Mia Forbes takes up the story of Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit

‘This is not the republic I came to see; this is not the republic of my imagination. Charles Dickens’ visit to America in 1842 did not go well, and his disillusionment showed in his next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit. Mia Forbes takes up the story.

“The curse of our house”, said the old man, looking kindly down on her, “has been the love of self; has ever been the love of self.”

This uncharacteristic acknowledgement is made at the end of Charles Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit by the sullen and stubborn old man forced to compete with his namesake nephew for the honour of title character. Although both Martin Chuzzlewits are certainly among the many characters that the reader would readily identify as ‘selfish’, it is perhaps not until this statement that we look back and realise how prolifically “the love of self” has pervaded and perverted almost every relationship and endeavour described over the course of the long novel. Admittedly, this often contributes to the wry humour of the book, with the hopelessly incompetent nurse-cum-mortician, Mrs Gamp, for example, wistfully reflecting on how her patient “would make a lovely corpse”. In literature as in life, however, selfishness is an undeniably destructive force, and indeed it serves to bring the majority of characters to near-ruin until those who shift their gaze from the internal to the external are eventually reprieved.

Best illustrating Dickens’ handling of this theme is his portrayal of mid-nineteenth-century America. The addition of a trip across the Atlantic was the result of poor sales of the early monthly instalments when they first appeared in 1842. Earlier that same year the author himself had visited the States, and his less-than-friendly depiction of the country in Martin Chuzzlewit has been attributed to the disagreements he had had with American publishers over the copyright of his work there. Likewise, the younger Martin Chuzzlewit also fails in his own expedition to America, to which he sets off in order to seek his fortune after a row leaving him estranged from his wealthy uncle.

We get a hint at how Dickens is preparing to present the country while Martin and his naïve but well-meaning sidekick Mark are still aboard The Screw. While preparing to disembark, the only American passenger on board “walked the deck with his nostrils dilated, as already inhaling the air of Freedom which carries death to all tyrants, and can never (under any circumstances worth mentioning) be breathed by slaves.” It probably comes as no surprise to those who associate Dickens with philanthropy and charity, both personal and public, that he would have been just as opposed to slavery as he was to the workhouse. We soon see, however, that it is not only blatant atrocities that are the subject of his scathing satire. From the moment he sets foot in New York, Martin encounters all manner of individual and collective vice concealed beneath a façade of liberty, hard work and resilience.

He arrives the day after a local elections, “and Party Feeling naturally running rather high on such an exciting occasion, the friends of the disappointed candidate had found it necessary to assert the great principles of Purity of Election and Freedom of opinion by breaking a few legs and arms, and furthermore pursuing one obnoxious gentleman through the streets with the design of hitting his nose”.

Dickens’ sarcasm does an excellent job of conveying to the reader the disconcerted feeling experienced by the newly-arrived Martin Chuzzlewit, a feeling that is only to intensify as he meets more and more Americans. Many of these have ludicrously patriotic names, and almost all of them are introduced to him as “one of the most remarkable men in our country”. The phrase is repeated so often that the Englishmen themselves begin to poke fun at it: unlike in many satires, here the author recruits some of his characters to join him in deriding society. Mark soon observes that “they’re so fond of Liberty in this part of the globe, that they buy her and sell her and carry her to market with ’em. They’ve such a passion for Liberty, that they can’t help taking liberties with her”.

Martin, although somewhat irritated by the flamboyant claims of the natives, is nonetheless still “well assured that if intelligence and virtue led, as a matter of course, to the acquisition of dollars, he would speedily become a great capitalist”. Thus encouraged, he spends everything he has on a plot of land in the idyllic-sounding settlement of Eden, planning to set himself up there as a renowned architect. Upon their arrival at Eden, however, it immediately becomes clear that Martin has been conned. Although he had been warned on first setting foot in New York that the American aristocracy was comprised “of intelligence and virtue. And of their necessary consequence in this republic—dollars, sir”, and had himself quickly observed that “all their cares, hopes, joys, affections, virtues, and associations, seemed to be melted down into dollars”, Martin was nonetheless too wrapped up in his own aspirations that he failed to spot in others the very same self-interest at work in his own manoeuvres, and was consequently stripped of every last dollar. Thus Dickens shows us how a solipsistic society in which each person cares only for his own wants and needs is bound to remain dangerous and obstructive despite any pretences otherwise.

Martin, although somewhat irritated by the flamboyant claims of the natives, is nonetheless still “well assured that if intelligence and virtue led, as a matter of course, to the acquisition of dollars, he would speedily become a great capitalist”. Thus encouraged, he spends everything he has on a plot of land in the idyllic-sounding settlement of Eden, planning to set himself up there as a renowned architect. Upon their arrival at Eden, however, it immediately becomes clear that Martin has been conned. Although he had been warned on first setting foot in New York that the American aristocracy was comprised “of intelligence and virtue. And of their necessary consequence in this republic—dollars, sir”, and had himself quickly observed that “all their cares, hopes, joys, affections, virtues, and associations, seemed to be melted down into dollars”, Martin was nonetheless too wrapped up in his own aspirations that he failed to spot in others the very same self-interest at work in his own manoeuvres, and was consequently stripped of every last dollar. Thus Dickens shows us how a solipsistic society in which each person cares only for his own wants and needs is bound to remain dangerous and obstructive despite any pretences otherwise.

Yet even when it becomes clear that the land sale was a scam, Martin and Mark decide to make the best of their situation, emulating what they have been told is true American vigour. In vain, they try setting up shop and engaging with the few other settlers in Eden. Remarking to a local that “The night air ain’t quite wholesome, I suppose?’, Mark receives the blunt reply that “It’s deadly poison”. Despite never claiming to be “one of my most remarkable men in the country”, the local in question, Mr Hannibal Chollop, is an effective representative of the American psyche as portrayed by Dickens. He is extremely proud of the great nation of his birth, and when Martin and Mark, now dwelling in “utter desolation and decay”, reveal that they are not such big fans, he admits that he is “is not surprised to hear you say so. It re-quires An elevation, and A preparation of the intellect. The mind of man must be prepared for Freedom.”

Like his compatriots, Chollop vehemently extols the invariably capitalised values of Freedom, Liberty, Independence and Moral Sensibility upon which America was founded and flourishes, but unlike his more urbane New York counterparts, he is not so adept at holding up the pretence. Taking umbrage at an unspecified but undoubtedly innocent comment of Mark’s, he launches into a tirade that reveals the real limit to the freedoms and opportunities one can expect in the States:

“I have know’d men Lynched for less, and beaten into punkin’-sarse for less, by an enlightened people. We are the intellect and virtue of the airth, the cream Of human natur’, and the flower Of moral force. Our backs is easy ris. We must be cracked-up, or they rises, and we snarls. We shows our teeth, I tell you, fierce. You’d better crack us up, you had!”

This parody of an American prepared to beat detractors “into punkin-sarse” has undeniable comedic value, but the way in which Chollop threatens violence while preaching virtue epitomises the failing that Dickens finds so repellent in the States, even more so than the injustices he sees and criticises in his own land. Whereas “in the Commons House of Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland…it is the custom to use as many words as possible, and express nothing whatever”, the citizens of the United States use as many words as possible to express a lie. Now disillusioned with the nineteenth-century American dream, Martin dares to challenge the sincerity of its principles:

“Are Mr Chollop and the class he represents, an Institution here? Are pistols with revolving barrels, sword-sticks, bowie-knives, and such things, Institutions on which you pride yourselves? Are bloody duels, brutal combats, savage assaults, shooting down and stabbing in the streets, your Institutions! Why, I shall hear next that Dishonour and Fraud are among the Institutions of the great republic!”

And yet such institutions endure. Selfishness ensures self-preservation:

“if I was a painter, and was to paint the American Eagle, how should I do it?… I should want to draw it like a Bat, for its short-sightedness; like a Bantam. for its bragging; like a Magpie, for its honesty; like a Peacock, for its vanity; like an Ostrich, for putting its head in the mud, and thinking nobody sees it …And like a Phoenix, for its power of springing from the ashes of its faults and vices, and soaring up anew into the sky!”

But while the individual may persist and even prosper, the network of relationships he forms around him is weaker and less reliable. Observing this in such vivid colour in America, “Martin – for once in his life, at all events – sacrificed his own will and pleasure to the wishes of another, and consented with a fair grace. So travelling had done him that much good, already.” He is the first of the Chuzzlewit clan to undergo this crucial transformation, pushed to it by his near-death experiences in a society utterly riddled with egoism. In contrast, those who fail to realise the destructive nature of their hereditary “love of self” find that it leads them to ruin.

Apparently, America avoided this pitfall.

In 1868, Dickens returned to New York much changed during the interim decades.

He commented at length on the improvements he saw during a dinner held in his honour (they had apparently resolved the copyright problems), speaking of “how astounded I have been by the amazing changes I have seen around me on every side” and how he had “been received with unsurpassable politeness, delicacy, sweet temper, hospitality, consideration, and with unsurpassable respect for the privacy daily enforced upon me by the nature of my avocation here and the state of my health”. Furthermore, Dickens promised that a copy of the laudatory speech would be appended to every future edition of the two works in which he had criticised the States most fiercely: American Notes and Martin Chuzzlewit.

Whether all those “remarkable men”, becoming aware of their conceit, had dropped the title, embraced humility and learnt to consider the will and wishes of others are doubtful. But moves such as the Emancipation Proclamation, the Homestead Acts that allowed most people to apply for ownership of public land, and the growing influence in New York of Tammany Hall, which advocated for immigrants, constructed orphanages and almshouses, and boosted the city’s social services, must have contributed to Dickens’ refreshed view of America. These examples were all essentially efforts directed externally rather than internally, for the benefit of the other, of the whole as well as the individual. This philosophy of altruism lies at the heart of many of Dickens’ works, and Martin Chuzzlewit is a colourful and compelling study of what happens when a family or society tries to function without it.

Further reading about the Life and Works of Charles Dickens: The Dickens Society

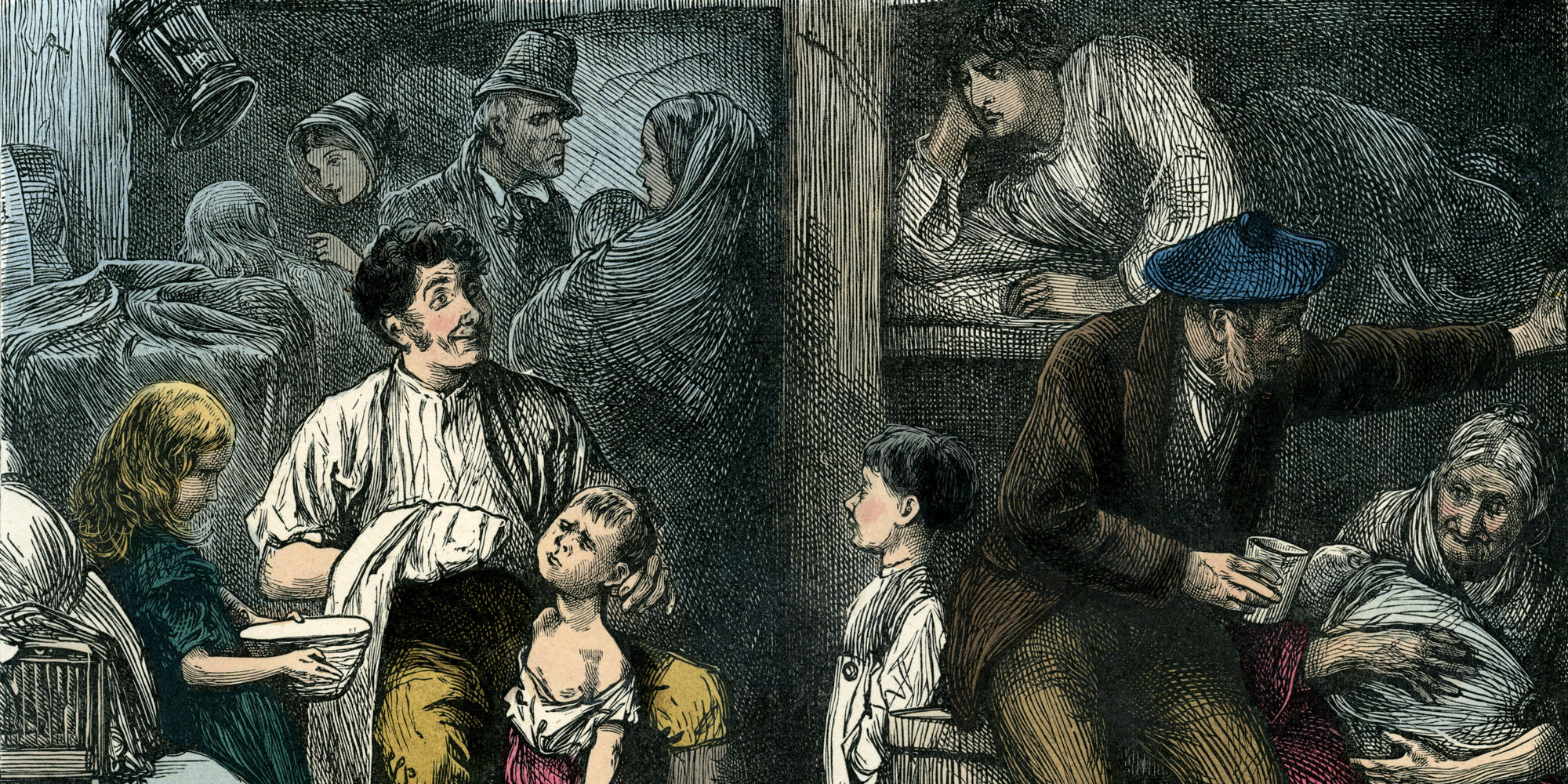

Main Image: Mark Tapley and other passengers on board The Screw, bound for America. Illustration by Fred Barnard (16 May 1846 – 28 September 1896)

Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Image above: Charles Dickens while on his second visit America in 1867-1868. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article