Houdini & Doyle – Part Two

Part Two: Boston, 1924

Growing increasingly bitter in his grief, Houdini never tired of exposing mediums, even while touring at the height of his fame. As he told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times, ‘It takes a flimflammer to catch a flimflammer.’ So it was that when the Scientific American, capitalising on the interest in Conan Doyle’s lecture tours, offered a $2,500 prize to anyone who could produce under test conditions ‘an objective psychic manifestation of physical character’, Houdini was invited to sit on the investigating committee in what was almost certainly intended as a deliberate provocation of Conan Doyle to shift more copy. The other committee members were William McDougall (Professor of psychology, Harvard); Daniel F. Comstock (MIT); Dr. Walter Franklin Prince (Head of the American Society for Psychic Research); Hereward Carrington, psychic investigator; and Malcolm Bird, the assistant editor of the Scientific American. Conan Doyle was not impressed, writing to Houdini:

I see that you are on the Scientific American Committee, but how can it be called an Impartial Committee when you have committed yourself to such statements as that some Spiritualists pass away before they realize how they have been deluded, etc.? You have every possible right to hold such an opinion, but you can’t sit on an Impartial Committee afterwards. It becomes biased at once. What I wanted was five good clear-headed men who would stick to it without any prejudice at all –

Once the Committee got rolling and investigated several mediums without finding anything supernatural about any of them, Doyle dismissed it as a ‘farce’. This was to change with the arrival of ‘Margery’ the medium.

‘Margery’ was the 36-year-old wife of the Boston surgeon Dr LeRoy G. Crandon, Mina. Like Jean Doyle, it had been her husband who first became interested in Spiritualism before Mina discovered her medial abilities. She had given demonstrations before the Nobel Prize winning physiologist-turned-parapsychologist Charles Richet in Paris and performed a séance for the Doyles in London. It was Conan Doyle who recommended the Crandons contact the Scientific American. Mina was a charming and attractive woman, and as a surgeon’s wife she had the social skills to negotiate the attention of Ivy League investigators and the East Coast elite. That the Crandons were rich gave her ‘abilities’ additional credibility, as she clearly did not need the prize money. She often conducted séances naked, allowing herself to be examined to prove she literally had nothing up her sleeve.

Soon after, Malcolm Bird arrived in Boston to conduct a preliminary investigation. Mina duly demonstrated her ability to summon unearthly noises such as ghostly bugle calls and the rattling of chains, and to illuminate the darkened séance room with brilliant flashes of light. She stopped clocks with her mind, made objects float about the room, and apported items as various as dollar bills and live pigeons. Her showstopper was to channel the spirit of her dead brother, Walter Stinson, who had been killed in a railway accident. While in a trance state, Mina spoke in Walter’s voice, and used language that Bird and Crandon felt could never possibly pass the lips of a gentlewoman. Bird was greatly taken with the Crandons and urged the doctor to write to the committee suggesting they set up camp in Boston, which was agreeable as Professors McDougall and Comstock were already based nearby. Bird and Hereward Carrington, in fact, stayed with the Crandons as their guests. Both men were attracted to Mina, and she initiated an affair with Carrington. Bird wrote two pieces for the Scientific American citing Mina’s abilities (using the pseudonym ‘Margery’) in 1923 and 1924, and he now began preparing an article for the July 1924 issue that would strongly imply that ‘Margery’ was likely to qualify for the prize.

Houdini, thus far, had not been involved in the investigations as he was on tour. The first he heard of ‘Margery’ was, like everyone else, from Bird’s reports in the Scientific American, ‘the worse piffle I ever read … fulsome, gushing reports of nothing.’ He rushed to New York to have it out with Bird, who was apparently preparing to certify Mina Crandon as genuine before the full committee had even been convened. To make matters worse, the July issue of the magazine was now in print. Houdini was furious. From what he’d read of ‘Margery’, he was sure his fellow committee members were being duped and was horrified that Bird and Carrington had become so friendly with the Crandons. ‘If you give this award to a medium without the strictest examination,’ he warned Charles Allen Munn, the editor of the Scientific American, ‘every fraudulent medium in the world will take advantage of it.’ Accompanied by Munn, Houdini headed for Boston on a mission of damage limitation, although the other committee members had by then conducted the better part of fifty séances with Mina.

Whereas the Crandons had courted the rest of the committee, who were of the same social class, Houdini was clearly a threat and he believed he had been deliberately excluded from the investigation despite Bird’s protestations. Dr. Crandon was also corresponding with Conan Doyle once a week and had obtained an advance copy of Magician Among the Spirits, cowritten by Houdini and H.P. Lovecraft’s old friend from Weird Tales magazine, C.M. Eddy Jr. In the book, Houdini had liberally quoted his correspondence with Conan Doyle and offered his own account of the Atlantic City séance. No gentleman, they agreed, would ever have made private letters public, ‘entirely disregarding the usual obligations of civilized society.’ Crandon reassured Conan Doyle that he and his wife planned to ‘crucify’ Houdini by conclusively proving ‘the most extraordinary mediumship in modern history.’

‘Margery’ and Houdini

The first séance took place at the Crandon’s home on the evening of July 23. As was the convention, the room was kept in total darkness (as bright lights were anathema to spirits), with the sitters in a circle around a table, all holding hands. Mina was seated in a ‘cabinet’ (dressed on this occasion), a three-sided wooden box introduced into Spiritualist practice by the Davenport Brothers, two famous mediums that had long since been exposed as frauds but whom Conan Doyle still championed. Bird was seated on Mina’s right, her husband on his right; Houdini was on her left. Bird held both Mina and Dr. Crandon’s hands in one of his, so that his other was free ‘for exploring purposes’. In addition to holding her hands, both men’s legs were in contact with Mina’s. In preparation for this, Houdini had worn a tight silk bandage below his right knee all day so that his leg had become swollen and tender, and thus sensitive to any sensation of movement from Mina. Part of Mina’s ‘psychic phenomena’ was the ringing of an electric bell enclosed in a box placed in front of her on the table that was activated by pressure on the lid. ‘Walter’ would use this device to communicate simple ‘yes/no’ answers. As the committee members were sure that in previous experiments they had ‘perfect control’ over her hands and feet, they could not account for the ringing of the bell. Houdini, however, could:

I could distinctly feel her ankle slowly and spasmodically sliding as it pressed against mine while she gained space to raise her foot off the floor and touch the top of the box. To the ordinary sense of touch, the contact would seem the same while this was being done. At times she would say: ‘Just press hard against my ankle so you can see that my ankle is there,’ and as she pressed I could feel her gain another half inch. When she had finally maneuvered her foot around to a point where she could get at the top of the box the bell ringing began and I positively felt the tendons of her leg flex and tighten as she repeatedly touched the ringing apparatus.

Also, holding her left hand, ‘which rested lightly on the palm of my right,’ Houdini was able to feel Mina’s pulse with his index finger: ‘I used the secret system of the “touch and tactics” of the mind or muscle performer (I had given performances or tests in this field of mystery), who is guided by the slightest muscular indication in finding a hidden article. I was able to detect almost every time she made a move.’

Suddenly, ‘Walter’ intervened, asking Bird to leave the circle to get an illuminated plaque to place on the box containing the bell. At Walter’s call for ‘Control!’ Mina placed her right hand in Houdini’s and at that instant her cabinet was thrown violently over. She then placed her right foot on Houdini’s, saying, ‘You now have both hands and both feet.’

Walter, again, took over. ‘The megaphone is in the air,’ ‘he’ declared, ‘have Houdini tell me where to throw it.’ (The megaphone was another popular Spiritualist accoutrement, used for amplifying ghostly voices but also as a prop for object levitation.)

‘Towards me,’ said Houdini, and the megaphone clattered to the floor at his feet. This had happened at other séances and had, wrote Houdini later, ‘converted all sceptics.’

The next afternoon, Houdini took Munn to the séance room and demonstrated how all the tricks had been done. When Bird had broken the circle, Mina had an instant to tilt the cabinet with her hand enough to get her foot under it and topple it over. She then placed the megaphone on her head like a dunce cap. Once she was back under ‘control’ in the circle, she merely nodded her head to drop the megaphone at Houdini’s feet, while a quick snap of her head could have sent it in any direction requested. It was, he said, ‘the “slickest” ruse I have ever detected.’

For the next séance, Munn was on Houdini’s left. Having agreed some simple signs in advance, Houdini was able to break the chain with Munn in secret and to feel around with his left hand. He immediately felt Mina’s head on the table’s edge, tilting it so that the box with the bell fell at her feet. She then did the sliding trick with her leg again, this time snagging her stocking on Houdini’s sock-suspender.

The committee met after the séance and Houdini explained all the tricks that had been baffling them for weeks. They discussed whether to expose her immediately or upon their return to New York. It was agreed that they should wait and continue with the tests, in the hope of discovering more evidence of fraud. None of this was to be communicated to the Crandons. Only Bird disagreed, continuing to argue that Mina was at least fifty per cent genuine. He remained at the house as a guest, and later confessed to Munn that he had told them everything. He also wrote another positive article on ‘Margery’ for the September issue of the magazine, but this time Houdini with W.F. Prince of the ASPR (who doubted Bird’s impartiality), were able to block publication. Houdini insisted that Munn give his word Bird would not write up the exposé. Leaks, however, continued, with syndicated American newspapers running headlines such as: BOSTON MEDIUM BAFFLES EXPERTS; HOUDINI STUMPED; and PSYCHIC POWER OF MARGERY ESTABLISHED BEYOND QUESTION.

The cold war between Houdini and the Crandons and their supporters had now become hot. Houdini was determined to expose Mina; she was equally determined to make the great debunker look like an idiot. He even devoted part of his stage act to demonstrating her ‘tricks’ and published a pamphlet outlining her methods. At the next series of séances in August, Houdini placed Mina in a ‘cabinet’ of his own design that was more like a medieval pillory, with her head poking through a hole in a hinged lid secured with brass straps and her arms sticking out of holes in the side. (Her legs were completely enclosed and effectively immobilised.) Her believers objected owing to the growing belief that Mina was able to move objects using a ‘pseudopod’ similar to that produced by the frequently discredited but nonetheless famous Italian medium Eusapaia Palladino, an eerie, ectoplasmic ‘hand’ that emanated from between her legs.

A colourful performer known for sleeping with her investigators, Eusapia could make valuable objects ‘disappear’, never to be seen again. At a series of experiments in Cambridge headed by Oliver Lodge, she was revealed to be a complete fake, although high profile supporters such as Conan Doyle and the criminologist Cesare Lombroso were convinced of her authenticity. Richet, meanwhile, sat on the fence.

The Crandons noted their disapproval, but consented to the new cabinet, which turned out not to be too much of an impediment when first used as Mina was easily able to break the brass retaining straps with her shoulders. It was, she said, ‘Walter’ who had done this, and also subsequently rung the electric bell. On the next night, Houdini used iron locks.

The next séance maintained the appropriate level of drama by beginning with Bird bursting in and demanding to know why he had been excluded. Houdini called him out for ‘betraying’ the committee and ‘hindering their work.’ Bird protested until it became obvious no one believed him. He resigned from the committee and stormed out. (He also resigned from the Scientific American, becoming a full-time psychic investigator. His first publication in his new field was Margery the Medium.) This time, a folding ruler was found concealed in the new cabinet, with both sides claiming the other had put it there. The séance concluded with ‘Walter screaming, ‘Houdini, you goddamned son of a bitch, get the hell out of here and never come back! If you don’t, I will!’ He also ominously concluded, ‘Remember, Houdini, you won’t live for ever. Some day you’ve got to die.’

Mina was increasingly worried that Houdini was going to denounce her in an upcoming Boston stage show. First, she tried threats. If he exposed her, she said, her friends would get on stage and ‘give you a good beating.’ Houdini replied that her friends would do nothing of the sort. She next tried begging. She evoked her children; she did not want her twelve-year-old son to grow up hearing that his mother was a fraud.

‘Then don’t be a fraud,’ said Houdini.

The Crandons declined any further tests or encounters with Houdini, forcing the committee to make a final decision. In the end, only Carrington voted in favour of Mina’s ‘powers’, and she did not receive the prize, though public opinion remained divided over whether she was or was not the real deal. Carrington was interviewed by the Boston Herald in December, in which he denounced Houdini as a ‘pure publicist’ with ‘no scientific experience in psychic investigation.’ Houdini’s love of the spotlight was similarly used against him by Conan Doyle, who wrote of him:

This enormous vanity was combined with a passion for publicity which knew no bounds, and which must at all costs be gratified … It was this desire to play a constant public part which had a great deal to do with his furious campaign against Spiritualism.

Carrington, like Crandon, was in touch with Conan Doyle, who was happy to take up ‘the conspiracy against the Crandons’ in the press, feeling he had every right to become involved as it had been his lectures on Spiritualism that had inspired the Scientific American prize in the first place. Writing in the Boston Herald, only Bird and Carrington were spared, being described as ‘honest and clear headed.’ Dr. Prince was ruled useless as he was partially deaf and could not therefore properly evaluate ‘direct voice phenomena’, while Professor McDougall was ‘only inclined to credit negative evidence.’ But most of all, he was gunning for Houdini. ‘Were there an advertisement to be gained,’ wrote Conan Doyle, Houdini was ‘a dangerous man,’ continuing:

Various members of this committee had sat many times with the Crandons, and some of them had been completely converted to the psychic explanation, while others, though unable to give any rational explanation of the phenomena, were in different stages of dissent. It would obviously be an enormous feather in Houdini’s cap if he could appear on the scene and at once solve the mystery. What a glorious position to be in! All America was watching, and he could not resist the temptation.

Conan Doyle was, he wrote, ‘amazed’ that a committee consisting of such ‘honourable gentlemen’ should have allowed a man ‘with entirely different standards to make this outrageous attack’ on the ‘reputation of a lady.’ The Crandons, meanwhile, were presented as being of impeccable manners and character:

Finally, this self-sacrificing couple bore with exemplary patience all the irritations arising from the incursions of these fractious and unreasonable people, while even the gross insult which was inflicted upon them by one member of the committee did not prevent them from continuing their sittings. Personally, I think that they erred upon the side of virtue, and that from the moment Houdini uttered the word ‘fraud’ the committee should have been compelled either to disown him or cease their visits.

The implication was more than clear: Houdini was ‘not one of us’, either socially or in his ‘unscientific’ attitude to ‘serious psychical research.’ Rather, he was a publicity-seeking upstart with ideas above his station and a bounder into the bargain. Conan Doyle and Houdini never communicated again, because, ‘I knew,’ wrote the former, ‘by previous experience, that he always published my letters, even the most private of them, and that it would only give him a fresh pretext for ridiculing that which I regard as a sacred cause.’

Conan Doyle invited the Crandons to give some séances in London, making it clear they’d get a much more sympathetic hearing in England. In the end, the Society for Psychical Research sent their investigator, Eric Dingwall, to Boston instead. Like many before him, he was captivated by Mina, and his request that she sit nude while her husband sprinkled her with luminous powder (all in the interests of science, naturally), led McDougall to accuse him of having ‘improper relations’ with Mrs. Crandon, thereby invalidating his investigation. Dingwall initially fell for Mina’s ‘teleplasmic’ hand, until McDougall and a group of Harvard researchers proved to him that it was sculptured animal tissue, also pointing out that the creepy thing only ever appeared when Mina’s husband was sitting next to her in the circle. Conan Doyle, however, continued to vouch for Mina’s authenticity to the bitter end. When the father of modern parapsychology, Joseph Banks Rhine, published his findings that ‘Margery’ was a fraud in the Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology in 1926, Conon Doyle’s response was to write in the Boston Herald that ‘J. B. Rhine is an Ass!’ His last word on the subject came in his article ‘The Riddle of Houdini’, written in 1830, the year of his own death:

Speaking with a full knowledge, I say that this Boston incident was never an exposure of Margery, but it was a very real exposure of Houdini, and is a most serious blot upon his career. To account for the phenomena he was prepared to assert that not only the doctor, but that even members of the committee were in senseless collaboration with the medium. The amazing part of the business was that other members of the committee seemed to have been overawed by the masterful conjurer, and even changed their very capable secretary, Mr. Malcolm Bird, at his behest. Mr. Bird, it may be remarked, with a far better brain than Houdini, and with a record of some fifty séances, had by this time been entirely convinced of the truth of the phenomena.

The final seance 1936

Houdini, meanwhile, remained pragmatic and forthright to the last, telling an interviewer on the Christian Register in 1925: ‘Tell the people that all I am trying to do is to save them from being tricked in their grief and sorrows, and to persuade them to leave Spiritualism alone and take up some genuine religion.’ The following year he died, on Halloween, as a result of a burst appendix. He was 52. Conan Doyle maintained that he had be cursed by ‘Walter’, writing that, ‘He should have taken warning and realized that he was up against powers which were too strong for him, and which might prove dangerous if provoked too far. But the letters he had written and boasts he had made cut off his retreat.’ Houdini’s final (unfinished) project had been a collaborate book with H.P. Lovecraft and C.M. Eddy Jr. provisionally entitled The Cancer of Superstition.

It was Professor McDougall that had the last word at the height of the ‘Margery’ controversy, rather grumpily, as he felt his hand was being forced. (He would have liked the investigation to continue.) Spiritualists had infiltrated the American Society for Psychical Research in support of Mina, forcing Prince to resign and establish a rival group, and Bird was on the verge of publishing his favourable book on Mina. McDougall therefore denounced Mina in the Boston Evening Transcript, at the same time raising the much more interesting question of why she, and indeed her husband, had committed such a protracted and complex fraud? They were already rich; they had no need of the prize money, and had they won it their intention was to donate it to the Spiritualist cause. McDougall’s answer was that ‘Walter’ was a secondary personality that had been the instigator of Mina’s supposed ‘psychic phenomena’, rather like Norman Bates’ mum. Mina was therefore technically innocent of any fraud. ‘If that hypothesis is the correct one,’ wrote McDougall, ‘then the case is one that falls within the field of abnormal psychology rather than in that of supernormal physical phenomena.’ Or perhaps, like many tricksters in the history of Spiritualism – most notably the tragic Fox sisters – she got in too deep playing an initially mischievous game and could not find her way out of it. Or perhaps, like Jean Doyle, she convinced herself that her ‘powers’ were real. Outliving her husband, she continued, at any rate, to perform as a medium until her death in 1941.

None of this, however, explains Dr. Crandon’s part in the drama, as he was undoubtedly colluding with his wife. As Houdini had said of Conan Doyle, it is possible that Crandon was a true believer to the point of delusion. Or perhaps, as the nude séances suggest, there was a sexual dimension to all this. He certainly enjoyed photographing his younger, naked wife while in her ‘trance state’ and sharing the prints with investigators like Bird and Dingwall. Even at the height of their conflict, Conan Doyle and Houdini had both been too polite to ever raise this particular issue.

As Margery continued to give séances, enthusiastically backed by a small army of Spiritualist supporters including Conan Doyle, despite being ultimately debunked by Houdini, the Scientific American, Dingwall and the British Society for Psychical Research, J. B. Rhine of Duke University, and McDougall and his colleagues at the Harvard University Department of Psychology, there was never an obvious winner. Conan Doyle went to his grave convinced of his beliefs, Houdini died a sceptic, Mina a widowed alcoholic. But as the historian Ruth Brandon has convincingly argued, it was really Houdini that triumphed in the long run, as the ‘Margery’ case was the last time ‘psychical phenomena’ were cited as scientific evidence for the paranormal, at least until Uri Geller started bending spoons half-a-century later and the war between credulous scientists and rightly cynical magicians started over, on pretty much the same terms as in 1925. As Houdini always said, ‘Magic is the sole science not accepted by scientists, because they can’t understand it.’

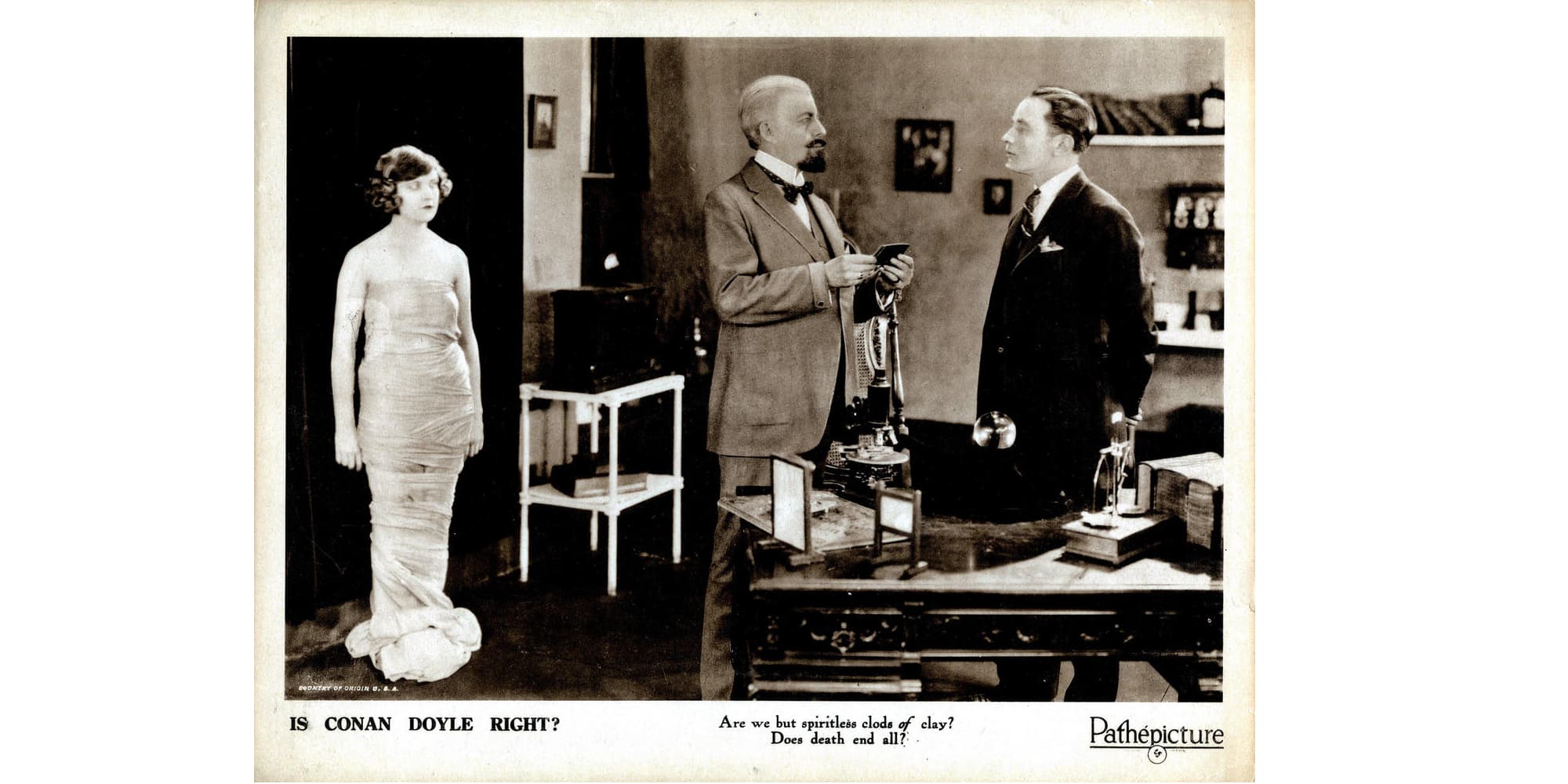

Main image: Lobbycard for the 1923 film ‘Is Conan Doyle Right?’. Credit: Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

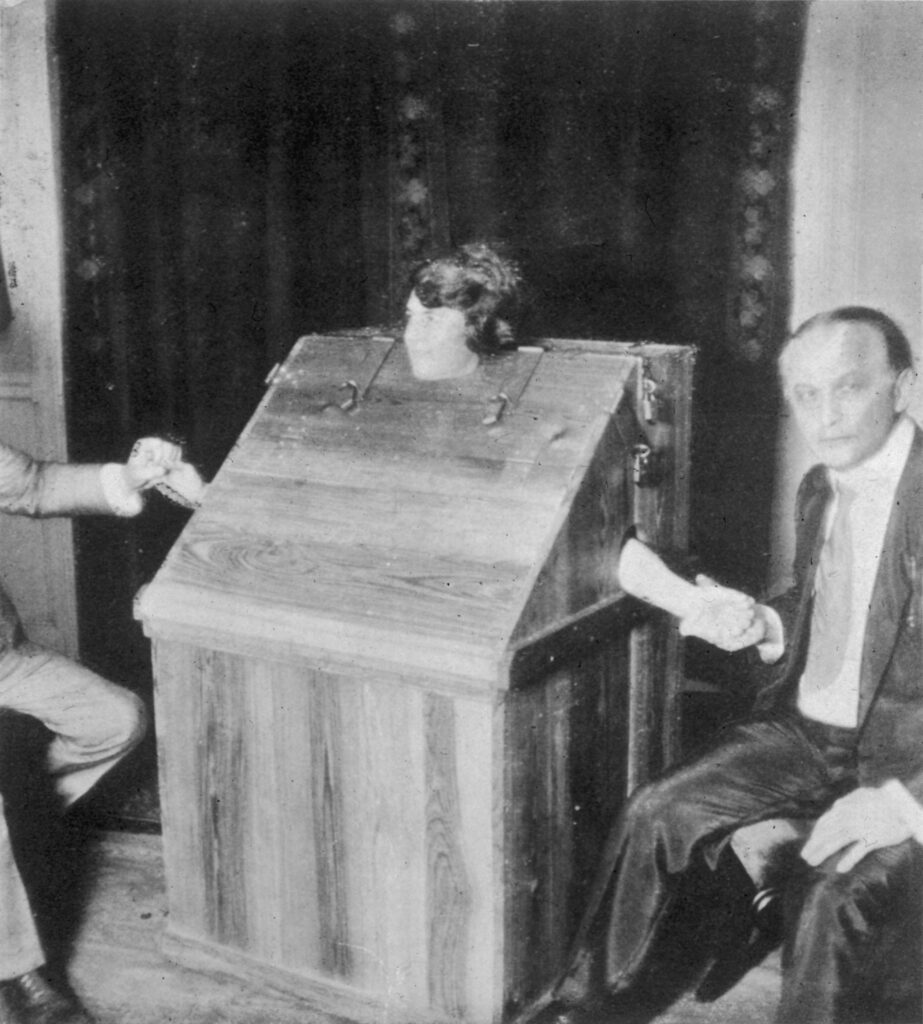

Images above:

1. Houdini and ‘Margery’ (Mina Crandon) in mid-performance. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

2. The final attempt by Houdini’s wife, Bess, to contact him in a seance in 1936. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes & His Last Bow (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Return of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle