Houdini and Doyle: A Modern Ghost Story

Part One: Atlantic City, 1922

Some of you may recall a few years back a TV series entitled Houdini and Doyle. Created by David Hoselton (previously a staff writer on House) and David Titcher (the creator of The Librarian fantasy franchise), the show used the real friendship between the famous author and the equally famous magician as a springboard for a kind of Edwardian X-Files. The pair investigated mysteries that may or may not have been paranormal in origin, the hook being the tension between Conan Doyle’s spiritualist beliefs and Houdini’s practical scepticism. The show was neither critically or commercially successful and was cancelled after one season in 2016. While Stephen Mangan (Doyle) and Michael Weston (Houdini) charged around investigating murderous ghosts, demons, vampires (and yes, Bram Stoker was in that one), and, in one case, alien abduction, I remember thinking how much more interesting the real story behind their friendship still was. This story was more tragedy than fantasy; a story of love, grief, and betrayal played out in the murky world of mediums and paranormal investigators during the revival of interest in Spiritualism that followed the First World War. It is a ghost story which manages at once to be gothic yet not at all supernatural, in which two brilliant but very different men discovered the limits of friendship where faith is concerned.

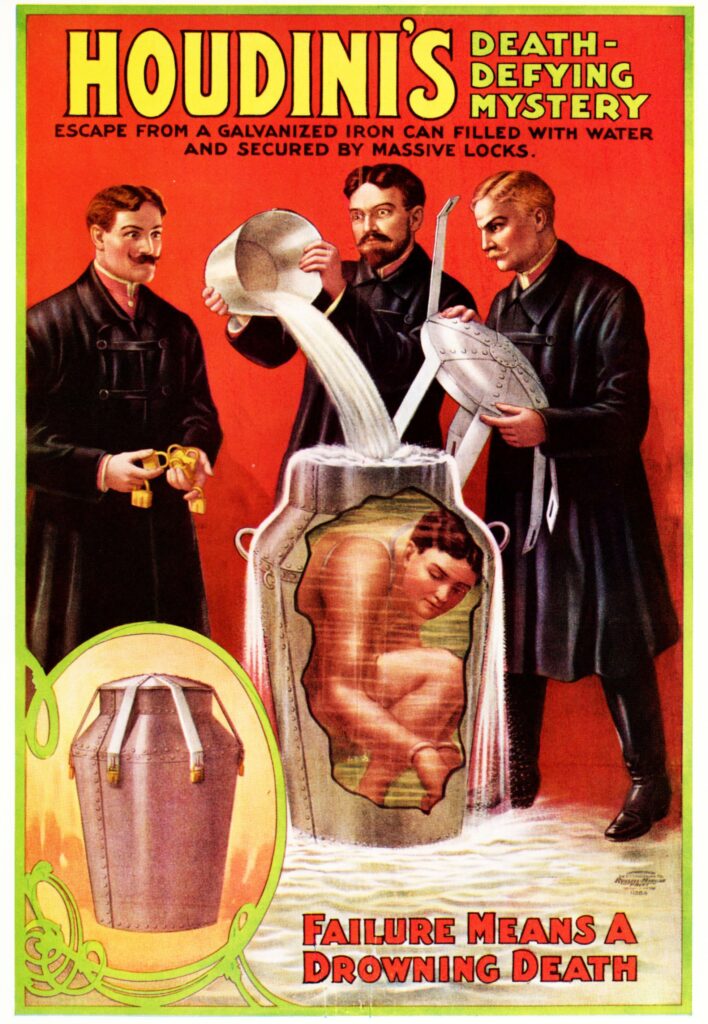

Harry Houdini poster from the 1910s

Celebrity friendships, like their romances, are strange beasts. Often, the unifying feature is the celebrity itself, which can bring otherwise very different people together, such as, you might think, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and ‘The Handcuff King’ Harry Houdini (born Erik Weisz) – a strange meeting of the famous British author and a Hungarian-American illusionist and escapologist. Notionally, these are strange bedfellows indeed, but for the fact that both were very high-profile commentators on Spiritualism and the possibility of talking to the dead. Conan Doyle was a true believer, Houdini was not, although he was willing to be if presented with undeniable evidence. As both men published on the subject, and were, in fact, probably the two most famous names associated with Spiritualism in their day, it was inevitable that their paths would cross. They began a correspondence triggered by their independent investigations of the French medium Eva Carrière (Conan Doyle was convinced ‘Eva C’ was genuine, Houdini that she was using perfectly explicable magician’s trickery). They met in 1920 when Conan Doyle attended a performance by Houdini at the Brighton Hippodrome and invited the magician and his wife to stay at his family home in Crowborough. Their shared fascination for Spiritualism created an instant bond, and their early correspondence and published reminiscences demonstrate that each man had great affection and respect for the other, despite their fundamental differences of opinion and strikingly different backgrounds. Conan Doyle held Batchelor’s, Masters, and Doctoral degrees in medicine and was a knight of the realm. He was every inch the Edwardian gentleman of letters. Houdini was a working-class immigrant; he was highly intelligent but had received virtually no formal education. Everything he knew was learned on the road in travelling carnivals. As Houdini wrote in A Magician Among the Spirits (1924), ‘We do not believe the same thing.’

This disconnect was in part reconciled, at least on Conan Doyle’s side, by his belief that Houdini’s exploits could not be tricks and misdirection but were genuine examples of psychic phenomena. The more Houdini denied this, the more Conan Doyle felt that this denial was an elaborate cover for the truth, that Houdini was a true psychic medium who pretended to be a magician, his audience ‘bluffed by the commercialization of psychic power.’ (Houdini’s position was that for most if not all mediums the reverse was the case.) When Houdini appeared to walk through a wall or escaped from a buried coffin or a tank full of water, Conan Doyle was convinced he had physically dematerialised. As he wrote in ‘The Riddle of Houdini’ (1930): ‘Who was the greatest medium-baiter of modern times? Undoubtedly Houdini. Who was the greatest physical medium of modern times? There are some who would be inclined to give the same answer.’

Although Conan Doyle will forever be associated with his most famous creation, Sherlock Holmes – a character he once described as ‘this monstrous growth’ – it was his commitment to the Spiritualist cause that he felt was ‘far more serious.’ It was, he said, ‘The highest purpose that I could possibly devote the remainder of my life to.’ If you watch his 1927 Fox Newsreel interview, you’ll see he can’t wait to get through the inevitable questions about Holmes to arrive at what he really wants to talk about, his Spiritualist calling. Conan Doyle had always had an interest in the paranormal and had publicly declared himself to be a Spiritualist in the College of Psychic Studies journal Light in 1887. A founder-member of the Hampshire Society for Psychical Research in 1889, he joined the Society for Psychical Research in 1893, and the following year investigated poltergeists in Devon with the renowned ghostbuster Frank Podmore. In the early twentieth century, Conan Doyle was part of a triumvirate of Establishment British Spiritualists along with the crusading journalist W.T. Stead (who established a ‘spiritual telegraph’ between the departed, mediums and clients before going down on the Titanic), and the physicist Sir Oliver Lodge, whom Doyle had known well since they met in an anteroom at Buckingham Palace awaiting their knighthoods in 1902. During the Great War, Conan Doyle became convinced that Spiritualism was sent by God to bring solace to the bereaved and in 1918 he published his first book on the subject, The New Revelation, the year his dead son Kingsley supposedly came through at a family séance and congratulated his father on the ‘Christ-like message you are giving to the World.’ Kingsley had died of pneumonia after being seriously wounded at the Battle of the Somme, and Conan Doyle had also recently lost his brother, Brigadier-general Innes Doyle (also from pneumonia). After the war he devoted a large part of the rest of his life to spreading the word in lecture tours across Britain, Europe, and America.

For Houdini, conversely, Spiritualism had always been a hustle. He had first found his way to table-tapping when he was still a struggling carney in the 1890s, giving a fake séance as part of his act, in which, his playbill promised:

When conditions are favourable, tables float through the air and musical instruments playing sweetest music are seen floating through space; all the spirit hands are seen in full light.

