Steven Carver looks at The Island of Dr. Moreau

‘Are we not Men?’ – Evolution and Degeneration on ‘The Island of Dr. Moreau‘

Although Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) sent shockwaves through the Victorian scientific and religious establishments (until then unproblematically linked), the book’s conclusion is remarkably optimistic:

…from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Life on Earth and, by implication, humankind, is always evolving upwards, towards perfection. This was not a view shared by the visionary British author H.G. Wells (1866–1946), who explored the theory of Natural Selection in both his fiction and his nonfiction, arriving at a somewhat bleaker conclusion. In his breakthrough novel, The Time Machine (1895), the unnamed traveller finds in his hoped-for Utopian future a human race in which ‘The too-perfect security of the Overworlders had led them to a slow movement of degeneration, to a general dwindling in size, strength, and intelligence.’ In The War of The Worlds (1898), meanwhile, the highly advanced Martians were possessed of ‘intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic’, soulless, sadistic and without compassion, much like the psychopathic Invisible Man (1897) who preceded them. And before these iconic novels, Wells wrote his most controversial parable upon the subject: The Island of Dr. Moreau.

While not as well-known nowadays as its more famous companions – although equally best-selling at the time – The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) is no less philosophically deep. It is also, like the other novels, a page-turning adventure with a crisp and vivid style giving it a strikingly contemporary sense of narrative pace. As a ‘scientific romance’, it stands on the shoulders of Frankenstein while engaging with the key scientific debates of its own day. And like all the best science fiction, it anticipates breakthroughs in human knowledge that were at best speculative but which in our own time are present and prescient. Wells always had an uncanny gift for predicting ‘things to come…’

Like much of Well’s fiction, the premise of The Island of Dr. Moreau was an extension of his scientific journalism. In 1895, the year of The Time Machine, Wells had also written a short essay entitled ‘The Limits of Individual Plasticity’ in which he speculated that the physical form of a living creature could be surgically or chemically altered, although these changes would not be passed onto its offspring as the genetic blueprint would remain unchanged. This piece reflected contemporary advances in plastic surgery and the ongoing debate concerning the ethics of vivisection. In the novel, this idea becomes reality as mad scientist Moreau carves beasts into men: ‘to the study of the plasticity of living forms – my life has been devoted,’ he tells Prendick, the story’s protagonist. Although Wells was a prolific writer across genres throughout his long life, The Island of Dr. Moreau belongs to a period of particularly remarkable creative production in which he became, in the words of his disciple Brian Aldiss, ‘the Shakespeare of science fiction’. Between 1895 and 1901, Wells defined the genre with The Time Machine, Dr. Moreau, The Invisible Man, The War of the Worlds, The Sleeper Awakes, and The First Men in the Moon. He also found time for The Wonderful Visit, a fantasy about an angel visiting contemporary England; The Wheels of Chance, a comic novel about cycling in the manner of his friend Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat; and the semi-autobiographical ‘coming-of-age’ novel Love and Mr Lewisham.

The Island of Dr. Moreau is presented as a found manuscript, introduced by the author’s nephew and heir (a framing device later pinched by Edgar Rice Burroughs in A Princess of Mars, 1911), being the unpublished account of the ‘lost year’ of his late uncle Edward Prendick, between his shipwreck at the beginning of 1887 and his rescue in January 1888. Prendick, we are told, had always claimed to have no recollection of what occurred between the wreck of the Lady Vain and being picked up a year later in an open boat belonging to another lost ship, the Ipecacuanha; although when he was found he had initially given ‘such a strange account of himself that he was supposed demented’. The editor then teases us by noting that although the Royal Navy visited what may have been Prendick’s mysterious island and found nothing, other odds and ends of maritime evidence perfectly tally with the account, introducing a frisson of gothic uncertainty to the narrative: is what follows the ravings of a man driven mad by shipwreck and isolation, or did it really happen to him? The first-person account brings a sense of immediacy and authenticity to the narrative, the protagonist frequently apologising for his lack of literary finesse. (He also has a notable ‘crutch’ word – ‘grotesque’ – which is used 16 times to describe the inhabitants of Moreau’s island.) The narrative follows Wells’ preferred method of fantastic composition, that such a story should have only one extraordinary element. This he explained in his introduction to his collected works in 1934:

As soon as the magic trick has been done the whole business of the fantasy writer is to keep everything else human and real. Touches of prosaic detail are imperative and a rigorous adherence to the hypothesis. Any extra fantasy outside the cardinal assumption immediately gives a touch of irresponsible silliness to the invention.

