Sally Minogue looks at Mansfield Park

In the third blog in her short series on Empire, Sally Minogue considers whether the hidden issues of slavery in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park have an impact on the moral compass of the novel.

At the heart of any discussion about Empire and the literature of the past is the question of historicity. Is belonging to a prior historical moment sufficient to exonerate a writer who is complicit with the common attitudes of the time, which we might now condemn? Or do we have a duty as readers of literature to continually re-examine texts from the point of view of a 21st century understanding? Edward Said, who wrote the ur-text on such matters, Culture and Imperialism (1993), insists that we should re-examine texts, and suggests the ways in which we should do it. Said argues:

Western writers until the middle of the twentieth century … wrote with an exclusively Western audience in mind, even when they wrote of characters, places, or situations that referred to, made use of, overseas territories held by Europeans. … We now know that these non-European peoples did not accept with indifference the authority projected over them … We must therefore read the great canonical texts with an effort to draw out, extend, give emphasis and voice to what is silent or marginally present or ideologically represented … in such works. (Culture and Imperialism, 78)

Said calls this ‘contrapuntal reading’ (78), and it is the approach I bring here to Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (which also forms one of his case studies). Just to clarify for anyone unfamiliar with the plot, characters I mention include Sir Thomas Bertram, the paterfamilias of his English estate, Mansfield Park, his sons Tom and Edmund, and Fanny Price, his wife’s niece, who is taken into their family from the age of nine. For the main action of the book post-childhood, Fanny is a young woman of eighteen.

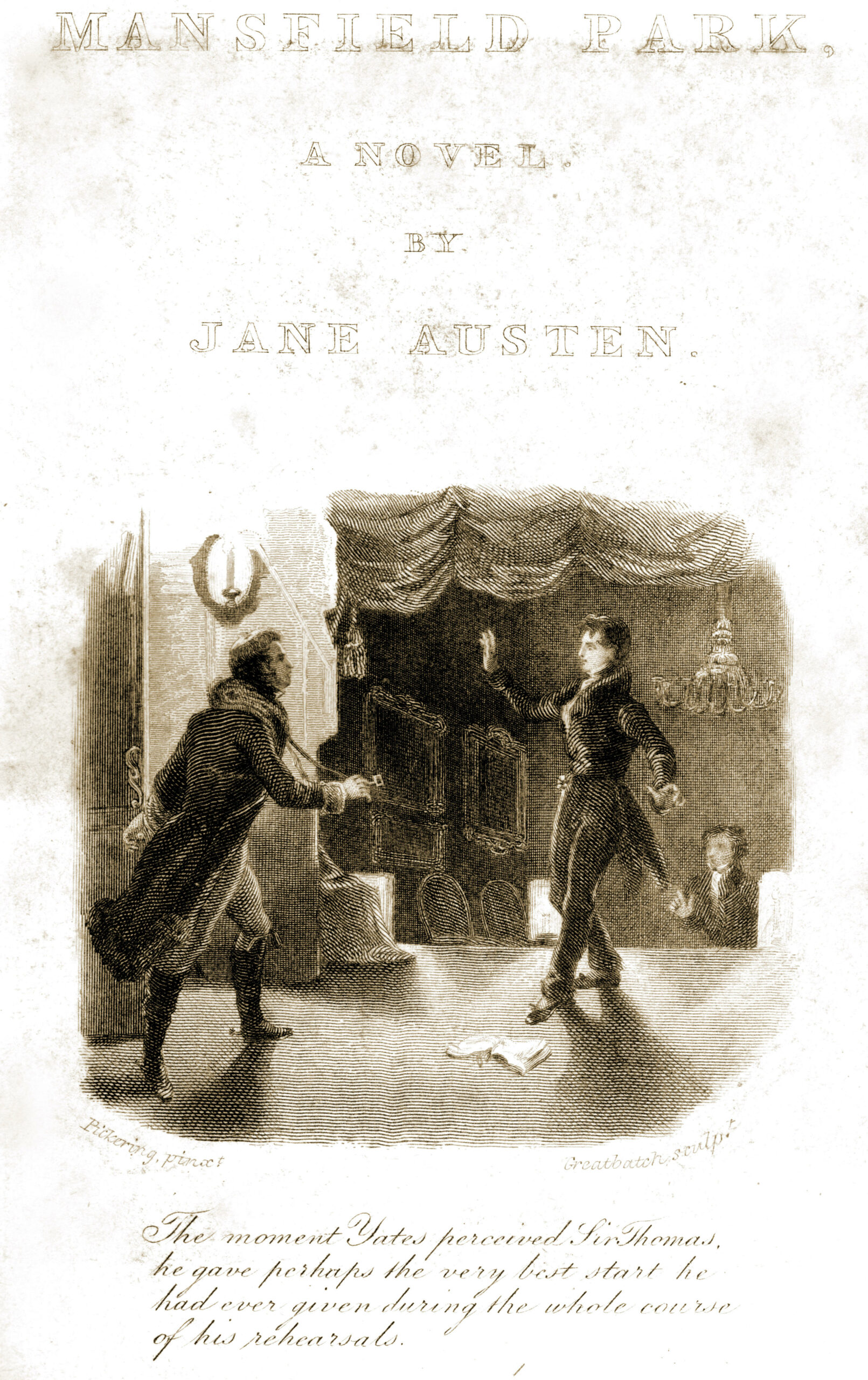

Mansfield Park frontispiece

‘What is silent or marginally present or ideologically represented’ in Mansfield Park is Sir Thomas Bertram’s economic interest in Antigua. On the few occasions that it is mentioned, a space opens up in the novel behind the name ‘Antigua’ and from a 21st century position we can and should fill it with the words unsaid. Antigua came under British rule as early as 1632. Its first sugar plantation was established in 1674, and from then on sugar was the main crop, exploited by British landowners – of whom Sir Thomas Bertram, in the early 1800s of the novel, is one. His estates there are not flourishing, however, which necessitates his presence there to manage them in person for, eventually, two years, an absence which is crucial to the narrative development of the novel. Not mentioned at this early stage of the novel is the fact that the sugar plantations of Antigua were dependent on slave labour and so on the slave trade. Only four years after the founding of its first sugar plantation, half of Antigua’s population was made up of African slaves, and by the 1770s the slave population had peaked at 37,500, and the native Carib population was in corresponding steep decline. Thus when Sir Thomas had established (or inherited) his estates, probably around the same time as his marriage, 20 years before the action of the novel begins (1), the slave trade to Antigua was at its peak. At about the same time, anti-slavery movements began to develop in Britain, with the slave trade finally prohibited in the British Empire by Act of Parliament in 1807, so the current action of the novel occupies a space historically in which public conversations about slavery were well established.[1] With sugar at the centre of the West Indian trade, a comestible present on every tea table, the anti-slavery movement encouraged a boycott of sugar and women in particular joined local anti-slavery committees. My somewhat obvious point here is that Jane Austen would have known all about the slave trade, its role in the production of sugar, and the arguments for and against it in public British discourse, as well as its centrality to the economic health of a family such as the Bertrams, when she chose to make Antigua the place where Sir Thomas’s estates were held.[2]

Yet the only specific reference she makes in the novel to all that underlies the name Antigua is itself a lacuna, a thing unspoken. Edmund is discussing the quieter, perhaps less entertaining, social atmosphere brought about by his father’s return from his West Indian estates, whereupon Fanny avers ‘“The evenings do not appear long to me. I love to hear my uncle talk of the West Indies”’. Nonetheless, Edmund notes, she is ‘one of those who are too silent in the evening circle’:

“But I do talk to him more than I am used. I am sure I do. Did you not hear me ask him about the slave trade last night?”

“I did – and I was in hopes the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of it farther.”

“And I longed to do it – but there was such a dead silence!” (157)

It is a silence that reverberates in the novel – and is characteristically reported here only at second hand, so that as readers we are at one remove from it.

It might be argued that the narrative silence is there because the matters concerning Antigua have no purchase on the central material of the novel. But of course they do, even if that is unstated. The wealth and security of Mansfield Park depends on the generation of wealth in Antigua – hence Sir Thomas’s long absence to ensure that all thrives properly there. Again, there is a notable silence on how that return to prosperity has been managed. The unnamed central prop of his prosperity is the slave trade itself, now under threat from abolitionists. No surprise that there is such ‘a dead silence’ when Fanny mentions it. Similarly her naïve enjoyment of hearing Sir Thomas talk of the West Indies occludes any reference to how slaves live there and what they endure. The lack of interest shown by her cousins in the subject does speak to Sir Thomas’s later understanding that he has not educated his children well. They are the unthinking recipients of the social and financial security of those born into wealth and position. Fanny is not, being aware as she is of the minute niceties of difference in her own place in the household (the not having a fire lit for her being only the most obvious). Her engagement with Sir Thomas’s estates does not, of course, mean that she is engaged with the moral questions arising from the slave trade, though one longs to hear the discussion that Austen might have written. But that imaginative enterprise is firmly, authorially, closed down.

More significant in terms of how we judge the novel is the way in which Austen invests a particular sort of moral value in the eponymous Mansfield Park. The shenanigans of the play, which can only take place because of Sir Thomas’s absence, remind us of the deep distance between the young people’s playing at immorality, and the far darker immorality of the economics which make that theatrical space available to them. The moral narrative of the novel is that Sir Thomas returns and puts things right by disbanding the theatricals. Having restored the financial prosperity that is the foundation of both his aristocratic position and his property, and on which so many of those who figure in the novel depend, he can indulge some reflections on his own shortcomings and put his own house in order. His final acceptance of Fanny as true member of his family puts her at the centre of the novel’s moral compass. Order is restored and all’s right with the world. But for the small matter of the whole thing’s depending on the horrors of slavery. Those horrors disappear not just into the margins of the novel but into the empty space reverberating behind that immense silence.

In the same way as slaves are reduced to the silent ghosts of the novel, the traces of slave society in Antigua have been extremely difficult to reclaim, because their living places were generally made of organic materials, wattle and daub, unlike the stones of the plantation owners’ houses. Similarly, written relics are few since slaves were kept uneducated, and though there are both famous and lesser known slave narratives, the records of day to day life for a slave in Antigua, even if written down, are likely to have perished. A recently published survey of Antigua’s slave history, An Archaeology and History of a Caribbean Sugar Plantation on Antigua, ed. Georgia L. Fox, investigates a specific, large plantation, Betty’s Hope, using archaeological and anthropological approaches. Fox reveals just how difficult it has been to document and provide material evidence of the life of slaves, whilst there is detailed evidence available of the economic organisation of the plantations, and of the material nature of ‘the Great House’, the home of the plantation owner.

Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott’s poem, ‘Ruins of a Great House’ (1953-4), investigates just such contradictions, as he wanders, in the assumed narrative of the poem, in the ruins of such a house, in a lime plantation. Limes were used to combat scurvy aboard the ships that plied the slave trade – not, of course, for the slaves themselves, but for those who sailed the ships. In a poem bursting with English poetic reference, Walcott (only 23 at the time of writing it) offers a coruscating attack on colonial ‘plantation’, yet at the same time he almost unwillingly surrenders to a compassion which can include the worst horrors of slavery in a human embrace, drawing on John Donne’s sermon, ‘No Man is an Island’. The irony is not lost on Walcott that if he follows Donne’s injunction, it means including the brutal slave owners in his compassion; but for those owners, slaves were not included in humanity. Much of the poem is fiercely angry:

A spade below dead leaves will ring the bone

Of some dead animal or human thing

Fallen from evil days, from evil times

And later

Ablaze with rage, I thought,

Some slave is rotting in this manorial lake

Bones and drowned bodies, akin to the bone and body of the poet (hailing from the island of St Lucia), who now speaks for those who could not speak, or left no trace.

A deeper current of the poem speaks of the rottenness of Empire, inextricably woven in Walcott’s mind with poetry:

… I thought next

Of men like Hawkins, Walter Raleigh, Drake,

Ancestral murderers and poets, more perplexed

In memory now by every ulcerous crime.

The world’s green age then was rotting lime

Whose stench became the charnel galleon’s text.

The rot remains with us, the men are gone.

The rot remains with us. ‘The charnel galleon’s text’ is a reference to the slave ships, drawings of which were distributed and published in Austen’s time to show the vile conditions those seized for slavery were subject to, even before they reached the plantations on which they would work in inhumane conditions.

What Walcott struggles with in this poem is the fact that people just like him would have been treated as non-human by the plantation owners whose grounds he here wanders. By a historical chance he has escaped that fate. He can be a poet, like Raleigh before him; he can investigate the complexities of compassion, like Donne; he can even feel compassion, if reluctantly, for those who inflicted the suffering. But the power, the fury of the poem is for those to whom no compassion was extended.

It may seem a long stride from Walcott to Austen. But in fact it is not. He counterposes images of long-dead slaves on a plantation just such as Sir Thomas Bertram derives his wealth from, with himself as an imaginative writer. In so doing he closes up that gap in time and allows us to understand that the slaves on Austen’s Antiguan plantation were no different from him. Austen, in calling up Antigua but remaining deliberately silent on it, leaves us as readers to fill in the gaps. At the same time she actively espouses Mansfield Park as the repository of moral value by the end of the novel. But beneath its aristocratic stones and its wide spaces lie other stones and spaces, those of the plantation’s great house and the now obliterated dwellings, and utterances, of slaves. If we remember this, the moral power of Mansfield Park is hollow, and likewise that of the novel itself.

Said doesn’t deny that Mansfield Park is an impressive and important novel. Like Chinua Achebe reacting to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, like Inua Ellams struggling with Kipling’s racist representations, like Walcott himself, recognising the eloquence of English poetry and prose arising from a society which has a rottenness at its core – he is remarkably magnanimous in his approach. We are not asked not to read these works. But we are asked to read them with a full awareness of ‘what is silent or marginally present or ideologically represented’. These commentators remind us of an important truth: people just like them and us were, in one way or another in these works of literature, treated as sub-human or erased from the text and so silenced altogether. It is our responsibility as readers to fill in those silences.

I am indebted to a Twitter friend, Peter Leyland (@PeterLeyland12) for mentioning to me the 1999 film of Mansfield Park, directed by Patricia Rozema. I have not seen the film, so can’t comment on its quality, but internet accounts and some academic articles make clear that it includes direct references to slave ships and slave plantations, and deliberately fills the silences I have discussed above. This was Rozema’s specific intention, and one of the devices she uses is the discovery by Fanny of drawings Tom had made on his trip to Antigua, shocking images of physical and sexual violence wrought on slaves.

Page references in brackets are to the Wordsworth edition of Mansfield Park. Wordsworth publishes all of Austen’s novels.

Georgia L. Fox (ed.), An Archaeology and History of a Caribbean Sugar Plantation on Antigua, University of Florida Press, Florida, 2020

Edward W Said, Culture and Imperialism, Chatto and Windus, London, 1993

Claire Tomalin, Jane Austen: A Life, Penguin Books, London, 1998

Derek Walcott, Collected Poems 1948-1984, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1987

[1] This did not put an immediate end to slavery itself; that was abolished in most British colonies by Act of Parliament in 1833.

[2] Claire Tomalin, in Jane Austen: A Life, 289, notes the Austen family’s link with the slave trade – in 1760 Austen’s father had taken on the role of trustee of a plantation in Antigua belonging to an Oxford contemporary, James Nibbs, who later became Jane’s godfather. Tomalin argues however that references in Emma and other circumstantial evidence suggest that Austen herself was on the abolitionist side of the argument.

A BBC News article about unearthing the archaeology of the slave system in Antigua can be found here: Unearthing Antigua’s slave past – BBC News

Main image: Godmersham Park, owned by Austen’s brother Edward (inherited from the Knights who ‘adopted’ him, so Fanny’s story is imitative of that). Austen visited there many times and it’s generally thought that she based the Mansfield Park house and estate on it. Credit: Universal Art Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Above: Illustrated frontispiece to an edition of Mansfield Park which is a reference to and quote from the point when Sir Thomas interrupts the theatricals – which I discuss in the blog.

Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Above: Derek Walcott, winner of the 1992 Nobel Prize of Literature. Credit: TT News Agency / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

Mansfield Park (Collector’s Edition)

Jane Austen