Book of the Week: Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility was Jane Austen’s first published but second written novel. Denis Hanrahan Wells takes up the story.

She initially began writing it at the age of nineteen under the title ‘Elinor and Marianne’ as an epistolary novel, a form which was very popular at this time. She had begun the novel shortly after completing an early draft of ‘First Impressions’ which was later to become better known as Pride and Prejudice. Both novels were laid aside for some years and Austen was thirty-six by the time Sense and Sensibility was published. She updated her novel to reflect the change in reading tastes by adopting a third person narrator rather than the story being revealed through a series of letters.

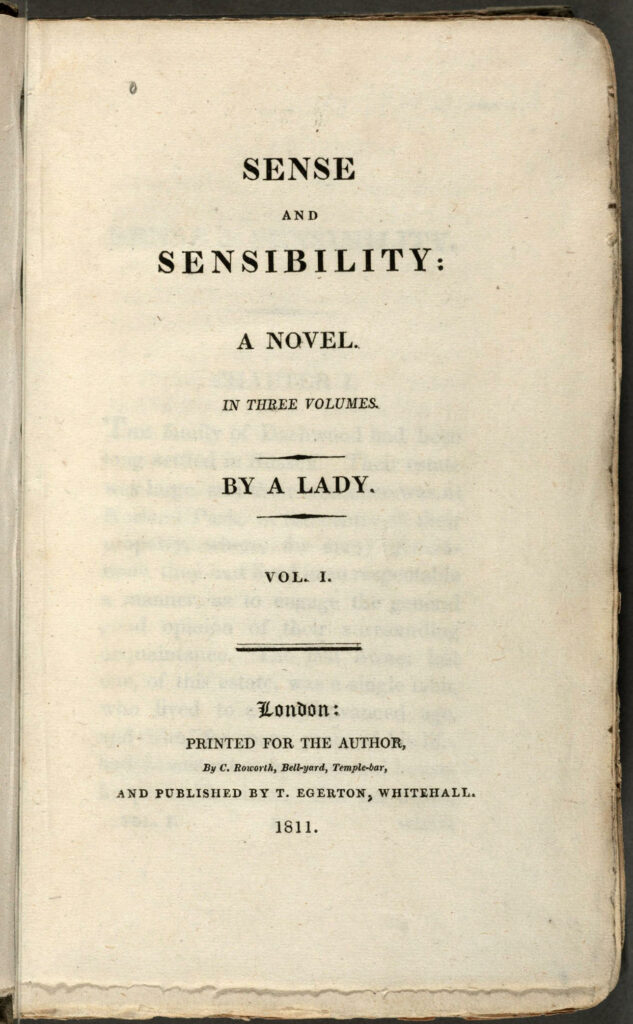

Whilst reworking her novel she put some money aside to cover the costs of self-publishing as she feared she would lose money through her business venture. The novel was published in October 1811 and the title page merely identified the author as ‘a Lady’. She was delighted to receive highly positive reviews and instead of being out of pocket, Austen made a profit of £140 from the first print run. In current terms this is approximately £14,000. According to biographer Valerie Grosvenor Myer[i], if this novel had not been a success Austen would have been unable to afford to publish her subsequent works.

Popular images of Jane Austen are often of a genteel lady writer passing time writing at an elegant but small writing desk. However, when the first edition of Sense and Sensibility had sold out, she was already at work on Mansfield Park, from which she had to break off in order to edit the manuscript of Pride and Prejudice. So, at this point, Austen was effectively a serious writer, earning a reasonable income, despite the necessity to maintain the image that writing was merely a pastime.

