Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

On first publication in 1853 Villette received a rather varied reception, and did not achieve the same level of success as Jane Eyre. Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ intext

This was Brontë’s fourth written novel and third to be published. It was also the final novel to be published during her lifetime. Her first written novel The Professor and her final work Villette are connected, in that the latter is a reworking of the former. By 1853 Charlotte Brontë was quite well known within the literary society of London, yet the novel still carried her pseudonym of Currer Bell. Her previous novel Shirley had received some negative reviews, particularly in the Westminster Review but now this journal praised the strength of characterisation in Villette. The Literary Gazette also greeted the novel in favourable terms declaring it ‘retrieves all the ground she lost in Shirley and will engage a wider circle of admirers than Jane Eyre…’ (5 February 1853). George Eliot, writing in the Westminster Review, was much more complimentary describing it as a novel ‘which we, at least, would rather read for the third time than most new novels for the first’ (January 1856). Her friend, sociologist, writer and supporter of women’s suffrage, Harriet Martineau was far less kind in her review for the Daily News. She wrote ‘of her three books, this is the strangest, the most astounding, though not the best…’ She was critical of the characters’ ‘inability to talk about anything other than love,’ and described Brontë’s focus on the search for love as ‘incessant.’ She disliked the anti-Catholic sentiments expressed describing the views presented as ‘a passionate hatred of Romanism.’ She censured Brontë for putting forward such views ‘… at a time when Catholics and Protestants hate each other quite sufficiently’ (February 1853). This review effectively ended the friendship between Harriet Martineau and Charlotte Brontë.

I have found Villette quite challenging to write about, despite having been fascinated by the novel. I found it difficult to know where to start. It is not an easy novel to summarise in terms of plot, neither is it easy to categorise in terms of genre, and I wonder whether this contributed to the mixed reviews on publication. The title refers to the name of a place, rather than referring to the principal character, as in Charlotte Brontë’s previous novels Jane Eyre (1867) and Shirley (1851). Maybe this creates a sense of distance from protagonist Lucy Snowe, despite her first person narration, a narration which is at times unreliable.

It is taken as a given that Charlotte Brontë draws on her experiences of her time spent in Brussels in this novel, but to view the text only in this way would be reductive, as Sally Minogue emphasises in her Introduction to the Wordsworth Classics edition. However, in this blog I have chosen to focus on some of the context surrounding her writing of the novel, as I found this enriched my reading. Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

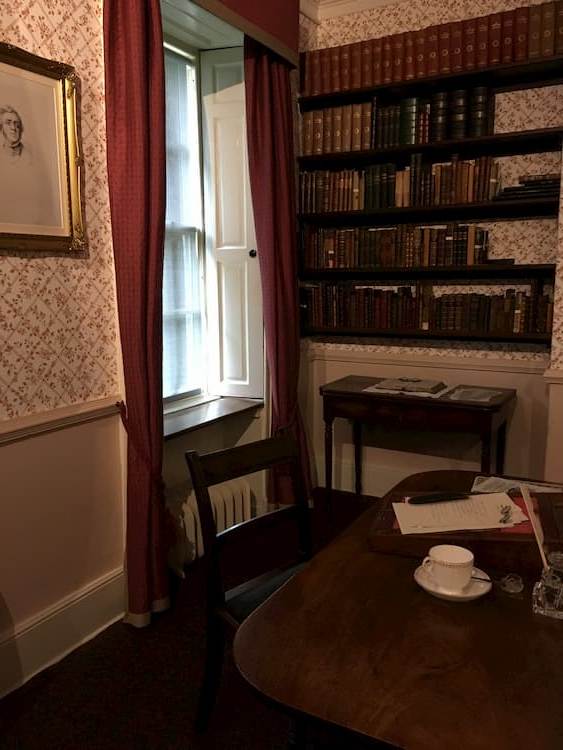

The dining room at Haworth

The narrator, Lucy Snowe, is alone in the world. Incidentally Brontë always intended her to have a ‘cold’ name and right up until the final revisions of the novel she was Lucy Frost. Lucy has no family, is unmarried, and needs to support herself financially in an age where the options for women to live independently were extremely limited. The first six chapters of this three volume novel establish Lucy’s predicament as she reflects ‘self-reliance and exertion were forced upon me by circumstances, as they are upon thousands besides’ (Chapter 4). By Chapter 7 she finds herself in Villette after enduring a harrowing journey, some of which is drawn from Charlotte’s own return journey to Brussels. The perils Lucy endures as a woman travelling alone highlights how difficult it was for women to do so. Lucy is at the mercy of strangers and it is on the suggestion of a young girl (who will recur later in the novel) that she makes her way to the boarding school run by Madame Beck in Villette. She is successful at attaining employment and accommodation, and the majority of the novel follows her life there. In terms of plot, there is little in the way of direct action, simply because it is not that kind of novel. The detail emerges from the emotional and psychological experiences of Lucy, and in many ways, it is easier to identify themes which emerge from the text. These include loneliness, love which is often unrequited and unreturned, repression, female identity, religious conflict and surveillance. You will probably recognize some of these aspects from Harriet Martineau’s criticisms. At times, the novel has quite a gothic feel and there is a mysterious ghostly nun figure. Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

In February 1842 Charlotte and Emily left Yorkshire for the first time and began the long journey from Haworth. Their destination was the Pensionnat Heger, run by Constantin and Zoe Heger, to further their education by studying French and German. After just eight months they received a letter from home informing them their Aunt Elizabeth Branwell was gravely ill, and on the day they were due to begin their journey home, a further letter arrived advising of their Aunt’s death. According to Elizabeth Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë, when the two sisters left Brussels they did not know if they would return again. Constantin Heger wrote a letter of condolence to Patrick Brontë in which he praised the progress Charlotte had made in her studies. Thus, it was decided she would return for a second year of study, in addition to which she would teach English to other pupils. Emily would remain at Haworth. Charlotte departed from home in January 1843, this time making the journey alone, and as previously mentioned, her trials and tribulations are reflected in the journey made by Lucy Snowe. Other experiences make their way into Villette, most significantly in the characterization of the enigmatic teacher Monsieur Paul and the watchful Madame Beck inspired by Constantin and Zoe Heger.

It is apparent a friendship formed between Charlotte and Constantin Heger. Yet some of her letters to friends from October onwards refer to a certain coolness developing in Madame Heger’s attitude towards her. Elizabeth Gaskell[i] suggests the estrangement between the two women was due to religious differences – the Hegers were Catholic, Charlotte was Protestant. Charlotte returned home in January 1844 and had hopes of setting up a school of her own with her sisters. Sadly, this did not come to fruition, although according to the blue plaque, the sisters did teach at the school established by Patrick Brontë in the grounds of the Parsonage. Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

Another failed hope was her desire to maintain contact with Constantin Heger. It seems he was a charismatic character and passionate about literature, and Charlotte hoped to continue their friendship through correspondence. However, the formal tone of his letters and the infrequency of his replies disappointed her, and possibly the open emotion expressed in her letters may have disturbed him. On 24th July 1844 she wrote to him declaring her plans to write a book and to ‘dedicate it to my literature master, to the only master I have ever had, to you monsieur.’ Three months passed and no reply was forthcoming so she sent a further letter, this time a cheerful sounding missive wondering if her previous letters had gone astray. This still received no acknowledgement, leading Charlotte to write a painfilled plea:

…day and night I find neither rest nor peace. If I sleep I have tormenting dreams in which I see you always severe, always saturnine and angry with me. Forgive me then monsieur if I take the step of writing to you again. How can I bear my life unless I make an effort to alleviate its sufferings?

No letters from Constantin Heger have survived, however, four of Charlotte’s letters were kept by Madame Heger, despite Constantin’s attempt to dispose of them. There is evidence some were previously torn up and then later stitched back together. It is thought Madame Heger deemed it prudent to keep them, should any kind of scandal emerge. They were passed down through the family and in 1913 they were donated to the British Library. This was the first time they saw the light of day and proved to be ground breaking material for Brontë scholars. No such material had made its way into Elizabeth Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë.[ii]

The school at Haworth

It was some seven years after Charlotte’s return from Belgium that she began writing Villette. She was now thirty-four years old and had endured much sadness in the preceding three years, having lost Branwell, Emily and Anne. Nevertheless, she had completed Volume One by the end of March 1851. The remainder of the novel made slower progress due to continuing bouts of ill health. A letter to publisher George Smith revealed the difficulties she was experiencing in completing the third volume. She referred to ‘obnoxious headaches, which, whenever I get into the spirit of my work, are apt to seize and prostrate me…’ (3 November 1852). Yet the novel was completed by the end of the month and published in January 1853. Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

The novel’s later publication in Brussels caused a bit of a stir. Some of the experiences described in the novel were drawn from Charlotte’s time there. However, the most controversial aspects were probably the characterization of Monsieur Paul and Madame Beck, inspired by the Hegers. In Villette’s version, the two were not a married couple, Madame Beck, a widow, owns and runs the boarding school and Monsieur Paul Emanuel is the enigmatic professor of literature. Lucy Snowe’s early impressions of Monsieur Paul describe him as austere and irritable, and she goes on to say:

Even to me he seemed a harsh apparition, with his close-shorn, black head, his broad sallow brow, his thin cheek, his wide and quivering nostril, his thorough glance and hurried bearing. (Chapter 14)

This is hardly a favourable description, and Lucy’s interactions with the professor show him to be a tough task master exhibiting what would now probably be described as bullying behaviour. Their relationship undergoes numerous shifts and changes during the course of the novel, which become quite intriguing. If you find the depiction of Monsieur Paul unfavourable, wait until you encounter Madame Beck. Although Madame Beck provides Lucy with somewhere to live, a job and a sense of purpose, this comes at a cost. In Chapter 8 entitled ‘Madame Beck’ Lucy’s description of her first night at the school becomes intertwined with her impressions of Madame Beck. Lucy awakens during the night to discover Madame Beck staring at her face. She feigns sleep and watches as Madame Beck lifts her cap to look at her hair, she then continues her exploration by searching through all of Lucy’s meagre possessions – ‘every article did she inspect.’ She finds a purse and a pocket book which she searches and on encountering keys to Lucy’s trunk, desk and work-box continues her searching. Lucy unconvincingly tries to excuse Madame Beck’s actions as driven by a need to know who was sleeping under her roof but reflects the ’end was not bad, but the means were hardly fair or justifiable.’ Several pages later, Lucy provides further reflection on Madame Beck’s character, little of it favourable and declares ‘Madame Beck ruled by espionage, she of course had her staff of spies’ and that ‘to attempt to touch her heart was the surest way to rouse her antipathy, and to make of her a secret foe.’ Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

Returning to the theme of letters, Lucy later realizes that her letters are also being read by Madame Beck, and she goes to great pains to find a secret hiding place in the grounds of the school. Harriet Martineau’s criticisms of the focus on love and the expression of anti-catholic sentiments is rather an oversimplification. Indeed, these elements are present, but they form part of Brontë’s complex working through of her experiences and emotions as well as a deeper questioning of the difficulties of navigating female identity in the middle of the Nineteenth Century.

Denise Hanrahan Wells

[i] Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, originally published in 1857.

[ii] Further information on the letters can be found at The British Library English and Drama Blog as well as in Claire Harman’s biography Charlotte Brontë: A Life (2015)

Main image: Façades decorated with stone ornaments of medieval guildhalls on the Grand Place / Grote Markt at Brussels. Credit: Arterra Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Pictures 1 & 2 above courtesy of Denise Hanrahan Wells

Information about the Brontë Parsonage Museum can be found here: The Brontë Parsonage Museum

Our selection of editions by Charlotte Brontë can be found here

Charlotte Brontë and ‘Villette’ in Context

Books associated with this article