Sally Minogue looks at W.B. Yeats’ Collected Poems

In the centenary year of Irish Partition, Sally Minogue looks at The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats in the light of the poet’s relationship to Irish history and identity.

Although we think of William Butler Yeats as one of the founding fathers of 20th-century poetry and a central exemplar of High Modernism, he was 35 years old and already an established poet when the 19th century turned into the 20th. The range and variety of his poetry are in part explained by a life lived half in one century and half in the next – he died in 1939 – and a relatively long writing life, from his first collection Crossways in 1889 to Last Poems in 1939. Wordsworth Editions’ Collected Poems spans this entire oeuvre, from the early mythical Irish period (from when dates Yeats’ best-known poem, ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’) to the spare, pared-down, Parnassian style of his final years.

There is so much to be said about Yeats, but here I’d like to concentrate on the motif that runs through his poetry from start to finish, that of Irish identity. We are in the centenary year of Irish Partition, a profoundly important historical moment for both Ireland and England. Partition (1921) was the process by which the six northern counties of Ulster were separated, politically and geographically, from the rest of Ireland (at that point the Irish Free State), in the culmination of the long fight for Irish independence from English rule. That process of resistance had begun as early as the 18th century through informal underground groups such as the United Irishmen. It was then formalised in the 19th century with the formation of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, whose principal aim was to dissolve the Act of Union imposed by England (1801), and to achieve a fully independent Republic of Ireland. Implicit in the movement was a belief that this would be achieved only by armed struggle. It was the IRB, enjoying a new lease of life in the early 20th century, who instigated the Easter Rising of 1916, a failed insurrection but one which led, through the execution of its leaders and their subsequent martyrdom, to the negotiation of a form of independence in the Irish Free State. In a complicated process, and one where historical accounts are much contested, the Anglo-Irish Treaty that was agreed included the partition of the six Northern counties from the rest of the island of Ireland. In 1921, Ulster became (as it remains) part of the United Kingdom, while Ireland began to move to full independence. A hundred years later we are seeing the results of that partition played out within Brexit, as the Irish border once again becomes a site of contention. When Yeats was born, Ireland was firmly under English rule. In 1922, he became a Senator of the Irish Free State with a say in the future of an independent Ireland. When he died, the Irish Free State had been replaced by the fully independent state of Ireland (1937) – an independence symbolised by the fact that it remained neutral in the Second World War (whilst Ulster was of course aligned with the United Kingdom). Yeats was in the thick of this period of historic change; we don’t often see poets in such positions.

This then was the period of ferment against which we can map Yeats’ involvement in (and sometimes distancing from) the nationalist movement. For each of the key moments in the process towards Irish independence, there are corresponding poems, and sometimes plays, written by Yeats. His first political engagement can be seen in his involvement with the Irish Revival in the late nineteenth century, where his writing embodied a heroicised Irish identity reaching back into ancient legend (The Rose and The Wind Among the Reeds). Thereafter, his poetry marks a disengagement with that mythicised ‘Romantic Ireland’ in the pre-First World War period (The Green Helmet and Responsibilities), followed by complex reflections on the 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent war of Independence with England in The Wild Swans at Coole and Michael Robartes and the Dancer. In his later collections he took a notable stance of withdrawal. In the aptly named The Tower, he looks from aloft, as it were, upon the period of Civil War waged between opposing Republican forces who disagreed about the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty which had led to the Irish Free State and Partition. In The Winding Stair and Other Poems, whilst still engaging with Irish history, he begins to develop that high poetic stance and distance, perfected in the tones of Last Poems.

Yeats’ politics always embodied contradictions. He was born, in 1865, in Dublin, into a Protestant family – Protestantism then allied to English power, since Catholic Ireland was at this time firmly under English rule. He was educated largely in England and moved between the English and Irish worlds, secure in the position of belonging to the Protestant hegemony. At the same time, his background was artistic, even bohemian, and through his writing, he became a leading figure in the Irish cultural revival. Thus far Yeats’ politics were nationalist only in a cultural and mythic sense. It was in the ferment of Irish nationalist (predominantly Catholic) politics in the early part of the 20th century that Yeats had to engage more personally with his Irish identity and politics. A catalyst in this was his falling in love with Maud Gonne, a significant figure in the nationalist movement, and the poetry that his love of her inspired engages inevitably with her politics. Gonne is often seen only through the lens of Yeats’ love for her and through the poetry that she inspired, but her role as a revolutionary in the establishment of Irish independence was arguably more significant. When Yeats accepted the role of Senator in the Irish Free State in 1922, he was implicitly taking sides on behalf of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and he continued this role until 1928 after the resolution of the Civil War.

It is an index of the controversy that inhabits Irish history that I have necessarily spent some time giving even the briefest of accounts of it; and so, somewhat belatedly, to the poems. Two of his earliest poems, ‘Down By the Salley Gardens’ (16) and ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’ (31) are also his most popular, the former by being set to music, the latter heavily anthologised. They are characteristic of his early style, influenced by the English Romantic poets, but with an Irish atmosphere or point of connection. The ‘salley’ gardens may refer to a meeting spot by the river in Sligo (the home county of his grandparents, and Yeats’ spiritual home) – ‘salley’ meaning ‘full of willows’, and the poem itself acknowledged by the poet to be based on a folk song he heard a peasant woman singing in a Sligo village. Innisfree is a real island in the middle of Lough Gill, located in Sligo, and here again Yeats glosses the poem himself, telling us that he had a sudden, homesick image of the island when walking through the streets of London. Wordsworth-like, in the midst of the city, he conjures up the rural idyll in imagination, conscious at the same time that it is more dream than reality to imagine that he might ‘live alone in the bee-loud glade’. The poem, with its ‘nine bean-rows’, its ‘lake water lapping’ and its promise of ‘peace … dropping slow’ speaks to the ideal image of a withdrawn, simple life for many.

Even in these first poems, Yeats was at work establishing an Irish frame of reference to replace the English Wordsworthian one; ‘before I was twenty’ he tells us, ‘my subject-matter became Irish’. He pursues this further in the deliberately mythicising poems in these pre-1900 collections, using Gaelic spellings for names. The titles alone give us the idea: ‘Cuchulain’s Fight With the Sea’ (Cuchulain being a legendary Irish warrior), ‘To Ireland in the Coming Times’, ‘The Hosting of the Sidhe’ (the Sidhe being Irish gods), ‘The Song of the Wandering Aengus’ (another mythical figure). We might be tempted to dismiss all this as faery nonsense, of a piece with Yeats’ Golden Dawn silliness and his belief in automatic writing. But then we need to remind ourselves that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land draws on a great deal of mythical material for which our sourcebook is J. G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough. Yeats and Eliot, Modernists both, draw strongly on myth.

As it was, Yeats quickly rejected that style of poetry (though not the myths themselves):

Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.

(‘September 1913’, pp. 86-7)

John O’Leary had been a significant figure in the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and after a period of imprisonment and exile for his agitational politics, he returned to Ireland and was part of the nationalist circles Yeats moved in, along with Maud Gonne. In ‘September 1913’, Yeats names several of Ireland’s past political heroes, apparently lamenting them, yet at the same time describing their passion as ‘all that delirium of the brave’. The implication of the poem is that there’s nothing glorious to be salvaged from the necessarily violent revolutionary politics of the present.

The neat oxymoron of ‘delirium of the brave’ encapsulates the contradictoriness of Yeats’ position in relation to nationalist politics. He is never averse to naming names, in the spirit of honouring Irish martyrs, but in the careful balance of his poetic voice as it develops and matures, he gives with one hand and takes away with the other. We might be reminded here of Seamus Heaney with his scrupulous poetic negotiation of the spaces between Catholic and Protestant: ‘Whatever you say, say nothing’. James Joyce famously flew by those nets of ‘nationality, language, religion’ (Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), but only through self-exile. As I have said, Yeats was, indeed placed himself, firmly in the midst of these things, and some of his best poems are a product of the complicated dialogue he had to conduct between poetry and politics. In the collection The Wild Swans at Coole (1919), which includes poems written during the First World War, we see only glancing reflections on that conflict, during which, after all, the Easter Rising had taken place. ‘An Irish Airman Foresees his Death’ has as its well-hidden reference points both the death of Major Robert Gregory, son of Yeats’ great friend Lady Augusta Gregory, and the fact that there were many Irishmen serving in the First World War who were fraught by the tensions of fighting for a country from whom in all other ways they were trying to get independence:

Those that I fight I do not hate

Those that I guard I do not love

(111)

The poem is so perfectly balanced that the reader has no space to insert an interpretative blade, even of the thinnest sort. The poem before it, overtly titled ‘In Memory of Major Robert Gregory’, allows for far more of the poet’s own emotion. Both are fine memorial poems. The poem that precedes them, leading the collection, is the eponymous ‘Wild Swans at Coole’. No obvious politics here, just Yeats’ masterly evocation of a landscape, and a reflection on growing old while the swans somehow remain the same:

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old

(107)

It is only as an afterthought that the reader notices that there are ‘nine-and-fifty swans’ – so one lone swan without its lifelong lover, as the poet is single, isolated, observing, his heart sore. But here he is the lesser being; the poem is dominated by ‘those brilliant creatures’ that ‘scatter wheeling in great broken rings / Upon their clamorous wings’. Like the watching poet, we are privileged to share the sight, through the poem, of the wild swans at Coole. Nothing more is needed for a great poem, as long as it is in the hands of a great poet.

