Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

When I first read Pride and Prejudice as a moody fourteen-year-old, I was far from impressed. I had little interest in the characters, even less enthusiasm for the society in which they lived, and as for the preoccupation with marriage, well that just left me cold. Some of you dear readers may gasp in horror at such notions. However, my fourteen-year-old self was in good company, as Charlotte Brontë also thought Miss Austen was somewhat over-rated. In a letter to her friend, the literary critic G. H. Lewes she asked: ‘Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point.’ On the basis of Lewis’s praise, she went ahead and read Pride and Prejudice and delivered her verdict: Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

And what did I find? An accurate daguerreotyped portrait of a common-place face; a carefully-fenced, highly cultivated garden with neat borders and delicate flowers – but no glance of a bright vivid physiognomy – no open country – no fresh air – no blue hill – no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses.[1]

Ouch. In other words, Jane Austen’s style of writing is controlled, contained and ‘confined’, and one could even say, despite the sophistication of the society presented, it is a little common-place. That is, if you agree with Miss Brontë. Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

The next time I encountered Pride and Prejudice I was a mature undergraduate student and I was not all that enthused as finding this novel on my reading list. However, after reading the first chapter I experienced a shift in my earlier opinions and was impressed by how much Austen achieves in the space of just a few pages. Plus I immediately began to appreciate Austen’s humour.

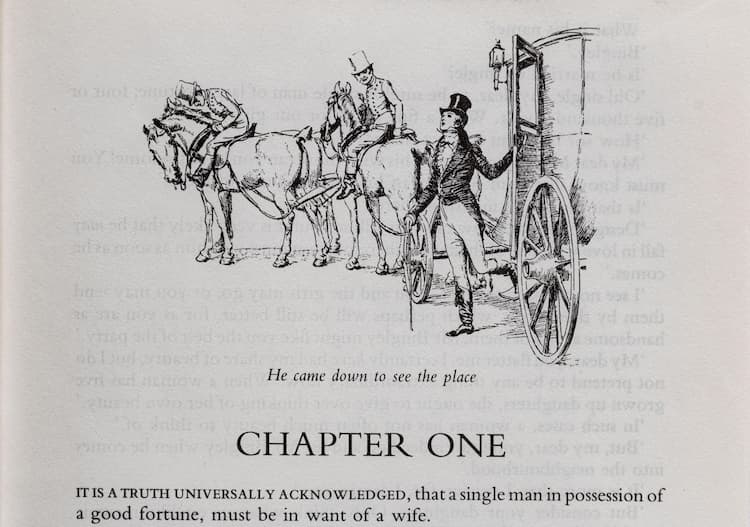

The famous first line

The opening sentence is one of the most well-known beginnings to a novel in English literary history: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.’ The narrative voice continues to explain that regardless of how much or little is known about said man, such ideas are so powerful ‘he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.’ We are then introduced to Mr and Mrs Bennet and from their ensuing dialogue on the subject of the newly arrived Mr Bingley into the neighbourhood their characters are firmly established. Mr Bennet appears quick witted and seems to enjoy using his words to toy with his wife. His response to her laying claim on Mr Bingley as a potential husband for one of their daughters is the question ‘Is that his design in settling here?’ Her lack of insight is immediately apparent as she takes his question at face value whilst the reader recognizes his sarcasm. As their exchange continues Mrs Bennet declares ‘… You take delight in vexing me. You have no compassion for my nerves.’ Her husband’s witty retort once again is not absorbed by her and is again at her expense:

‘You mistake me, my dear. I have a high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these twenty years at least.’

Thus, the first chapter establishes the social world of the novel, with its rules and traditions, it introduces some of the significant characters in a mildly humorous way, and in case the reader is in any doubt about Mrs Bennet, concludes by informing us ‘The business of her life was to get her daughters married; its solace was visiting and news.’ Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

The equally short and speedy second chapter functions to further establish familial relations within the Bennet family. The reader has already learned Elizabeth is her father’s favourite, and it becomes apparent Mrs Bennet favours Lydia as she reassures her that eligible bachelor Bingley is bound to dance with her at the forthcoming ball even though she is the youngest. She has already scolded Kitty for coughing too much as it tears her fragile nerves to pieces. Meanwhile Mary ‘wished to say something very sensible, but knew not how.’ Elizabeth soon begins to emerge as the character we are encouraged to have sympathy with.

The subsequent early chapters continue in a similarly detailed vein to introduce characters, and develop relationships and opinions which could concur with Charlotte Brontë’s rather dismissive notion Jane Austen’s style as ‘only shrewd and observant.’ Whilst her work may read like mere social observation, Austen achieves much more and offers a distinct critique of the early Nineteenth Century marriage market. At the aforementioned ball which features the first meeting between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy, it becomes apparent that men are valued by their monetary status and income, whereas women are judged by their level of prettiness. Darcy is overheard declaring Elizabeth to be ‘tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.’ Austen employs the technique of free indirect speech whereby narrative commentary adopts character opinion as we learn Darcy ‘was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world, and every body hoped that he would never come there again.’ (Chapter 3).

Pride and Prejudice initially began life as a manuscript entitled ‘First Impressions’ completed in 1797 when Austen was only 21, the same age as Elizabeth Bennet. Her father sought publication on her behalf but was unsuccessful. It was not until 1813 after further re-workings that Austen herself managed to find a publisher following the success of her first novel Sense and Sensibility. The author was merely identified as ‘a Lady’ and subsequently Pride and Prejudice entered the market under the guise as ‘by the author of Sense and Sensibility’. The novel received immediate positive reviews and there was much speculation regarding the identity of the author. Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

Early in the novel, we learn that the Bennet sisters are in a rather precarious situation. The family estate is entailed through the male line and as the family consists of five daughters, on the death of Mr Bennet the estate will pass to a distant relative, Mr Collins. Mr Bennet’s annual income is £2000, an amount which allows them to live in comfort and maintain an appearance of respectability as part of the landed gentry class. They are, however, inferior to the Bingleys, a fact which the Bingley sisters and Mr Darcy are quick to recognize. Having no male heir to succeed Mr Bennet in their immediate family, plus the added burden of providing a dowry for each of the five daughters, there is some urgency for the older Bennet girls to make a good marriage. The superior Bingley sisters make mirth that the Bennets have an uncle who makes a living as a lawyer and another who lives ‘near Cheapside.’ At Mr Bingley’s protestations regarding such snobbery Darcy merely points out ‘But it must very materially lessen their chance of marrying men of any consideration in the world.’ So, there we have it, status and marriage is everything. Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

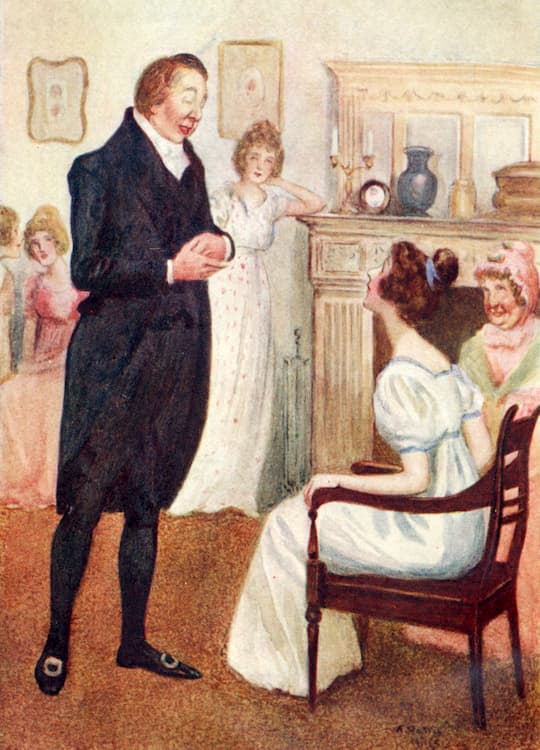

It is unsurprising, therefore, that poor Mrs Bennet’s nerves are again sorely tried when Elizabeth turns down her first proposal of marriage. This proposal comes from none other than Mr Collins, the distant cousin and heir of the Bennet estate, thus such a union would be doubly beneficial to all concerned. Mr Collins announces his intended visit in a letter, the tone of which leads Elizabeth to pronounce him as ‘pompous’ before even meeting him. She is not wrong. The man in person is a very sombre and serious clergyman and the narrator informs us he is ‘altogether a mixture of pride and obsequiousness, self importance and humility.’ (Chapter 15) A little contradictory I hear you cry. His purpose in visiting the Bennets is to find himself a wife, an act which he feels will repair the rift caused by his future inheritance of the estate. He takes every opportunity to namedrop his esteemed benefactor Lady Catherine de Bourgh, who happens to be the Aunt of Mr Darcy. After applying his own form of logical deduction, Mr Collins sets his sights on Elizabeth as the deserving recipient of his proposal. Much to her dismay he orchestrates an interview with her and begins by listing his three reasons for marriage. These are, firstly it is the duty of clergymen to set a matrimonial example; secondly, he proclaims ‘it will add greatly to my happiness’ (Chapter 19); thirdly, Lady Catherine desires him to marry and has twice ‘condescended to give me her opinion (unasked too!) on this subject.’ The final reason appears to be the main driving force.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that poor Mrs Bennet’s nerves are again sorely tried when Elizabeth turns down her first proposal of marriage. This proposal comes from none other than Mr Collins, the distant cousin and heir of the Bennet estate, thus such a union would be doubly beneficial to all concerned. Mr Collins announces his intended visit in a letter, the tone of which leads Elizabeth to pronounce him as ‘pompous’ before even meeting him. She is not wrong. The man in person is a very sombre and serious clergyman and the narrator informs us he is ‘altogether a mixture of pride and obsequiousness, self importance and humility.’ (Chapter 15) A little contradictory I hear you cry. His purpose in visiting the Bennets is to find himself a wife, an act which he feels will repair the rift caused by his future inheritance of the estate. He takes every opportunity to namedrop his esteemed benefactor Lady Catherine de Bourgh, who happens to be the Aunt of Mr Darcy. After applying his own form of logical deduction, Mr Collins sets his sights on Elizabeth as the deserving recipient of his proposal. Much to her dismay he orchestrates an interview with her and begins by listing his three reasons for marriage. These are, firstly it is the duty of clergymen to set a matrimonial example; secondly, he proclaims ‘it will add greatly to my happiness’ (Chapter 19); thirdly, Lady Catherine desires him to marry and has twice ‘condescended to give me her opinion (unasked too!) on this subject.’ The final reason appears to be the main driving force.

Initially he is not at all upset or perturbed by Elizabeth’s refusal because he simply does not believe it. He informs her that he knows she does not mean her words as the fairer sex always refuses at least once in the interests of delicacy. When refuses more forcefully he describes her actions as ‘merely words’ and proceeds again to list his rationale. Once more, his pomposity is evident. He patiently explains his offer is worthy and ‘highly desirable’ due to his ‘connections with the family of de Bourgh.’ He then kindly explains ‘it is by no means certain that another offer of marriage may ever by made you. Your portion is unhappily so small that it will in all likelihood undo the effects of your loveliness.’ The unwillingness of Mr Collins to believe Elizabeth lends the scene something of the farce, not lessened by Mrs Bennet’s abject horror at her daughter’s behaviour. She echoes the sentiments of Mr Collins regarding her daughter’s marriage prospects and advises her ‘if you take it into your head to go on refusing every offer of marriage in this way, you will never get a husband at all – and I am sure I do not know who is to maintain you when your father is dead.’ (Chapter 20) She concludes her speech by declaring ‘Nobody can tell what I suffer! – But it is always so. Those who do not complain are never pitied.’ Once again, Austen provides us with a fine example of a self-obsessed comedic character through her skillful use of dialogue.

Underlying the humour though, lies a darker underside. Although Austen encourages us to find both Mr Collins and Mrs Bennet ridiculous, their dire warnings are grounded in truth and reality. Marriage was serious business and constituted the main driving force behind how women could improve their lives. Mrs Bennet speaks the truth. She would not be able to support her daughters as a widow, and as Mr Collins so charmingly points out, Elizabeth is simply not a good catch. The limited options for her future make her actions all the braver, or foolhardy, depending on your perspective. Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

Despite Charlotte Brontë’s censure of Pride and Prejudice for its ‘neat borders’ and ‘confined houses’ it is such control of subject and style which allowed exploration of the detail of women’s lives and the limited power and choices available to them. So, whether you are more familiar with the BBC adaptation of 1995 featuring an unforgettable Colin Firth as Mr Darcy, or whether, like me you encountered the novel through studying, it is well worth (re)turning to the novel and taking delight in Jane Austen’s richly drawn characters. And as for Mr Collins, please do not worry. He makes a marriage to a more suitable woman, a woman who is the perfect homemaker and who happens to ensure her private lounge is situated as far away as possible from her husband’s study.

Denise Hanrahan-Wells

[1] Quoted in Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Bronte, p.258

Main image: Lyme Park House, Disley, Cheshire, the National Trust property used in the BBC adaptation of P & P. Credit: Andrew Turner / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: The famous first line of Pride and Prejudice. Credit: Sam Oaksey / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above:Portrait of Mr. Collins talking to the Bennet girls. Caption reads: ”I can assure the young ladies that I am prepared to admire them”. First published on 28 January 1813. Illustration by British artist A. Wallis Mills (1878 – 1940). 1908. Credit: Lebrecht Authors / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on the Life and Works of Jane Austen, see The Jane Austen Society UK

Our editions of Pride and Prejudice and more works by Jane Austen can be found here: Wordsworth Editions Jane Austen

Book of the Week: Pride and Prejudice

Books associated with this article

Pride and Prejudice

Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice (Collector’s Edition)

Jane Austen