David Stuart Davies looks at The Idiot

‘The Idiot’ was the third of Dostevesky’s classic novels. David Stuart Davies takes up the story.

‘The Idiot anticipates not just the concerns of twentieth century existentialist thought but heralds our modern age in general.’ Agnes Cardinal

The Idiot (1869 ) is one of a trio of great Russian novels penned by Fyodor Dostoevsky which also includes Crime & Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). These novels were widely read both within and beyond the author’s native country. This was partly due to the way he was able to explore human psychology and skilfully engage in a variety of philosophical themes embedded in an engaging and emotional narrative.

Dostoevsky was born in Moscow in 1821 and was an avid reader from his youth. He initially earned his living as an engineer, but his love of literature allowed him to earn extra income from translating books. This prompted him to write his first novel, Poor Folk (1845). He was arrested in 1849 for belonging to a literary group that discussed banned books in Tsarist Russia. This was regarded as a capital offence and he was sentenced to death. However, his life was spared at the last minute and he was sent to a Siberian prison camp for four years. On release he was forced to serve six years compulsory military service in exile. Later he honed his writing skills by working as a journalist and publishing and editing. He wrote many short stories in this period from 1849 -1859 but it was not until 1859 that he concentrated on novels and produced his trio of masterpieces, eventually becoming one of the most widely read and highly regarded Russian writers.

The Idiot plumbs the depths of the human spirit. The hero is Prince Myshkin, a nobleman belonging to an ancient Russian family. From his early youth he has suffered epileptic fits which have affected his physical and mental health. Dostoevsky deliberately set himself the task of depicting a ‘positively good and beautiful man’. Myshkin is a simple, sincere lovable character and completely without guile, which leads many of the more worldly, and one might add cynical, characters he encounters to mistakenly assume that he lacks intelligence and insight and so regard him as an idiot.

Within the narrative the author conducts the experiment of placing such a singular individual at the centre of the conflicts, desires passions, egoism and greed inherent in a so-called sophisticated society and examines the consequences that result for both the hero and those with whom he has become involved. Two women with diametrically different backgrounds, characters and motives fall in love with Myshkin. One is the daughter of a respected general; the other is a neurotic of easy virtue. These women present a dilemma to Myshkin. He will not marry the former because he regards himself unworthy of her and because of his mental instability he believes that he could not possibly bring her happiness. Instead, he intends to marry the other girl, Natasha. In taking her for his wife he sees himself saving her from the sordid life she lives. Myshkin’s sense of self-sacrifice is irrepressible. Events take a dark and dramatic turn when Natasha, moved by a selfless desire to spare him from making this terrible mistake, runs off with another man. The novel ends tragically with murder, death and the final erosion of Myshkin’s mental state. His sensitive spirit cannot endure the dramatic, painful turn of events and he becomes truly what he has often been accused of being, an ‘idiot’.

The theme of mental illness had autobiographical echoes for the author. For much of his adult life Dostoevsky suffered from a debilitating form of temporal lobe epilepsy. In 1867, the year he began work on The Idiot, he wrote to his doctor, ‘this epilepsy will end up carrying me off… My memory had grown completely dim. I don’t recognize people anymore… I’m afraid of going mad or falling into idiocy.’ It is clear that he transferred these fears and feelings into his character Myshkin, who, while aware he is not an idiot, sometimes concedes the aptness of the word in relation to his disturbed mental state. There is a knowing honesty and realism in the creation of this character that adds to the pathos and tragedy of his life which establishes the novel as one of the greatest interpretations of the human condition.

However, The Idiot was roundly criticized when it was first published. Reviewers in general found that the novel lacked realism. One critic claimed that some characters were ‘some kind of mysterious puppets hopping about as though in a dream’. Others had negative views on the novel’s apparently rambling narrative. However, through time, The Idiot has gained praise and recognition for the masterpiece it is. The twentieth century Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin regarded the structural asymmetry and unpredictability of plot development, as well as the perceived ‘fantasticality’ of the characters, not as any sort of deficiency, but as entirely consistent with Dostoevsky’s unique and ground-breaking literary method.

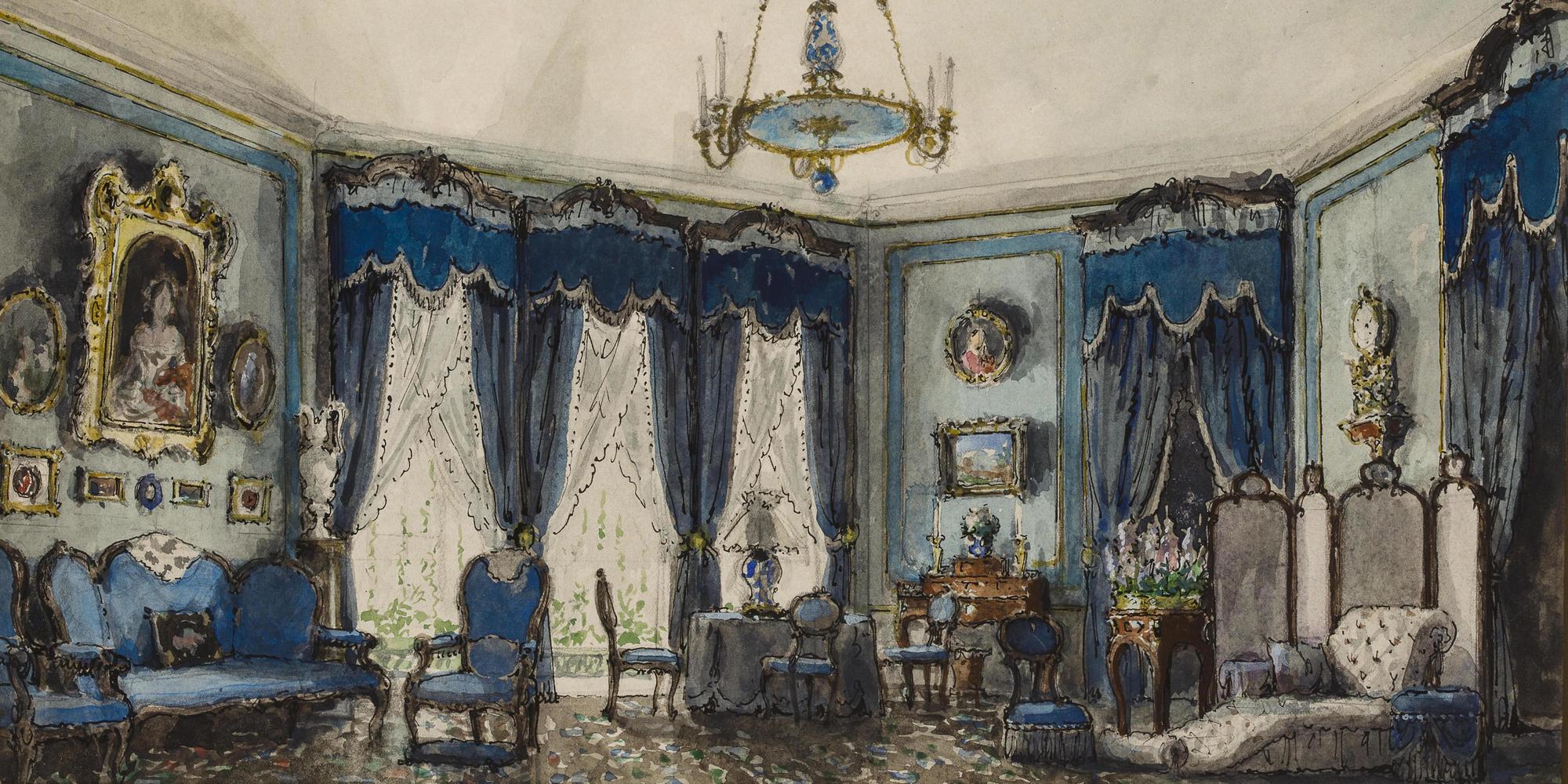

There have been several film versions of the novel, mainly produced in Russia, although there were was a Hindi version in 1992. In Britain, the BBC screened a five part adaptation in 1966 starring David Buck as Prince Myshkin and Adrienne Corri as Natasha. Playwright Simon Gray adapted the book for the theatre in 1992. A production for the National Theatre was staged at the Old Vic starring Derek Jacobi in the lead. That certainly is one play I would have loved to have seen.

When he began work on the novel, Dostoevsky wrote to his friend Maykov: ‘The idea is to depict an absolutely wonderful person. I don’t think there can be anything harder than that, especially in our time.’ This sentiment echoes through the years and is just as relevant today as it was then. For this alone, The Idiot is a magnificent modern read.

Image: Stage design for the theatre play The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Museum: PRIVATE COLLECTION. Author: Benois, Alexander Nikolayevich. Credit: Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article