Book of the Week: The Brothers Karamazov

After an insomniac encounter with a radio adaptation of The Brothers Karamazov, Sally Minogue revisits Fyodor Dostoevsky’s last novel.

I’ve always had trouble sleeping; it’s part of my life. I used to listen to the World Service which gave a non-Anglocentric corrective to the standard news, but eventually the reporting of everyday horrors there became too much. In recent years Radio 4 Extra has come to my rescue, providing some gently mindless drama in the middle of the night to lull me back to sleep. Hercule Poirot is particularly effective. I usually avoid anything of high literary quality because I start listening to it properly. But a couple of weeks ago I was electrified by an adaptation of The Brothers Karamazov into a wakefulness that seemed worthwhile. Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novels are famously big, and this seemed to capture some of his breadth and depth of vision. The dramatisation dated from 2006 and gave the novel a rare five hours of radio time, divided into five meaty hour-long episodes. True, it was rather shouty and the choice of accents a bit strange. But it took me back to my first encounters with the major Russian novels, when I was in my teens and devoured books voraciously. It’s hard to avoid metaphors of food and eating in talking of these works, which you can get your teeth into and which provide nourishment for the mind and the spirit.

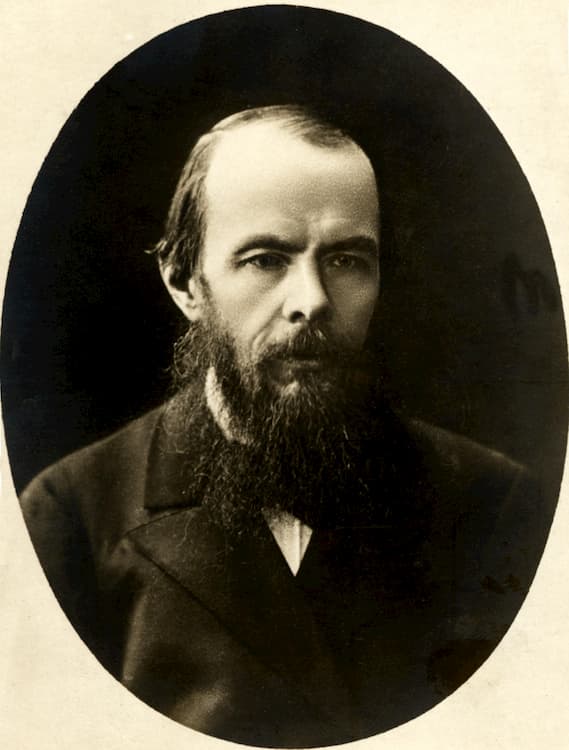

Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Brothers Karamazov was Dostoevsky’s last novel, initially published serially from 1879 to 1880 and in book form in November 1880. The author, whose health had been weakened by lifelong epilepsy, died the following year at the age of 59. He wrote this final novel astonishingly quickly, given its length, complexity and power. While it is thought that he harked back to the draft of an earlier work, the main writing was started only in the summer of 1878, and in common with other novelists of his time, the serial publication began before he had finished writing the later parts of the work. This undoubtedly gives the writing a freshness and intensity, though it must have been unnerving for the author.

What captivated me in The Brothers Karamazov when I was sixteen is what continues to captivate its readers now – the sense of a fully imagined and realised world, inhabited by complex characters and their relationships, but with the whole somehow backlit with a great theatricality, a sense of large, powerful forces interacting at the same time as the smaller human drama is played out before us. This is in part because Dostoevsky deliberately introduces debates, both internal and external, about the great philosophical, ethical and religious questions, not just of his own time but of all time. If this sounds dry, it is not, because we see them enacted in the lives of the main protagonists. I remember thinking – on that first reading innocent of much of what life can throw at us all – ‘If this is the world, let me into it.’ Quite what I made of the violence of that world, I don’t know, but it seemed to be part of an emotional extremity which was probably on the button for a sixteen-year-old. What most struck me was the sweetness of the youngest brother, Alyosha, who abides as a beacon of hope and goodness in the novel, even as he is marked by the dramatic events within it. I had a similar reaction to the ‘hero’ of Dostoevsky’s earlier novel The Idiot (1868-69), Prince Mishkin, who maintains a similar internal beauty and innocence, even as he is depicted as something of a fool.

These characters counterbalance the darker souls who predominate in the novels. In The Brothers Karamazov, Alyosha’s legitimate brothers, Dmitri (Mitya) and Ivan (Vanya), represent diifferent sides of the human condition. Dmitri, closer in nature to his father, is driven by his desires, for his inheritance, for the flighty Grushenka; he uses his betrothed Katerina/Katya, in a relationship founded on the exchange of money for moral assuagement; he puts himself before others, until the very end of the novel. Ivan, meanwhile, struggles constantly and in certain ways admirably with the large questions of religious faith and human suffering, but nonetheless, or perhaps as a result, acts cruelly in many ways. The illegitimate fourth brother, Smerdyakov, who has been despised by everyone, is a sort of alter ego to Ivan, and in key chapters the two talk frankly to each other, Smerdyakov revealing to Ivan that he has acted on his, Ivan’s, ideas in killing their father. Thus Ivan is as guilty as the actual perpetrator, and this fuels a central idea in the novel, that as human beings we are all responsible for each other, and thus we are all in some sense guilty of any individual act.

But such a summary entirely misrepresents the emotional, moral and psychological complications and involvements of the novel. Dostoevsky appears not to judge, and this is a fundamental characteristic of his novels. I say appears, because certain characters are seen as beyond the pale – the brothers’ father Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov has no redeeming features. But that this moral reprobate is the father of such different sons is itself part of the way the novel questions any pat assumptions about human behaviour.

The women Dostoevsky places centrally in the novel are as surprising as their male counterparts. The two key female protagonists, Katerina and Grushenka, take power into their own hands, Katerina by offering herself up to Dmitri to save her father’s reputation, Grushenka by using her appeal to men to keep control of her own life. As is the case with the brothers, both women are changed by their experiences as the novel progresses. One wants to say they are changed for the better, except that we feel Dostoevsky always keeps us guessing as to what ‘better’ is. In the final stages of the novel, they each confront their own feelings, acting in certain ways self-sacrificially, in certain ways selfishly. Sometimes the two coincide. This is the great power of Dostoevsky’s novel. He never shows human motive as simple, rather he shows the interweaving of the many different forces – some of them social and historical, which I have barely touched on – which led human beings to behave as they do. What he reveals most tellingly is the way that those forces are often unknowable to the beings themselves. The Brothers Karamazov

Dostoevsky’s apartment where he wrote ‘The Brothers Karamazov’

Dostoevsky, addressing queries from a reader who did not fully understand some of the movements of his plot, replied ‘Not only the plot of a novel is important for a reader, but also a certain knowledge of the human soul … which each author has a right to expect of his reader’. A large expectation to answer to the largeness of ambition of his novels. It’s intriguing to think of Dostoevsky answering (by letter, of course) individual queries from his audience. This was in part a product of the serialisation system, where readers could comment midstream. Dickens regularly altered the progress of certain novels, or the development of certain characters, in response to popular demand. But the serialization system in Russia was rather different to that in Europe. There it was the practice to have ‘thick’ journals, which allowed Russian novelists more length for instalments. These could be between 30 and 100 pages, with the whole novel out in the journal within a year, so the audience could go on to the next one. That voracious appetite again. Whilst the shorter episodes in English journal publication led to cliffhanger endings, Dostoevsky resisted the serial writer’s tricks. Instead, the Russian ‘thick journal’ system led to each episode having a sense of completion, an identity in itself. ‘Each instalment would, [Dostoevsky] promised Liubimov, his long-suffering editor, have “a finished character, … it would include something whole and finished”’.[1] This also added to the depth and detail of the novel as a whole, as the author sought to make each published serial episode almost a mini-novel in itself.

So what to look out for in what is undeniably a long and demanding read? Well, that itself is, I’d argue, its main pleasure. When we start reading The Brothers Karamazov we enter a world, much of it foreign to us since it is the world of nineteenth-century Russia, but therefore fascinating in its difference. At the same time we encounter movements of the human mind and heart which we will all recognize. But it’s no good thinking we’ll know what to expect – the shifts and turns lead us into unexpected territory, challenge our understanding of ourselves and others, and sometimes confront us with things we don’t want to know about. At times Dostoevsky enters uncharted seas, as with Ivan’s encounter with the devil late on in the novel. On the one hand this is a hallucination brought on by Ivan’s madness. On the other, it gives the novelist the opportunity for Ivan to confront the very force he has himself denied in denying a belief in God; for if God does not exist, neither does the devil. This particular devil is dismayingly ordinary, appearing shabbily dressed, but in once well-made clothes, ‘a poor relation of the best class’, ‘accommodating and ready to assume any amiable expression as occasion might arise’. The devil tempts Ivan as he once tempted Christ. It is of course Alyosha who rescues Ivan.

There is a certain playfulness in Dostoevsky, evident in the above example. Alyosha saves Ivan from the devil by the simple everyday act of knocking on the door, but only to bring the news that Smerdyakov has hanged himself. The ironies of the narrative lend a grim humour to light the darkness of the subject. It was not for nothing that the 20th century Russian literary theorist Bakhtin used Dostoevsky’s novels as a central example for his important ideas about fiction. Bakhtin commended their ‘plurality of independent and unmerged voices and consciousnesses, a genuine polyphony of fully valid voices’. To put it in more straightforward terms, Dostoevsky is giving his characters full rein, their voices cutting against each other (polyphony), their ‘plurality’ allowing the reader to make their mind up – or indeed not.

Dostoevsky’s tomb

My own copy of the novel, an Everyman edition first published in 1927, is translated by Constance Garnett, who brought many Russian novels to an English audience. The introduction is by her husband Edward Garnett, who describes the experience of reading the novel thus:

Immersed in this book one has the sensation of being carried along in a turbulent flood, engulfed in whirlpools of passionate feeling, whirled along in rapids of thought, caught up and held fast in fresh currents of mystical speculation. And the atmospheric pressure increases till the climax is reached.

When we emerge from the maelstrom of this fictional world, we are, I think, changed just by being exposed to it in all its richness and difficulty. But through it all rings the hopeful voice, spirit and presence of Alyosha. He perhaps is a counter-example to Bakhtin’s emphasis on polyphony, since he exemplifies an essentially monolithic view of humanity. Fortunately it is a determinedly optimistic one. In the earliest chapters of the novel we are introduced to Alyosha thus:

There was something about him which made one feel at once (and it was so all his life afterwards) that he did not care to be a judge of others – that he would never take it upon himself to criticize and would never condemn anyone for anything. He seemed, indeed, to accept everything without the least condemnation though often grieving bitterly… The Brothers Karamazov

The novel also ends with Alyosha, exhorting the young schoolboys he has encountered through their cruelty to one of their number (who has now died), and whom he has befriended, encouraged, and changed:

“Ah children, ah, dear friends, don’t be afraid of life! How good life is when one does something good and just!”

This comes after the many horrors that have been recounted in the previous pages. Dostoevsky is similarly unafraid of life, similarly unwilling to judge, and when we step into his world we do, I think, emerge as better human beings.

[1] William Mills Todd III, ‘The Brothers Karamazov and the Poetics of Serial Publication’, Dostoevsky Studies, Vol 7, 1986

The Wordsworth edition (styled as The Karamazov Brothers in line with the introducer’s preference) is here: The Karamazov Brothers

For more information on Dostoevsky’s life and works, visit https://dostoevsky.org/

Main image: Fresco of Dostoevsky in the Moscow Metro station Credit: Sergey Dzyuba / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Dostoevsky’s memorial apartment in Kuznechny Lane in Saint Petersburg, where he wrote the book. Credit: Azoor Photo Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Tomb of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article