In ‘On Being Asked for a War Poem’ in the same collection, Yeats avers:

I think it better that in times like these

A poet’s mouth be silent

(130)

Whatever you say, say nothing. Yeats famously backed his own view when editing the Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892-1935, ostentatiously omitting those who have since become major poets of the First World War, most notably Wilfred Owen, arguing that ‘passive suffering is not a theme for poetry’. I would argue that ‘passive suffering’ is scarcely the right description! But anyway, Yeats’ sin of omission has made for very good literary copy ever since. He was after all doing what an editor is appointed to do – edit. Cultural history has found his judgement wanting; it is one of the things that makes anthologies interesting.

Yeats might have bethought himself that he too was writing war poetry, when he engaged with the Irish uprising as a subject. His collection Michael Robartes and the Dancer (1921) contains his most remarkable political poem, ‘Easter 1916’, actually written only months after the Rising and the execution of the main participants. Once again, the poet names names – the sort of particularity one wouldn’t expect of a Modernist poet. Yet the poem rises beyond its particular historical moment, noticing the way in which ordinary men and women with venial faults can be transformed by a larger cause. At the same time, the poetic voice does not endorse that cause. The poem is held in suspension between ‘hearts with one purpose alone … / Enchanted to a stone’, and the idea that ‘Too long a sacrifice / can make a stone of the heart’. Reminding us of ‘the delirium of the brave’, the refrain ‘A terrible beauty is born’ catches both sides of a fearful equation.

Yeats’ great, unrequited love, Maud Gonne, is one of the dramatis personae in ‘Easter, 1916’, though she is not named – names are reserved for those who were executed. One of those, MacBride, was Maud Gonne’s by then estranged husband. This is a personal as well as a political poem. But in the end, it is simply a poem – and again, a great one.

Two years after this collection, in 1923, Yeats won the Nobel Prize for Literature, a fitting recognition for a great body of poetry. There is a sense in the subsequent collections of his taking on that mantle, of wearing the laurels. It is his late poems that are seen as his greatest by many, the voice stripped-down, lapidary, oracular. ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ (163) is one of the best of these. For myself, I prefer his more modest voice, as that in ‘Among Schoolchildren’ (183-5), where he recognises himself as ‘A sixty-year-old smiling public man’ but is at the same time haunted by dreams of ‘a Ledean body’ (a reference to Maud Gonne). Surrounded by schoolchildren, he is immediately transported to the image of her ‘at that age’:

And thereupon my heart is driven wild:

She stands before me as a living child.

The wonder of this poem is that it begins in an actual dusty schoolroom, flirts briefly with the love of his life, sees her as a child, imagines the pang of his own birth from the point of view of sixty years, then veers via Aristotle and Pythagoras into the nature of life, art, creativity, ending on an unanswerable question: ‘How can we know the dancer from the dance?’ How could the reader not be entranced? And luckily we do not need to answer that final question.

As I have been writing this, Seamus Heaney has been much in my mind – another Nobel Laureate. I’m sure Yeats, or more likely some lines of Yeats, would have been in his mind when he stepped off the plane to meet the bear hug of his farmer brother, soon after his Nobel Prize was announced. I don’t know where he was flying from; I saw the footage on the television news – a little plane, the brother right there on the runway as Heaney came down the steps. An image of brotherly love, celebrating a moment of Irish literary history that was also a moment of family history. I was lucky enough to hear Seamus Heaney read and talk, to be in the same space as him; Yeats’ reading I have of course experienced only through recordings. I heard them when I was an impressionable sixteen; I suppose they were on some sort of tape. But his delivery has stayed with me, and similarly it felt as though I was in the same space as him. He was reading – or perhaps rather, singing – ‘Words for Music Perhaps’, and the poem I particularly remember is ‘Mad as the Mist and Snow’. Impossible to capture the entirely unembarrassed swooping, chanting voice. I’ve never tried to rediscover it because it remains for me, as it felt then, exactly what a poet should sound like. But then, when I heard Heaney, with his conversational, unassuming delivery, I felt just the same.

The references to and quotations of Yeats’ remarks about his poems are taken from the poet’s annotations in Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats, Macmillan, London, 1971.

James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is published by Wordsworth, and my several blogs on Joyce can be found on the website.

Seamus Heaney’s collections, which I strongly commend, though they need no commendation, are published by Faber.

I think the Yeats recordings are available at the British Library – but I don’t want to track them down, lest I be disappointed.

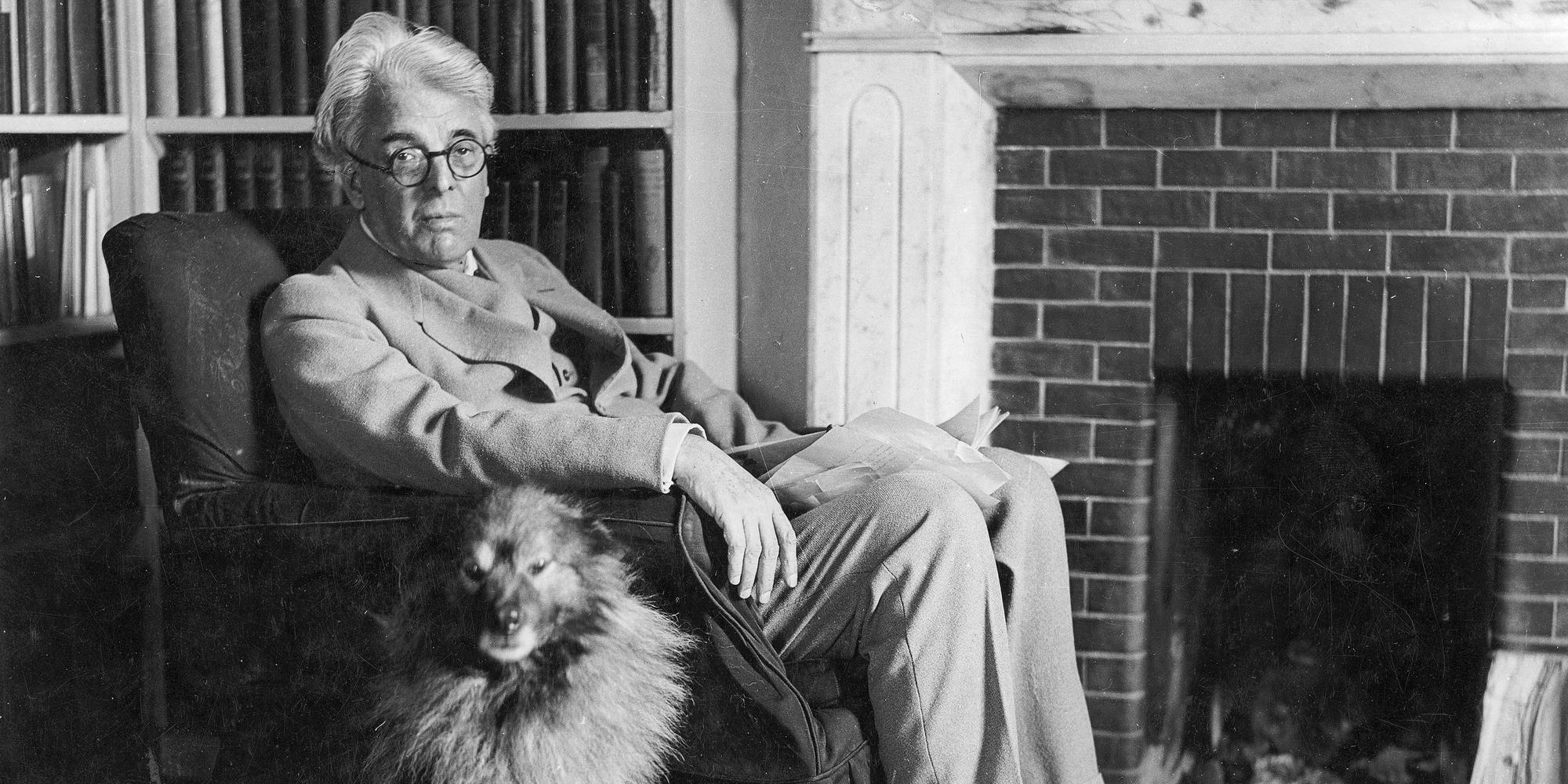

Image: William Butler Yeats (1865-1939).

Credit: Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article