Such events were common features of any ‘real’ séance, and as an accomplished conjuror, Houdini knew from the start exactly how the ‘mediums’ were doing it. To add further authenticity to his performance, the ads also noted that ‘A committee of businessmen have kindly volunteered to act as an investigating committee, which will insure honesty of purpose.’ With a pantomime wink, this followed the tradition of ‘impartial’ and ‘scientific’ observers – many of them highly respected figures, such as Podmore, Stead, Lodge and Conan Doyle – that attached themselves to noted mediums to prove (or disprove) their powers, a process that dated back to the Fox sisters and the early days of the Spiritualist craze in the 1850s. ‘To me,’ he later admitted, ‘it was a lark,’ but this attitude profoundly changed with the death of his beloved mother, Cecelia, in 1913:

As I advanced to riper years of experience I was brought to a realization of the seriousness of trifling with the hallowed reverence which the average human being bestows on the departed, and when I personally became afflicted with similar grief I was chagrined that I should ever have been guilty of such frivolity and for the first time realized that it bordered on crime.

Houdini idolised his mother and longed to contact her from beyond the grave. He was prepared to believe that this was possible, he wanted to believe it was possible, but first he had to be convinced. But however strong their reputations among the faithful, every medium Houdini consulted turned out to be a fraud, whose ‘manifestations’ he could easily reproduce using his own stagecraft. As he finally conceded:

As a result of my efforts I must confess that I am farther than ever from belief in the genuineness of Spirit manifestations and after twenty-five years of ardent research and endeavor I declare that nothing has been revealed to convince me that intercommunication has been established between the Spirits of the departed and those still in the flesh.

For Conan Doyle, however, Houdini felt it was ‘a case of religious mania’:

Sir Arthur believes implicitly in the mediums with whom he has convened and he knows positively, in his own mind, they are all genuine. Even if they are caught cheating he always has some sort of an alibi which excuses the medium and the deed. He insists that the Fox sisters were genuine, even though both Margaret and Katie confessed to fraud … He is good natured, very bright, but a monomaniac on the subject of Spiritualism. Being uninitiated in the world of mystery, never having been taught the artifices of conjuring, it was the simplest thing in the world for anyone to gain his confidence to hoodwink him.

This is clear from Conan Doyle’s own comments on Houdini’s escapes, which he considered utterly impossible:

If I put a beetle in a bottle, hermetically sealed, and that beetle makes its escape, I, being only an ordinary human, and not a magician, can only conclude that either the beetle has broken the laws of matter, or that it possesses secrets that I should call supernormal … Such results can only be obtained by the passage of matter through matter … and though such a thing may seem inconceivable to the prosaic scientist of to-day, he would have pronounced wireless or flying to be equally impossible a generation or so in the past.

And so, despite a thriving if strange friendship, these opposing viewpoints moved inexorably towards collision.

In June 1922, Conan Doyle and his family were holidaying in Atlantic City on a break from an American lecture tour, so they invited the Houdinis to join them. One afternoon, Conan Doyle asked Houdini if he’d be willing to attend a ‘special séance’ with Lady Doyle, ‘as she has a feeling that she might have a message come through.’ Houdini’s wife, Bess, had a shrewd idea who this message might be from. Using a series of secret signs the pair had developed years before for a mind-reading act, she told Houdini she had discussed his mother with Jean Doyle the previous evening. Jean Doyle (née Leckie) was Conan Doyle’s second wife. Although not a Spiritualist when they married, the intensity of her husband’s belief ultimately converted her to the extent that she developed her own medial powers in the form of automatic writing. The séance was held in the Doyle’s suite at the Ambassador Hotel on June 17, Houdini’s mother’s birthday. Lady Doyle was soon ‘seized by a spirit’. Her hands shook uncontrollably, she pounded upon the table, and entreated the spirits to pass on a message. The forces, said Conan Doyle, had never manifest themselves so strongly. ‘Do you believe in God?’ asked Jean, her voice trembling. Her hand beat upon the table three times: Yes. ‘Then I will make the sign of the cross,’ said Jean, marking the paper. Her right hand jerked in spasm and began to write. As each page was finished, Conan Doyle tore it from the pad and handed it to Houdini:

Oh, my darling, thank God, thank God, at last I’m through – I’ve tried, oh, so often – now I am happy. Why, of course I want to talk to my boy – my own beloved boy – Friends, thank you, with all my heart for this.

You have answered the cry of my heart – and of his – God bless him – a thousandfold for all his life for me – never had a Mother such a son – tell him not to grieve, soon he’ll get all the evidence he is so anxious for – Yes we know – tell him I want him to try and write in his own home. It will be far better so.

I will work with him – he is so, so dear to me – I am preparing so sweet a home for him in which some day in God’s good time he will come to it, is one of my great joys preparing for our future –

I am so happy in this life – it is so full and joyous my only shadow has been that my beloved one hasn’t known how often I have been with him all the while, all the while – here away from my heart’s darling-combining my work thus in this life of mine.

It is so different over here, so much larger and bigger and more beautiful – so lofty – all sweetness around one – nothing that hurts and we see our beloved ones on earth – that is such a joy and comfort to us –Tell him I love him more than ever – the years only increase it and his goodness fills my soul with gladness and thankfulness. Oh, just this, it is me. I want him only to know that – that – I have bridged the gulf – that is what I wanted, oh, so much – Now I can rest in peace –

The message continued in this vein, saying much but saying nothing, the way that such ‘spirit messages’ usually do, Houdini later noting that, ‘I sat serene through it all, hoping and wishing that I might feel my mother’s presence. There wasn’t even a semblance of it.’

Then the trance was over. As the ‘spirit’ had suggested Houdini try automatic writing himself, he obliged the Doyles by taking up the pencil to see if anything might come and wrote the first thing that popped into his head, which was the name ‘Powell’. The effect on Conan Doyle was, he wrote, ‘like an electric shock.’ Conan Doyle’s account of the séance explains why:

My friend, Ellis Powell, had just died in England, so the name had a meaning. ‘Why, Houdini,’ I cried, ‘Saul is among the prophets! You are a medium.’ Houdini had a poker-face and gave nothing away as a rule, but he seemed to me to be disconcerted by my remark. He muttered something about knowing a man called ‘Powell’ down in Texas, though he failed to invent any reason why that particular man should come back at that particular moment. Then, gathering up the papers, he hurried from the room.

Ellis Powell had been the editor of the Financial News and an ardent champion of Spiritualism (‘my fighting partner’ Conan Doyle called him). Frederick Eugene Powell, on the other hand, was an American magician with whom Houdini was corresponding over a business deal. He was also the subject of an on-going if light-hearted argument between Houdini and Bess as to whether Powell should replace his sick wife with another assistant while on tour. Ever the pragmatist, Houdini saw nothing wrong in this, but Bess thought it might upset Powell’s wife, especially if the assistant was younger.

To Conan Doyle, the séance had been conclusive: Houdini’s mother had come through, and when Houdini took up the pencil, Ellis Powell had tried to communicate. Houdini was less than convinced. Why had the ‘spirit’ not mentioned the fact that it was her birthday? (Conan Doyle’s response was that this was irrelevant: ‘What are birthdays on the other side? It is the death day which is the real birthday.’) How had his dear mother, who never learned English, been able to communicate so fluently in that language after her demise; and why would his mother, like him a Hungarian Jew, consent to the marking of the paper with a cross? As to the subsequent ‘Powell’ reference, this was an easily explained coincidence. Conan Doyle was having none of this, writing to Houdini:

No, the Powell explanation won’t do. Not only is he the man who would wish to get me, but in the evening, Mrs. M., the lady medium, got ‘There is a man here; he wants to say that he is sorry he had to speak so abruptly this afternoon’.

As to Houdini’s other objections, the language could be explained away as ‘a rush of thought which is translated in coming’ while the cross was simply a symbol of protection to ‘guard against lower influences.’ What decent spirit, of any creed, could object to that? Conan Doyle went on to assert that Houdini at the time was ‘deeply moved, and there is no question that at the time he entirely accepted it.’ It was only, he claimed, when he published an account of the incident in Our American Adventure that Houdini ‘had to explain it away to fit it into his anti-Spiritualistic campaign.’

Correspondence on the subject ceased soon after, both men agreeing to close the matter and move on. But the damage had been done. For Conan Doyle, the ungrateful Houdini was stubbornly rejecting absolute proof and insulting Jean’s powers; for Houdini, the Doyles had made a mockery of his deepest feelings for his mother. As even Conan Doyle later admitted, ‘His love for his dead mother seemed to be the ruling passion of his life.’ Though each tried, the friendship quickly cooled and the next time they crossed swords over Spiritualism it was as fully fledged adversaries…

Main image: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Image in text: Houdini poster from the 1910s. Credit: Retro AdArchives / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes & His Last Bow (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Return of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

A Study in Scarlet & The Sign of the Four (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle