Stephen Carver looks at Lady Audley’s Secret

Stephen Carver looks at Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s classic example of Victorian ‘Sensation Fiction’, which helped create the template for modern crime fiction.

When the category of ‘Sensation Fiction’ was first applied as a genre label in the Literary Budget periodical of November 1861, it coined a term for a new species of narrative that was at once innovative, soon-to-be hugely influential, and at the same time the next logical step in a long literary tradition. Much like the opening scene of a bestselling novel, something had happened, was happening, and was going to happen. In publishing terms, the ‘hook’ had been well and truly set, addicting and titillating readers with a chain of withheld secrets and startling revelations. As the name suggests, these books were intended to excite the senses, piling shock after naked shock.

For readers, who were overwhelmingly in favour, and critics, who were not, the concept of the ‘novel of sensation’ coalesced around three English authors. The serialisation of Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White in Dickens’ All The Year Round from 1859 to 1860 (and its subsequent publication as a novel) had quite literally caused a sensation, with readers desperate for the next instalment besieging booksellers. All manner of unlicensed merchandise quickly followed, as well as fashion lines inspired by central characters and even themed tea-rooms. Ellen (‘Mrs. Henry’) Wood’s East Lynne (1861) – a tale of seduction, infidelity, dual identities and murder – was similarly popular and trailblazing, while Mary Elizabeth Braddon, already active in the genre with novels such as Three Times Dead (1860), was shortly to begin her breakthrough serial and masterpiece, Lady Audley’s Secret.

Not that there was anything new about the subject of crime in popular literature, or its use to shock and excite the reader. The early Victorian bestselling triumvirate of Dickens, Bulwer-Lytton and Harrison Ainsworth had all done it in novels such as Oliver Twist, Barnaby Rudge, Paul Clifford, Eugene Aram, Rookwood and Jack Sheppard, with both Lytton and Ainsworth looking back to the Georgian Newgate Calendars, salacious criminal biographies dressed up with a Christian moral. Ainsworth would go on to champion Ellen Wood, and East Lynne was first serialised in his New Monthly Magazine after she failed to find a publisher. In common with his fiction, East Lynne was at heart a melodrama, blending the codes of gothic romance with the domestic realism of George Eliot and Harriette Martineau. And even more extreme examples of ‘criminal romance’ were legion among the penny bloods, most notably those put out by Edward Lloyd and G.W.M. Reynolds in the 1850s. Lloyd, for example, had published The String of Pearls by James Rhymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, in which Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, was loosed upon the world, while Reynolds’ epic serial The Mysteries of London had drawn comparisons between underworld crime lords and corrupt Tory politicians. There were also prototype detective stories to draw upon, like the Mémoires of Eugène François Vidocq – a French criminal turned detective whose work inspired Poe, Hugo and Balzac – Poe’s Auguste Dupin stories and, in England, William Russell’s Recollections of a Detective Police-Officer, and Dickens’ ‘On Duty with Inspector Field’, not to mention the general public’s insatiable hunger for true crime, with murder cases dominating newspaper headlines.

Neither was The Woman in White produced in a vacuum. Collins had been experimenting with crime fiction for the better part of a decade, in novels such as Basil and Hide and Seek. He also contributed a fascinating story, ‘The Diary of Anne Rodway’, to Household Words in 1856, in which a poor seamstress investigates the mysterious death of her best friend. This contained many of the tropes of the sensation novel, such as the amateur detective and a focus on evidence, clues and secrecy. And like his friend, Dickens, Collins loved the stage – as did Braddon – and all three wrote for the theatre and acted. Thus, the energy of popular theatre, the gothic sensibility of the Newgate novel, and lurid crime reporting, with real murders occurring across social classes (not limited to the poor rookeries of popular fiction), poured into conventional middle-class literature, the art form the Victorians never tired of declaring the defining cultural narrative of their age. The real innovation of the sensation novel was that just as it penetrated the domain of the ‘respectable’ novel, its usual setting was the equally respectable bourgeoise home, the bastion of Victorian values. As Henry James, for whom this genre was a guilty pleasure, later wrote, the sensation novel had ‘introduced those most mysterious of mysteries, the mysteries which are at our own doors’. Thus, the gothic became domestic: ‘instead of the terrors of “Udolpho”,’ he continued, ‘we were treated to the terrors of the cheerful country-house and the busy London lodgings. And there is no doubt that these were infinitely the more terrible’.

Alongside The Woman in White, Lady Audley’s Secret represents the pinnacle of sensation fiction. (East Lynne is fun, but it lacks the symbolic or emotional depth of Collins and Braddon.) It is certainly a ‘must read’ for anyone who loves a mystery thriller and is written with such verve that it remains a remarkable easy read despite its vintage. Braddon’s prominent authorial voice makes much use of the first person, which gives the narrative the deceptively anecdotal tone of an old friend relating some particularly juicy local gossip. The novel is also very well paced. Like its gothic antecedents, its structure relies on the twin gears of suspense and escalating shock, and Braddon uses a nice pattern of action followed by reflection leading to further action in tight chapters that are unusually short for the period, giving the text an almost respiratory cycle. Once you tune in, it is difficult to put down, which is exactly how contemporary readers found it.

The beautiful and demure Lady Lucy Audley, née Graham, a young governess and former schoolteacher recently married to the rich widower Sir Michael Audley, has many secrets. Although not the ultimate secret, some of the most significant are so strongly implied in the first of the three ‘volumes’ that comprise the novel that they are hardly ‘secrets’ at all. But around these core transgressions, a vast web of intrigue and menace continues to grow until antagonistic forces inevitably collide and all is revealed, along with one final shock – the beginning, the middle and the twist. Compared at one point in the story with Lucretia Borgia and Catharine de Medici, Lady Audley is complicated. Were we to relate her to The Woman in White, it could be argued that her character combines the beauty and vulnerability of Laura Fairlie with the resourceful intelligence of Marian Halcombe, the treachery of Sir Percival and the malevolent cunning of Count Fosco.

The novel’s protagonist finds himself caught in my lady’s web, beset by dark suspicions and artful misdirection, his loyalties divided between his family and his oldest friend. Robert Audley is Sir Michael’s nephew and, not being blessed with a son, is looked upon by his uncle as his own. Sir Michael’s daughter, the horsey and robust Alicia loves her cousin, who is himself largely unmoved but expects to be browbeaten into marriage eventually. This is because Robert is quite useless, a barrister who does not practice or really do much of anything. He is downright un-English in his disdain for hunting, shooting and riding, and, like his author, is an avid reader of French literature who would happily (paraphrasing Tennyson) ‘lie in the sun and eat lotuses, and fancy it “always afternoon”’. Commensurate to his social class, Robert has a tidy private income and no real need to work and idles away his days reading, smoking, and hanging around the Temple only to socialise with other lawyers: ‘Indolent, handsome, and indifferent, the young barrister took life as altogether too absurd a mistake for any one event in its foolish course to be for a moment considered seriously by a sensible man’. Then something happens that he does take seriously, and he finally applies his legal training to a perplexing mystery. And much as he would prefer to let it go, fearing where his investigations will ultimately lead, he is compelled to go on until his quest for the truth becomes an obsession. As a result of this testing journey, he finally becomes a productive member of Victorian society. The novel is thus a mystery thriller, in which an albeit amateur detective tracks down evidence and leads, and falls for red herrings, slowly uncovering a shocking conspiracy while the subject of his investigations plots to thwart him. Just how far, Braddon teases the reader, will Lady Audley go to keep her secret?

Destined to become ‘The Queen of the Circulating Libraries’, Braddon was only 27 years old when she wrote Lady Audley’s Secret, which makes her technical mastery of plot and form all the more impressive; although this was already her fourth novel and she had certainly learned by doing. In the preceding two years, she had also penned Three Times Dead, The Octoroon, and The Black Band. Before this, she had tried for a career in acting, an unusual move for a middle-class woman, whose unconventional background and family life was an easy target for her critics. She could have been one of her own characters.

Mary was born the third child of Henry and Fanny Braddon of Soho in 1835 (in later life she knocked a few years off). Her father was a failed solicitor who had lied to Fanny about his income and quickly ran the family home into the ground. In her unpublished memoir, Before the Knowledge of Evil (1914), Braddon described a charming, intelligent and well-connected man who might have done well for himself and his young family had he not ‘begun to be his own enemy very early in his career.’ Henry was also a serial womaniser, and when Mary was four, Fanny left him because of his continued infidelity, opting to raise her children alone while remaining, in Mary’s words, ‘primly respectable’. This was a brave move, and Fanny managed to procure her youngest child a decent education, and the gift of a writing desk from her godfather inspired Mary to start writing stories from the age of six. She was also an avid and eclectic reader, devouring Shakespeare, the Romantics, Thackeray and Collins, although her favourite novel of all was Jane Eyre. She grew up determined to support her mother and herself by her own efforts, and went on the stage at 17, under the name of ‘Mary Seyton’ – an interesting mix of the sacred and the phonetically profane – to avoid embarrassing the family. After achieving modest success in the provinces, she attempted to launch her career as a leading lady in London. Reviews were mixed at best, and she went back to rep, now playing older characters, never the lead. Aware that the window was closing, she returned to her first love, writing, in the hope of making a decent living.

While still acting, Braddon had begun to supplement her income by publishing poetry in regional journals. This had attracted the attention of the author and politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton and a shadier paraliterary figure called John Gilby. Both men mentored her as a writer, and she remained a friend and correspondent of Lytton for the rest of his life. Through these connections, she was commissioned to write Three Times Dead by the printer C.R. Empson, who introduced her to the Darwinian workings of Victorian publishing, knowledge she took back to London, resolved to make it a popular novelist. Although her relationship with Lytton was productive, professional, and distant – Lady Audley’s Secret is dedicated to him, ‘In grateful acknowledgement of literary advice most generously given’ – the Svengali-like Gilby wanted more. As he was paying Braddon to write an epic poem, largely to keep her around, the disabled and intense Gilby became increasingly demanding and controlling. When she finally cut the mooring line, he committed suicide. She had by then met a more promising patron.

The Ulsterman John Maxwell was eleven years Braddon’s senior. He had started out selling newspapers in London before going into publishing himself, founding a series of initially short-lived periodicals. Maxwell was already married but his wife, Mary Anne, struggled with mental illness after the birth of their fifth child and had returned to Ireland and the care of her family (some said to an asylum). How could the lover of Jane Eyre resist? Braddon moved in and began serialising Lady Audley’s Secret in Maxwell’s magazine the Robin Goodfellow in July 1861. (Maxwell also republished Three Times Dead under the new title of The Trail of the Serpent.) She abandoned the project when the magazine went bust in September of the same year, beginning work instead on a new novel, Aurora Floyd, another tale of mystery, bigamy and murder with a strong female lead. Lady Audley’s readers, however, were having none of this and demanded the continuation of the serial. It ran again in another Maxwell publication, the Sixpenny Magazine, from January to December 1862, while Braddon was simultaneously writing Aurora Floyd for another of Maxwell’s magazines, Temple Bar, which she also edited. Despite being pregnant (Gerald, the first of the six children they would have together was born in March), she continued to generate text like a steam engine, writing to Lytton that ‘I wrote the third & some part of the second vol of “Lady A.” in less than a fortnight, & had the printer at me all the time.’ She also joked about her magazine work, telling Lytton ‘I have had so much editing work for the last year or two that, when I am in church, I almost want to edit the Liturgy.’

Lady Audley’s Secret was published in three volumes by William Tinsley the same year, beginning his long association with Braddon and her fellow sensation writers ‘Ouida’ (Marie Louise de la Ramée – another Ainsworth discovery), and J. Sheridan Le Fanu. He also went on to publish The Moonstone by Collins. The novel rivalled The Woman in White in its commercial success, running to eight editions by the end of the year. It made Braddon financially independent for the rest of her life (and bailed out Maxwell), and Tinsley finally became a rich man. He built a villa in Barnes with the profits and named it ‘Audley Lodge’. Braddon continued to write two novels a year – some good, some not so much – across several genres, including historical fiction and ghost stories, producing eighty in all, and founding her own magazine, the Belgravia in 1866. She was also an enthusiastic proponent of modern French literature, particularly Zola, Balzac and Flaubert, and produced an English version of Madame Bovary called The Doctor’s Wife. Throughout her long life, she dreamed of writing a truly literary novel, but wrote to Lytton that ‘I am always divided between a noble desire to attain something like excellence – and a very ignoble wish to earn plenty of money.’

The popularity of Lady Audley’s Secret, and its follow-up, Aurora Floyd, also solidified Braddon’s reputation as a scandalous author, writing about the dark and hidden underbelly of middle and upper-class life, and living, it was often hinted, a life as scarlet as those of her heroines. ‘It has, we presume, been her lot to see a phase of life open to few ladies,’ wrote Margaret Oliphant icily in Blackwood’s, adding that she ‘might not be aware how young women of good blood and good training feel.’ W.F. Rae in the North British Review called the novel a ‘monstrosity’, arguing that ‘the notoriety she has acquired is her due reward for having tales which are as fascinating to ill-regulated minds as police reports and divorce cases.’ He concluded that: ‘She may boast of having temporarily succeeded in making the literature of the Kitchen the favourite of the Drawing room.’ The Very Reverend Henry Longueville Mansel made a similar point in the Quarterly Review, writing that novels based on ‘excitement alone’ were necessarily ‘morbid’, and:

indications of widespread corruption, of which they are part of both the effect and the cause; called into existence to supply the cravings of a diseased appetite, and contributing themselves to foster the disease, and to stimulate the want they supply.

Not since the ‘Newgate Controversy’ of 1839 concerning Oliver Twist, Jack Sheppard and the murder of Lord William Russell had the critical establishment been so outraged by the popular novel.

To misdirect the most personal criticism and radiate an air of Victorian propriety, Maxwell placed notices of his marriage to Braddon in the papers in 1864, although no such union could have legally taken place. The ruse was a complete failure. The fiery Irish journalist Richard Brinsley Knowles, then editor of the London Review, was married to Mary Anne Maxwell’s younger sister, Eliza, and made it known to each paper that had published details of Maxwell’s ‘marriage’ that he already had a wife who was very much alive and based in Ireland. Ten years later, Mary Anne Maxwell died, reviving the scandal, which was again stoked by Knowles, causing, among other things, their domestic staff to resign in protest at their ‘living in sin’. Maxwell and Braddon were at last able to marry but felt compelled to move out of the city until the gossip died down.

The couple’s position was notionally similar to that of George Eliot and the critic George Henry Lewes, who had openly lived together since 1854, despite Lewes already being married. That they refused to conceal their relationship – unlike Braddon and Maxwell – gave the moralists even more ammunition, while Eliot and Braddon’s status as independent professional women brought down even more patriarchal ire.

Wilkie Collins, meanwhile, attracted no such attention, although his private life was even more colourful. In 1858, Collins, who disliked the concept of marriage, started living with Caroline Graves, a widowed shopkeeper based near his home in Gloucester Place, and her daughter Harriet, who he thereafter treated as his own child. Caroline had wanted to marry, but Collins did not. She left him while he was working on The Moonstone and married a younger man called Joseph Clow. After two years, she returned to Collins, staying with him at Gloucester Place until his death. Ten years after getting together with Caroline, Collins met the 19-year-old Martha Rudd in Winterton-on-Sea while researching his novel Armadale, and the two became lovers. Like Caroline, she came from a poor background. Martha moved to London and the couple, calling themselves ‘Mr and Mrs Dawson’, had three children together and Collins divided his time between the two families for the remainder of his life. He was also hopelessly addicted to opium, which he had originally taken as an analgesic for gout, and kept decanters of laudanum around the house, which sometimes knocked out guests who mistook the ruby liquid for sherry. But, as Braddon knew as well as Lady Audley, the rules for Victorian men were vastly different to the rules for Victorian women…

This was the era of the ‘separate spheres’ and the ‘angel of the house’. The Matrimonial Causes Act (1857) had reformed the ancient divorce laws, but as the life and work of Braddon’s childhood hero, Charlotte Brontë (and her sisters), demonstrated so tragically and clearly, the options for both working and middle-class women remained limited, however ambitious or educated. And closer to home, of course, were the experiences of Braddon’s mother, which informed her daughter’s scepticism when it came to marriage and reinforced her goal of financial autonomy. In this sense, Braddon and her most famous creation were not so very different. Lady Audley understood gentile poverty just as Fanny and Mary did, and was willing to do anything to escape it. If that meant becoming the trophy wife of a white-haired peer, then so be it. And woe betides anyone that put her hard-won security at risk. As we learn more of her past, can we really judge her for using her good looks and wits to get on in the world? And if her single-minded sense of purpose means people get thrown under the bus along the way, we can at least understand what made her so heartless, so empty. Unlike her husband and his nephew, she does not have the luxury of a private income. In fact, aside from the expensive (and not very portable) gifts her husband bestows upon her, she still doesn’t have any money of her own. Her newfound life of luxury is entirely dependent upon him. This is why she doesn’t take Robert’s many hints to flee to the continent to avoid a scandal. She can’t; not unless she’s willing to go back to square one. Better, perhaps, to stay and fight, especially against such an apparently spineless opponent, and such an easily manipulated husband. She is, in effect, the female equivalent of the self-made men the Victorians loved to celebrate. ‘My ultimate fate in life,’ she admits, ‘depended upon my marriage, and I concluded that if I was indeed prettier than my schoolfellows, I ought to marry better.’ As the academic Elaine Showalter has argued, ‘Braddon’s literary career, like Lady Audley’s marital career, has a clear-sightedness and logic that is modern and chilling’, Braddon admitting to Lytton that she had learned ‘to look at everything in a mercantile sense.’

Braddon is careful not to openly sympathise with Lady Audley, but she nonetheless invites it through the portrayal and development of her character. This is an elegant balancing act, given that she must take Lucy from innocence, beauty and charity to cold-blooded and calculating – as one character observes, ‘not mad, but dangerous.’ Yet Lady Audley is no gothic villain. She’s attractive, sensual, intelligent, resourceful, cultured, and kind; and even as she becomes more desperate, her motivations are obvious. And if this dramatic need is not exactly justified by the author, it is nonetheless understandable. Braddon may not condone her methods, keeping a careful moral distance, but the suggestion is always there for all the female characters – not just Lucy, but her maid, Phoebe, whose husband is an ignorant and proliferate drunk, her step-daughter, Alicia, beset by proposals from upper-class idiots, and the love interest, Clara, living with an arrogant and domineering father – that oppressive, restrictive gender roles and passive domesticity will inevitably lead to frustration, depression and even violence. The metaphor she ultimately chooses is ‘buried alive’. And the message that women need, deserve and are capable of more than a monolithically sexist society allows is artfully expressed at its best when Robert despairs of his seemingly endless and unwinnable contest against his aunt and launches into an internal misogynistic rant:

‘The Eastern potentate who declared that women were at the bottom of all mischief, should have gone a little further and seen why it is so. It is because women are never lazy. They don’t know what it is to be quiet … If they can’t agitate the universe and play at ball with hemispheres, they’ll make mountains of warfare and vexation out of domestic molehills, and social storms in household teacups … To call them the weaker sex is to utter a hideous mockery. They are the stronger sex, the noisier, the more persevering, the most self-assertive sex. They want freedom of opinion, a variety of occupations, do they? Let them have it. Let them be lawyers, doctors, preachers, teachers, soldiers, legislators – anything they like – but let them be quiet – if they can.’

Braddon clearly agrees: ‘Give us freedom of opinion, variety of occupations. Let us be lawyers, doctors, preachers, teachers, soldiers, legislators, anything we like…’ she seems to say, without, of course, actually saying it.

Lady Audley, then, is more anti-hero than a villain. She’s a true femme fatale that male readers can both fear and admire (as does Robert Audley), while most female readers would probably concede that she played the best game she could with the hand she was dealt, with the same kind of subversive self-interest as Defoe’s Moll Flanders or Sade’s Juliette. She may not be a feminist, but she is at least, in the Newgate tradition, a romantic outlaw.

But while the sensation novel took root, dynamically dramatising human drives and social anxieties not normally expressed in Victorian literature, and laying the groundwork for Robert Louis Stevenson, Conan-Doyle, Agatha Christie and the modern murder mystery and police procedural, it would be wrong to conclude that it was as radical a form as its gothic predecessors. Lady Audley’s Secret, like The Woman in White, is ultimately conservative, however exciting. It may show threats to the social order, usually based on gender, race, class and even sexuality, but the genie will always go back in the bottle in the end. Diligent detective work leads to a morally appropriate resolution, reaffirming patriarchal authority and female virtue. As Showalter wrote of the denouement to Lady Audley’s Secret, ‘The spectacle of female ambition, sexual appeal, calculation, social daring and resolve galvanises Robert into becoming a model Victorian hero and head of a household.’ In short, Braddon knew her market. Similarly, in The Woman in White, Walter Hartright marries the frilly Laura Fairlie, not her elder half-sister, Marian Halcomb, who is bold, practical, sexy and clever, but has hair on her upper lip and a disconcerting sense of almost masculine power. Nonetheless, these novels created between them the templates for a genre. The modern crime thriller would be unthinkable without Braddon and Collins.

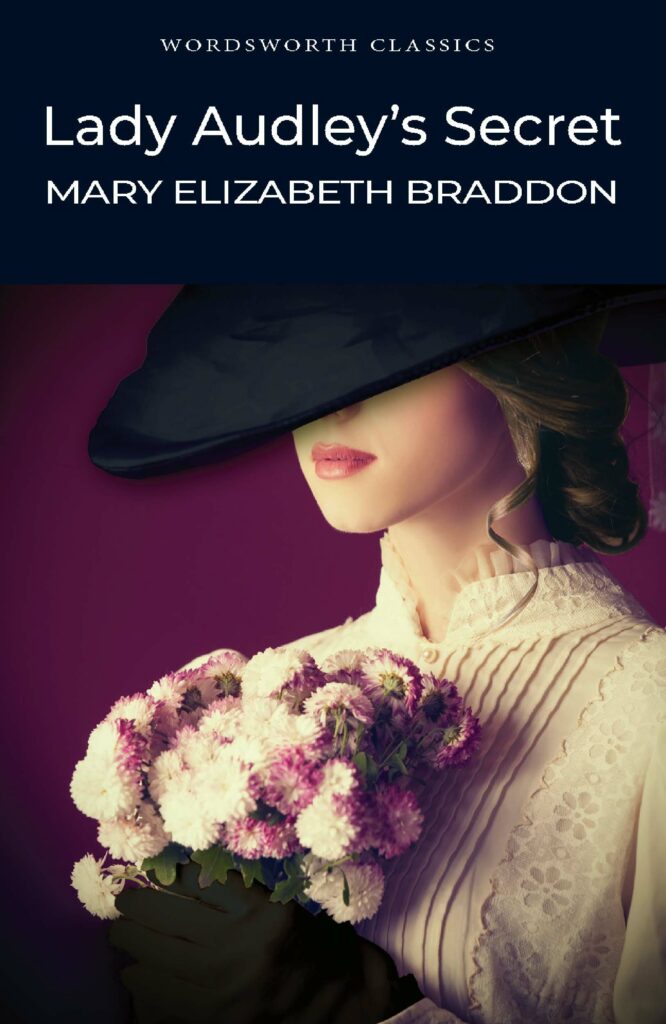

Images: Portrait of Mary Elizabeth Braddon from ‘Punch’ magazine. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo. ‘The Accusation in the Lime Walk’. Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article