The Hound of the Baskervilles / The Return of Sherlock Holmes

David Stuart Davies looks at the novel that suggested Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was not quite finished with Holmes, and the collection of stories that confirmed it.

In The Hound of the Baskervilles, one is presented with all the tried and trusted elements that make the Sherlock Holmes stories compelling reading – the cosy Baker Street opening, the pyrotechnical demonstrations of Holmes’ brilliant deductions, bizarre elements connected with a baffling mystery and a cruel and subtle villain of great cunning – but added to these is an extra ingredient which strengthens the mixture, making it both unique and thrilling. This extra ingredient is the world of the supernatural. In this novel not only has Holmes to contend with a flesh and blood villain but also a spectral hound whose ghastly shape is ‘outlined in flickering flame’. Arthur Conan Doyle’s clever marriage between the rational and the irrational in this Sherlock Holmes adventure is the main reason that this novel has retained its grip on readers’ imaginations ever since it was published. And that it is why it is a masterpiece.

Doyle had killed off his hero in the last story of The Memoirs called, appropriately enough, The Final Problem (1893). He had Holmes tumble off the terrible Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland locked in combat with his arch-enemy, the master criminal Professor Moriarty. So it was goodbye Sherlock Holmes. ‘I’m glad I’ve killed him,’ he announced. However, the method of Holmes’ demise meant that there was no corpse and this fact kept alive a flicker of hope for his devoted readers that the author might one day relent and pen further Holmes mysteries.

We now move on in time. In March 1901 Conan Doyle was taking a golfing break with a friend, Fletcher Robinson, at Cromer in Norfolk. As the story goes, one night in the hotel the two men fell to talking about ghosts and Fletcher Robinson told Doyle about the legend of a spectral hound that supposedly haunted the moors of Dartmoor. The author was taken with the story and it sparked his imagination. He saw in this legend the basis for an exciting story. Indeed he began working out the plot. In doing so Doyle realised that he needed a central character to unravel the mystery, a catalyst figure who brought together the various elements of the story – in other words, a brilliant detective. He accepted, no doubt with some reluctance, that this was quite simply a case for Sherlock Holmes. When the publishers heard this, they danced with joy. They knew that the name of the Baker Street sleuth would guarantee large sales.

The Hound of the Baskervilles was serialised in The Strand Magazine first. It ran for nine instalments from August 1901 to April 1902. One can only imagine the fiery enthusiasm and inspiration with which Doyle wrote the novel – a novel that was but a mere idea in March and a completed entity by August. The first instalment concluded with perhaps the most chilling interchange in all detective fiction:

“Footprints?”

“Footprints.”

“A man’s or a woman’s?”

Dr Mortimer looked strangely at us for an instant, and his voice sank almost to a whisper:-

“Mr Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!”

Readers were agog with excitement but had to wait a whole month before they got their hands on the next fragment of this thrilling tale.

In 1902 The Hound of the Baskervilles came out in book form and was a tremendous success. It has never been out of print since. It is the most famous of all Sherlock Holmes adventures and has been filmed and staged numerous times; but no dramatisation can equal the power of the novel in its creation of atmosphere and the description of the bleak Dartmoor location, with its strange granite tors and its treacherous mire that can swallow up man and beast and carry them down into its slimy depths.

The reappearance of Sherlock Holmes in The Hound gave readers, and in particular publishers, the hope that the detective would return permanently. The author was approached by several eager publishers with this in mind and when the editor of the American magazine Collier’s offered Doyle four thousand dollars per story, the author relented.

Collier’s magazine hoped that some of the stories would feature American settings or contain aspects of particular relevance and interest to readers in the States. The new series would also appear in The Strand Magazine in Britain. In a strange way, now that he had signed the contract to write a fresh series of Holmes’ adventures, Doyle relished the challenge and dismissed the fears of those who doubted that he could capture the brilliance of the earlier tales – his mother included. Having set to work, he wrote to her, ‘I don’t think you need have any fears about Sherlock. I am not conscious of any failing powers, and my work is no less conscientious than of old… I have done no Sherlock Holmes stories for seven or eight years and I do not see why I should not have another go at them.’

The focus of this first story, ‘The Empty House’, which provided the link between The Memoirs and The Return, is to explain what really happened at the Reichenbach Falls, to explain away Doyle’s ‘rash act’ as he referred to it. The murder mystery involving the death of Ronald Adair is really secondary to the re-establishment of Holmes back in London, back in his Baker Street rooms, back with Watson and back on the case. The fact that neither the details of Holmes’ escape from the supposed watery grave nor his three-year absence from England is entirely convincing does not matter at all. The main thing for readers then, as now, is that Holmes has returned.

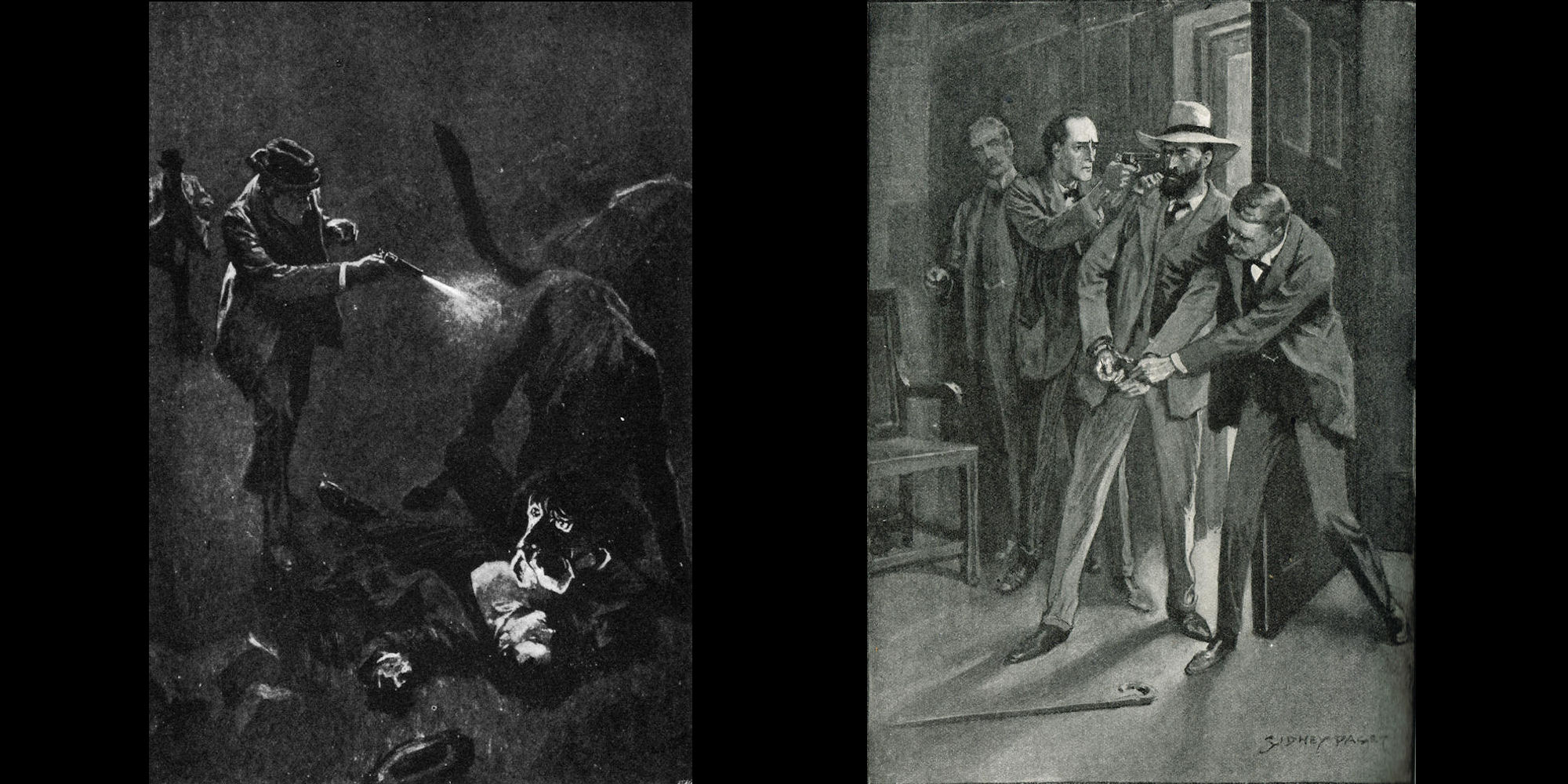

The tone and scope of this first story are reflected throughout the collection, where often dramatic set pieces take the place of the reasoning process that had been a strong feature of the earlier collections. Doyle’s writing always had a strong visual – almost cinematic – quality, and never more so than in The Return, which is crowded with vivid, indelible images. In ‘The Empty House’, for example, the scene of Watson’s fainting on seeing his old friend reveals himself by removing his fantastic disguise as an old bookseller, and the silhouette of Holmes against the blinds of 221B as Moran aims his deadly airgun are powerful vignettes. The Return is crammed with such moments: Jonas Oldacre bursting out of his hiding place on hearing the shouts of ‘Fire’ in ‘The Norwood Builder’; the sinister stick figure drawings which carried deadly warnings and Holmes clapping a pistol to the villain’s head in ‘The Dancing Men’; the eerily silent and mysterious bearded cyclist in ‘The Solitary Cyclist’; the murdered man transfixed to the wall by a harpoon in ‘Black Peter’; the shooting of the vile blackmailer in ‘Charles Augustus Milverton’; Watson’s rude morning awakening, the brutal murder of Sir Eustace Brackenstall and Holmes clambering on the mantelpiece to scrutinise the bell-rope in ‘The Abbey Grange’ are clear examples of this. There are more.

Like The Adventures and The Memoirs, the quality of the plots and the inventiveness varies from tale to tale, but they are nonetheless great stories. The character of this great fictional detective and his loyal chronicler shine like diamonds in a fog. The stage is filled with a cast of clients and villains who are vibrant and memorable. They are the fine vintage wine of Sherlockiana and I’m sure you will enjoy them.

Main image: Illustrations by Sidney Paget for ‘The Strand Magazine’ – The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) and ‘The Dancing Men’ (1905)

Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo, Historical Images Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Above: ‘The Adventure of the Dancing Men’ from The Return of Sherlock Holmes, 1905 edition Alpha Stock / Alamy Stock Photo

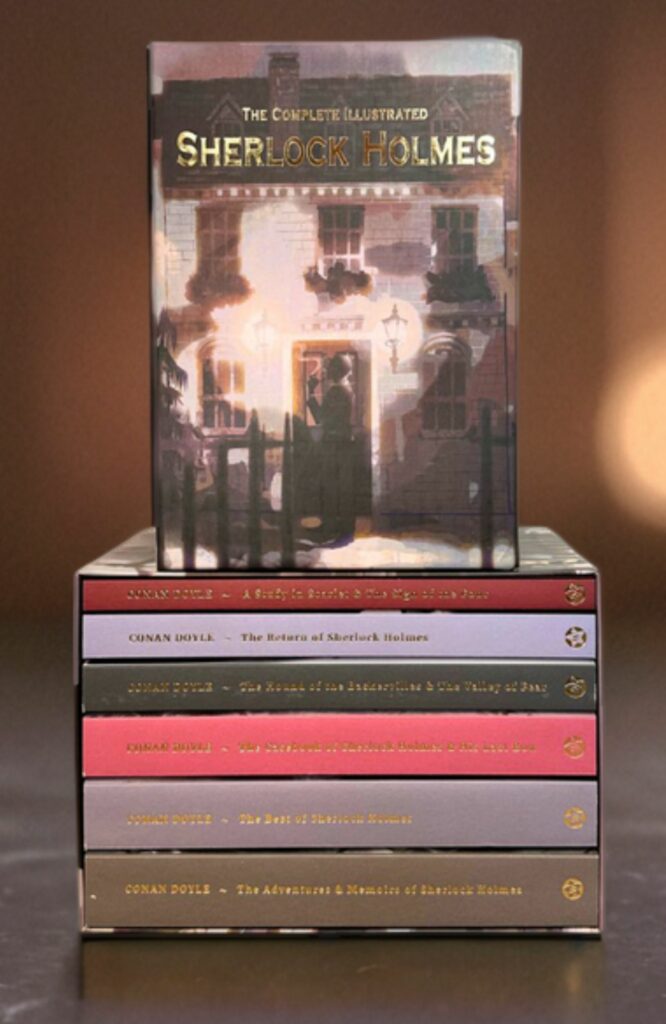

Books associated with this article

The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Hound of the Baskervilles & The Valley of Fear (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Return of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Complete Illustrated Sherlock Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle