‘Conclusions most forbidden’: Frankenstein and the Romantic Hero

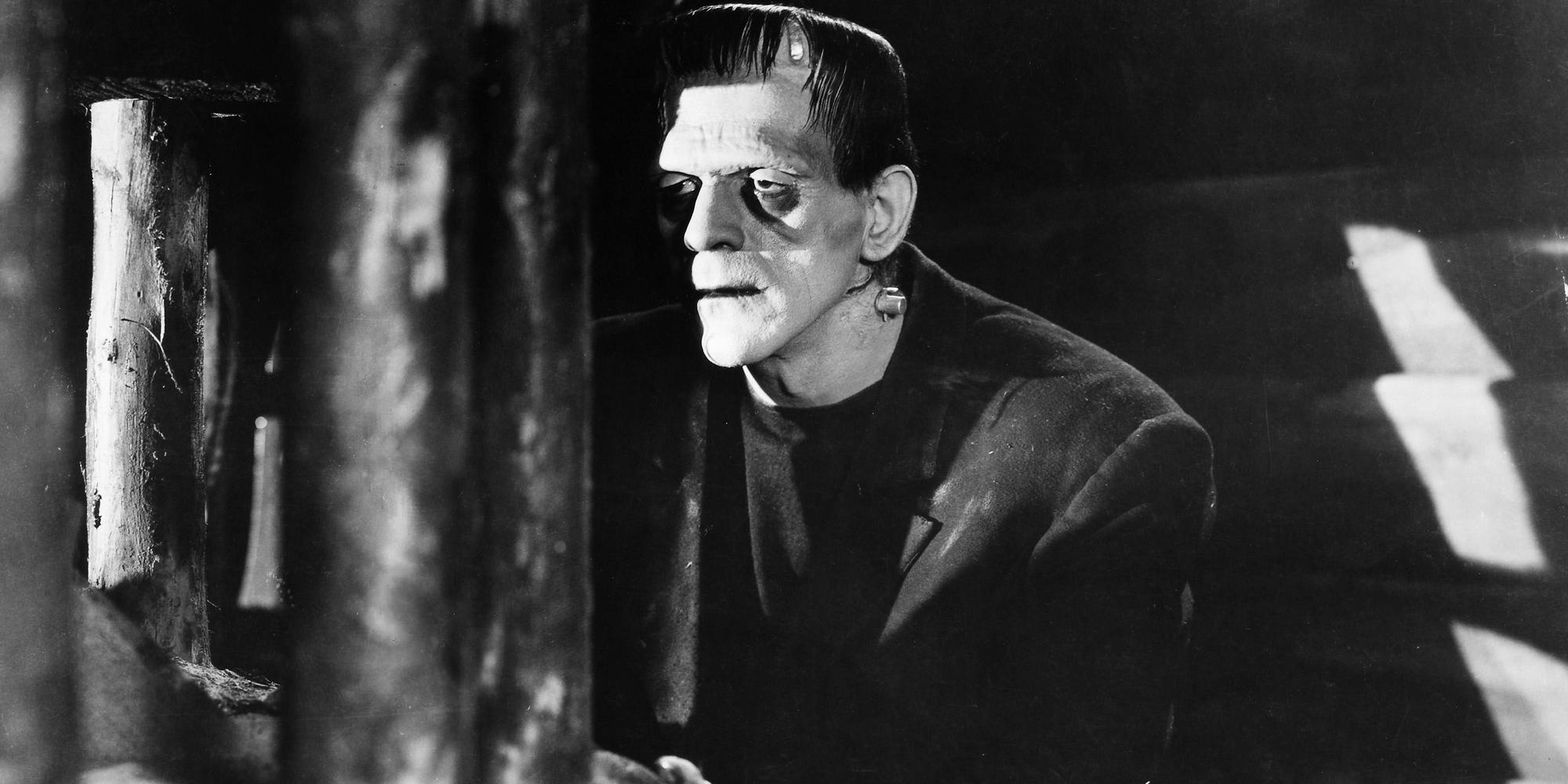

To read Frankenstein is to enter a realm of intersecting myths. It is there immediately in the novel’s original subtitle ‘The Modern Prometheus’, a comparison between the Faustian Victor Frankenstein and the Titan who stole fire from the gods and was punished horribly for gifting it to humanity. As a response to Milton’s Paradise Lost the novel explores and interrogates the Christian myths of creation and fall. Frankenstein is also the source of one of the shaping myths of modern culture, a cautionary tale in which a scientist in pursuit of truth but unfettered by morality is destroyed by his own creation. That most people encounter the story first through one of the numerous film versions adds a further mythic layer populated by visions of Boris Karloff’s monster and Peter Cushing’s mad doctor, of De Niro’s tragic outcast, Herman Munster, Bladerunner, and the Bride of Re-Animator to name a few of the many. In gothic terms, only the Dracula mythos is as culturally endemic.

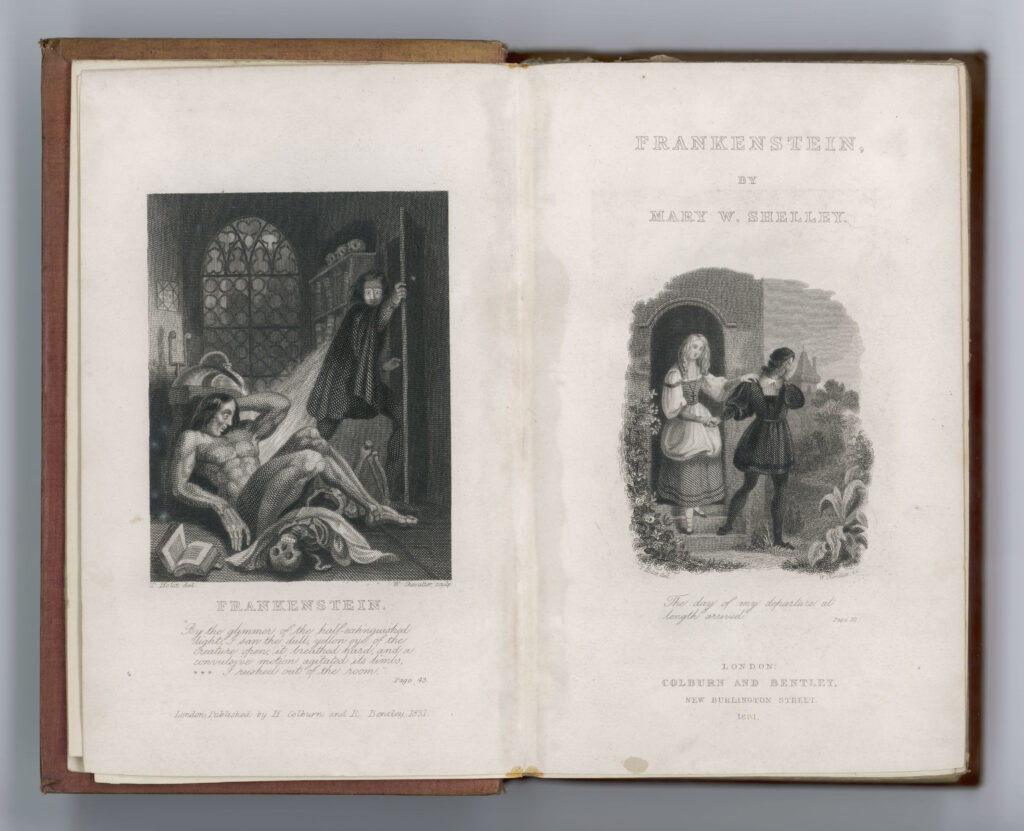

Frontispiece and Title Page to Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’

The novel itself also has a creation myth, inaugurated by Percy Shelley’s anonymous introduction to the first edition and expanded into a full narrative by Mary Shelley in her introduction to the Standard Novels edition of 1831. During the long Ranarök of 1816, the ‘Year Without a Summer’ when the world was enveloped in a nuclear winter following the eruption of Mount Tambora, Mary, along with Shelley and her half-sister Claire Clairmont were near neighbours and frequent guests of Lord Byron at the Villa Diodati on the shore of Lake Geneva. Along with Byron’s personal physician, the volatile John Polidori, they spent long evenings after dinner discussing literature, science, philosophy, and politics, and their days reading, unless the weather permitted a trip out onto the lake. ‘But it proved a wet, ungenial summer,’ wrote Mary, ‘and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house.’ One evening in mid-June, the party amused themselves by reading aloud stories from Fantasmagoriana, a French anthology of German ghost stories translated by Jean-Baptiste Benoît Eyriès in 1812. This led to a challenge from Byron that ‘We will each write a ghost story.’ Byron and Shelley soon tired of the game, the former producing ‘A Fragment’ of a gothic immortal story that Polidori later picked up and developed into ‘The Vampyre’ (1819). This was the first modern vampire story to seize the public imagination, turning the bloodsucking ghoul of European folklore into a sexually magnetic aristocrat, not a million miles from Byron in fact, and is therefore the second gothic icon to come out of the Villa Diodati. Shelley started something based on a childhood memory but, like Byron, soon abandoned it; Claire wrote nothing at all. Mary, however, persevered: ‘I thought and pondered – vainly … “Have you thought of a story?” I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.’

Mary had written in her later Introduction that ‘It is not singular that, as the daughter of two persons of distinguished literary celebrity, I should very early in life have thought of writing.’ As the daughter of the ‘English Jacobins’ William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, in love with Shelley and in awe of Byron, seeped in the narratives of European Romanticism from birth, the teenage Mary must have felt that her hour had come. The pressure must have been extreme. ‘In our family,’ her half-sister Claire once wryly said, ‘if you cannot write an epic poem or novel, that by its originality knocks all other novels on the head, you are a despicable creature, not worth acknowledging.’ And in life outside literature, though for Mary the two were always combined, she had already had two children by Shelley, the first, Clara, born the year before, living only eight days. She was presently nursing their son, William, born early in 1816. Shelley was still married to his first wife, Harriet, and Mary’s father had disowned the couple. (As an advocate of ‘Free Love’, Shelley was also in a sexual relationship with Claire, who in turn was carrying Byron’s child.) When she lost Clara, Mary had written in her journal: ‘Dream that my little baby came to life again – that it had only been cold and that we rubbed it by the fire and it lived – I awake and find no baby – I think about the little thing all day.’

Finally, it was a discussion of ‘natural philosophy’ that was the trigger for her story:

Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. They talked of the experiments of Dr. Darwin … Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.

In his Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion (1791), Erasmus Darwin – grandfather of Charles – had posited a ‘subtle fluid’ (animal electricity) as the source of motion and life. Italian physicist Luigi Galvani had discovered that an electrical spark could make a dead frog’s legs twitch. This process was developed by his rival Alessandro Volta, the inventor of the first chemical battery, who nonetheless named it ‘Galvanism’. Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini, performed a famous public demonstration of Galvanism on the corpse of the executed murderer George Foster at Newgate in 1803. The Newgate Calendar described the experiment:

On the first application of the process to the face, the jaws of the deceased criminal began to quiver, and the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion.

Mary was aware of this research, and Polidori had studied medicine in Edinburgh during the French wars when bodysnatching was rife to supply medical schools with corpses for dissection, a subject he was not coy about sharing. Thus, the original gothic discourse that had inspired Mary was fused with the morbid horrors of contemporary scientific reality, further fuelled by the laudanum that Byron and Shelley both took freely. This giddy cocktail resulted in a vivid waking dream:

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion…

At first terrified, Mary realised that she had found her ‘ghost story’. Shelley encouraged her to expand it into a novel and the first draft of Frankenstein was completed in the late Spring of 1817 when Mary was nineteen. It was published anonymously in three volumes by Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, & Jones of London on January 1, 1818. By this point, Shelley’s first wife had committed suicide and he and Mary had married. Reconciled with her father, Mary dedicated the novel to Godwin. Many critics, including Sir Walter Scott, erroneously attributed the book to Percy Shelley because of the dedication to his mentor. Conservative dislike of both Shelley and Godwin led to some damning reviews, such as the Quarterly Review’s dismissal of it as ‘a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity’. (When the second edition revealed Mary to be the author, she was attacked on the grounds of her gender.) But there were also very favourable notices, led by Walter Scott in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, who proclaimed it ‘an extraordinary tale, in which the author seems to us to disclose uncommon powers of poetic imagination.’ The novel was an immediate bestseller, and by 1823 Richard Brinsley Peake’s theatrical adaptation Presumption; or The Fate of Frankenstein cemented the myth, introducing hunchbacked henchmen ‘Fritz’ and pretty much all the trappings of James Whale’s Universal film version starring Colin Clive and Boris Karloff.

Elsa Lanchester and Boris Karloff in the 1935 film ‘Bride of Frankenstein’.

