Janet Brown looks at The Descent of Man

On the 150th anniversary of its publication, Janet Browne looks at the initial controversy over Charles Darwin’s ‘The Descent of Man’ and its subsequent political consequences

One hundred and fifty years ago, on 24 February 1871, the first edition of Charles Darwin’s Descent of Man was published in London. It shocked many readers. While there had been years of controversy about the origins of mankind, much of it generated by vigorous responses to Darwin’s earlier book On the Origin of Species (1859), this was the book in which Darwin unambiguously spoke his mind about human evolution. In it he described what he knew about the emergence of humans from animal ancestors, the physical characteristics of different peoples, the development of language and the moral sense, the relations between the sexes in animals and in humans, and a host of similar topics that blurred the boundaries between ourselves and the animal world. It was a big serious book that would hardly have stirred the Victorian intellectual world if it had been about sponges or orchids. But to describe human beings—Queen Victoria, Ulysses S. Grant, Dante Gabriel Rossetti— as little more than grown-up animals was dynamite.

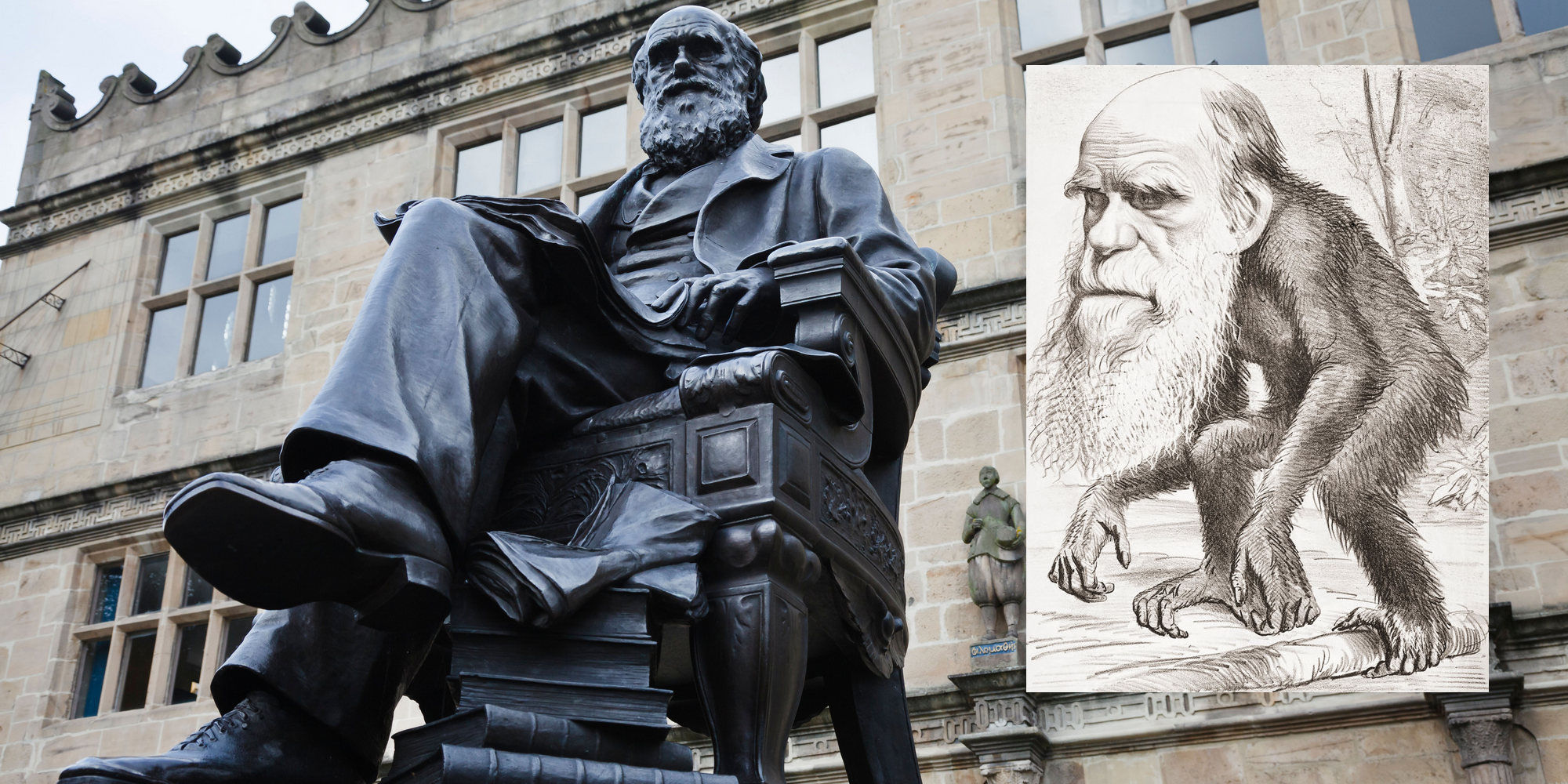

The pushback was immediate. Harper’s Weekly complained that, “Mr Darwin insists on presenting Jocko as almost one of ourselves.” The Truth Seeker called the book “hasty” and “fanciful.” The London Times deplored the book’s publication, saying “To put [these views] forward on such incomplete evidence, such cursory investigation, such hypothetical arguments as we have exposed, is more than unscientific—it is reckless.” A correspondent in The Guardian appealed directly to the Bible. “Holy Scripture plainly regards man’s creation as a totally distinct class of operations from that of lower beings.” In satirical journals of the day, amusing cartoons lampooned Darwin as an ape himself. “’A Venerable Orang-Outang. A Contribution to Unnatural History” was the caption to a hairy Darwin in The Hornet on 22 March 1871.

Others, nevertheless, welcomed Darwin’s depth of learning, sincerity, and rationality. In an article on “Darwinism and Divinity” published a year later, Leslie Stephen –the public intellectual and father of the novelist Virginia Woolf– spoke for many of the coming generations by asking “What possible difference can it make to me whether I am sprung from an ape or an angel?” In Stephen’s eyes, the Descent of Man expressed an important new feeling that science was the place to look for answers about human origins. Over the subsequent century and a half, the intellectual world has more or less come to agree with Stephen. Biologists today consider our animal origins as well-established facts, supported by fossil remains, genetic similarities, and many other features.

What was in this book that seemed so provocative to Victorians? It was printed in two volumes and published by John Murray, the London firm that had previously published the Origin of Species. Unlike Origin which has proven to be a classic text that transcends its time and place, Descent was deeply embedded in the Victorian social and moral context. Darwin began by relating the many incontrovertible anatomical features common to both animals and mankind. Then he turned to the mental powers, stating decisively, “there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties” (Descent 1: 66). He daringly proposed that religious belief was nothing more than a primitive urge to bestow an external cause on otherwise inexplicable natural events, comparing it to the “love of a dog for its master.” From religion, it was but a small step to the moral world. The phenomena of duty, self-sacrifice, virtue, altruism, and humanitarianism were, he thought, acquired fairly late in human history and not equally by all tribes or groups. Some societies displayed these qualities more than others, he noted; and it is clear that he thought there had been a progressive advance of moral sentiment from what he called the early “barbaric” societies, such as Ancient Greece or Rome, to the civilized world of 19th century England that he inhabited. In this manner, he kept the values of the English middling classes to the front of the minds of his readers as representative of all that was best in nineteenth-century culture. The higher moral virtues were, for him, self-evidently the values of his own class and nation.

Also in Part 1 Darwin discussed possible intermediaries between ape and human, and mapped out (in words) a provisional family tree, in which he took information mostly from fellow evolutionists like Ernst Haeckel and Thomas Henry Huxley. In truth, Darwin found it difficult to give an actual evolutionary tree to humans. Although there were, by then, a few fragments of Neanderthal skulls available for study in European museums, these had not yet been conclusively confirmed as from ancestral humans. For the second edition of Descent of Man he asked Huxley to fill this gap with an up-to-date essay about fossil finds. Darwin could only guess at possible reasons for human ancestral forms to have abandoned the trees, lost their hairy covering, and become bipedal.

Part II covered Darwin’s idea of sexual selection which is today understood today as a feature of animal courtship and mating behaviour. It seems curious that such a large part of the book was dedicated to a lengthy exegesis of this form of selection in birds, insects, and animals. Yet Darwin claimed its importance lay in being a powerful factor in the diversification of human beings into what were then considered to be separate races. Sexual selection was “the most powerful means of changing the races of man that I know.”

It was an idea he had been nurturing for many decades. He proposed that all animals, including humans, possess many trifling features that are developed and remain in a population solely because they contribute to reproductive success. These features were inheritable (as Darwin understood it) but carried no direct adaptive or survival value. The textbook example is the male peacock that develops large tail feathers to enhance its chances in the mating game even though the same feathers actively impede its ability to escape from predators. The female peahen, argued Darwin, is attracted to large showy feathers, and if she can, will choose the most glamorous mate and thereby pass his characteristics on to the next generation. It was a system, he stressed, that depended on individual choice rather than survival value.

In humans, he claimed physical differences between groups were similarly caused by sexual selection. Preference for certain skin colours was, for him, a good example. Early men would choose women as mates according to localized ideas of beauty, he suggested. The skin colour of an entire population would gradually shift as a consequence. “The strongest and most vigorous men…would generally have been able to select the more attractive women…who would rear on average a greater number of children” (Descent 2: 368-9). Different societies would have dissimilar ideas about what constituted attractiveness and so the physical features of various groups would gradually diverge through sexual selection alone. According to Darwin, sexual selection among humans would also affect mental traits such as intelligence, maternal love, bravery, altruism, obedience, and the “ingenuity” of any given population; that is, human choice would go to work on the basic animal instincts and push them in particular directions.

Here, we see Darwin at his most Victorian. His ideas about biology were inextricably tied up in his views about human society and gender differences among human beings. Notoriously, he believed that sexual selection enhanced male superiority across the world. In early human societies, the necessities of survival, he argued, would result in men becoming physically stronger than women and that male intelligence and mental faculties would improve beyond those of women. In civilized regimes it was self-evident to him that men, because of their well-developed intellectual and entrepreneurial capacities, ruled the social order. After publication, early feminists and suffragettes bitterly attacked this doctrine, feeling that women were being naturalised by biology into a secondary, submissive role. Indeed, some medical men assumed that women’s brains were smaller than those of men and were eager to adopt Darwin’s suggestion that women were altogether less evolutionarily developed. For many, it seemed at that time, that the ‘natural’ function of women was to reproduce, not to think.

Darwin also attempted to explain the racial hierarchy of the British empire. Notably he used Herbert Spencer’s terminology of “the survival of the fittest” that he had at first been reluctant to adopt. As he saw it, the various tribes of mankind had emerged through competition, selection, and conquest. Those tribes with little or no culture (as determined by Europeans) were likely to be overrun by bolder or more sophisticated populations. “All that we know about savages . . . show that from the remotest times successful tribes have supplanted other tribes” (Descent 1: 160). Darwin was convinced that many of the peoples he called primitive would eventually be overrun and destroyed by more advanced races such as Europeans: particularly the Tasmanian, Australian, and New Zealand aborigines. This was a playing out of the great law of “the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.” His emphasis cast the notion of race into biologically determinist terms, reinforcing contemporary ideas of an inbuilt racial hierarchy.

Such words merged easily into contemporary ideologies of empire. The concept of natural selection as applied to mankind in Descent of Man seemed to vindicate continuing contests for territory and the subjugation of indigenous populations. Formulated in this way, Darwin’s concept of natural selection was a clear echo of the competitive, industrialised nation in which he lived. It comes as no surprise that his views seemed to substantiate the leading political and economic commitments of his day. Indeed, his book can be seen as a primary motor for social Darwinism during the fifty years from 1880 to 1930 or so. These ideas were put into action by the businessmen, philanthropists and business magnates who masterminded the development of North American industry.

The political consequences of Darwin’s Descent of Man continued. Many of Darwin’s remarks captured anxieties that were soon made manifest in the eugenics movement. His cousin Francis Galton had little hesitation in applying Darwin’s ideas to establish the eugenics movement. Believing that human populations could direct their own future through selective breeding, Galton campaigned tirelessly to reduce breeding rates among what he categorised as the poorer, irresponsible, sick, and profligate elements of society, and that the ‘more highly-gifted men’ should have children and pass their attributes on to the next generation. Galton did not promote incarceration or sterilisation as ultimately adopted by the United States and elsewhere during the early years of the 20th century, nor did he conceive of the possibility of the whole-scale extermination of an entire people, as played out during World War II. But he was a prominent advocate of taking human development into our own hands and the necessity of counteracting the likely deterioration of the human race. History shows that Descent was a highly significant factor in the emergence of social Darwinism and eugenics.

So, in its way, Darwin’s Descent of Man can be regarded as a text for the times as well as the missing half of the Origin of Species–the half that Darwin delayed for twelve years because it applied the new ideas of competition and selection to humankind and human society. It gave scientific validity to common ideas in Victorian society and while it can hardly account for all the racial stereotyping, nationalist fervour and harshly expressed prejudice found in the years following publication there can be no denying its impact in providing biological backing for notions of racial superiority, gendered typologies and class distinctions.

Yet it remains a book to celebrate with interest. Thinking about the Descent of Man as a historical document allows insight not only into Darwin’s mind but also into the times in which he lived, very different from today. His conclusions were simultaneously honest and bold: “we must acknowledge, as it seems to me, that man, with all his noble qualities .. . . still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.” (Descent 2: 404)

Janet Brown is Aramont Professor in the History of Science, Harvard University and the author of the prize-winning biography, Charles Darwin: Voyaging and Charles Darwin: The Power of Place.

Images: Statue of Charles Darwin outside Shrewsbury public library (formerly Shrewsbury School where he was educated). Credit: Robin Weaver / Alamy Stock Photo

Inset: Darwin portrayed as an ape in a cartoon in the Hornet magazine of 22 March 1871. Credit: Classic Image / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article