Science fiction readers and writers call this ‘Wells’ Law’, and it’s well worth remembering if you aspire to write in this genre. Admirer Joseph Conrad dubbed him: ‘O Realist of the Fantastic!’

When the Lady Vain strikes a derelict ten days out of Peru, the English traveller Prendick finds himself in an open boat with two sailors and very little food and water. In the tradition of shipwreck stories, both real and imagined (such as the account of the loss of the whaler Essex by the first mate Owen Chase), the starving survivors end up drawing lots to see who’ll be sacrificed (eaten) to save the others. In the first of many examples of brutal Darwinism, the strongest sailor draws the short straw and refuses to accept the outcome leading to a fight that leaves Prendick alone on the boat. Near to death, he is picked up by the drunken captain of the Ipecacuanha, transporting animals to a nearby unnamed island, overseen by the seedy medical man Montgomery and his ‘grotesque’ manservant, M’ling, who is despised by the crew. Montgomery saves his life, but admits that this was ‘Just chance,’ and could easily have gone the other way:

‘Thank no one. You had the need, and I had the knowledge; and I injected and fed you much as I might have collected a specimen. I was bored and wanted something to do. If I’d been jaded that day, or hadn’t liked your face, well—it’s a curious question where you would have been now!’

Montgomery is in his own words ‘an outcast from civilisation’ because of an unspecified indiscretion in London that happened on a foggy night and involved strong drink. But Prendick is not out of the woods yet. Montgomery explains that he can’t stay on the island, but the ship’s captain refuses to let him remain onboard either, as Prendick had insulted him when trying to diffuse a fight between the uncouth drunk and the volatile Montgomery. Montgomery’s superior, a large, white-haired man, is indifferent to Prendick’s plight and he is once more cast adrift until Montgomery takes pity and rescues him for the second time. The strange man, who Prendick recognises as Moreau, a notorious vivisectionist driven out of England some years before by a media-driven moral panic, takes an interest in the new arrival when he learns he studied biology under Darwin’s champion T.H. Huxley at the Royal College of Science, as did Wells. (Also, like Wells, Prendick does not drink.) Prendick is given a hammock in a compound on the small volcanic island, but no access to the main part of the building. He observes several ‘grotesque’ native servants, who he finds disconcerting without quite knowing why, and soon becomes aware (from the screams) that Moreau is conducting cruel experiments on the animals from the Ipecacuanha. Montgomery clearly finds this distressing. To get away from the endless agonised cries of a female puma, Prendick explores the island, noting some odd, caveman-like inhabitants and then being stalked by some sort of creature that is dressed like a man but behaves like a predatory animal. Terrified that Moreau is vivisecting human beings and that he’s next, Prendick flees the compound, after which things get really weird…

