Stephen Carver looks at The Phantom of the Opera

The Last Gothic Novel: Stephen Carver looks at the book behind the musical.

Now in the thirty-fifth year of its theatrical run on both sides of the Atlantic and showing no sign of stopping, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Phantom of the Opera has completely assimilated Gaston Leroux’s original character. Official accounts of the musical’s creation, therefore, downplay the cultural significance of Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (1910) as if it were a dead text waiting for the megamusical to breathe life into its corpse. In The Phantom of the Opera Companion (2007) by Lloyd Webber and Martin Knowlden, the composer describes picking up a ‘second-hand’ copy of the book, to which the corresponding Wikipedia entry adds ‘long out-of-print’. (The 1976 musical by Ken Hill, which Lloyd Webber and his producer Cameron Mackintosh knew well, is similarly reduced to a cursory reference.) In the 1991 Virgin edition of the novel – with Michael Crawford on the cover – sold at Her Majesty’s Theatre alongside the Companion, the posters, the mask, the rose, and the music box, the word Peter Haining uses repeatedly to describe Leroux’s novel in his introduction is ‘forgotten’. He also erroneously claims that the book was not particularly well-received by critics or readers on publication, describing Leroux himself as ‘a somewhat shadowy figure’ known only to the ‘keenest students of supernatural fiction’. This is an odd claim given that the author was made a Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur in 1909. Leroux, in fact, was a prolific and jobbing novelist, having retired from a colourful – and sometimes dangerous – career in journalism just before he turned forty. He wrote thirty-nine novels, many of which have been forgotten, especially outside France; Le Fantôme de l’Opéra is not one of them. The novel was serialised in France, Britain, and America to considerable acclaim, and had already been filmed twice by the time Leroux died in 1927, with a steady run of cinematic and TV adaptations continuing ever since. It has never been out of print either in French or English. Leroux’s ‘Phantom’ was a gothic icon long before the West End and Broadway got hold of him.

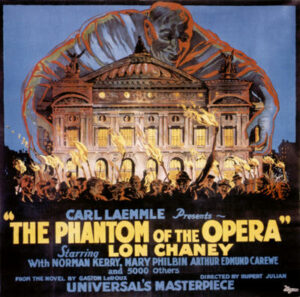

That said, it is to the original novel that Lloyd Webber describes returning in the Companion, having tried but failed to find a way to plot the story on stage after studying the two Universal film adaptations, starring Lon Chaney (1925) and Claude Rains (1943). Both films deviated from the original plot of the novel. The 1925 version added a more emphatic climax with Chaney pursued through Paris by an angry mob, while the 1943 film portrayed the Phantom as a struggling musician whose life’s work is stolen. He is then horribly scarred in the ensuing fight with the plagiarist and presumed dead, plotting his revenge from the vast network of cellars beneath the Palais Garnier and obsessing over the young soprano Christine Daaé. Relocated to London, this plot was recycled by Hammer in 1962 – Herbert Lom taking the title role – the character’s revival initiated by the ‘Phantom’ episode in the 1957 Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces starring James Cagney, reminding everyone how good the original silent movie had been. The device was then used again by Brian De Palma in his surreal 1974 rock opera Phantom of the Paradise, in which the eponymous antihero has his face destroyed by a record press. To make the story work as a musical production, Lloyd Webber wisely stripped out the revenge tragedy of the film interpretations and focused instead as what he perceived as the original ‘love triangle’ between the innocent singer Christine, her aristocratic suitor and childhood friend Viscount Raoul de Chagny, and Erik, the ‘Phantom’. In doing this, the Phantom is rewritten again, this time as a brooding romantic hero whose dangerous and undoubtedly sexual magnetism makes him considerably more attractive to most of the audience than the rather frilly Raoul, a conventional melodramatic ‘hero’ to Christine’s ‘damsel in distress and a hangover from the fairy-tale simplicity of the film narratives. While remaining broadly melodramatic, as popular musicals must be, Christine is now given a more difficult choice. This transition from villain to hero was completed in Lloyd Webber’s sequel, Love Never Dies (2010), in which the Phantom is revealed to be the real father of Christine’s son ‘Gustave’, while Raoul becomes a drunken gambler. (Meg Giry turns nasty as well.) Based on Frederick Forsyth’s novel The Phantom of Manhattan (1999), which concludes with millionaire Erik helping scarred First World War soldiers, this was clearly an attempt at full rehabilitation that went too far for fans of the original musical, and the mawkish Love Never Dies was a rare failure for Lloyd Webber. Bad boys cease to be appealing when they clean up too much. Continuing the trend to diminish the original text, Forsyth in his introduction describes Leroux’s novel as quickly ‘falling into virtual oblivion.

That said, it is to the original novel that Lloyd Webber describes returning in the Companion, having tried but failed to find a way to plot the story on stage after studying the two Universal film adaptations, starring Lon Chaney (1925) and Claude Rains (1943). Both films deviated from the original plot of the novel. The 1925 version added a more emphatic climax with Chaney pursued through Paris by an angry mob, while the 1943 film portrayed the Phantom as a struggling musician whose life’s work is stolen. He is then horribly scarred in the ensuing fight with the plagiarist and presumed dead, plotting his revenge from the vast network of cellars beneath the Palais Garnier and obsessing over the young soprano Christine Daaé. Relocated to London, this plot was recycled by Hammer in 1962 – Herbert Lom taking the title role – the character’s revival initiated by the ‘Phantom’ episode in the 1957 Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces starring James Cagney, reminding everyone how good the original silent movie had been. The device was then used again by Brian De Palma in his surreal 1974 rock opera Phantom of the Paradise, in which the eponymous antihero has his face destroyed by a record press. To make the story work as a musical production, Lloyd Webber wisely stripped out the revenge tragedy of the film interpretations and focused instead as what he perceived as the original ‘love triangle’ between the innocent singer Christine, her aristocratic suitor and childhood friend Viscount Raoul de Chagny, and Erik, the ‘Phantom’. In doing this, the Phantom is rewritten again, this time as a brooding romantic hero whose dangerous and undoubtedly sexual magnetism makes him considerably more attractive to most of the audience than the rather frilly Raoul, a conventional melodramatic ‘hero’ to Christine’s ‘damsel in distress and a hangover from the fairy-tale simplicity of the film narratives. While remaining broadly melodramatic, as popular musicals must be, Christine is now given a more difficult choice. This transition from villain to hero was completed in Lloyd Webber’s sequel, Love Never Dies (2010), in which the Phantom is revealed to be the real father of Christine’s son ‘Gustave’, while Raoul becomes a drunken gambler. (Meg Giry turns nasty as well.) Based on Frederick Forsyth’s novel The Phantom of Manhattan (1999), which concludes with millionaire Erik helping scarred First World War soldiers, this was clearly an attempt at full rehabilitation that went too far for fans of the original musical, and the mawkish Love Never Dies was a rare failure for Lloyd Webber. Bad boys cease to be appealing when they clean up too much. Continuing the trend to diminish the original text, Forsyth in his introduction describes Leroux’s novel as quickly ‘falling into virtual oblivion.

Leroux is one of those writers whose life was as interesting as his novels, and many of his own adventures as a foreign correspondent ended up in his fiction. Leroux’s family came from Normandy, though he was born in Paris after his mother went into labour on a train. His father – who claimed to be a direct descendant of William the Conqueror – sent his son to Paris to study law in 1889. This was an occupation that held little interest for Leroux, and he spent much of his time writing poems and short stories. He managed to pass the bar but then his father died suddenly leaving him an estate worth close to a million Francs. He breezed through the lot in under a year. Facing bankruptcy, he took a job as a court reporter and theatre critic for L’Écho de Paris. Combining both roles to make the court reporting less boring, Leroux started trying to solve the cases in advance of the verdicts, interviewing prisoners and in one case finding evidence exonerating the accused, humiliating the Prefect of Police, and getting a prison governor fired. ‘Curiously,’ he later noted in an interview, ‘it was my newspaper colleagues who were the most annoyed.’ Despite breaking the unwritten rule of journalism and becoming the story himself, Leroux’s reputation was now ensured, and he built on this through a talent for getting exclusive interviews with prominent public figures at home and abroad. And if he couldn’t get the interview – which happened when he blagged his way into the office of the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joseph Chamberlain, during the Second Boer War – he wrote a column on how he didn’t get the interview. This popular notoriety led to a post on Le Matin as an international correspondent, and assignments in Scandinavia, Russia (he was present during the 1905 Revolution), Morocco and Egypt (where he travelled disguised as an Arab), Africa, and across Western Europe.

By 1907, Leroux had become exhausted by travel. He abandoned journalism for fiction and achieved notable success with his first serial novel, Le mystère de la chambre jaune (The Mystery of the Yellow Room, 1907), which introduced the brilliant young reporter turned amateur sleuth ‘Joseph Rouletabille’. (Roule ta bille or ‘Roll your marble’ was French slang for ‘Globetrotter’, an obvious alter ego of the author). Leroux greatly admired Edgar Allan Poe and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and the influence of both can be seen in his seven Rouletabille novels. Like Sherlock Holmes, Rouletabille is fiercely intelligent and does not suffer fools gladly, especially policemen. He even has a ‘Dr Watson’ in the form of ‘Sainclair’, his companion and chronicler. Following Poe, The Mystery of the Yellow Room is an intense ‘locked-room’ murder mystery, and Leroux’s literary reputation in France is that of one of the fathers of modern detective fiction. Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, originally serialised in the daily newspaper Le Gaulois from September 1909 to January 1910, was his seventh novel.

Leroux was a big, ebullient man, larger than life in every regard. When he finished a novel, he would fire a pistol into the air and encourage his wife and children to join the celebration by throwing crockery out the window. What he would have made of the different incarnations of his ‘Phantom’ is anyone’s guess, but my instinct is that they would have caught him funny. Though there is a modicum of sympathy for ‘poor Erik’ towards the end of the novel, Leroux’s original character is a grotesque and megalomaniacal criminal lunatic, much closer to H.G. Wells’ ‘Invisible Man’ or George Du Maurier’s ‘Svengali’ than the tragic genius of Lloyd Webber’s musical. He is a monster inside and out, and while Gerard Butler’s scarring in Joel Schumacher’s overblown 2004 adaptation of the musical is so minimal he still looks better than most guys his age on a normal day, Leroux’s Erik is a ‘living corpse’ whose ‘hands smelt like death’:

‘He is extraordinarily thin and his dress-coat hangs on a skeleton frame. His eyes are so deep that you can hardly see the fixed pupils. You just see two big black holes, as in a dead man’s skull. His skin, which is stretched across his bones like a drumhead, is not white, but a nasty yellow. His nose is so little worth talking about that you can’t see it side-face; and the absence of that nose is a horrible thing to look at. All the hair he has is three or four long dark locks on his forehead and behind his ears.’

It is this look that Lon Chaney memorably captured in the 1925 film. By this time, Leroux had founded the film company Société des Cinéromans with the actor René Navarre and the playwright Arthur Bernède. This bought him into contact with Carl Laemmle, the co-founder and owner of Universal Pictures when the latter visited Paris in 1922. Legend has it that Laemmle had just been to the Palais Garnier and gushed to Leroux about the famous opera house. Never one to miss a chance, Leroux made a gift of his novel, which Laemmle read in a night. Already on the lookout for another vehicle for Lon Chaney to follow The Hunchback of Notre Dame (then under production), Laemmle snapped up the rights to The Phantom of the Opera. Universal went on to create a soundstage replica of the opera house and its vast cellars so elaborate and solid that it remained active until 2014 when it was finally dismantled, having been used in hundreds of movies and TV shows, including, unsurprisingly, the 1943 remake. As the producer who brought the European gothic to Hollywood, Laemmle had immediately understood the potential of the novel, and Chaney’s silent masterpieces inaugurated the ‘Universal Monster Cycle’ of movies that included Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Wolf-Man, and The Creature from the Black Lagoon. The Phantom of the Opera is therefore at the start of the cinematic gothic, just as it is at the end of the literary tradition.

As cinema was rapidly becoming the dominant art form of the twentieth century, the gothic discourse transferred from page to soundstage, subverting the realist film narrative just as it had the literary in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Phantom of the Opera is on the cusp of both forms. Written before the First World War, there is still a hint of the fin de siècle about Leroux’s original novel, while its setting is the nineteenth century, about ten years into the French Third Republic, around 1880. This makes the story broadly contemporaneous with late-Victorian English gothic fiction, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde having been published in 1886, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1891, and Dracula and The Invisible Man in 1897. George Du Maurier’s bestselling novel Trilby, meanwhile, in which a young woman falls under the influence of the sinister mesmerist ‘Svengali’ in Paris, becoming a great but ultimately doomed singer, had been serialised in 1894. The following year, Freud published his Studies in Hysteria, and Nina Auerbach has written a ‘key tableau of the nineties’ involving older men ‘leaning over female bodies: Svengali, Dracula, and Freud.’ The 1890s also saw literary fiction exploring similar themes of appropriation and fetishism of the model by the artist, the performer by the mentor, in The Tragic Muse by Henry James (1890), and ‘The Muse’s Tragedy’ by Edith Wharton (1899); the common feature running between gothic fantasy and literary realism being the erotic relationship between the dominant figure and the submissive. (George Bernard Shaw would follow Leroux in 1913 with another spin on this dynamic in Pygmalion.) Leroux is certainly tapping this vein in The Phantom of the Opera and pushing it to the extremes of sadomasochism with an almost ghoulish delight. His novel is both emotionally and physically violent, the horror then frequently offset by gallows humour. The author, meanwhile, presents himself as a ‘historian’ although his gleefully morbid delivery foreshadows the campy American ‘horror hosts’ of the 1940s and 50s, such as ‘Raymond’ in the Inner Sanctum Mysteries radio show and the ‘Crypt Keeper’ in EC’s infamous Tales from the Crypt comics. Like these characters, there is a touch of the sideshow barker about Leroux’s narrative voice, which perfectly suits the carnivalesque mood of his novel.

And, like Lon Chaney, Leroux is also following Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), both novels taking the fairy-tale premise of de Villeneuve’s La Belle et la Bête (1740) to fatal extremes. (Christine at one point introduces Raoul as ‘Prince Charming’.) There are also mythic undertones, and Orpheus and Eurydice are obvious symbols. Erik is a Hades figure, if not Satan himself; as Christine tells Raoul, ‘everything that is underground belongs to him!’ It is also notable that the operas performed during the story are Verdi’s Otello, foregrounding murderous sexual jealousy, and Charles Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette – the ‘star crossed lovers’ –and Faust. Christine has made a devil’s bargain with her secret mentor, first the ‘Angel of Music’, later the ‘demon’, and he has come to claim his due…

The novel is framed by a prologue ‘In which the author of this singular work informs the reader how he acquired the certainty that the Opera Ghost really existed.’ This is a wonderful fictional ‘hook’ on which to snag the reader’s attention and hold it: he pretends it’s all real. And this is not such a leap for his readers, the labyrinthine cellars – built to house huge painted backdrops, props, costumes, and even a stable (there really is a lake under there as well) – having by then inspired a couple of generations of superstitious opera-goers and employees to circulate ghost stories. Leroux the journalist – the ‘historian’ – then documents his research process, beginning at the ‘archives of the National Academy of music’ and supplemented by The Memoirs of a Manager by ‘Armand Moncharmin’ (who along with ‘Firmin Richard’ take over management of the theatre at the start of the story). On reading various accounts of the ‘Opera Ghost’ from thirty years before, the straight-faced Leroux claims to have become convinced this legendary figure must have been connected in some way with the mysterious death of Comte Philippe de Chagny and the disappearance of his brother Raoul along with the singer Christine Daaé. It was assumed by investigators at the time, we are told, that the brothers quarrelled over the girl and that Raoul murdered Philipe. A friend of the family urges Leroux to keep digging, assuring him that the brothers would never hurt each other. The plot thickens when a body is discovered in the bowels of the opera. This is dismissed by authorities as ‘a victim of the Commune’ (the opera house, then still under construction, had been used as a garrison and then prison during the Siege of Paris and the Paris Commune of 1870). Leroux, however, is sure this is his ‘Phantom’. He tracks down the examining magistrate in the ‘Chagny Case’, and through him finds an elderly Arab known only as ‘The Persian’ who furnishes him with various documents, including the letters of Christine Daaé, which Leroux authenticates by comparing the handwriting with papers held in the archives. ‘The Persian’ also offers his own statement, dismissed at the time as a fantasy, and ‘reprinted’ in full as ‘The Persian’s Narrative’, which takes over the novel entirely from Chapter XXI to Chapter XXV. (Artfully covering his tracks, Leroux notes that ‘The Persian’ died shortly after their interview.) The author also cites various other sources of information, including retired police officers, architects, historians, and former opera employees, several of whom are quoted in the main body of the narrative. The novel proper then begins, with the murder of the chief scene shifter. After seeing the ‘ghost’ and giving an account of his appearance, Joseph Buquet is found hanging in the third cellar ‘between a farm-house and a scene from the Roi de Lahore’, an ill omen that prefaces the tragedy to follow and the first of many references to the artifice of the opera and Erik’s subterranean ‘empire’. A balancing epilogue concludes the novel with a biography of Erik, pieced together from Leroux’s ‘research’. The fake veracity of the story is further enhanced by an appended ‘Publisher’s Note’ on the history of the Paris opera house in relation to Leroux’s story. As with the operatic intertexts, and the opera house itself, the prologue is another aspect of performance in the novel.

As Leroux was first and foremost an author of detective fiction, The Phantom of the Opera is introduced as a mystery to be solved, an answer to the questions:

1. What really happened to Christine and the Chagny brothers – who really killed Philipe, and why?

2. What is the true story behind the ‘Opera Ghost’, the bones unearthed in the cellar?

3. How are these two sets of people related?

The reader knows the end before they begin; two people are dead, and two are missing. What is not known is how and why this happened. Because this is such an iconic text, we already have a good idea of the answers, even if we’ve never read the original novel. The same is true of Frankenstein, Dracula and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which are similarly fragmented narratives made up of different accounts and pieces of quoted evidence that are so culturally endemic it’s impossible not to know the stories. But in 1910, nobody knew these answers. In reading, we must try to recapture this contemporary innocence and enjoy the revelation of the narrative. And when returning to the source of familiar literary characters like these, one will always be surprised and delighted by what one finds there. The movies are never the same.

The other form of narrative that deploys fragmented text is the Gothic. The gothic anti-novel thrives on multiple points of view and conflicting ‘evidence’ to undermine the set interpretation of the realist text and thus add another dimension of unease to the reading experience, rendering it, like the story itself, uncanny. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, for example, is framed by Captain Walton’s letters to his sister, while the main body of the text is Victor Frankenstein’s confession, which is, in turn, annexed mid-point by the first-person narrative of his creature. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, meanwhile, offers a third-person frame plus ‘Dr Lanyon’s Narrative’ and ‘Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case’. Bram Stoker’s Dracula – which in theme and construction The Phantom of the Opera most closely resembles – is the most eclectic gothic narrative of all, comprising:

-

- Jonathan Harker’s Journal.

- Letters from Lucy Westenra to Mina Harker.

- Mina Harker’s Journal.

- Newspaper cuttings.

- A long letter from Dr. Seward to Arthur Holmwood.

- Lucy Westernra’s Diary.

- Dr Seward’s Diary.

- Professor Van Helsing’s notes, were recorded on a phonograph.

This level of narrative disintegration functions as a series of competing frames of explanation, creating a tension between natural and supernatural possibilities, like a series of witness testimonies in a complicated murder trial. Multiple points of view are also a feature of postmodern narratives, in which the unstable nature of the Self is reflected in the instability of the text, key examples being Franz Kafka’s The Trial, the early novels of Thomas Pynchon, and Samuel Beckett’s ‘Trilogy’. It could be argued that Leroux is doing something similar with The Phantom of the Opera. Although inspired by the English Gothic, the French romans noir is less interested in monsters and tends more towards psychological depth in the tradition of Poe, using the relationships between characters – and themselves – to show the fears and contradictions at the heart of the human experience. The Phantom of the Opera is therefore a tale of love and obsession, as well as an exploration of gender, identity, race, and social class. Raoul and Phillipe are aristocrats, Erik is almost comically bourgeois in his marital ambitions, while part of his otherness stems from an oriental past; Christine is proletarian and bohemian, the daughter of a failed Scandinavian musician who is spied on as much in the story by Raoul as she is the Phantom. There is also a Freudian subtext about a girl who loves the ‘Angel of Music’ she believes has been sent by her dead father, and a broken boy who lives in an underground house full of his mother’s possessions… Jung’s theory of archetypes is equally in play: the relationship between the Self (‘the totality of the psyche’), the Persona (‘a kind of mask’), and the Shadow (the ‘instinctive and irrational’). And not just Erik wears a mask; as Leroux writes in Chapter III: ‘In Paris, our lives are one masked ball.’ ‘Poor Erik’ is Persona trying to achieve unified Selfhood through love but instead becoming only a Shadow, a description used repeatedly by Leroux to emphasise his ‘ghostly’ comings and goings. As to whether he finally achieves any sort of redemption, as suggested by the musical, you’ll just have to read the book for yourself.

After the Phantom, we must look to the cinema for our gothic icons. This is not to say that the gothic novel ceased to exist, only that with Leroux’s creation the archetypal pantheon had been filled. He stands with the other giants of the genre, most of whom remain linked through those early Universal pictures. (Only Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde belonged to Paramount.) At 110-years-old and a global brand, the old ‘trapdoor lover’ is oddly looking pretty good for his age. Like Dorian Gray, he remains forever young, his story endlessly retold, re-invented, and re-imagined across media, while the actors who play him on stage periodically change like Dr Who. But that’s not his real story. That still resides in this remarkable French novel by an equally remarkable French author. The Phantom of the Opera is truly the last gothic novel and should be read and respected as such.

Main image: Lon Chaney in the 1925 Universal Pictures film version. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image in text: Poster for the same film. Credit: Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article