Sally Minogue takes us back to Dracula, the novel.

As a new adaptation of Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’ hits both BBC One and Netflix, Sally Minogue takes us back to the original novel.

The New Year will be ushered in, some might think appropriately, with a horror story, as television audiences are offered a reworking of Bram Stoker’s classic novel, Dracula. In an innovative collaboration, it will be shown first in three consecutive episodes on BBC One (January 1st, 2nd and 3rd), and then immediately released on Netflix on January 4th [Trailer now available on BBC iplayer and further information on Wikipedia]. This adaptation comes from the creative imaginations of Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, late of Dr Who and the brilliant and captivating Sherlock, so viewers will know they are in for a treat. Judging by the teaser trailer now available, it will be scary, eroticized treat, delving back into film history with references to Bela Lugosi and Nosferatu, and forward into a twenty-first-century queering of a nineteenth-century tale of male vampirism feeding on female passivity. Judging by the cast list, Stoker’s central classic victim-heroine, Lucy Westenra, is dispensed with altogether, which seems to be throwing the baby out with the bathwater. But we await events, a differently gendered victim, and a different reading of Dracula.

Meanwhile, let’s to the novel itself, and a rich, varied, fascinating novel it is. For readers, its greatest qualities are those which can’t possibly transmit to the screen. For this is a novel of multiple narratives and viewpoints. There is no external narrator, and as Stoker puts it in a prefatory epigraph: ‘all the records chosen are exactly contemporary, given from the standpoints and within the range of knowledge of those who made them.’ This was particularly important, with some sense of objectivity achieved by different subjective narratives laid side by side, giving different accounts of the same events, when the author was dealing with matters which challenged belief. Stoker was trying to give some sense of historical veracity to underpin a story quite lacking in that. You can see him reaching back to narratives such as Wuthering Heights, with its framework narrations, and drawing on the authenticity of the first-person document – the newspaper article, ship’s log, journal, diary, phonograph entry, letter, even telegram. This gives the reader a unique engagement, as we are left to interpret these ‘documents’ against each other, some of them apparently factual, some of them personal. Meanwhile, the authors of these documents, the characters in the novel, are themselves trying to come to terms with events and experiences that challenge their own understanding of the world. Stoker’s interest in new technology carries this fin-de-siècle novel forward into the new century even as it reaches far back into the stuff of nightmare.

At the centre of this is a great big myth, one might say an untruth, but one which clearly exercised and entertained imaginations in the nineteenth century – that of the vampire. Stoker gives us various views of this dreaded figure. From the point of view of Jonathan Harker (a solicitor unlucky enough to have Count Dracula as his client), we meet the standard Gothicised vampire in, or in fact out of, his own Transylvanian castle:

But my very feelings changed to repulsion and terror when I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over that dreadful abyss, face down, with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings.

And then, again from Harker’s viewpoint, we meet him in his Hammer horror incarnation, no doubt derived in the first place from Stoker’s classic text:

… so I raised the lid and laid it back against the wall; and then I saw something which filled my very soul with horror. There lay the Count, but looking as if his youth had been half-renewed … the cheeks were fuller, and the white skin seemed ruby-red underneath; the mouth was redder than ever, for on the lips were gouts of fresh blood, which trickled from the corners of his mouth and ran over the chin and neck. Even the deep, burning eyes seemed set amongst swollen flesh, for the lids and pouches underneath were bloated. It seemed as if the whole awful creature were simply gorged with blood; he lay like a filthy leech, exhausted with his repletion.

The solicitor gives us chapter and verse, but he also gives us a delight in horror through the language, gorged with sensuous detail as Count Dracula is gorged with blood.

But it is when the vampire Count comes to the ordinary shores of Yorkshire, aboard a ship helmed by a corpse, that terror enters the lives of ordinary souls. The account of Demeter’s entry into the harbour in the eye of the storm, given through the eye-witness account of ‘The Dailygraph’, is one of the consummate Gothic/realist descriptions, echoing J.M.W. Turner’s painterly representations. Over several pages, Stoker allows himself to move from the natural to the possibly supernatural, never letting go of the underpinning reality of the dreadful storm. It is within this framework, in dead of night in the light of a full moon, and in the shadow of the ruined Whitby Abbey, that Lucy falls victim to Dracula. Her fate is here glimpsed but not fully understood by her friend Mina, fiancée and eventually wife to Jonathan, the previous observer:

There was undoubtedly something, long and black, bending over the half-reclining white figure. I called in fright, “Lucy! Lucy!” and something raised a head, and from where I was I could see a white face and red, gleaming eyes. … When I bent over her I could see that she was still asleep. Her lips were parted, and she was breathing – not softly, as usual with her, but in long, heavy gasps, as though striving to get her lungs full at every breath.

Of course, it’s all over with Lucy; infected by Dracula’s fatal kiss, and by her own answering desires, she has to die. Even had she survived with the interventions (fascinating, these) of Dr Van Helsing, and his direct, person-to-person blood transfusions, she couldn’t have remained the translucent Lucy, golden and innocent. Her friend Mina is a tougher figure and she survives. If it is implied she is less attractive to the blood-sucking Dracula because less of the standard nineteenth-century passive heroine – all well and good.

Mina presages the New Woman of the turn of the century, just as Dracula presents us, in 1897, with a novel for a new age, and indeed a novel for the current age. This text can turn any and which way. Masses of obvious stuff about sexuality, but while female vampires lick their lips like animals, the more disturbing scenes are those in which bodily fluids are interchanged in an ordinary room, vein to vein, in the name of science. This fantasy of male lifeblood reinvigorating the female (‘A brave man’s blood is the best thing on this earth when a woman is in trouble’) also normalizes and scientises the sexual, with a drugged Lucy passively imbibing her fiance’s blood, and by the turn that of several other men. But this is also a disturbing text in a larger way. Whether via the solicitor Harker’s venture into Transylvania, or as Dracula himself scales the wall of an ordinary residence in Whitby and sinks his deadly teeth into Lucy’s innocent neck, Stoker shows us horror entering into the bourgeois life, where it is most frightening. There’s something interesting here about the adaptation being shown on Netflix: the eruption of terror into the everyday life of the laptop and the smartphone mirrors Stoker’s original conception.

This most imaginative of novels looks ahead to the existential terrors that would be explored by modernist writers such as Virginia Woolf. Stoker’s blood-soaked text is worlds away from Woolf’s cool interrogations into consciousness. But mark my words: they’re looking into the same abyss. Let’s see whether Gaitiss plumbs some of those depths in his adaptation, or only skims the surface.

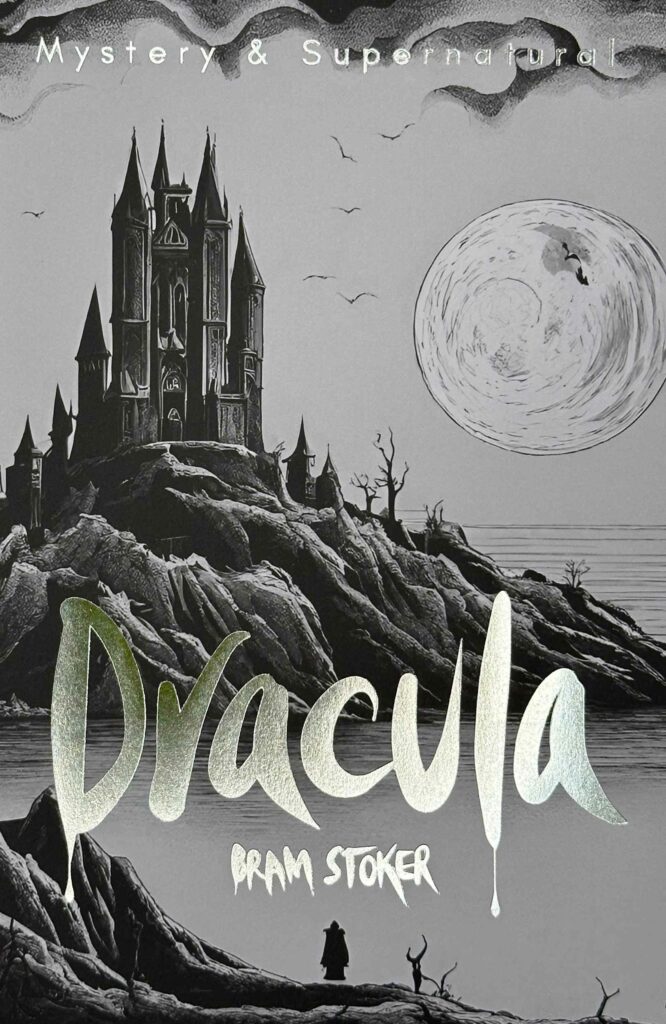

Image: Bran Castle Museum, near Brasov, Transylvania, Romania, known as the Castle of Dracula. Contributor: Mark Wiener / Alamy Stock Photo