Title page of 1811 First Edition

In many ways, Sense and Sensibility is a much less genteel novel than Pride and Prejudice, particularly in how Austen approaches the issues of inheritance and marriage. The problems faced by the Dashwood family of Sense and Sensibility are far more serious than those hanging over the Bennet sisters in Pride and Prejudice. The protagonists of Sense and Sensibility, Elinor and Marianne and their younger sister Margaret are in a very precarious position. Once again, we have an estate which is entailed down the male line of the family, the background of which is established in the first chapter. Mr Dashwood, through no fault of his own, will have to leave the estate of Norland to his son John, from his first marriage. To his second wife and their three daughters he is only able to leave a small income. When he realises his health is failing, he beseeches his son John to ensure his half-sisters and stepmother will be amply provided for. This should not be a problem because John has already received a very healthy inheritance from his mother, the first Mrs Dashwood. John makes such a promise and reassures his father. The only problem is, John is of weak character and his wife has questionable morals. The narrator informs us ‘Mrs John Dashwood was a caricature of himself, more narrow-minded and selfish.’ (Chapter 1) Thus, the selfish Fanny Dashwood easily persuades her husband that they should take up residence in Norland following the death of his father. She also convinces him that his father:

…did not know what he was talking of, I dare say; ten to one but he was light-headed at the time. Had he been in his right senses, he could not have thought of such a thing as begging you to give away half your fortune from your own child. (Chapter 2)

Feeling a moderate amount of guilt for turning his stepmother and sisters out of their home, John decides to ensure they are provided with a good annual income. However, his generosity is a bit too much for Fanny who declares ‘people always live for ever when there is any annuity to be paid them; and she is very stout and healthy, and hardly forty.’ Thus, the calculating Fanny not only ousts the Dashwood ladies from their home but succeeds in reducing their income from £1000 to £500 per annum to the occasional £50. Subsequently, the Dashwood women depart from Sussex and find a modest cottage to rent in the grounds of Mrs Dashwood’s cousin Lord John and Lady Middleton in Barton, Devonshire. Sense and Sensibility

Over the years, much focus has been given to the different characteristics of the two sisters Elinor and Marianne. Elinor is endowed with sense, self-control and ‘coolness and judgement.’ Marianne has the less desirable qualities of sensibility, she is ‘eager in everything; her sorrows, her joys, could have no moderation.’ (Chapter 1) These differences are indeed important in structuring the story of the two sisters as well as providing the title. Without revealing too much, lest you should be unfamiliar with the novel, both sisters fall in love, both sisters face heartbreak, both sisters deal with their troubles in very different ways.

There have been numerous adaptations of the novel, including Ang Lee’s film of 1995 and the BBC three-part series of 2008. Whilst both of these offer more action and a greater sense of drama, the novel provides a darker view of life for women in Georgian England. Jane Austen is renowned for her detailed social observations, but her creation of several unlikeable characters in this novel is particularly biting. Of the aforementioned Lady Middleton the narrator informs us:

‘her first visit was just long enough to detract something from their first admiration, by showing that, though perfectly well-bred, she was reserved, cold, and had nothing to say for herself beyond the most common-place inquiry or remark.’ (Chapter 6)

This is one of the milder criticisms, and is somewhat suggestive of the lack of education available for girls, which may account for Lady Middleton’s limited conversation. Formal education for girls at this time consisted of little more than what finishing schools were later to become and offered very little academic content. Sense and Sensibility

This absence of education becomes evident when the Dashwoods are forced to socialise with the Steele sisters. Of the two, Elinor prefers Lucy finding her ‘amusing as a companion for half an hour’ although any longer becomes trying. This is because, as the narrator informs us, Lucy:

had received no aid from education, she was ignorant and illiterate, and her deficiency of all mental improvement, her want of information in the most common particulars could not be concealed from Miss Dashwood. (Chapter 22)

So much for the genteel lady writer!

