Lights, Camera, Sherlock: Part One

The history of the media career of Sherlock Holmes, the world’s most famous detective in four parts, by David Stuart Davies.

PART ONE: EARLY DAYS

As a young boy, Arthur Conan Doyle loved his trips to the theatre and in later life, he wrote several pieces for the stage. It is no surprise then that many of the characters he created for his works of fiction such as Sir Nigel, Brigadier Gerard and Professor Challenger are tinged with rich theatricality. And none more so that his most famous character, Sherlock Holmes. While Doyle grew tired of his character and killed him off by hurling him into the Reichenbach Falls, Holmes began developing an independent career beyond the printed page.

The first actor to portray the Great Detective in public was Charles Brookfield in a bit of comic nonsense called Under the Clock at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1893. The piece made great fun of Holmes and his fawning companion, Watson. In 1894 Richard Morton and H. C. Barry penned a popular song, The Ghost of Sherlock Holmes which did the rounds of the music halls. Both these ventures reveal how famous Holmes had already become so early in his career.

The American actor William Gillette obtained permission from Doyle to turn his hero into a stage star. Gillette took the bare bones of a script Doyle had started but lost interest in and wrote the play, Sherlock Holmes. The plot of the play, which opened in New York in 1899, was largely drawn from the Holmes stories ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ and ‘The Final Problem’. It came to London in 1901 and ran for six months playing to capacity houses at the Lyceum Theatre. The close association between character and actor became legendary. At a revival of the play at the Duke of York’s theatre in 1905, a young Charles Chaplin essayed the role of Billy the page. Gillette appeared in a screen adaptation of the play in 1916. The movie was feared lost for almost a century until a print was discovered in the vaults at the Cinémathèque Française, the French film archive in 2014. The play was successfully revived by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1974 with John Wood in the lead.

It was in 1903 that Sherlock Holmes made his first screen appearance in a one-minute comedy made by the American Mutoscope and Bioscope Company. Sherlock Holmes Baffled is little more than an exercise in primitive trick photography with the villain mysteriously disappearing and reappearing in the Baker Street rooms to confuse the sleuth.

Holmes’ second screen exploit in 1905 also originated from an American studio, Vitagraph, and bore two titles: Held for Ransom and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Lasting eight minutes, it claimed to have been based on The Sign of the Four. It also gave us the first screen Holmes who can be positively identified: Maurice Costello.

During the early part of the twentieth century, there were a confusing number of short Sherlock Holmes films. Perhaps the most unusual was A Black Sherlock Holmes, a two-reeler with a cast of black actors featuring Sam Robinson. While Sherlock Holmes was ignored by his own country’s infant film industry, moviemakers in Europe embraced the character wholeheartedly. In 1912 Conan Doyle sold the film rights to the French film company Éclair, although he did not involve himself personally in the productions. The features were filmed in Britain in 1912 with a British cast with the exception of the French actor Georges Treville who played Holmes.

The first full-length British Holmes feature, A Study in Scarlet, appeared in 1914 produced by Samuelson Film Mfg. Co. Ltd. and was quite an epic for these early days, lasting one hundred and eight minutes. The movie followed Doyle’s plot very closely. The sleuth was played by James Bragington, who was not an actor but merely a studio employee who resembled the accepted image of Holmes. The scenes set in the Utah desert were filmed on the sands of the Southport, the English seaside resort.

Examining the large output of silent Holmes movies, one can see that they fell into one of two camps: either they attempted, with varying degrees of success, to be true to the character and the plots of the stories; or they just took the basic elements of Holmes and set him in completely new and sometimes inappropriate scenarios, ignoring most of the original traits and trappings of the character. Already Sherlock Holmes was becoming the puppet of the filmmakers. Between 1910 and 1920 over fifty silent Holmes movies were made.

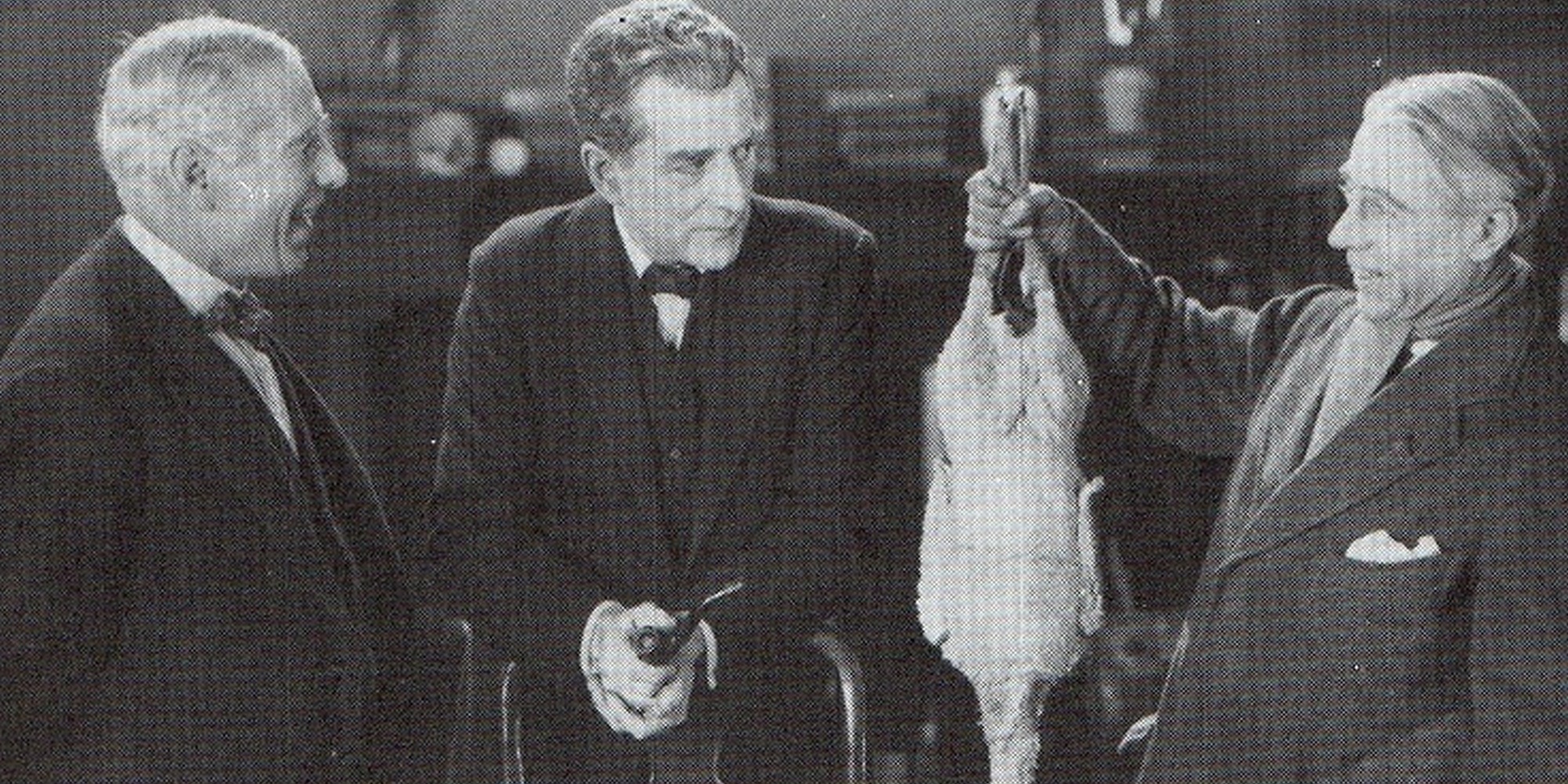

In 1922, John Barrymore, ‘the great profile’, donned the deerstalker for the Goldwyn Pictures production of Sherlock Holmes. Barrymore gave us a matinee idol Holmes: a youthful, handsome tousled-haired fellow rather than the middle-aged figure as he had been presented in other movies. However, his nemesis Professor Moriarty was played as a grotesque figure in the Grand Guignol fashion by German Actor Gustav von Seyffertitz. So eerie and powerful was his performance that when the film was first released in Britain the title was changed to Moriarty.

There can be no doubt that Eille Norwood was the silent movies’ greatest Holmes, if only by the sheer volume of his output: he starred in forty-seven titles in two years for the Stoll film company. He was also a consummate player and while not possessing the Paget-like gaunt, aquiline features, he was convinced in all other departments despite being sixty when he first played the role. Norwood took the challenge of playing Holmes very seriously, absorbing the various details of Holmes’ mannerisms and dress. He even shaved his hairline to create the impression of extra ‘frontal development’. His piece de resistance was his remarkable facility for disguise. He once turned up at the studio in one of his Holmes disguises and the doorman refused him entry because he did not recognise the actor.

Norwood made three series of two-reelers along with a feature version of The Hound of the Baskervilles (1922). Unfortunately, because of the fidelity to the originals and director Maurice Elvey’s unimaginative direction, these films tend to have too much ‘dialogue’ which slows down the pace of the narrative. Nevertheless, there was one real touch of showmanship in The Hound: the creature itself was hand-painted to create a luminous glow ensuring that its infrequent appearances do carry a token shock value.

Norwood himself was considered to be a splendid incarnation of Holmes. In fact, many reviewers referred to his portrayal as ‘an impersonation.’ The Moving Picture News stated that ‘Norwood is Holmes in countenance, personality and conduct.’ Conan Doyle also was among the admirers and presented the actor with the jazzy dressing gown which he wore in most of the movies. There was a final feature, The Sign of Four, in which Norwood’s rather ancient Watson, Hubert Willis, was replaced by the younger Arthur Cullin to allow him to be romantically involved with Holmes’ young female client, Mary Morstan.

Pictured: John Barrymore as the Great Detective