Keith Carrabine looks at Little Dorrit

Continuing our ‘Dickensian’ series, Keith Carabine looks at ‘Humbug’ in Little Dorrit

In March 1855 Dickens was inspired to begin Little Dorrit by his rage at the Government’s mismanagement of the Crimean War, the public’s gullibility, and his anguished recognition that we are all ‘miserable humbugs … involved in meshes of aristocratic red tape to our unspeakable confusion, loss, and sorrow’. Little Dorrit is an angry, satirical portrait of a nation in thrall to “an accursed Gentility” and run by the Circumlocution Office composed of a vast family of upper-class twits and scoundrels called the Barnacles, one of whom Frederick happily and proudly chants the informing idea of the novel: “We must have humbug, we all like humbug, we couldn’t get on without humbug. A little humbug and a groove, and everything goes on admirably if you leave it alone” (Book II, chapter 25). The Barnacles are obfuscators who treat all who will not leave them alone, such as Clennam, Doyce, and the Meagles, with “official condescension”, while insisting “that what they had been doing … had been … a sacrifice” (say) for the Meagles’ “ own good” (chapter, 34).

Humbug and obfuscation pervade all institutions in Little Dorrit and are manifest in a wide range of arch self-deceivers who displace their true motives for action through a series of proxies. Thus, Mrs Merdle claims to be “pastoral by nature” but the demands and decorum of “Society” thwart her; Mrs Gowan (a Barnacle) “diligently nurses” the “pretence” that the marriage of her debt-ridden son and consummate hypocrite, Henry, to the rich commoner Pet Meagles is “a most unfortunate business”; and Fanny Dorrit furiously displaces her own anxieties about her prison origins upon her sister, Amy, who is unable to join her in “the game” of Society, so essential to her desire for security and status. Mrs Clennam maintains the fiction “I was but a servant and a minister” and Mr Casby poses as “the patriarch”, but both are “screwers” by “deputy” who transfer the dirty work of the business to Flintwich and Pancks, respectively.

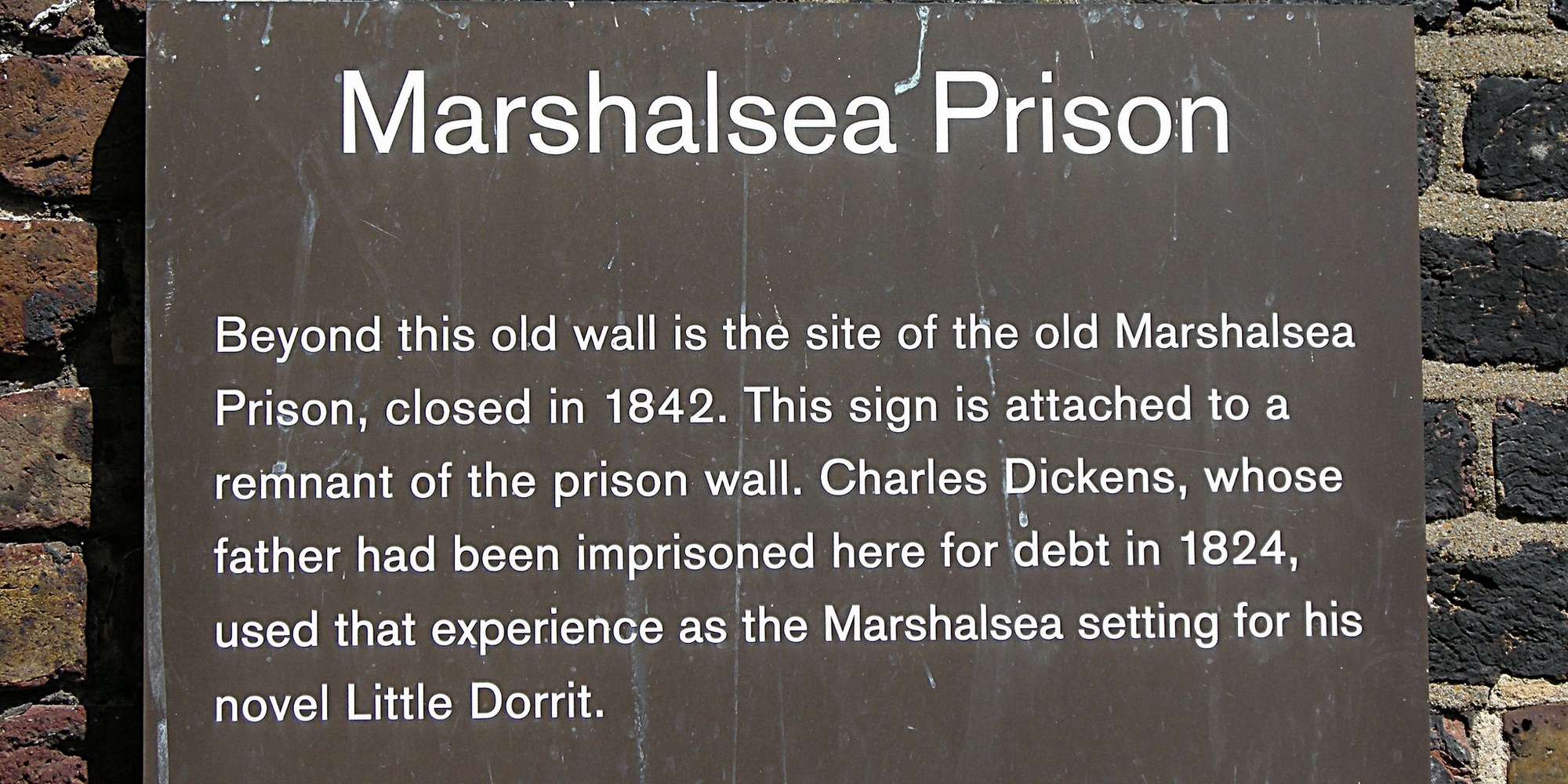

Mr Dorrit, “The Father of the Marshalsea” prison is the purest, most pathetic, and most powerful example of self-deception in the novel. His broken speech interrupted by a series of ‘hems’ and accompanied by a range of brilliant gestures (‘opening and shutting his hands like valves’) superbly registers his excruciating awareness ‘all the time of that touch of shame, that he shrunk before his own knowledge of his meaning’; in this instance that his elaborate circumlocutions are designed to persuade his daughter Amy to suborn herself, by encouraging rather than refusing, the romantic attentions of John Chivery whose courtesies and generosity are so essential to his status and well-being in the Marshalsea (chapter 19). Little Dorrit accepts and recognises that she is her father’s proxy and willingly does the dirty work of earning a living outside, while living in, the jail, and silently enduring the shame that imbues her father’s grotesque humbug re. his gentility and status: and then, after the family are rich she lives with the terrible knowledge that ‘once she leaves her family alone, they pervert everything’. So divorced is Dorrit by the corruptive power of his elaborate fictions from his own natural energies that he cannot even acknowledge the symptoms of his own imminent death, ascribing them by proxy to his brother Frederick: “You are very feeble”, and “Greatly broken”. Dorrit’s death is one of the greatest sequences in English literature, beginning with his demented address to Mrs Merdle’s dinner party welcoming the guests ‘to the Marshalsea’ with the assurance that his request for “testimonials” does not “compromise” him; and then for ten days with his faithful daughter by his side ‘They were in jail again’ and he asks her, as of old, to pawn his watch and sundry trinkets. ‘And he even told her, sometimes, that he was content to have undergone a great deal for her sake’, thereby aptly, if unwittingly, reprising the humbug and guiding principle of the Barnacles and the Circumlocution Office that enables them to avoid responsibility for both their actions and their inevitable, collateral abuse of others. They all inhabit a world in which nobody is to blame in a novel that was originally called “NOBODY’S FAULT’.

Books associated with this article