Book of the Week: Middlemarch

George Eliot’s Middlemarch is set in the period of the 1832 Reform Act and general election. Sally Minogue uncovers some similarities with the present.

George Eliot’s Middlemarch is a compendious novel, generous in its sweep, with a cast of characters of near-Dickensian proportions (though Eliot is an entirely different kind of novelist), taking in Italy as well as England, with a wide and powerful moral and emotional span, and set at a time of great importance in English history. Yet Eliot gave it the subtitle ‘A Study of Provincial Life’. Henry James, reviewing it, pronounced it ‘too copious a dose of pure fiction’ – and he was no slouch in being copious. But James’s objection was to that very provincialism that Eliot marks out as significant in her subtitle. He couldn’t understand, for example, why Fred Vincy, ‘this common-place young gentleman, with his somewhat meagre tribulations’ should be of any interest to us, or indeed to his creator. As far as he was concerned, all those less elevated parts might have been cut out. So where do we place ourselves as readers when we approach a novel such as this, both large in its scope but insistently turning its gaze to the small, the overlooked – the provincial?

‘Provincial’ has always carried pejorative associations, even when used descriptively. It suggests that which is parochial by virtue of its very geography. The provinces, from which the adjective derives, are strictly defined as those parts of a country which lie beyond its capital city, and thus outside the realms of power. This is no longer quite accurate in England with its city mayors and its major and influential conurbations – we wouldn’t describe Manchester as provincial. I’m not sure it would have been so described in the later 19th century either, even if it did qualify as belonging to the provinces. Elizabeth Gaskell set two major novels, Mary Barton and North and South in actual or fictional versions of Manchester, and though she focuses on working class life, especially in Mary Barton, her concerns are not provincial but take in the large-scale social changes wrought by industrialisation. Eliot by contrast places the provincial at the forefront by setting her novel not in any of the large industrial cities she could have chosen, but in a relatively small Midlands town, Middlemarch, its very name redolent of the average, the unobtrusive, that which lacks influence. This is what James can’t see the point of, and what, for Eliot, is the point.

The politics of power do impinge on Middlemarch in the form of the historically significant period 1831-32, when the movement for Reform and the seesaw progress of the Reform Act caused Parliamentary uproar and popular disturbance. Now this choice by Eliot for the historical and political context of her novel likewise speaks to her theme, since the Reform Act when it was eventually passed made major changes in electoral representation, generally producing a fairer distribution of voting power, getting rid of certain corrupt elements such as rotten boroughs with very small electorates but still represented by one or more Members of Parliament, and recognizing the importance of representation for the populous cities which had sprung up in the Industrial Revolution. It extended suffrage (though still only to men, and limited to householders and certain tenants) and introduced a system of voter registration. While there are competing views as to the scale of the effectiveness of the 1832 Reform Act, there is no doubt that it led to a fairer representation of the populace in Parliament and a more balanced distribution of democratic power.

The politics of power do impinge on Middlemarch in the form of the historically significant period 1831-32, when the movement for Reform and the seesaw progress of the Reform Act caused Parliamentary uproar and popular disturbance. Now this choice by Eliot for the historical and political context of her novel likewise speaks to her theme, since the Reform Act when it was eventually passed made major changes in electoral representation, generally producing a fairer distribution of voting power, getting rid of certain corrupt elements such as rotten boroughs with very small electorates but still represented by one or more Members of Parliament, and recognizing the importance of representation for the populous cities which had sprung up in the Industrial Revolution. It extended suffrage (though still only to men, and limited to householders and certain tenants) and introduced a system of voter registration. While there are competing views as to the scale of the effectiveness of the 1832 Reform Act, there is no doubt that it led to a fairer representation of the populace in Parliament and a more balanced distribution of democratic power.

So this in one sense speaks to George Eliot’s emphasis on the unconsidered, those beyond the realms of power, since the impetus behind the Reform Act was to bring them more closely into the realms of power. But Eliot has no illusions about the process; Dorothea’s uncle and guardian, Mr Brooke, fancies himself as a Reform candidate in the forthcoming 1831 election (which took place part way through the process of attempting to pass the Reform Act). This election is introduced thus by Eliot, halfway through the novel:

The doubt hinted by Mr Vincy whether it were only the general election or the end of the world that was coming on … was a feeble type of the uncertainties in provincial opinion at that time. With the glow-worm lights of country places, how could men see which were their own thoughts in the confusion of a Tory ministry passing Liberal measures … (Chapter 37)

The ironic tone of ‘the general election or the end of the world’ is carried on in ‘the glow-worm light of country places’. This is not to be a serious analytic account of Reform politics. Instead Eliot is once more guiding us to the ‘provincial’ viewpoint, to see these great movements (as they undoubtedly were) played out on the smaller and somewhat comic stage of the Middlemarch hustings. For Mr. Brooke, with his blustering, uninformed support of ‘Reform’, actually has very little notion of what he is committing himself to. In his own position and practice as a landlord he embodies everything the Reform Act would oppose. As he hedges his bets, his aide Will Ladislaw has to keep reminding him of the reality:

‘Only I want to keep myself independent about Reform, you know. I don’t want to go too far … But of course I should support Grey.’

‘If you go in for the principle of Reform, you must be prepared to take what the situation offers,’ said Will. ‘If everybody pulled for his own bit against everybody else, the whole question would go to tatters.’

‘Yes, yes, I agree with you – I quite take that point of view. I should put it in that light … But I don’t want to change the balance of the constitution …’

‘But that is what the country wants,’ said Will. (Chapter 46)

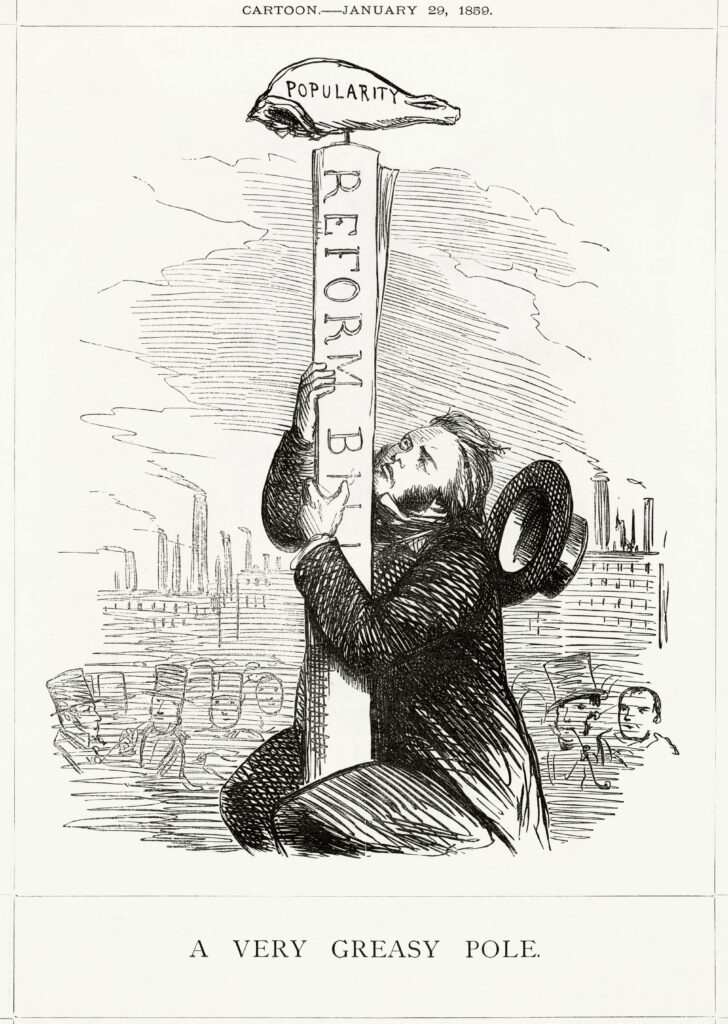

A Very Greasy Pole (John Bright).