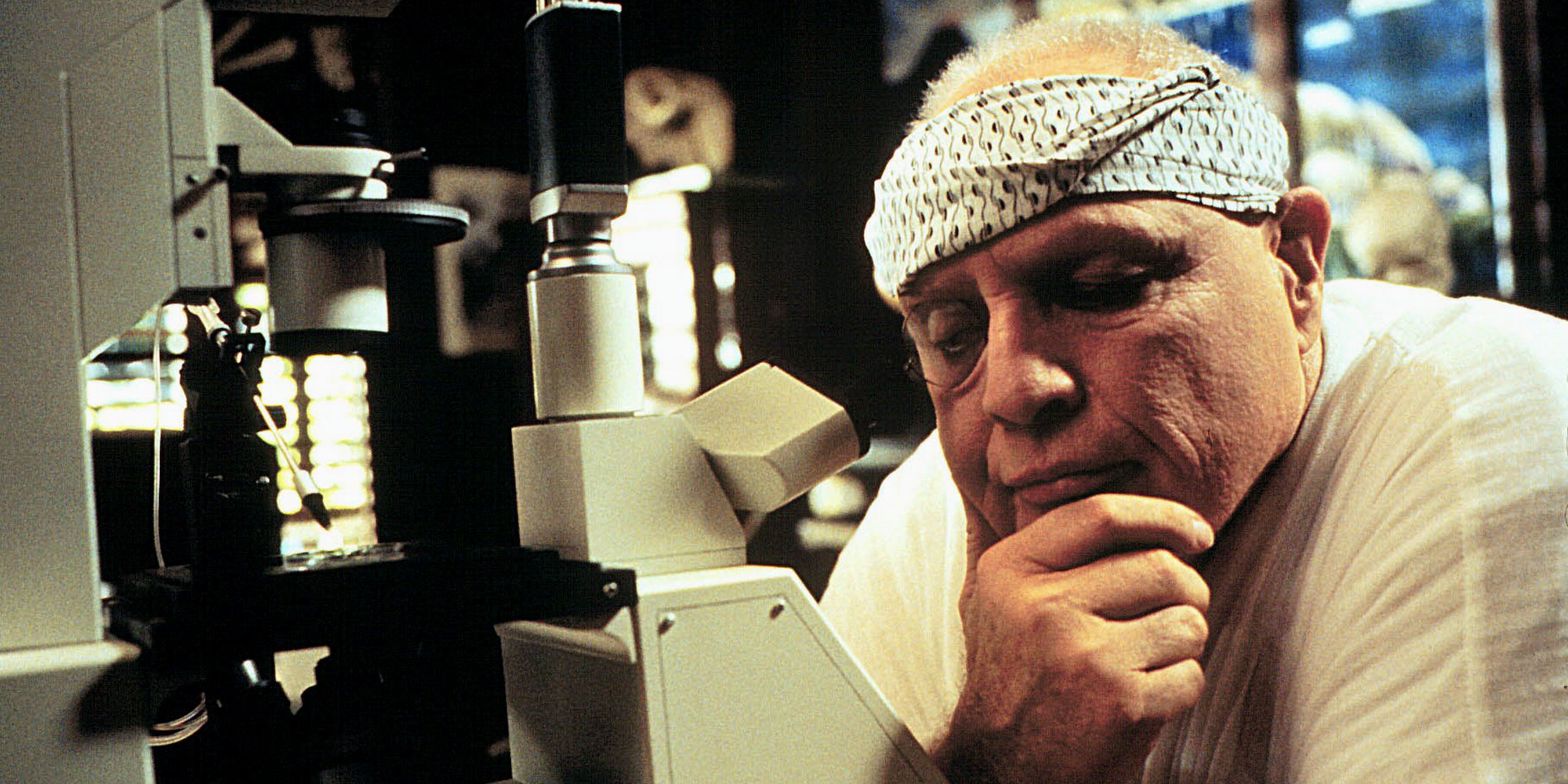

Moreau is a Victor Frankenstein figure, so obsessed with his research that he cannot see it for the abomination that it is, or that it is a path to his own destruction. As a literary character, he is the origin of the ‘uplift’ archetype in science fiction, in which animals are transformed into more intelligent beings by other intelligent beings through some sort of technological, genetic, or evolutionary intervention. He is also a construct of English anxieties about the influence of continental medicine and the campaign against experiments on live animals, the RSPCA having been around since 1824. These ideas had formally arrived in Britain in 1873 with the publication of The Handbook for the Physiological Laboratory, a medical textbook which incorporated research by the French scientist Claude Bernard, a supporter of vivisection. One of the book’s authors, the Austrian surgeon Emmanuel Klein, then at Barts Hospital in London, gave evidence before a Royal Commission in 1875 and created in the public mind the image of the sinister foreign vivisectionist. Moreau would later paraphrase him: ‘To this day I have never troubled about the ethics of the matter … The study of Nature makes a man at last as remorseless as Nature. I have gone on, not heeding anything but the question I was pursuing…’ Cool, emotionally detached and intellectual, Klein was completely indifferent to the suffering of test animals, and committee members and public alike were horrified by his admission that he rarely bothered with anaesthetic. Moreau’s ‘House of Pain’ comes straight from the work of Bernard and Klein and is a stark warning of scientific advance without moral checks and balances, without ‘humanity’. (Even his name puns on Well’s dark futurism; he is ‘Doc Tomorrow’, an ancestor of the brilliant but callous Martians.) Anticipating Conrad’s Kurtz in Heart of Darkness (whom he undoubtedly influenced), Moreau also represents the worst excesses of European colonial exploitation, unfettered by the constraints of the so-called ‘civilized’ world, recalling the atrocities of Leopold II of Belgium’s rule over the Congo Free State, which is where Conrad set his novel. (It was this connection that convinced Marlon Brando to accept the role in the 1996 film adaptation, having played ‘Colonel Kurtz’ in Apocalypse Now.) Finally, and most controversially, again like Frankenstein and his creature – who Shelley had likened to Adam confronting his maker in Paradise Lost – Moreau becomes God to his creations:

‘His is the House of Pain.

‘His is the Hand that makes.

‘His is the Hand that wounds.

‘His is the Hand that heals.’

And so on for another long series, mostly quite incomprehensible gibberish to me about Him, whoever he might be. I could have fancied it was a dream, but never before have I heard chanting in a dream.

‘His is the lightning flash,’ we sang. ‘His is the deep, salt sea.’

‘His are the stars in the sky.’

Appalled, though he is, that ‘Moreau, after animalising these men, had infected their dwarfed brains with a kind of deification of himself,’ Prendick later invokes this warped religion to save himself and Montgomery:

‘He is not dead,’ said I, in a loud voice. ‘Even now he watches us!’

This startled them. Twenty pairs of eyes regarded me.

‘The House of Pain is gone,’ said I. ‘It will come again. The Master you cannot see; yet even now he listens among you.’

Wells would later describe the novel as ‘an exercise in youthful blasphemy’, while the line ‘Do you know what it means to feel like God?’ in the pre-code Paramount production of the novel, Island of Lost Souls (1932, starring Charles Laughton as a leering, whip-cracking and messianic Moreau), got the film banned almost everywhere for decades.

There is also a hint of the ‘Imperial Gothic’ about all this, a fear of the otherness lurking at the ends of empire, in what Kipling called ‘the dark places of the earth’, which were viewed by Westerners as mysterious, barbaric, irrational, seductive and, above all, dangerous. When Prendick is pursued by a ‘Leopard-Man’, for example, Wells is almost certainly nodding towards the ‘Leopard-Man’ cannibal cult of Sierra Leone that was greatly troubling British colonial authorities at the time. Or perhaps Moreau and Montgomery have been corrupted by life in the Tropics – a common theme in Imperial Gothic fiction – although the implication in the novel is that they were like this all along as, in fact, was the rest of humanity; the first reference to cannibalism, the ultimate taboo, is after all the opening scene in the lifeboat where two white sailors fight to the death. (And we only have Prendick’s word for this as a first person and therefore unreliable narrator. When Montgomery notes bloodstains in the boat, it’s clear he’s wondering exactly how far Prendick went to survive.) As Moreau tells Prendick, ‘The place seemed waiting for me.’

This is the genius of the novel. Wells constantly interrogates evolutionary biology through his allegory, artfully blurred with Christian myth and contemporary sociology. Moreau creates the (imperfect) ‘beast-men’ and gives them a ‘Law’ to live by:

‘Not to go on all-fours; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

‘Not to suck up Drink; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

‘Not to eat Fish or Flesh; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

‘Not to claw the Bark of Trees; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

‘Not to chase other Men; that is the Law. Are we not Men?’

God, of course, did the same thing, and these legal and moral codes remain the basis for civilised society. In a more secular model of history, they evolved, like Darwin’s theory of perfection, out of the Dark Ages and into Enlightenment; either way, these codes of behaviour are the glue that holds human society together. The problem is that the ‘animalistic’ side is still there; it’s buried, in Freud’s terms ‘repressed’ – and Freud’s theories, like those of Marx, were as much of a blow to Victorian certainty as Darwin’s – but it hasn’t gone. Several times in the narrative, we are reminded that we too are just animals. At one point, Prendick lands ‘upon all-fours on the floor’ in a bit of slapstick when he falls out of his hammock, and later he feels the physical exhilaration of flight:

I saw my death before me; but I was hot and panting, with the warm blood oozing out on my face and running pleasantly through my veins. I felt more than a touch of exultation too, at having distanced my pursuers.

He also has to resist his attraction to the beast-women: ‘glancing with a transitory daring into the eyes of some lithe, white-swathed female figure, I would suddenly see (with a spasmodic revulsion) that she had slit-like pupils, or glancing down note the curving nail with which she held her shapeless wrap about her.’ (This eye for the ladies is another trait Prendick shares with his author.) This was developed in the infamous Island of Lost Souls through the seductive ‘Lota the panther woman’ who Moreau tries to breed with the hero. (See also ‘Maria’ in the 1977 film version and ‘Aissa’ in the 1996 movie, both beautiful cat-women.)

Lines between ‘Nature’ and ‘Humanity’ blur constantly. The ‘Ape-man’ Prendick meets is greatly taken with their similarities and this becomes almost a running gag in the novel: ‘He has five fingers, he is a five-man like me!’ Montgomery, meanwhile, ‘had been with them so long that he had come to regard them as almost normal human beings’; and in the end, Prendick has to become an alpha to live among the beast-men: ‘In the retrospect it is strange to remember how soon I fell in with these monsters’ ways, and gained my confidence again. I had my quarrels with them of course, and could show some of their teeth-marks still…’ Ultimately, of course, as Prendick comes to realise, the island is a microcosm of humanity and natural selection, in effect, the world:

A strange persuasion came upon me, that, save for the grossness of the line, the grotesqueness of the forms, I had here before me the whole balance of human life in miniature, the whole interplay of instinct, reason, and fate in its simplest form. The Leopard-man had happened to go under: that was all the difference. Poor brute!

And just as it is possible to advance up the evolutionary ladder, it is equally possible to slide down the snake, to move from complexity to simplicity. Moreau’s experiment – like God’s, perhaps – was always doomed to failure:

‘These creatures of mine seemed strange and uncanny to you so soon as you began to observe them; but to me, just after I make them, they seem to be indisputably human beings. It’s afterwards, as I observe them, that the persuasion fades. First one animal trait, then another, creeps to the surface and stares out at me. But I will conquer yet! Each time I dip a living creature into the bath of burning pain, I say, “This time I will burn out all the animal; this time I will make a rational creature of my own!” After all, what is ten years? Men have been a hundred thousand in the making.’

The Victorian fin-de-siècle intelligentsia were greatly concerned with theories of degeneration. As a culture that often likened itself to the Roman Empire, the British feared a similar collapse into decadence and barbarism. Degenerationists frequently saw biological change as a threat, leading down the dark path of nationalism, scientific racism and eugenics and rather missing the point of ‘hybrid vigour’. Although rejected by Darwin, degeneration became another strand of evolutionary biology and then social theory, reflecting an anxious pessimism about European civilisation’s capacity to resist decline and then downfall. As the German émigré and psychologist Fredrick Wertham later wrote of the rise of Hitler, ‘It does not take long for a society to become brutalized.’

On Moreau’s island, even with his ‘Laws’, he cannot stop this decline, and without him his creations quickly return to their bestial state entirely. History would seem to prove repeatedly that humanity is much the same. We can never truly ‘burn out all the animal’, and with the largely unregulated march of scientific discovery those lines blur even more. Wells was not the only fantastic writer to explore these themes towards the end of the century. They are present, too, in Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), She (1887) by H. Rider Haggard, and in Kipling’s short story ‘The Mark of the Beast’ (1890). And for Prendick, these anxieties follow him home. Unlike other examples of Imperial Gothic, in which there’s a very clear line drawn between life in England and those dark places of the earth, Prendick cannot now unknow what he has learned:

I could not persuade myself that the men and women I met were not also another Beast People, animals half wrought into the outward image of human souls, and that they would presently begin to revert,—to show first this bestial mark and then that … Then I look about me at my fellow-men; and I go in fear. I see faces, keen and bright; others dull or dangerous; others, unsteady, insincere,—none that have the calm authority of a reasonable soul. I feel as though the animal was surging up through them; that presently the degradation of the Islanders will be played over again on a larger scale.

Dismissed on publication by the Daily Telegraph as a ‘morbid aberration of scientific curiosity’, The Island of Dr. Moreau still has much to say. Reading it in the 21st century, after the carnage of two world wars, the proliferation of nuclear weapons (also predicted by Wells in his 1914 novel The World Set Free), genetic engineering and modification, biological weapons, and the rise, once more, of nationalism and racism on the global political stage, it is clear that this raw, disquieting and provocative exploration of what it means to be human is as relevant as ever. As the novel’s central refrain continues to ask us, ‘Are we not Men?’

Stephen Carver

Image: Marlon Brando in The Island of Dr. Moreau, the 1996 film version directed by John Frankenheimer and released by New Line Cinema.

Credit: AF archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article