Of marriage Austen has much to say and it is unsurprising this is the driving force behind the plots of her novels. Marriage was the only way in which women (and to some extent, sometimes men) could improve their lives, depending on the wealth of the marriage partner. The Dashwood sisters discuss the prospects of the honorable Colonel Brandon who is unmarried at the age of thirty-five, which is somewhat late for men to marry in 1811. A man such as this would be likely to marry a much younger woman and on this Marianne says:

… there would be nothing unsuitable. It would be a compact of convenience, and the world would be satisfied. In my eyes it would be no marriage at all, but that would be nothing. To me it would seem only a commercial exchange, in which each wished to be benefitted at the expense of another. (Chapter 8) Sense and Sensibility

Alan Rickman in the 1995 Ang Lee film

It is significant that such a statement comes from Marianne and not Elinor. As previously mentioned, Elinor is the sister associated with sense. Marianne is associated with sensibility, because she is led by her emotions, which she experiences in the extreme, and even worse, she does not attempt to hide her feelings. To some extent Austen is playing safe by having Marianne speak such controversial words, as she is frequently censured for her lack of control and improper behaviour by Elinor, the sister the reader is presumably meant to exalt. Yet, having any character speak such words was still a bold move.

Of the marriages depicted, most of them are far from happy. Sir John and Lady Middleton are somewhat incompatible. As already mentioned, Lady Middleton is dull whereas her husband is only content when socialising. Similarly, their relatives the Palmers appear to be opposites. Mr Palmer demonstrates his superiority to all and treats everyone with contempt, including his wife. Meanwhile, his wife seems to find everyone extremely amusing, including her husband and frequently laughs at this rudeness. On reflection, maybe they do make a good match.

Again, Austen emphasizes the perception that a woman’s looks are her marketability whilst a man’s income is his and because of this Elinor’s brother becomes concerned about Marianne’s appearance. Marianne has experienced a period of unrequited and unreturned love and John Dashwood notes she ‘has lost her colour, and is grown quite thin.’ He goes on to say ‘I question whether Marianne now will marry a man worth more than five or six hundred a year at the utmost, and I am very much deceived if you do not do better.’ (Chapter 33) A fine example of damning with faint praise.

The critiques of the marriage process continue through the characterisation of the Middleton’s over indulged children. The acidity behind the narrator’s description of the following scene featuring Lady Middleton and her children is unmissable: Sense and Sensibility

‘John is in such spirits today!’ said she on his taking Miss Steele’s pocket handkerchief and throwing it out of the window. ‘He is full of monkey tricks.’

And soon afterwards on the second boy’s violently pinching one of the same lady’s fingers, she fondly observed, ‘How playful William is.’

‘And here is my sweet Annamarie,’ she added, tenderly caressing a little girl of three years old, who had not made a noise for the last two minutes.’ (Chapter 21)

The juxtaposition of the children’s actions alongside their mother’s reactions is a fine example of the many instances of dark humour, which also demonstrates a far from idealized view of marriage and parenthood.

The driving narrative force may be the story of Elinor and Marianne and how their different personality traits lead them to cope in opposing ways with the trials and tribulations of life. Yet Austen once again richly endows her text with sharp criticism of the society in which she was living. The elegantly furnished houses with their well-dressed occupants enjoying a leisured life cannot hide the very real problems women encountered. Inheritance laws favoured men, which in turn ensured marriage was a commodity. The lack of education and opportunity available to women made the marriage market a highly pressurised environment. Thus, the frustrations of a genteel lady writer are not always completely disguised.

[i] See Valerie Grosvenor Myer, Jane Austen: A Biography, 1997

Main image: Kate Winslet, Gemma Jones and Emma Thompson in the 1995 Ang Lee film. Credit: The History Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Title page of the 1811 First Edition, credited to ‘A Lady’. Credit: United Archives GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Alan Rickman in the 1995 film. As Colonel Brandon, he was ‘warm and subtle’. Still looked like the villain, though.

For more information on Jane Austen’s life, visit: The Jane Austen Centre Bath

Our Collector’s Edition Sense and Sensibility can be found here: Sense and Sensibility

Books associated with this article

Sense and Sensibility (Collector’s Edition)

Jane Austen