Dickens’ Other Christmas Books

Goblin Stories and Haunted Men: Stephen Carver looks at Dickens’ Other Christmas Books

As the fairy lights go up and we max out our credit cards, I think we can all agree that Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Consuming it in some form is as much of a tradition as the Bond film. The 1951 film version with Alastair Sim still brings tears to my eyes, while my wife’s favourite is The Muppet Christmas Carol and my son loves Bill Murray’s Scrooged. (We will watch them all this month.) And then there’s The Man Who Invented Christmas, a film about Dickens writing A Christmas Carol, and a new adaptation on the BBC this Christmas, from the team that bought us Peaky Blinders. You can’t get away from it, and rightly so. Dickens’ redemptive gothic novella still carries enormous power – a loud and enjoyable hymn to human decency, love and civic responsibility that makes us all want to be a better person, at least for one day. On reading it in 1874, for example, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote to Mrs Sitwell that, ‘I feel so good … and would do anything, yes and shall do anything, to make it a little better for people. I wish I could lose no time; I want to go out and comfort someone!’ (Colvin: 1912, 88).

What’s perhaps less well-known is that A Christmas Carol was the first in a series of Christmas books by the great man – an ongoing project that combined the core themes of charity and redemption with a critique of the Utilitarian indifference to the hopeless lot of the poor. These follow-up stories are not as iconic as A Christmas Carol, and the Muppets have never done one. Nonetheless, they remain well worth a read, especially at this time of year.

Dickens loved Christmas, a celebration that was acquiring its current form in the late eighteen and early nineteenth centuries. Influenced by Washington Irving, who included four essays on Christmas traditions in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent, Dickens believed that an old English Christmas could foster the kind of social harmony that he felt had been lost in the brutal Darwinism of the Industrial Revolution. When Scrooge talks of the poor dying to ‘reduce the surplice population’, for example, he is quoting Thomas Malthus’ An Essay on the Principle of Population, which rejected charity and influenced both Whig and Tory economic policy in the 1830s. Before A Christmas Carol, which was thrown together to offset the commercial failure of Martin Chuzzlewit in 1843, Dickens had already written about ‘Christmas Festivities’ for Bell’s Weekly Messenger in 1835, which became ‘A Christmas Dinner’ in Sketches by Boz, and, most notably, added ‘The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton’ to The Pickwick Papers, in which the solitary and mean-spirited Gabriel Grub discovers the true meaning of Christmas after being shown the past and future by graveyard goblins.

After the success of A Christmas Carol, albeit muted by a reckless decision on the author’s part to shoulder the expenses for the book’s colourful seasonal design, and warmed by overwhelmingly positive reviews, Dickens resolved to embark upon a series, later writing that, ‘My purpose was, in a whimsical kind of masque which the good-humour of the season justified, to awaken some loving and forbearing thoughts, never out of season in a Christian land’ (Dickens: 1920, 1). In 1844, one year on from A Christmas Carol, Dickens wrote The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that Rang an Old Year Out and a New Year In which was, like its predecessor, published by Chapman and Hall. It was illustrated by Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, William Clarkson Stanfield and John Leech, the latter having also illustrated A Christmas Carol. The Chimes is an often very angry piece, even more, critical of prevailing social and economic theory than A Christmas Carol. As his best friend and later biographer, John Forster wrote:

When he came therefore to think of his new story for Christmas time, he resolved to make it a plea for the poor. He did not want it to resemble his Carol, but the same kind of moral was in his mind. He was to try and convert Society, as he had converted Scrooge, by showing that its happiness rested on the same foundations as those of the individual, which are mercy and charity, not less than justice (Forster: 1905, I, 386).

As The Chimes long subtitle suggests, like A Christmas Carol, the premise goes back to the light-hearted Pickwick story. Toby ‘Trotty’ Veck is an elderly ‘ticket-porter’ – a casual messenger – living in squalor by an ‘old church’ (depicted as St Dunstan-in-the-West by Stanfield). He feels an affinity with the church bells and makes up jolly little rhymes in time with their chimes, while rejecting the local rumour that they are haunted. He is, however, beginning to lose faith in human nature. He is frightened by newspaper reports of crime and immorality, and increasingly wonders if the working classes are simply ‘wrong every way’ and ‘born bad’.

His daughter Meg and her fiancé, Richard, intend to marry on New Year’s Day, but when they come to tell Trotty, they are buttonholed on the street by three gentlemen. The pompous Alderman Cute prides himself on his ability to converse with the lower orders and sometimes hires Trotty. He is accompanied by a political economist called Filer, and a ‘red-faced gentleman’ who Dickens implies is a member of the ‘Young England’ group, a public-school political faction with nostalgia for feudalism. This posh trio wear the young lovers down until each believes, as Filer explains as ‘a mathematical certainty’, that ‘they have no right or business to be married’ and, indeed, ‘no earthly right or business to be born’. The friendly refrain of the bells in Trotty’s head is overwritten by their slogans: ‘Put ’em down, Good old Times, Facts and Figures!’ (Dickens: 1920, 72–74).

Cute sends Trotty to deliver a note to Sir Joseph Bowley MP, who fancies himself ‘the Poor Man’s Friend and Father’ but exhibits a crass indifference to the plight of the working class. This was a satirical portrait of the Whig ex-Chancellor Lord Brougham, just as Cute is the notorious Middlesex magistrate Sir Peter Laurie and Filer represents Malthusian theorists in general, as did Scrooge. Trotty meets a poor man called Will Fern and his orphaned niece Lilian on the long walk home. Fern has been accused of vagrancy and intends to visit Cute to clear his name. From something he overheard at Bowley’s, Trotty knows Cute intends to ‘Put Down’ (imprison) Fern and he warns him to stay away, taking the pair home and feeding them. Meg is there, and the marriage appears to be off.

That night, the bells call out to Trotty. He climbs the tower where the spirits of the bells and their goblin keepers rebuke him for losing faith in himself and his class and thus humanity’s potential for change and growth, which seems a bit harsh. They tell him he is dead and forces him to watch the tragic lives of Meg, Richard, Will and Lilian unfold without being able to intervene, much like the wandering spirits of A Christmas Carol. What follows is incredibly bleak, and it is Dickens’ raw portrayal of poverty and hopeless toil that lingers in the mind after reading, rather than the upbeat denouement. The aristocratic villains remain unmoved and unpunished at the conclusion of the narrative.

Widely anticipated after A Christmas Carol, The Chimes was a hit, although whereas the critical opinion of the former had been overwhelmingly positive, it was more divided now. Some reviewers were sympathetic to its social message, some said it read like a police report, and others thought it dangerously radical. The Northern Star dubbed Dickens the ‘champion of the poor’.

The following year Dickens moved away from the politics of A Christmas Carol and The Chimes in favour of their more fantastic elements. The Cricket on the Hearth, subtitled ‘A Fairy Tale of Home’ (1845), started out as an idea for a periodical with a domestic focus to be called The Cricket. Forster talked him out of this, and as a writer wastes nothing the premise became the next Christmas book, this time published by Bradbury and Evans and again illustrated by Maclise, Leech, Doyle, and Stanfield, with additional drawings by Edwin Henry Landseer.

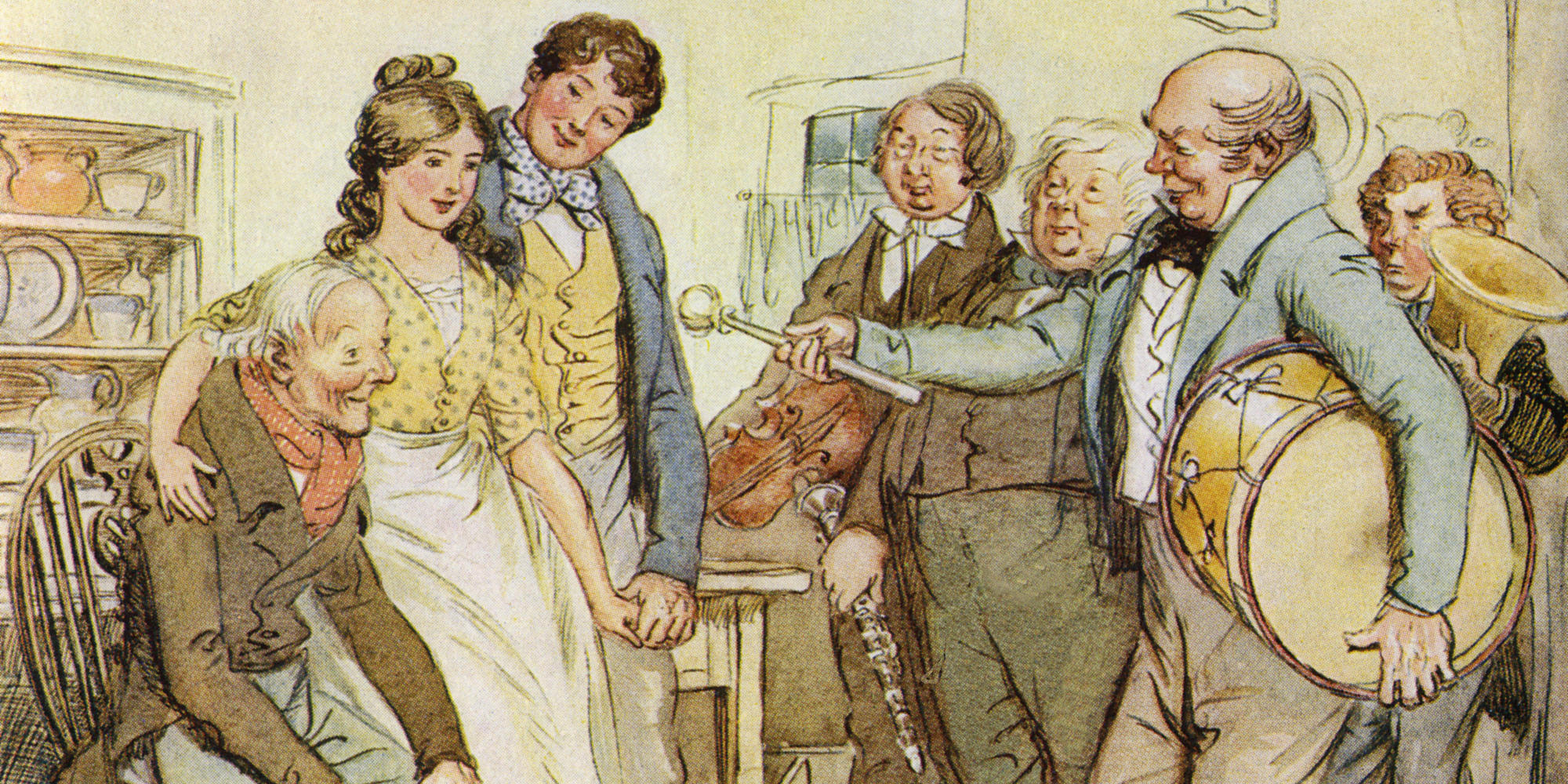

The Cricket on the Hearth is a domestic melodrama with a focus on individual transformation rather than social change. Again, the central characters are working class, and in one case blind, although they are depicted as fundamentally content, hard-working country folk, and thus a long way from the grinding urban poverty of the first two Christmas books. The overall tone is gently humorous, with a lot of romantic misunderstandings and misdirection in the manner of a Shakespearian comedy. (Fans of Dickens will also note a plot device that will later turn up in David Copperfield.) There is also a Scrooge figure, the miserly toy manufacturer Tackleton, who despises children and directs his toymakers to make his wares frightening in a nice running gag until his inevitable revelation in the third act. The cricket on the hearth is a kind of guardian angel to the Peerybingle family, the heroes of the tale, and when discord comes, it appears ‘in Fairy shape’ to John Peerybingle and marshals the ‘Spirits of the house’ to give him a vision that saves his marriage. The story is predominantly about love – between men and women, parents and children, friends, and the sacrifices made in its name – and Dickens portrays these inner processes movingly and honestly. Everything works out in the end, and the book ends with everyone dancing. As a feel-good story, The Cricket on the Hearth was an enormous success, Thackeray writing of it, ‘To us, it appears it is a good Christmas book, illuminated with extra gas, crammed with extra bonbons, French plums and sweetness’, although a Times review lamented its sentimentality (RSL: 1963, 103).

Retaining a similarly rural setting to The Cricket on the Hearth, Dickens’ next Christmas book was The Battle of Life: A Love Story (1846), again published by Bradbury and Evans and illustrated by Charles Green. The story was conceived while visiting Switzerland. Inspired by the sublime grandeur of the Alps and the country’s historic monuments, Dickens resolved to write an allegorical tale of nobility and heroism in a domestic setting. He did this through the controlling metaphor of an epic medieval battle. The reasons for the conflict are long forgotten, the battlefield has become an orchard and the book opens with a powerful and evocative description of the battle and time passing. The land is owned by the jovial cynic Dr Jeddler, whose ‘philosophy’ was ‘to look upon the world as a gigantic practical joke; as something too absurd to be considered seriously by any rational man’ (Dickens: 1920, 184). As another character who has lost faith in the human spirit, Jeddler’s redemption comes not through any supernatural agency but by the noble actions of his two daughters, who both hide their love for his ward, Alfred, so that the other might marry him. In common with The Cricket on the Hearth, the plot relies on melodrama and misdirection and the ending is a happy one. The underlying moral of the story is expressed by the mottos on two tokens belonging to the semi-literate servant Clemency Newcome (a forerunner of Peggotty in David Copperfield): ‘Do as you would be done by’ and ‘Forget and Forgive!’ The story is not set at Christmas, and there are no fantastic elements.

Although he was initially enthusiastic about the project, Dickens was writing it in tandem with the monthly instalments of Dombey and Son and his letters show that the process was a struggle. He also found the novella format restrictive – each book is about 100 pages – and the realistic mode did not allow for ghosts and visions to move the narrative along quickly, leading to a pretty inelegant plot device to resolve the central mystery. He later wrote to friend and brother-author Edward Bulwer-Lytton that, ‘I was thoroughly wretched at having to use the idea for so short a story. I did not see its full capacity until it was too late to think of another subject; and I have always felt that I might have done a great deal with it, if I had taken it for the groundwork of a more extended book’ (Qtd. in Forster: 1905, I, 503). He also realised too late that the absence of seasonal fantasy was a terrible mistake commercially. The Battle of Life never attained the popularity of the previous Christmas books and seems oddly out of place in the series. Lytton suggested that he might rewrite it, and Dickens later used the premise of sacrificing oneself for love in Sydney Carton’s narrative in A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

As he was still working on the Dombey and Son serial the following year, Dickens decided not to write a Christmas book. This was despite already having conceived ‘a very ghostly and wild idea’ and being ‘loathe to lose the money’ and ‘still more so to leave any gap at Christmas firesides which I ought to fill’ (Forster: 1905, I, 485). The ‘wild idea’ was put on hold until the summer of 1848.

The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain: A Fancy for Christmas Time was published by Bradbury and Evans on December 19, 1848. Leech and Stanfield returned as illustrators, joined by Frank Stone and John Tenniel. This was to be the last of Dickens’ Christmas books, and in many ways it returned to its source, having much in common with A Christmas Carol. As its title suggests, The Haunted Man is a gothic fantasy divided, like the Carol, into five sections. It is a doppelgänger story like Poe’s ‘William Wilson’, and the protagonist, the research chemist Redlaw, his ‘haunted’ by an aspect of himself, just as Marley’s ghost is a double of Scrooge. There’s also a cheery but chaotic working-class family – the Tetterbys – and the neglected children ‘Ignorance and Want’ are manifest as the ‘waif’, a feral boy taken in by Redlaw’s servant, the childless and angelic Milly Swidger. The story is also set at Christmas.

Redlaw is another solitary and embittered protagonist. His withdrawal from humanity is the result of his failure to move on from past injustices and the death of his sister. His shadowy double appears to be these negative automatic thoughts externalised, while also sharing traits with more conventional apparitions ¬– the temperature drops when it appears, and organic matter decays:

As the gloom and shadow thickened behind him, in that place where it had been gathering so darkly, it took, by slow degrees,—or out of it there came, by some unreal, unsubstantial process—not to be traced by any human sense,—an awful likeness of himself!

Ghastly and cold, colourless in its leaden face and hands, but with his features, and his bright eyes, and his grizzled hair, and dressed in the gloomy shadow of his dress, it came into his terrible appearance of existence, motionless, without a sound. As he leaned his arm upon the elbow of his chair, ruminating before the fire, it leaned upon the chair-back, close above him, with its appalling copy of his face looking where his face looked, and bearing the expression his face bore. (Dickens: 1920, 252).

Like a depressive and his therapist, the two discuss Redlaw’s grief and resentment, and eventually, the ‘phantom’ offers him a way out, a ‘gift’ to ‘Forget the sorrow, wrong, and trouble you have known’. Redlaw accepts, and the bad memories are magically removed. But just as Dr Jekyll will later attempt to separate ‘all that was unbearable’ from his mind, leaving only his ‘moral side’, it all goes horribly wrong (Stevenson: 1979, 82). Without his pain, Redlaw also ceases to feel anything except a brutal, gnawing cynicism, incapable of sympathy or kindness; worse, his presence seems to transmit this to others. Only the homeless waif is immune, having no good memories to lose. Now Redlaw must undo the damage he has done to his neighbours, retrieve his memories and embrace spiritual growth. Like Ebenezer Scrooge, he must learn that his ‘intertwisted chain of feelings and associations’ is ‘in its turn dependant on, and nourished by, the banished recollections’ – that we cannot have pleasure without pain, and that the memory of this pain is the source of empathy and compassion, a lesson he learns from Milly.

The Haunted Man was moderately successful in its own day, helped by some strong stage adaptations and revived in the 1860s with the addition of ‘Pepper’s Ghost’, a special effect using glass and trap doors that produced an apparition the actors could apparently interact with. It has not, however, endured as either a Christmas or a ghost story in the popular consciousness; in fact, none of these stories has, with the obvious exception of A Christmas Carol. These are the Christmas stories by Dickens that most people have never heard of.

And so ended Dickens’ run of Christmas books; not because they had ceased to be popular in their own day, but because of his foundation of the periodical Household Words, in which he continued to communicate his idealised Yuletide message of compassion, generosity and hope through the magazine’s annual ‘Christmas Numbers’.

Throughout his career, Dickens used his art to fight social injustice, but it is in the Christmas books that his message is at its purest, hence the continuing popularity of his masterpiece, A Christmas Carol. It speaks to us in a very direct way. By adopting the form of the modern fairy tale, the fantasy paradoxically heightens the reality, while simplifying the moral lesson. These aren’t children’s books, but they teach us like children, remind us of our own childhoods, and that humanity’s worst crime is allowing children to suffer. Dickens used each of his Christmas stories to explore and refine this message, and to come at it from some very different angles. So, don’t just stop at A Christmas Carol; read the other books and have a very Merry Christmas.

WORKS CITED

Colvin, Sidney (ed). (1912). Letters And Miscellanies Of Robert Louis Stevenson. New York: Charles Scribner.

Dickens, Charles. (1920). A Christmas Carol and Other Stories. London: Odhams Press.

Forster, John. (1905). The Life of Charles Dickens. 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Royal Society of Literature. (1963). Essays by divers hands: being the transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom. Vol 32. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. (1979). The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. London: Penguin.

Image: Alamy.com The Chimes by Charles Dickens. Illustrations by Hugh Thomson. First published in 1844. The caption reads: ‘ The drum- then stepped forward’. Shows Meg and Richard’s wedding feast after Trotty’s awakening.

Books associated with this article

Christmas Books

Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens