” but said “Forego” and waved his hand, knowing that He whose understanding mattered would understand”.

Here it is useful to look at the original words, although English translators have undoubtedly chosen apt etymological counterparts in “forgive” and “forego”. The former is a translation of прости́ть (prostít), which means “forgive” in the same sense; what is typically translated as “forego”, however, is пропусти́ть (propustít), which means ‘let go’, ‘let pass’ or ‘relinquish’. It does not have the same sense of giving up pleasures or resisting temptation as the English word “forego”, but instead suggests that Ivan Ilyich has accepted his death and is ready to pass on from the world, especially when spoken to “He whose understanding mattered”.

Straight away, Ivan Ilyich’s pain and fear are lessened. “He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death. In place of death there was light”. It is while holding the hand of his young son that Ivan enters this semi-serene state. “Vasya was the only one besides Gerasim who understood and pitied him”, and at thirteen, is probably still too young to have fully adopted all the vices of his society. At last someone besides the sickbed declares that “it is finished”. “He heard these words and repeated them in his soul. “Death is finished,” he said to himself. “It is no more!” He drew in a breath, stopped in the midst of a sigh, stretched out, and died”.

In a way, this is a happy ending. By starting the novella with the news of Ivan Ilyich death and presenting his friends and family’s reactions as insincere and self-interested, Tolstoy prepares us for a story about a callous society and a life that amounts to very little. Ivan Ilyich’s biography only reinforces this impression, and it is not until the final page that a ray of hope is offered. Tolstoy’s complex theology seems to deny life after death on an individual basis, and it is not clear whether his protagonist believes that he will ‘pass on’ into another realm, but the meaning has been found in God, and light has replaced the darkness. Tolstoy lived another forty years after his awakening, Ivan Ilyich only a few seconds; closing the book the reader cannot help but wonder why. The ending deliberately opens the floodgates for a cascade of questions about forgiveness, redemption, time and death.

Finally, it is interesting to consider why Tolstoy, who was of course perfectly able to convey his own emotional turmoil in A Confession chooses to put a physical illness at the heart of Ivan Ilyich’s struggle. It could simply be that such an illness or ailment is more explicit and relatable, allowing any reader to understand the protagonist’s fear and pain. Ivan Ilyich’s physical decline describes certainly serves as a powerful illustration of his destructive lifestyle, his broken body mirroring his broken soul. The ambiguity of his illness and its strange origins, seemingly triggered by the minor fall, might even cause us to question whether there is a physical pathology at all.

More than a matter of literary symbolism, could the affliction be a somatisation of his meaningless and pernicious way of living? After all, his symptoms seem to correspond in intensity with his emotional state: they “seemed to have acquired a new and more serious significance from the doctor’s dubious remarks”; it “seemed to him that he felt better while Gerasim held his legs up”; and after his final revelation, he notices the pain only when “he turned his attention to it”. But ultimately it does not matter what particular illness Ivan Ilyich suffered, or whether indeed there was a medical pathology at all, as it is his engagement with his affliction, and more importantly with death, that contains the novel’s most important message. His death casts an unfavourable light on the lives of those around him, and on all those who choose to respond to the perceived meaningless of life with hedonism, falsehood and self-interest.

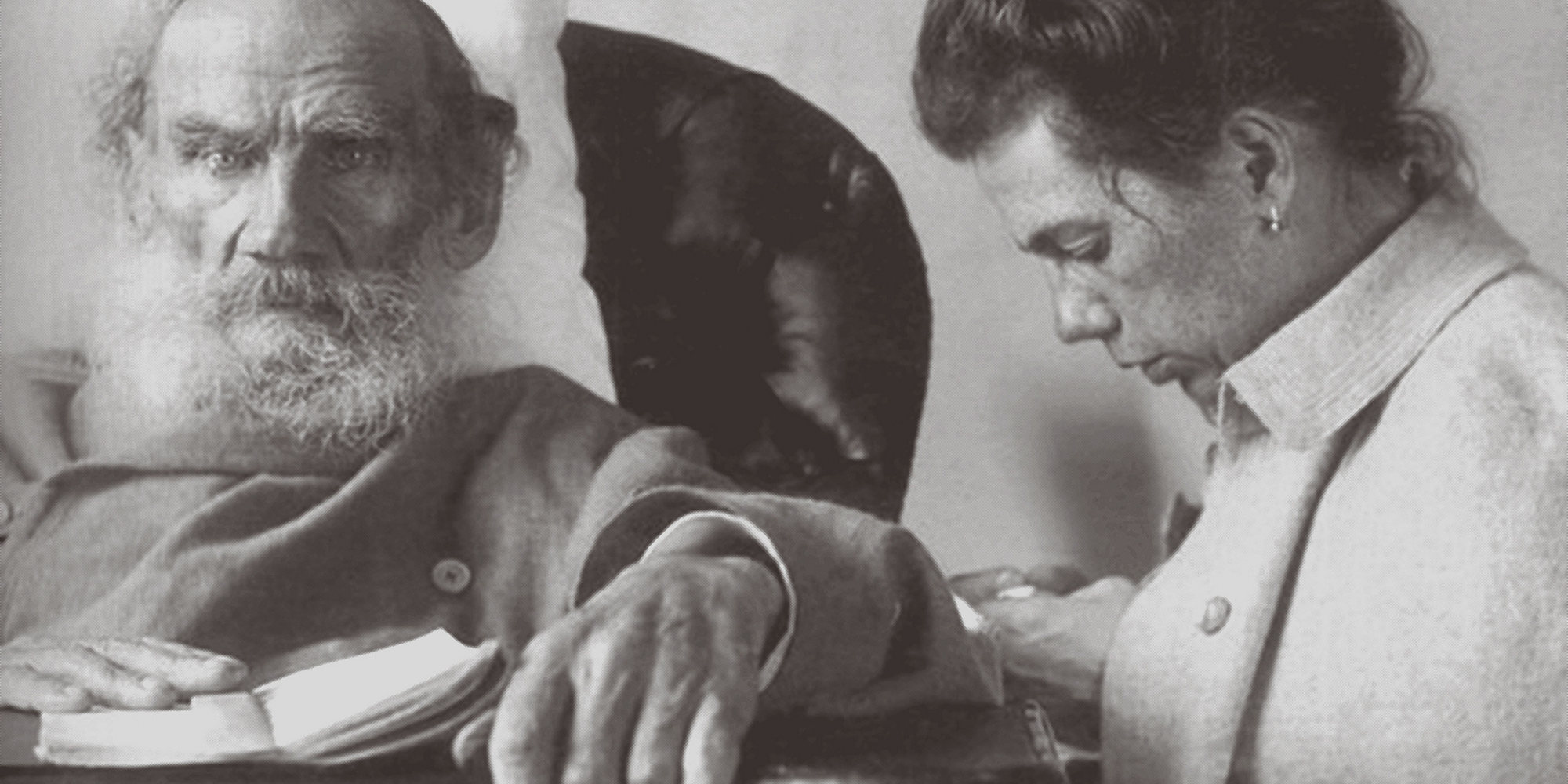

Image: Leo Tolstoy with daughter Tatyana in Gaspra on the Crimea, 1902.

Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article