Stephen Carver looks at M.R. James at Christmas

‘If I’m not very careful, something of this kind may happen to me!’ M.R. James on ‘Writing the Perfect Christmas Ghost Story’

‘There must be something ghostly in the air of Christmas,’ wrote Jerome K. Jerome in the introduction to his darkly comic collection Told After Supper (1891), ‘something about the close, muggy atmosphere that draws up the ghosts, like the dampness of the summer rains brings out the frogs and snails’. Dickens would no doubt agree, as well as anyone who grew up in the 1970s and was scarred for life by the BBC’s annual Ghost Story for Christmas. Further, Jerome continues:

And not only do the ghosts themselves always walk on Christmas Eve, but live people always sit and talk about them on Christmas Eve. Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet around a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories. Nothing satisfies us on Christmas Eve but to hear each other tell authentic anecdotes about spectres. It is a genial, festive season, and we love to muse upon graves, and dead bodies, and murders, and blood (Jerome: 1891, 15–16).

It is often assumed that this is a tradition inaugurated by the publication of A Christmas Carol on December 19, 1843. But Dickens had been channelling something much more ancient, something, in fact, much older than Christmas itself. These are the fireside tales of the Winter Solstice, when our Neolithic ancestors worshipped their death and resurrection gods and the Germanic tribes celebrated Yule, when the wild hunt rose and the Draugr – the ‘again walkers’ – gave up their graves on the darkest day of the year. People have always got together at this time of the year. And as these pagan echoes blend with quasi-Victorian religiosity, like rum and ginger in a winter punch, folk are bound to tell some pretty strange stories. When the unnamed framing narrator of Henry James’ seminal ghost story The Turn of the Screw listens to a friend reading the eerie manuscript, for example, it is on Christmas Eve.

This was doubly so before radio and then television took over, and friends and families still had to entertain themselves. And why stand starchily around an upright piano singing carols when you can scare each other witless? This was the point of Jerome’s book, which both satirised and affirmed the genre of the late-Victorian ghost story, a particular type of English gothic that had become clichéd and ripe for parody by the end of the century. The form was, however, about to be accidently revitalised by Dr. M.R. ‘Monty’ James, a prestigious academic who took a ghoulish delight in frightening the life out of friends, colleagues and students by writing a single ghost story every year and reading it aloud to them in his rooms at King’s on Christmas Eve, extinguishing every candle but one. As he later explained, ‘If any of them succeed in causing their readers to feel pleasantly uncomfortable when walking along a solitary road at nightfall, or sitting over a dying fire in the small hours, my purpose in writing them will have been attained’ (James: 1905, viii).

M.R. James around 1905

Montague Rhodes James Litt. D. (1862–1936), the son of an East Anglian clergyman, was a medieval and biblical scholar. He was a brilliant linguist and palaeographer, and a pillar of the Edwardian Establishment. An old Etonian, James was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge between 1913 and 1915, provost of King’s College (1905–18) and Eton College (1918–36), and Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum from 1893 to 1908. He was awarded the Order of Merit for his services to literature in 1930 and was a Fellow of the British Academy. He disliked Modernism – once describing James Joyce as a ‘charlatan’ – and his world view was Christian and Conservative. He never married. James loved golf, cycling tours of Europe and Eastern England, and, most of all, ghost stories; in particular the work of the Irish writer J.S. Le Fanu, who, he wrote, ‘stands absolutely in the first rank as a writer of ghost stories’ (James: 1923, vii). And despite his prolific research output and impressive academic career, it is his Christmas Eve ghost stories that have assured James’ literary immortality, a twist one imagines his rather dark sense of humour would have appreciated.

As is well known, M.R. James wrote some of the most memorable ghost stories of the twentieth century, which he began to formally publish after his friend and former pupil James McBryde convinced him; chilling tales like ‘Lost Hearts’, ‘Oh, Whistle, And I’ll Come To You, My Lad’, ‘Casting the Runes’, ‘The Mezzotint’, ‘A View From A Hill’ and ‘A Warning To The Curious’. He never wrote in any other fictional form or genre, writing towards the end of his life that ‘I never cared to try any other kind’ (James: 1992, 643). Even today, any ghost story worth its salt must be measured against the yardstick of James’ uncanny tales.

So how do you write the perfect Christmas ghost story? Fortunately, James was quite forthcoming. Despite the crafty disclaimer that ‘I cannot claim to have been guided by any very strict rules’, James knew exactly what he was doing (James: 1911, vi). In an uneven chain of prefaces to his own books, other collections and the odd periodical piece, as a connoisseur of ghost stories James set out a series of guidelines which he refined but never changed in his own work, which I present here in the form of ten creative writing tips in his own words:

Make the setting contemporary…

‘…the setting should be fairly familiar and the majority of the characters and their talk such as you may meet or hear any day. A ghost story of which the scene is laid in the twelfth or thirteenth century may succeed in being romantic or poetical: it will never put the reader into the position of saying to himself, “If I’m not very careful, something of this kind may happen to me!”’ (James: 1911, v).

‘…the belted knight who meets the spectre in the vaulted chamber and has to say ‘By my halidom’, or words to that effect, has little actuality about him. Anything, we feel, might have happened in the fifteenth century’ (James: 1929, 174).

‘…it is almost inevitable that the reader of an antique story should fall into the position of the mere spectator (James: 1927, iv).

…But not too contemporary

‘For the ghost story a slight haze of distance is desirable. “Thirty years ago”, “Not long before the war”, are very proper openings. If a really remote date be chosen, there is more than one way of bringing the reader in contact with it. The finding of documents about it can be made plausible… (James: 1927, iv).

‘…the ghost story is in itself a slightly old-fashioned form; it needs some deliberateness in the telling: we listen to it the more readily if the narrator poses as elderly, or throws back his experience’ (James: 1923, vii).

Slowly develop the supernatural elements

‘…two ingredients most valuable in the concocting of a ghost story are, to me, the atmosphere and the nicely managed crescendo … Let us, then, be introduced to the actors in a placid way; let us see them going about their ordinary business, undisturbed by forebodings, pleased with their surroundings; and into this calm environment let the ominous thing put out its head, unobtrusively at first, and then more insistently, until it holds the stage’ (James: 1927, iv).

‘…our ghost should make himself felt by gradual stirrings diffusing an atmosphere of uneasiness before the final flash or stab of horror … Since the things which the ghost can effectively do are very limited in number, ranging about death and madness and the discovery of secrets, the setting seems to me all-important, since in it there is the greatest opportunity for variety.

‘It is upon this and upon the first glimmer of the appearance of the supernatural that pains must be lavished. But we need not, we should not, use all the colours in the box’ (James, 1931).

Be subtle…

‘Reticence may be an elderly doctrine to preach, yet from the artistic point of view I am sure it is a sound one. Reticence conduces to effect, blatancy ruins it, and there is much blatancy in a lot of recent stories. They drag in sex too, which is a fatal mistake; sex is tiresome enough in the novels; in a ghost story, or as the backbone of a ghost story, I have no patience with it (James: 1929, 172).

‘The ghost story can be supremely excellent in its kind, or it may be deplorable. Like other things, it may err by excess or defect. Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a book with very good ideas in it, but — to be vulgar — the butter is spread far too thick. Excess is the fault here’ (James, 1931).

…But not too subtle

‘At the same time don’t let us be mild and drab. Malevolence and terror, the glare of evil faces, “the stony grin of unearthly malice”, pursuing forms in darkness, and “long-drawn, distant screams”, are all in place, and so is a modicum of blood, shed with deliberation and carefully husbanded’ (James: 1929, 172).

Maintain an air of gothic ambivalence…

‘The reading of many ghost stories has shown me that the greatest successes have been scored by the authors who can make us envisage a definite time and place, and give us plenty of clear-cut and matter-of-fact detail, but who, when the climax is reached, allow us to be just a little in the dark as to the working of their machinery. We do not want to see the bones of their theory about the supernatural’ (James: 1929, 171).

…But don’t break the spell

‘It is not amiss sometimes to leave a loophole for a natural explanation; but, I would say, let the loophole be so narrow as not to be quite practicable’ (James: 1927, iv).

Be scary

‘…the ghost should be malevolent or odious: amiable and helpful apparitions are all very well in fairy tales or in local legends, but I have no use for them in a fictitious ghost story’ (James: 1911, v).

‘…here you have a story written with the sole object of inspiring a pleasing terror in the reader; and as I think, that is the true aim of the ghost story’ (James: 1929, 169).

‘…all writers of ghost stories do desire to make their readers’ flesh creep … On the whole, then, I say you must have horror and also malevolence’ (James, 1931).

Haunted objects are good plot triggers

‘Many common objects may be made the vehicles of retribution, and where retribution is not called for, of malice. Be careful how you handle the packet you pick up in the carriage-drive, particularly if it contains nail-parings and hair. Do not, in any case, bring it into the house. It may not be alone…’ (James: 1992, 646).

Write it well

‘These stories are meant to please and amuse us. If they do so, well; but, if not, let us relegate them to the top shelf and say no more about it’ (James, 1931).

Moving from the theory to the practice, all these elements are already in place in James’ first story, ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook’, which opens Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. (I use this as an example that most readers will know, but not off by heart. If you haven’t read it, skip to the end as there are spoilers ahead.)

James spent most of his life at Eaton and Cambridge, and in terms of his protagonists he stuck to that old creative writing adage ‘write about what you know’. His point of view character, Dennistoun, is therefore ‘a Cambridge man’ who visits the church of St. Betrand de Comminges while holidaying in Toulous to take notes and photographs. Although travelling with friends, he goes to the small town alone. The story is narrated in the first person by another academic who knows him, and is set in 1883, about twenty years before the date of composition, so in living memory but still last century. The church is well-described, in a scholarly kind of way. James knew his gothic architecture. Tension builds slowly. While being shown the church by the sacristan (the verger), the academic is dimly aware that his companion is quite antsy, glancing around nervously, keeping his back to the wall and eager to leave. He also reports that, ‘“Once,” Dennistoun said to me, “I could have sworn I heard a thin metallic voice laughing high up in the tower”’ (James: 1905, 7).

The sacristan mentions an old book he has at home that might interest his companion. This sets Dennistoun’s antennae all of a quiver as he had ‘cherished dreams of finding priceless manuscripts in untrodden corners of France’ (James: 1905, 10). The book is indeed a major find, being a folio collection of pasted-in pages of rare illuminated manuscripts compiled by Alberic de Mauléon, Canon of Comminges from 1680 to 1701. The atmosphere continues to quietly darken, with the sacristan telling his daughter upon arriving home ‘“He was laughing in the church”, ‘words which were answered only by a look of terror from the girl’ (James: 1905, 12).

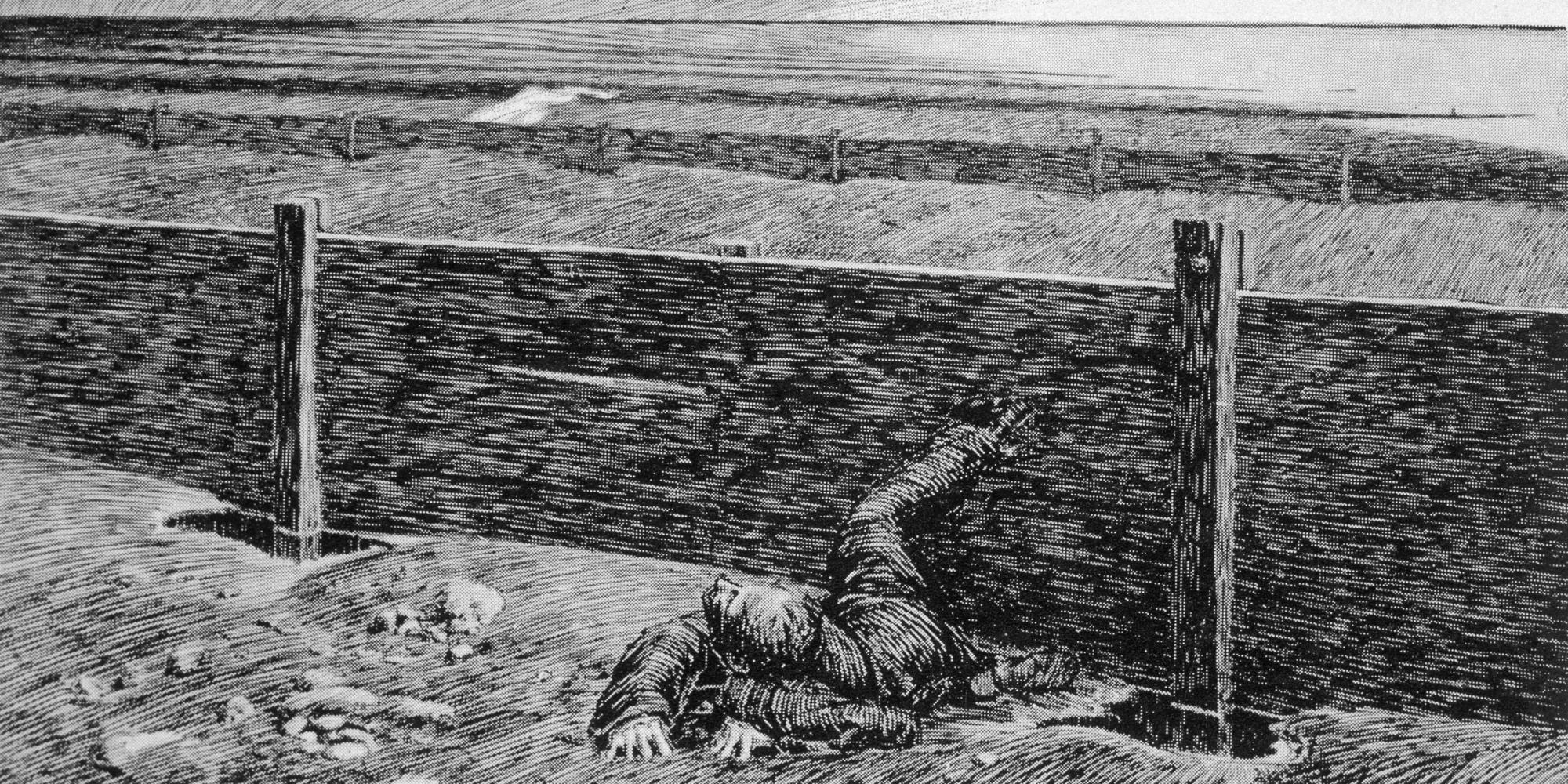

At the back of the book, there is a drawing of a ‘biblical scene’, in which Solomon sits on his throne before five soldiers, one of whom is clearly dead, ‘his neck distorted, and his eyeballs starting from his head’ (James: 1905, 17). The creature that killed him is also present. Before describing it, James describes other viewers’ reaction to it having been shown a photograph back at Cambridge, further establishing the provenance of the tale. This is prefaced by a device that H.P. Lovecraft (an admirer of James) would later take to metaphysical extremes. The narrator begins by telling the reader he can’t really describe the horror of the figure at the heart of scene, and then describes it at length:

I entirely despair of conveying by any words the impression which this figure makes upon anyone who looks at it. I recollect once showing the photograph of the drawing to a lecturer on morphology — a person of, I was going to say, abnormally sane and unimaginative habits of mind. He absolutely refused to be alone for the rest of that evening, and he told me afterwards that for many nights he had not dared to put out his light before going to sleep.

The figure is then presented to the reader:

At first you saw only a mass of coarse, matted black hair; presently it was seen that this covered a body of fearful thinness, almost a skeleton, but with the muscles standing out like wires. The hands were of a dusky pallor, covered, like the body, with long, coarse hairs, and hideously taloned. The eyes, touched in with a burning yellow, had intensely black pupils, and were fixed upon the throned King with a look of beast-like hate.

As James was a an arachnophobe, he then throws in:

Imagine one of the awful bird-catching spiders of South America translated into human form, and endowed with intelligence just less than human, and you will have some faint conception of the terror inspired by the appalling effigy.

The true horror, however, is in his closing line: ‘One remark is universally made by those to whom I have shown the picture: “It was drawn from the life”’ (James: 1905, 18–19).

And when Dennistoun buys the book, for a mere 250 francs, and the sacristan’s daughter forces a silver crucifix on him as he leaves for his hotel, we know that he is going to be seeing the figure from the scrapbook that night, as, by implication, did the unfortunate Canon Alberic…

Dennistoun lives to tell the tale, which James now tells us, although ‘I have never quite understood what was Dennistoun’s view of the events I have narrated’ (James: 1905, 27). The sacristan, however, died shortly thereafter. ‘The book’, he concludes in denouement, ‘is in the Wentworth Collection at Cambridge. The drawing was photographed and then burnt by Dennistoun on the day when he left Comminges on the occasion of his first visit’ (James: 1905, 28).

I shall leave you to apply James’ ‘rules’ to this story.

In the 1970s, Lawrence Gordon Clark traumatised a generation which his annual adaptations of James’ stories for the BBC, which are now available in a BFI boxset which, in my opinion, no home should be without at Christmas. And the tradition continues. This Christmas, there will be an adaptation of James’ story ‘Martin’s Close’ on BBC Four written by Mark Gatiss – who, with his Crooked House series a few years back and other Jamesian dramas established himself as Clark’s obvious successor – and starring Peter Capaldi. I dare you to watch it with only a single candle burning…

Stephen Carver

WORKS CITED

James, M.R. (1905). Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. London: Edward Arnold.

James, M.R. (1911). More Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. London: Edward Arnold.

James, M.R. (1923). ‘Prologue’. In Le Fanu, Joseph Sheridan. Madam Crowl’s Ghost and Other Tales of Mystery. London: G. Bell & Sons.

James, M.R. (1927). ‘Introduction’. In Collins, V.H. (ed). Ghosts and Marvels. Oxford: OUP.

James, M.R. (1929). ‘Some Remarks on Ghost Stories’. The Bookman (December), 169–172.James, M.R. (1931). ‘Ghosts — Treat Them Gently!’ Evening News, 17 April.

James, M.R. (1992). Collected Ghost Stories. London: Wordsworth Editions.

Jerome, Jerome K. (1891). Told After Supper. London: The Leadenhall Press.

Books associated with this article