The Invisible Man: The Hands Can’t Hit What the Eyes Can’t See

In the second part of his look at the film adaptations of ‘The Invisible Man’, Parker Lancaster reviews the sequels that followed James Whale’s classic adaptation.

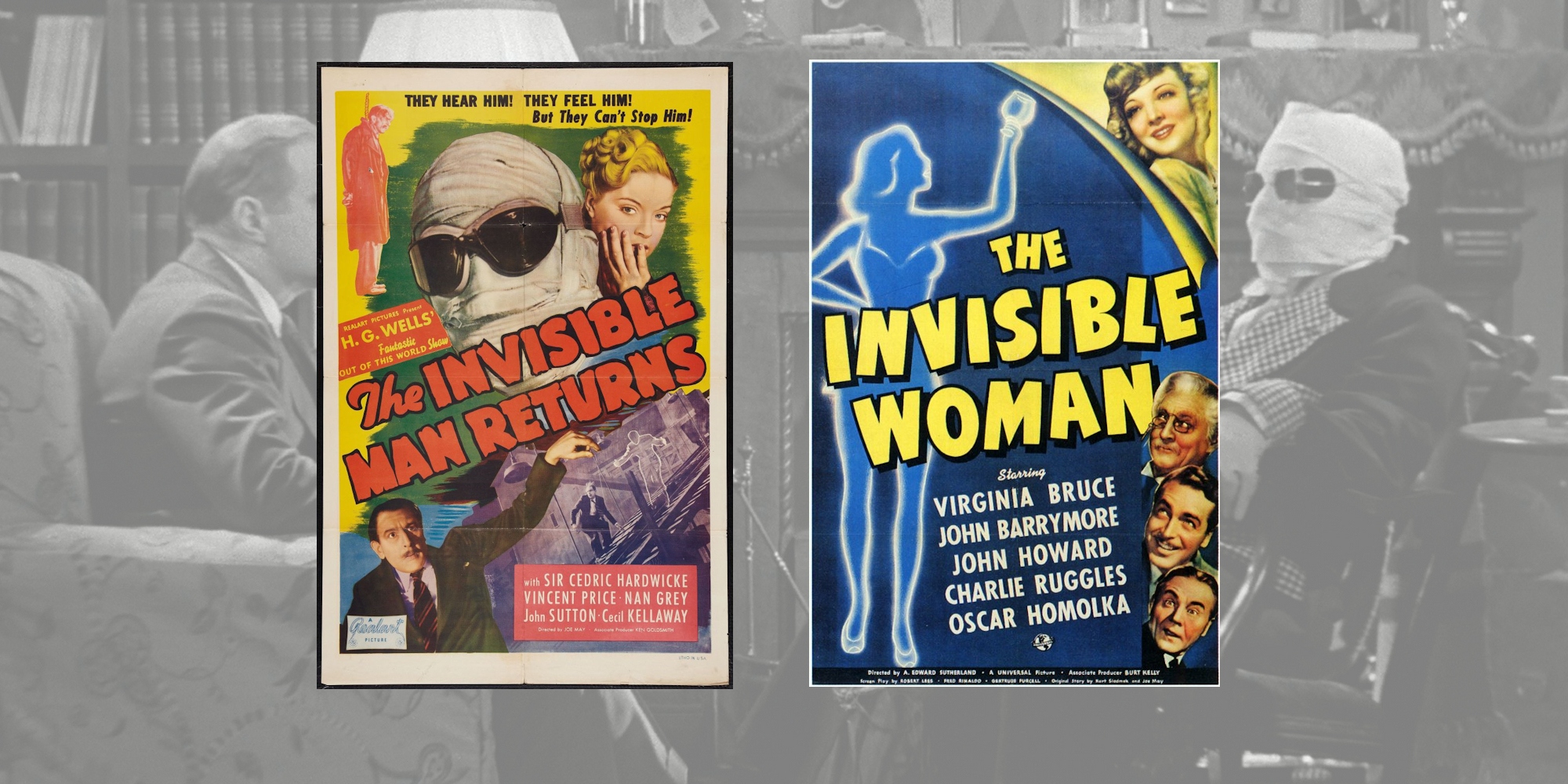

James Whale’s film adaptation of The Invisible Man was an immediate critical and commercial success, so the engine of the sequel factory was gassed up and set to work. Though Universal’s sequels have their merits and their own highs and lows, it’s safe to say that they’re all pale imitations of the original (Yes, a complexion pun, I couldn’t help myself). 1940 saw two film sequels, The Invisible Man Returns and The Invisible Woman. Returns come out relatively unscathed, with effects to match the first film, a capable screenplay by the talented and underrated Curt Siodmak (who also wrote The Wolf Man), horror legend Vincent Price in his first leading role, and first horror film. It’s a new story, but familiar territory all around. If we’re being kind to The Invisible Woman, we’ll simply say that it’s a screwball comedy about a woman who can turn invisible. Laughter and nudity humour and secret stolen kisses abound. That’s about it.

1942’s Invisible Agent and 1944’s The Invisible Man’s Revenge make for a strange double feature. The agent is an unabashed war propaganda film, with evil Nazis doing evil Nazi stuff, and Peter Lorre in a shameful turn in yellowface as an equally evil Japanese baron. Jon Hall plays the grandson of the original Invisible Man in a decent spy thriller that logically carries the premise into a wartime context. Revenge is refreshing in that it returns to the series’ roots with a properly villainous, murderous invisible protagonist, but the peculiarities of the casting and character names are baffling. Jon Hall returns in the lead, this time as Robert Griffin, a man completely unrelated to all the previous Griffins, in a story completely unrelated to all the previous films. And he’s evil this time. Maybe it’s like The Terminator and Terminator 2 but in reverse. Or something. The series returned to comedy with Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man in 1948, a film that may be the silliest and least substantial of the whole series, but ends up as one of the most entertaining, for its effective, nonstop use of invisible gags in the hands of capable slapstick comedians. Universal rolled out the trusty old invisible guy one last time for its classic cycle of films in a small cameo at the end of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein in 1951, voiced again by Vincent Price.

Universal Pictures shelved the Invisible Man film series, but the larger film and television world wasn’t nearly done with the poor man. One of the weirdest and laziest attempts to cash in on Wells’ original premise and the popular film series was MGM’s The Invisible Boy in 1957, essentially a feature-length commercial for Robby the Robot from the classic Forbidden Planet from the year before. It’s a film with truly rock-bottom production values, a baffling script, and featuring an utterly irrelevant invisible boy who is shoehorned into the story. NBC’s short-lived The Invisible Man tv series of 1975 was one of several series to actually cite Wells and his novel in the credits. As 70s tv shows with bowl-cut-sporting protagonists go, it’s not half bad, but its transformation of the lead character into a spy engaged in secret missions of espionage and crime-fighting is a far cry from the source.

That pesky “film rights in perpetuity” clause that Wells signed with Universal didn’t prove to be much of a problem for Sony Pictures when they made their thinly veiled adaptation Hollow Man in 2000, directed by Paul Verhoeven. The invisible man’s name is Sebastian Caine instead of Griffin, and the film is mostly set in a lab instead of a West Sussex village, but the brilliant scientist’s discovery of an invisibility formula, physical transformation, and subsequent delusions of grandeur and homicidal streak, are all oddly familiar. Where the film noticeably differs from previous efforts is in its portrayal of the invisible man as a certifiable, world-class pervwad. The very first thing Caine can think to do while invisible is to sneak around and sexually assault a sleeping woman. He later sneaks a peek at a woman on the toilet, and just for good measure, sexually assaults another sleeping woman. Oh, and did I mention the part where he sneaks yet another peek at a nearly-nude ex-girlfriend? The 2006 direct-to-video sequel Hollow Man 2 starring an invisible Christian Slater, continues the proud pervwad tradition. This time, not only does the invisible man exploit his condition to sexually assault women, but he graduates to “barely legal” territory when he spies on an undressing girl who looks so young I paused to wonder with mild concern whether I was committing a crime by watching the film. As a wink and a nod to the Wells estate, Slater’s homicidal invisible man is named Michael Griffin.

The Invisible Man, or something more or less like him, has made appearances here and there in other films and media, including the 1992 John Carpenter comedy Memoirs of an Invisible Man, Sony Animation’s Hotel Transylvania and its sequel, and Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s graphic novel series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and its 2003 film adaptation.

After dozens of attempts to re-cast and re-imagine and update and contemporize and sexualize H.G. Wells’ classic story, it is Whale’s original film that unquestionably stands tall above all others, and I argue two basic reasons for this. The first is that Whale properly understood the wry humour and charming prose of the novella and Wells’ acute observations of the inherently funny side of human nature. In the film, we see the barfly in the parlour, gingerly hammering away at the player piano and basking in unearned applause, Una O’Connor’s Mrs Hall shrieks hysterically at threats both real and imagined, and Griffin delights in singing nursery rhymes and playfully skipping like a schoolboy while assaulting and terrorizing the poor denizens of Iping. Compare this to the novel, filled with henpecked husbands, constantly bewildered and soused country bumpkins who speak in thread-barely discernible English, and respectable homeowners apparently more concerned with the very real and practical matter of preserving their pristine vegetable gardens than defending themselves from the vague and unlikely threat of an invisible maniac on the loose.

The second reason Whale’s film stands so triumphant is Claude Rains. Remember the opening song from Rocky Horror Picture Show, “Science Fiction/ Double Feature”? The simple declarative lyric says it best: “Claude Rains was the Invisible Man.” Rains really IS the Invisible Man, isn’t he? He’s simply marvellous, unforgettable, and a dozen other superlatives. Rains delivered a performance almost entirely with his voice, a voice is so rich, so salty, so creamy, so luscious as to impart a palpable mouthfeel of fine French butter on the palate. He was perhaps the most handsome, suavest, most debonair creature to have ever been loosed upon this world.

It may come as a shock that The Invisible Man was Rains’ film debut. Well, to be precise, he had played a bit part in a 1920 silent film that is now lost, but it sounds much more impressive to say that Griffin was his first role on screen (and it’s almost true). The performance relies on his years of experience as a stage actor in London and on Broadway to effectively portray a larger-than-life character whose face is shown on screen for all of five seconds. He uses his voice to magnificent effect, with his raucously rolling r’s and his unforgettable dry, mad cackle, to portray the manic mischief maker. All the more impressive considering the young Claude Rains grew up with a speech impediment and a thick Cockney brogue, both of which he had to unlearn through years of speech therapy and theatre training, and his voice dramatically changed yet again after suffering a gas attack in France during the Great War.

Almost as memorable as his voice is the febrile gesticulations that burst out of Griffin’s body during his sudden fits of rage, wherein he is utterly enraptured by himself. One can’t help but be reminded of the speech and performance patterns of Adolf Hitler at his rallies, and it’s probably no coincidence that the film was released just ten months after his appointment as Chancellor of Germany. Claude Rains’ performance is powerful and arresting, and it launched him into a prestigious film career that would include four Oscar nominations and roles directed by Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Curtiz, Frank Capra and David Lean. Tragically, while James Whale was the same age as Rains, Whale didn’t enjoy the same sterling reputation or live long enough to see The Invisible Man begin its meteoric rise to popularity on television. His suicide in 1958 came just months before his beloved Frankenstein and Invisible Man made their television debuts, where both films would reach larger audiences than they ever had before, and would begin to snowball into the untouchable masterpieces of classic horror that they are today.

Books associated with this article