Brooke wants to have his cake and eat it; he’ll support Reform, but ‘not too far’, he’ll argue for change, but not to ‘the balance of the constitution’. He wants to win the nomination, but without having to think too hard about it, or indeed believe in what he says; someone else can do both of those things for him. And whenever Ladislaw (the one who is doing those things for him) tries to keep him to the right political path, ‘he always agreed with [him] … but after an interval the wisdom of his own methods reasserted itself, and he was again drawn into using them with much hopefulness’. He wants power, but without making any changes to his own thinking or practice. (Ring a bell?)

Will Ladislaw tries to keep his own conscience whilst distancing himself from his man’s methods for enlisting the Middlemarch voter ‘on the side of the Bill – which were exceedingly similar to the means of enlisting [him] on the side against the Bill.’ It’s Will’s role to provide Brooke with the arguments for Reform that elude him if left to himself:

[Will] had written out various speeches and memoranda for speeches, but he had begun to perceive that Brooke’s mind, if it had the burthen of remembering any train of thought, would let it drop, run away in search of it, and not easily come back again. To collect documents is one mode of serving your country, and to remember the contents of a document is another. No! the only way in which Mr Brooke could be coerced into thinking of the right arguments at the right time was to be well plied with them till they took up all the room in his brain. But here there was the difficulty of finding room, so many things having been taken in beforehand. Mr Brooke himself observed that his ideas stood rather in his way when he was speaking. (Chapter 51)

Brooke is in fact an acute delineation of a politician just like Boris Johnson: short on moral commitment, short on grasp of detail, unable to master a brief, and so unable to present an argument accurately – but with his confidence unmarred by these failings since he is also short on self-reflection.

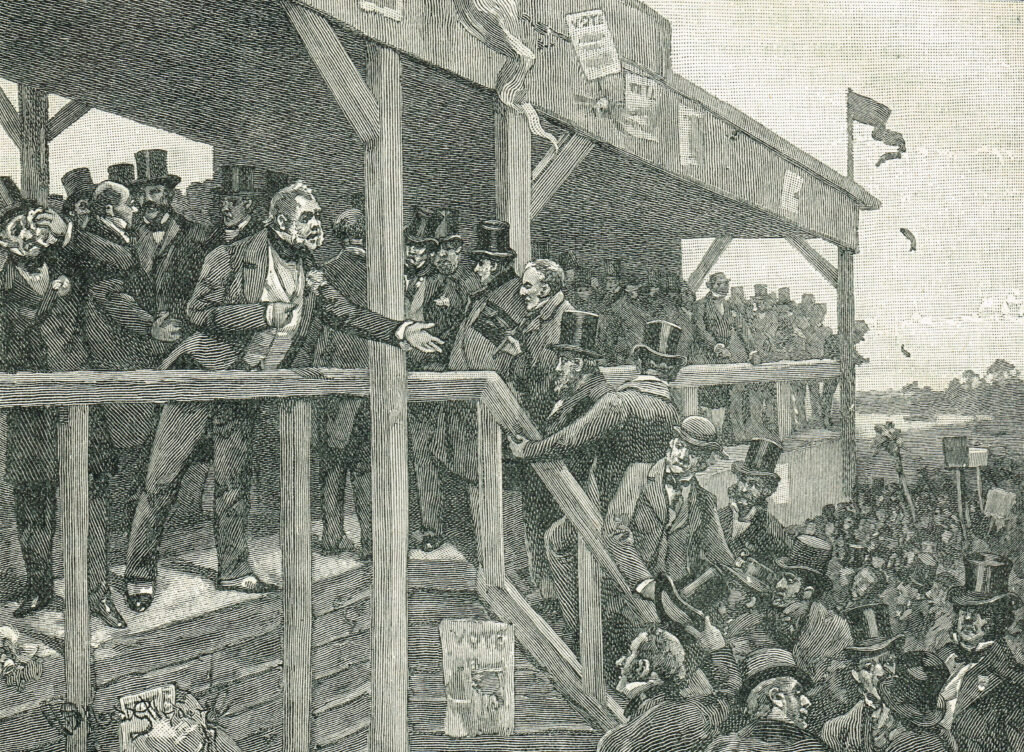

Unlike his contemporary equivalent, however, Brooke comes to grief at the hands of the people, in a fine comic scene on the hustings. Brooke begins, as he always does, cheerfully – ‘It was a fine May morning and everything seemed hopeful’; when an element of uncertainty does approach, he keeps his spirits up with, well, spirits. Then stepping on to the balcony of The White Hart, he goes to pieces. ‘The pat opening had slipped away … Ladislaw thought, “It’s all up now. The only chance is that, since the best thing won’t always do, floundering might answer for once.”’ But for Brooke, floundering doesn’t answer, and he is finally undone by an effigy of himself in the crowd, and a ventriloquist voice which takes his phrases and mimics and mocks them. When eggs start to fly, Brooke retreats. And – again, unlike the case with our erstwhile leader until he was dragged kicking and screaming from office – ‘deputations without and voices within had concurred in inducing that philanthropist to take a stronger measure than usual for the good of mankind; namely to withdraw in favour of another candidate.’[1]

The irony in the narrative voice may seem a touch heavy; we know that Brooke’s motives are selfish rather than altruistic. But Eliot, in general a compassionate narrator, allows him to slip away from his ill-conceived venture with a certain good-heartedness intact. His pursuit of power is fleeting and he’s not prepared to make many personal sacrifices for it: he is a silly man, not a bad one. Our author’s view of politics in general has a harder edge:

Occasionally Parliament, like the rest of our lives, even to our eating and apparel, could hardly go on if our imaginations were too active about processes. There were plenty of dirty-handed men in the world to do dirty business.

In the shifting way of the omniscient narrator, and especially this one, Eliot places this thought partly in Will Ladislaw’s mind, partly in her own, and partly in the reader’s, through that complicit, repeated ‘our’. We too are to blame if ‘dirty-handed men’ get their way, since sometimes we avert our gaze.

Eliot’s focus on the election and the political process in general takes up but a small part of Middlemarch, precisely because her interest lies elsewhere, in the areas Henry James found so tedious. But in those few passages we see her acute observational eye trained almost as a political cartoonist’s would be, on the way outer behaviours can speak of inner failings. As a novelist, and in the generous form that this novel took, she can then move us inside her characters even as she skewers them. As a result, we can’t help but have a moment of sympathy for Brooke when he finds himself so adrift from the speech he had imagined – but then he had only imagined it.

Eliot treats her politicians as she treats all of her characters: worthy of her interest and compassion, whilst observing them with a very clear eye. They are for the most bit players in a novel more interested in the workings of the human heart and mind, but placed thus, they form part of that tapestry of ‘unhistoric acts’ which George Eliot saw as the central force of her novel – the provincial life in its fullest sense.

George Eliot’s major novels are published by Wordsworth editions, as are Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton and North and South.

[1] That did famously happen once of course, Johnson withdrawing in favour of Michael Gove in the 2016 post-Brexit referendum Tory leadership contest, an action whose aetiology is still something of a mystery, though we can safely say the good of mankind was not involved.

Main image: Arbury Farm, birthplace of George Eliot Credit: FAY 2018 / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Scene at the hustings, in the days of Open election Credit: Historical Images Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: A Very Greasy Pole (John Bright) Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on the life and works of George Eliot, visit: George Eliot Fellowship

Books associated with this article