The ‘Strand Magazine’ – Part Two

The final part of the story of the ‘Strand Magazine’.

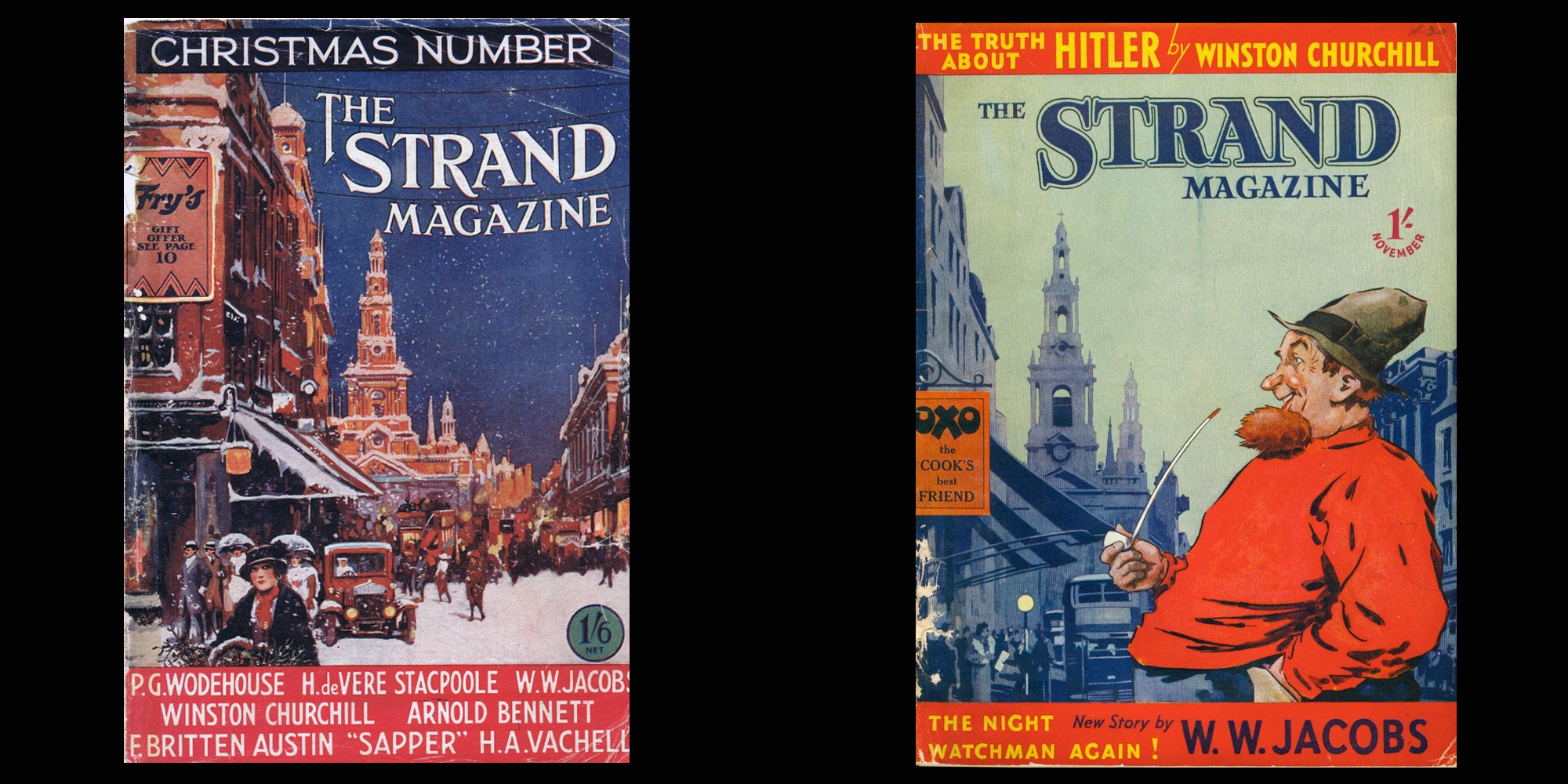

The Strand’s popularity grew alongside Conan Doyle’s, and in the ensuing years, it included in its pages the works of several other great authors. During its sixty-year history, the Strand was host to a wide array of short story fiction from writers such as W.W. Jacobs, H.G. Wells, and W. Somerset Maugham. As their names suggest, the range and variety of the stories as part of the appeal of the publication. Ghost stories rubbed shoulders with science fiction yarns, war stories and human dramas. In the dark depression days of the thirties, comic stories were particularly popular. Their facility of raising the spirits was much appreciated by readers. The antics of P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster were a comic mainstay of the magazine at this time. The amusing interludes presented by his stories, reflect an earlier apparently more charming era, where difficult aunts, marital misunderstandings and champagne headaches were the worst that one could trouble a person rather than the realities of unemployment and the threat of war.

Continuing the tradition started by Doyle, the Strand also became a source for new detective fiction from authors such as Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, E.C. Bentley, and Edgar Wallace, who wrote a new series of his Four Just Men series for the magazine, Dorothy L. Sayers, G. K. Chesterton with his Father Brown mysteries and Georges Simenon.

Factual reports from distinguished contributors were regularly featured as well. Even a monarch got in on the act. A sketch Queen Victoria had drawn of one of her children was published (with her permission) in the Strand.

Winston Churchill also contributed to its pages. Apart from many features about his life and career, he also wrote articles himself for the magazine. It was as a consequence of his colonial responsibilities that he made his first contribution. During the autumn of 1907, Churchill, who at that time was Under Secretary of State for the Colonies, travelled through British East Africa, including Kenya and Uganda, ostensibly on a hunting trip but his official duties were never far away. He chronicled his travels in My African Journey, which was serialised in The Strand in nine parts from March to November 1908. Churchill’s artistic talents were first displayed in the Christmas 1921 issue, which ran the first of a two-part piece ‘Painting as a Pastime’. It reproduced eleven of Churchill’s paintings in full colour, alongside an essay which explained how he first discovered the thrill of painting and how he developed his skills in this medium. During the twenties, he began to draft autobiographical pieces which would later form part of his first volume of autobiography, My Early Life (1930). Two of these appeared in The Strand, starting with the two-part ‘My Escape from the Boers’, in the December 1923 and January 1924 issues.

While the Strand successfully survived the First World War, it faltered seriously during the Second World War. Reading habits had changed and the audience had changed. The rise of the cinema as a temporary escape from the humdrum nature of life had become the most popular form of entertainment. The war also brought about a severe reduction in free time for all the population and thus there was less time for reading for pleasure. As a result, the demand for the particular kind of fiction provided by the Strand faded. Also during the Second World War paper was rationed, and the magazine had to be decreased in size and offered fewer pages, a change that P. G. Wodehouse, amongst other contributors, deplored. Another problem experienced by the editor, Reginald Pound, at this time was his inability to attract big names to write for the publication. Due to financial restraints, he was not able to offer large enough fees to secure the services of top-class authors. He was forced to buy stories and articles from American writers, unfamiliar names because the supply of homegrown talent was running exceedingly low.

Costs rose, circulation fell, and while the magazine staggered on in the early post-war years, the situation grew worse. By 1950, it was terminal: the Strand needed a quarter of a million pounds to put it back on its feet. The owners saw no hope of raising the money, so in March of that year, the Strand was forced to cease publication. By then the circulation had dropped to 95,000 – a far cry from the glorious 500,000 it was achieving in its heyday. There was great sadness in the publishing world and a certain amount of anger that the publishers were prepared to let the Strand die. But sadly there was no remedy to resuscitate the old war horse. The Strand had been an institution which had provided a showcase for some of the greatest storytellers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and, of course, it remains the spiritual home of Sherlock Holmes. Without the Strand, who knows if Holmes and Watson would be the well-regarded icons they are today.

Books associated with this article