Book of the Week: Bleak House

Keep out of Chancery… it’s like being ground to bits in a slow mill; it’s like being roasted at a slow fire; it’s being stung to death by single bees; it’s being drowned by drops; it’s going mad by grains.’ John Jarndyce, Bleak House

Bleak House (1851-53) is one of Dickens’ greatest novels. It has an integrated plot which develops naturally, encompassing and involving the vast array of characters in a unified tale that Dickens brings forth from his fertile imagination. Unlike some of his other works, this novel contains no episodes that do not have a direct relevance to the main plot. Professor J. Hillis Miller, author of Charles Dickens, The World of his Novels, observed that in writing Bleak House: ‘Dickens constructed a model in little of English society in his time. In no other of his novels is the canvas broader, the sweep more inclusive, the linguistic and dramatic texture richer, the gallery of comic grotesques more extraordinary.’

The story revolves around an infamous court case, Jarndyce versus Jarndyce, which has been rolling on for years in the court of Chancery with little hope of it ever being resolved. All the characters in the novel are in some ways touched by this impenetrable lawsuit. It is Dickens’ merciless indictment of the Court of Chancery and its bungling and morally corrupt handling of the Jarndyce case that gives the novel scope and meaning. It ruins and taints all who come into contact with it.

Esther Summerson, who narrates much of the story, gives an account of her unhappy childhood and becoming a protégée of the honest and worthy John Jarndyce, who is guardian to Ada Clare and Richard Carstone. Richard and Ada wish to marry but his vacillations in choice of career and his inability to stick with his choices lead him to put all his faith in the resolution of the Jarndyce case in which he has a financial interest. This inevitably leads to tragedy.

The story is developed by the introduction of the pompous Sir Leicester Deadlock and his proud wife, Lady Deadlock. She harbours a dark secret, which is slowly unravelled by the coldly calculating heartless lawyer Tulkinghorn – one of Dickens’ greatest creations.

Numerous other characters contribute to the complex portrait of society which emerges from the novel. They include Harold Skimpole who pretends he is ‘but a child’ and has no talents whatsoever as he leeches on others; Krook, the rag and bottle shopkeeper who dies a hideous death from ‘spontaneous combustion’; Mrs Jellaby, neglectful of her own family while spending her energies on ‘Telescopic Philanthropy’, caring for natives in Africa; and one of my favourite players in the drama, Guppy, the young clerk, the unrequited lover of Esther Summerson – he is both a sad and comic character, but brilliantly portrayed. Of particular importance to the moral design and message of the novel is Jo the crossing sweeper whose brutish life and death are the instrument for one of Dickens’ most savage judgements on an indifferent society.

The novel has an interesting narrative structure which, it has to be said, has not pleased all the critics. The story is told by a third-person narrator who is both dispassionate and objective; and also by a first-person narrator, Esther Summerson, who describes the circumstances of her life and those of her acquaintances with a sensitive and emotional voice, as is natural for a character at the heart of the maelstrom of drama in the novel – rather like David in David Copperfield and Pip in Great Expectations. As result of this approach to storytelling, the contrast in narrative styles in Bleak House gives the reader a much more detailed and comprehensive view of events.

George Gissing and G.K. Chesterton are among those literary critics and authors who considered Bleak House to be the best novel Charles Dickens ever wrote. And I cannot disagree with them. As Chesterton put it: ‘Bleak House is not certainly Dickens’ best book; but perhaps it is his best novel’. Daniel Burt, in his book The Novel 100: A Ranking of the Greatest Novels of All Time ranks Bleak House at number 12, while Stephen King named it among his top ten favourite books.

In the late nineteenth century there were three minor stage plays based on the novel. However, an evening in the theatre can in no way encompass the vast and intricate scope of the novel or its vast cast of characters and so these dramas cut out much of the text and concentrated on the role of the street sweeper Jo.

Bleak House BBC 2005

There were two silent movies in the 1920s, one of which starred Sybil Thorndyke as Lady Deadlock, but since then movie makers have steered clear of the novel, realising that to capture its brilliance would require hours and hours of screen time. That is where BBC Television comes in. They have produced three serials over the years. The first was in 1959: an eleven part series of thirty minute episodes with Andrew Cruikshank as John Jarndyce and John Phillips as Mr Tulkinghorn. The performances of the cast were praised by the press, but the narrative was squeezed somewhat and a number of interesting characters such as Mrs Jellaby and Mr Skimpole were lost. The second television adaptation in 1985 starred Diana Rigg as Lady Deadlock , Robin Bailey as Sir Leicester and Peter Vaughan as Tulkinghorn. This was a fine series but it has since been eclipsed by a version produced in 2005 with a stunning script by Andrew Davies, encompassing all the themes and tropes of the original book along with a stellar cast, all of whom were on top form. The cast list is too long to hand out bouquets to them all, but special note must be made of the stunning performances of Charles Dance as Tulkinghorn, Gillian Anderson as Lady Deadlock and Anna Maxwell Martin as Esther Summerson. This series remains one of the jewels in the BBC’s crown.

Bleak House is a dark, rich confection, high in drama, deep in meaning, running the gamut of tragedy and farce. It is steeped in its time and yet speaks clearly to the modern reader. Dickens knew that costumes and manners were incidental to the workings, emotions, trials and tribulations of mankind. In this novel, all human life is there. I commend it to your attention.

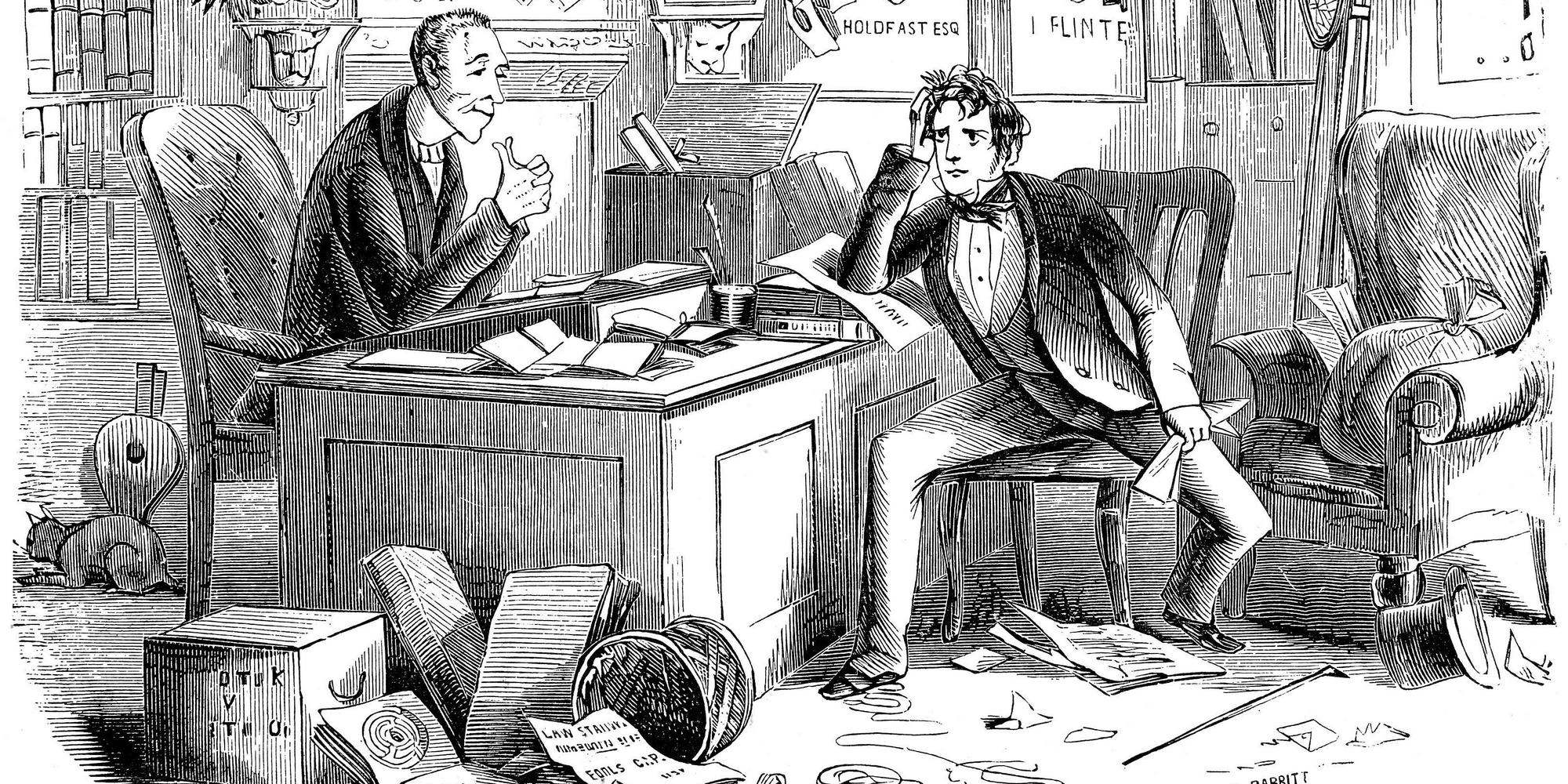

Main image: ‘Attorney and client: fortitude and patience.’ Wood engraving after a 19th-century American edition of ‘Bleak House.

Credit: GRANGER – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image above: BBC production of Bleak House 2005, photo: © BBC / Courtesy: Everett Collection

Credit: Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article