Though not as prolific as the film adaptations of Frankenstein itself, the story of the novel’s inception has also been retold in popular culture to the point of legend. James Whale used it to preface Bride of Frankenstein in 1935 (with Elsa Lancaster playing Mary and the monster’s ‘bride’), and Howard Brenton’s 1984 play Bloody Poetry inspired Ken Russell’s frenetic and surreal romp Gothic in 1986. This was followed by Rowing with the Wind directed by Gonzalo Suárez and Ivan Passer’s Haunted Summer (both 1988), and Roger Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound (1990), based on the novel by Brian Aldiss. More recently, there has been the movie Mary Shelley (2017), while Doctor Who took it on in ‘The Haunting of Villa Diodati’ (2020) in which Mary is inspired by a time-travelling cyberman. Although over-the-top, it is Russell’s Gothic that best captures the intensity of that summer. As Byron later wrote of it: ‘I was half mad between metaphysics, mountains, lakes, love unextinguishable, thoughts unalterable and the nightmare of my own delinquencies.’ Polidori’s diary notes that the party ‘talked till the ladies’ brains whizzed with giddiness’. For a teenage mother cut adrift from her father, grieving her first child, and trying to keep up with her married lover’s mood swings and wandering eye, it must have been incredibly hard work.

By the time of her introduction to the revised edition of 1831, Mary was a very different woman. Three of her four children were dead, as were Shelley, Byron, and Polidori, and Claire’s daughter by Byron, Allegra. As an established novelist, travel writer, biographer, and literary widow looking towards what was to become the Victorian era, her account of the novel’s conception, although surprisingly candid for one so private and reserved, is carefully managed, just as the text of the novel had been quietly revised to become less radical and more God-fearing, and just as she selected her late husband’s poetry for publication in a way that focused on his art and his love of nature over his atheism and radical politics. Ghost stories, Galvanism, and a nightmare did not alone make Frankenstein, just as there is more to it than the ‘creation destroys creator’ archetype so beloved by generations of filmmakers. By the time a very articulate ‘monster’ confronts his maker in one of the three intersecting narrative arcs that comprise the novel, you realise that it is far more interesting than this…

The basic premise of the novel was all contained in Mary’s dream. Having conceived the birth, she had continued:

Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handy-work, horror-stricken. He would hope that, left to itself, the slight spark of life which he had communicated would fade; that this thing, which had received such imperfect animation, would subside into dead matter; and he might sleep in the belief that the silence of the grave would quench for ever the transient existence of the hideous corpse which he had looked upon as the cradle of life. He sleeps; but he is awakened; he opens his eyes; behold the horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening his curtains, and looking on him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes.

Thus does Victor Frankenstein indeed reject his creation in horror and loathing, literally lying down in the hope that it will all go away. The creature regarding him in bed became the dark epiphany that concludes the ‘birth’ scene in the novel, those ‘watery, but speculative eyes’ asking the same things we all do of its maker: Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here? His creator’s response is to flee.

In opposition to her husband’s famously declared atheism, Mary was instantly aware that her protagonist was playing God, which would make the creature allegorically Adam, as suggested by the novel’s Miltonic epigraph, in which Adam addresses God like a petulant teenager:

Did I request thee, Maker, from my Clay

To mould me Man, did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?—

In effect, ‘I didn’t ask to be born.’ As the creature reminds Victor when they meet on Mont Blanc’s Mer de Glace: ‘Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed.’ The symbolic fluidity is immediately apparent. In a single line, the creature has shifted from Adam to Satan, a move emphasised by the setting; the Miltonic Hell is surrounded by a frozen wasteland:

Beyond this flood a frozen Continent

Lies dark and wilde, beat with perpetual storms

Of Whirlwind and dire Hail, which on firm land

Thaws not, but gathers heap, and ruin seems

Of ancient pile; all else deep snow and ice…

The novel’s climax, of course, takes place in the Arctic, further emphasising the ‘Satanic’ nature of not only Victor’s creation but Victor himself, another shifting symbol: Milton’s Satan, but notionally as imagined by the Romantics as a Promethean rebel against oppressive authority. As William Blake argued in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Milton ‘was a true poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.’ Percy Shelley similarly wrote in his Defence of Poetry that:

Nothing can exceed the energy and magnificence of the character of Satan as expressed in ‘Paradise Lost.’ It is a mistake to suppose that he could ever have been intended for the popular personification of evil … Milton’s Devil as a moral being is as far superior to his God, as one who perseveres in some purpose which he has conceived to be excellent in spite of adversity and torture…

But that’s not the whole story either.

Frankenstein is a gothic novel, and arguably the first example of modern science fiction. But it is not a genre piece so much as a key work of English Romanticism. It is, in fact, a Romantic novel about Romanticism. Mary was born into the revolutionary heart of the movement in 1797, the only child of the anarchist philosopher William Godwin and the feminist activist Mary Wollstonecraft. Like many Georgian radicals, Godwin’s background was non-conformist, and he was part of the English intelligentsia that embraced the French Revolution, that period of which Wordsworth wrote in The Prelude:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very Heaven! O times,

In which the meagre, stale, forbidding ways

Of custom, law, and statute, took at once

The attraction of a country in romance!

When Reason seemed the most to assert her rights

Godwin’s crowning contribution to this period had been his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793). Just as Rousseau was Democracy’s prophet, its sacred text his Social Contract, Godwin was the prophet of pure anarchism, his book a precise blueprint for a utopian society beyond leaders in which ‘man is perfectible’ and ‘susceptible of perpetual improvement’. As William Hazlitt wrote of him in this period, Godwin ‘blazed like a sun in the firmament of reputation … whenever liberty, truth, justice was the theme, his name was not far off.’ For Godwin, man was inherently rational. He argued that true political justice – transcending conservatism, aristocratic rule, religion, and the law – could be attained if all men followed the dictates of this reason over the repressive conventions of elite governments and monarchies. The following year, to illustrate his arguments dramatically and to reach a wider audience, Godwin wrote the allegorical gothic novel Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams, which explored the inequities of the State, particularly the class system and the law, through a tale of murder, false imprisonment, and relentless persecution after Caleb, a servant, discovers his master’s terrible secret. (It is nowadays considered to be an early if not the first example of detective fiction.) Mary had read this novel at least twice before she commenced Frankenstein, as well as Godwin’s Faustian St. Leon: A Tale of the Sixteenth Century (1799), in which the hero, like Caleb Williams, has his life ruined after gaining forbidden knowledge (in this case, the philosopher’s stone and the elixir vitae). Like Victor Frankenstein, Count Reginald de St. Leon sets out to help humanity, but instead brings only disaster on himself and those around him.

Godwin had first met Mary Wollstonecraft in 1787 through the radical publisher Joseph Johnson. Their paths crossed again in 1796 when Wollstonecraft returned to England after spending several years in Paris, where she had a daughter (Fanny) out of wedlock with the American adventurer Gilbert Imlay. Like Godwin, Wollstonecraft celebrated the French Revolution, which she viewed as the inevitable outcome of tyranny and as a vehicle for political progress. In 1790, she published A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a rebuttal of William Burke’s conservative attack on the liberal hopes for political reform in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. She followed this with the landmark feminist text A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), which argued for female emancipation through education and an ethical restructuring of societal norms. She and Godwin began a relationship, and though neither believed in the institution of marriage they did so to legitimise their unborn child. Although the birth appeared to go well, Wollstonecraft died eight days later of an infection. Wollstonecraft’s unconventional sex life, her association with radicals like Godwin and Thomas Paine, and her powerful attacks on the social and political status quo in England made her an easy target for the Establishment, a poster girl for the worst excesses of libertinism, atheism, and Jacobinism. Her reputation was not helped by Godwin’s candid biography Memoirs of the Author of the Vindications of the Rights of Women (1798), which refused to gloss over Wollstonecraft’s relationship with Imlay, their illegitimate child, or the fact that Mary had been conceived out of wedlock. Neither did Godwin’s reputation survive. By the turn of the century, the ‘Terror’ and the rise of Napoleon had turned even the truest Romantic believers like Wordsworth and Coleridge against the original ideals of the Revolution. Godwin’s Enquiry fell quickly out of favour and his star paled. Increasingly, money became a problem. As she never knew her mother, Mary found and loved her through the writing she had left behind, frequently visiting her grave at St Pancras Old Church.

Godwin did however retain one fan, who wrote to him in 1812 that:

It is now a period of more than two years since first I saw your inestimable book on Political Justice; it opened to my mind fresh and more extensive views; it materially influenced my character, and I rose from its perusal a wiser and better man … to you, as the regulator and former of my mind, I must ever look with real respect and veneration.

Then nineteen and recently sent down from Oxford over an atheist pamphlet, Percy Bysshe Shelley was the eldest son of the MP for Horsham (and later baronet). Although largely unpublished in his lifetime, his poetics and politics made him the direct heir to the revolutionary intellectuals of the 1790s like Godwin, who cultivated their friendship as much for Shelley’s family wealth as his adoration. A co-dependant relationship grew, with Shelley living off Godwin’s ideas and Godwin living off loans and gifts from Shelley. Shelley was soon captivated by Godwin’s sixteen-year-old daughter. They would meet in secret at her mother’s grave, where legend has it that their love was physically consummated. Shelley and Mary eloped to France in 1814, commencing a passionate and chaotic relationship fraught with debt, illness, and Shelley’s many infidelities, until he was drowned in the Bay of Spezia in 1822. ‘Shelley, the writer of some infidel poetry, has been drowned,’ announced the Tory newspaper the Courier, ‘now he knows whether there is God or no.’ Mary and her surviving son, Percy Florence Shelley, returned to England the following year, where she determined to make a living as a writer, a bold move for a woman in 1823.

In Frankenstein, we can read Mary’s heritage and her complex attitudes towards it. There is, for example, a lot of Shelley in Victor. Both are Promethean figures: visionary, rebellious, idealistic yet subject to bouts of intense self-pity, and captivated by the metaphysical intersection between Enlightenment science and alchemy. As a student, Shelley’s rooms had been as packed with scientific equipment as Victor’s and he was fascinated by electricity. Both men dream of achievable utopias, while locating Victor’s experiments in Ingolstadt link him to the Jacobin conspiracy believed to have begun in the city and which led to the French Revolution. Victor’s, and therefore by implication, Shelley’s idealism are then put to the test by Mary’s novel. Victor-as-Shelley and Shelley-as-Victor are brilliant and unique and passionate, but they are also careless, self-centred, impulsive, and dangerously reckless, with little thought given to the pain inflicted on their families in the process.

After Frankenstein was published, Shelley had left England in 1818 for good to escape its ‘tyranny civil and religious’ – he was pursued by government spies and debt collectors – leaving behind ‘Ozymandias’ and a pile of unpaid bills, and dragging Mary, Claire, and the children with him. Their third child, another Clara, died of fever on the road to Venice, Shelley having travelled ahead with Claire to visit Byron. The following year, Shelley registered the birth and baptism of a baby girl in Naples, Elena Adelaide Shelley, who was probably Claire’s child. (Left with ‘carers’, Elena died the following year.) William died in Rome the same year of suspected Malaria. ‘We have now lived five years together,’ wrote Mary, ‘and if all the events of the five years were blotted out, I might be happy.’ (It is notable that in Frankenstein the first victim is Victor’s brother William.) Around the time of Percy Florence’s birth, Shelley became infatuated with Sophia Stacey, the ward of one of his uncles, writing at least five love poems to her. A similar relationship began between the poet and Teresa (Emilia) Viviani, the daughter of the Governor of Pisa in 1820, the result being his poem Epipsychidion. (He still visited Claire too.) In 1822, Shelley became increasingly close to a married neighbour, Jane Williams, writing a series of love poems including ‘The Serpent is shut out of Paradise’ and ‘With a Guitar, to Jane’. Mary, meanwhile, had suffered a near-fatal miscarriage. An enthusiastic but inexperienced sailor, Shelley was soon dead, taking two shipmates with him.

Conceptually following her father’s Caleb Williams, the prototype ‘Romantic-Gothic’ novel, it is noticeable how the genre has evolved and modernised in Frankenstein. Mary was a voracious and critical reader and knew the eighteenth-century gothic form well. Her diaries were often little more than reading lists, and between 1814 and 1816 she notes having read The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Italian by Ann Radcliffe, and Matthew Lewis’ The Monk and his Romantic Tales. ‘Monk’ Lewis also visited the Shelley/Byron group in Switzerland in August 1816. In this older form of gothic narrative, settings were medieval – full of sublime landscapes and ruined castles – with a fairy tale division between good and evil in the narrative, characterised by an innocent and naive female protagonist and a melodramatic and sexually predatory villain. In addition to the human antagonist, there was often a supernatural or even demonic agency in play. Archetypally, these were ‘overcoming the monster’ stories, the threat to the hero being entirely external and always defeated in the end. Conversely, the Romantic-Gothic turns inward, heralding the later psychological horrors of Poe and Stevenson. Rather than Self versus Other, the threat becomes Self as Other with stories of madness and doppelgängers supplanting the more traditional gothic archetypes, which soldier on into the nineteenth century (and, indeed, our own), but as popular rather than literary narratives. This did not suit William Beckford, the author of the eighteenth-century gothic novel Vathek, who described Frankenstein as ‘perhaps, the foulest Toadstool that has yet sprung up from the reeking dunghill of the present times.’

Rebellious and rooted in Sturm und Drang, with a fascination for the hidden laws of Nature and an emphasis on imagination, emotion and, above all, individuality, Romantic visions of utopia and transcendence had always had a gothic undertow. (It is no accident that as well as reading Paradise Lost, Frankenstein’s creatures reads The Sorrows of Young Werther, Goethe’s landmark of German Romanticism.) The Romantic hero in fiction and fact was therefore already a half-gothic figure. Usually male, such an individual – artist, poet, warrior, lover, epic hero – stands apart from society and rarely finds his way back. He rejects all social restraint, particularly religious and political, valuing freedom, intellect, and creativity above all else. He is an outcast and an anti-hero, part-villain, part-victim, quick to draw on the defiant energy of the traditional gothic antagonist. As Byron wrote in Manfred (1817):

From my youth upwards

My spirit walked not with the souls of men,

Nor look’d upon the earth with human eyes

Wanderers, pariahs, and rebels, they roam the borders of society on doomed quests or as the bearers of terrible and dark knowledge like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, a key influence on Frankenstein:

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns;

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

In Frankenstein’s framing narrative, the explorer Captain Walton confesses that it was The Ancient Mariner that inspired him to explore the arctic: ‘I have often attributed my attachment to, my passionate enthusiasm for, the dangerous mysteries of ocean to that production of the most imaginative of modern poets.’ In finding Victor on the ice, who then teaches him his tale, Walton essentially meets the Ancient Mariner and is duly warned as Victor is compelled, like Coleridge’s original, to confess: ‘Unhappy man! Do you share my madness? Have you drunk also of the intoxicating draught? Hear me; let me reveal my tale, and you will dash the cup from your lips!’ As with the meeting between Victor and his creature on Mount Blanc, the icy hell of the Arctic Ocean is significant. In Romantic poetics and narratology, the sublime landscapes of the eighteenth-century gothic discourse remain, symbolising both the elemental power of nature – Shelley was writing Mont Blanc while Mary was writing Frankenstein – and the internal world of the tortured protagonist. Thus, the Romantics celebrated Milton’s Satan and Aeschylus’ Prometheus as transgressors and revolutionaries who pushed the boundaries of individual passion to extremes seeking forbidden knowledge. (Shelley would publish his own homage, Prometheus Unbound, in 1820.) As Shelley wrote in Alastor (1816):

…I have made my bed

In charnels and on coffins, where black death

Keeps record of the trophies won from thee,

Hoping to still these obstinate questionings

Of thee and thine, by forcing some lone ghost,

Thy messenger, to render up the tale

Of what we are.

A year later, Byron’s Manfred would similarly seek arcane answers to the meaning of life and death:

And then I dived,

In my lone wanderings, to the caves of death,

Searching its cause in its effect; and drew

From wither’d bones, and skulls, and heap’d up dust,

Conclusions most forbidden.

Victor Frankenstein, of course, also researches mortality in graveyards:

Darkness had no effect upon my fancy, and a churchyard was to me merely the receptacle of bodies deprived of life, which, from being the seat of beauty and strength, had become food for the worm. Now I was led to examine the cause and progress of this decay and forced to spend days and nights in vaults and charnel-houses.

This is a nod to both contemporary scientific research – resurrection men and anatomists – and to necromancy, linking Victor’s gothic self (who reads Agrippa and Paracelsus) to his Enlightenment medical student persona, who seeks to ‘penetrate the secrets of nature’ by combining modern empiricism with the older narrative of alchemy. Here, the trappings of the old gothic cease. In an eighteenth-century gothic novel, the heroine of sensibility and the moral values she represents are protected by benevolent male authority figures like her father and her priest, and she is ultimately saved by a hero that she may well marry, like a prince in a fairy tale, restoring patriarchal balance after all that scary and sexually threatening violence. In Frankenstein, Victor, who should be the hero/protector of Elizabeth’s heroine instead creates the monster that murders her – just as Milton’s Satan gives birth to Death – which is in turn his own terrible double as evidenced by his regular lamentations that he has murdered his brother, his best friend, Justine Moritz and so forth, the catalyst for this awful chain of events being his experiment. This doubling remains in the modern myth, through the common conflation of the name ‘Frankenstein’ to represent both creator and creature.

Like Godwin, Wollstonecraft, and Shelley, Victor is an optimist (at the start of his journey, at least), who believes his work will ‘banish disease from the human frame and render man invulnerable to any but a violent death!’ (In his hubris, like Walton, he labours not for wealth but for ‘glory’.) His idealism mirrors that of Mary’s parents and lover, who all recklessly believed in humanity’s capacity to learn, change, and grow. Just as the Jacobin vision of Liberté, égalité, fraternité collapsed into Terror then dictatorship and endless war, many of the original revolutionaries subsequently going to the guillotine, Victor’s dream shoves him into a nightmare. In this, one of many allegories in the novel, the creature becomes the mob, the raging proletariat wound up by intellectuals who turn first on their class enemy but then continue to blindly destroy just as Frankenstein’s creature relentlessly kills everyone his ‘father’ loves. (He’s also Satan, Adam, Eve, Frankenstein’s double – or his Jungian ‘shadow’ – and Rousseau’s ‘noble savage’.) This, in turn, is an elegant reading of Godwin’s Rousseau-inspired thesis that man is born into an unfallen state of innocence that can be either nurtured or corrupted by society. In his Enquiry, one of the many examples he offers is that of crime, writing that:

The superiority of the rich, being thus unmercifully exercised, must inevitably expose them to reprisals; and the poor man will be induced to regard the state of society as a state of war, an unjust combination, not for protecting every man in his rights and securing to him the means of existence, but for engrossing all its advantages to a few favoured individuals and reserving for the portion of the rest want, dependence and misery.

Godwin believed that a new social system based not on class, law, and government but ‘universal benevolence’ could create a just and virtuous society, this ‘virtue’ naturally emerging from the exercise of pure reason and free will. Thus enlightened, society would shed superstition (religion), despotic government, and the property fetishism attached to marriage and inheritance. This was all in opposition to the seventeenth-century political philosophy of Thomas Hobbes, whose theories affirmed the legitimacy of state authority over the ‘self-interested’ individual. This is the main point of the creature’s narrative in Frankenstein, which alongside Walton’s frame and Victor’s confession constitute the points of view of the text. As the creature becomes self-aware while secretly observing the poor family of Felix, Agatha, and their blind father, his ‘natural’ inclination is to help them. As he tells his creator, ‘I was benevolent; my soul glowed with love and humanity.’ Shunned and abused, however, because of his monstrous appearance by everyone he meets, including the family he has aided, his love turns to hate for ‘them that abhore me.’ And this includes Frankenstein, who rejected him at birth: ‘You, my creator, abhor me; what hope can I gather from your fellow creatures?’ The creature repeatedly uses Godwin’s key word in this dialogue, seeking only ‘justice’ from his creator, a mate of his own kind: ‘Do your duty towards me, and I will do mine towards you and the rest of mankind.’ Frankenstein again fails him, fearing that ‘a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.’ From then on, his creature wants only vengeance followed by oblivion. With the exception of Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), the creature never speaks in the movies. Ironically, the narrative that underpins a significant part of Mary’s moral and political argument has been removed from the mythology in favour of a return to ruined castles, damsels in distress, and monsters to be overcome. Milton has gone, as has Godwin, just as the latter’s theory of ‘Political justice’ was swept away by human nature and history.

Finally, as with Victor’s notable resemblance to Shelley, it’s difficult to decide whether Mary is supporting her father’s philosophy or critiquing it. The answer is probably both, which doesn’t stop the novel also being a sharp indictment of masculine ambition directed at both her father and her husband. It’s also an allegory of the horrors of giving birth and the responsibilities of parenthood, both matters that greatly preoccupied the young Mary, who repeatedly offers family as an antidote to Victor’s individualism in the novel and, indeed, the creature’s resentment and violence. Perhaps with a bride he would have turned out alright… As gothic filmmaker Guillermo del Toro has said, Frankenstein is also the ‘quintessential teenage book … You don’t belong. You were brought to this world by people that don’t care for you and you are thrown into a world of pain and suffering, and tears and hunger’, which brings us back to Milton’s God and Adam and ‘I didn’t ask to be born.’ But this is why reading Frankenstein is so much fun. You approach it with all these preconceptions based on the movies, and then encounter something quite different but just as spine-chilling and page-turning. And in what appears to be a notionally simply fable about the dangers of playing God, you find a very brilliant young woman’s often conflicted feelings about herself in the world, her relationships, and the era – political and literary – in which she finds herself. And in this sense, she is the creature, her ‘hideous progeny’, once more asking those big scary questions: Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here?

Main Image: Boris Karloff as the monster in the 1931 film Frankenstein Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Above Top: Frontispiece and Title Page to Mary Shelley’s novel, first published 1818 Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Above Bottom: Bride of Frankenstein 1935 American science-fiction horror film, starring Boris Karloff as The Monster and Elsa Lanchester in the dual role of Mary Shelley and the Monster’s bride Credit: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

Frankenstein (Collector’s Edition)

Mary Shelley