David Stuart Davies looks at The Invisible Man

David Stuart Davies looks at the original novel that inspired (albeit tenuously) a new film released today.

‘People screamed. People sprang off the pavement… “The Invisible Man is coming!

Herbert George Wells (1866-1946) became an overnight literary sensation with the publication of The Time Machine. The success of this novel triggered an incredibly industrious and creative period of about six years when Wells wrote his most memorable and brilliantly conceived ‘scientific romances’. In quick succession, he published The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898) and The First Men in the Moon (1901). Each of these volumes is brilliant and ground-breaking in its own individual way, examining how the society of the time would react to amazing scientific advances.

The titular character, a scientist called Griffin discovers a method to make himself invisible but then is unable to reverse the process. In desperation he goes into hiding, turning up at an inn in the small village of Iping. With his face swaddled in bandages, his eyes hidden behind dark glasses and his hands covered even indoors, he checks in as a guest at The Coach and Horses. Because of his bandages, it is at first assumed that he is a recovering victim of some terrible accident. As he carries out experiments in his room to make himself visible again, Griffin becomes aggressive, arrogant and then violent. The horror of his fate has affected his mind. Because of his behaviour, he is forced from the village and driven to murder. He seeks the aid of an old friend, Kemp who refuses to help and so Griffin resolves to wreak his revenge.

Wells claimed that the inspiration for the novella was ‘The Perils of Invisibility’, one of the Bab Ballads by W. S. Gilbert, which includes the couplet:

‘Old Peter vanished like a shot,

But then – his suit of clothes did not.’

This is a notion mirrored in Wells’ story which though an entertaining read also raises some serious issues. Interestingly, the critic John Sutherland considered Wells and his contemporaries such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling as ‘writing boy’s books for grown-ups’ and identified The Invisible Man as ‘one such book’. This is perhaps too simplistic for there are certainly adult themes within the narrative. One thread relates the notion of immortality and the question of how humans would behave if there were no consequences to their actions. Griffin begins the novel as a decent law-abiding fellow but his invisibility secures him a great deal of freedom to behave as he wishes. As he states, ‘My head was already teeming with all the wild and wonderful things I now had impunity to do.’ He uses his invisibility to commit a series of immoral acts, including shooting a policeman, because he feels secure in not being observed or identified. In other words, he can get away with it. Though Griffin’s actions, Wells seems to suggest that many people would react in the same way which presents a bleak and damming view of human nature.

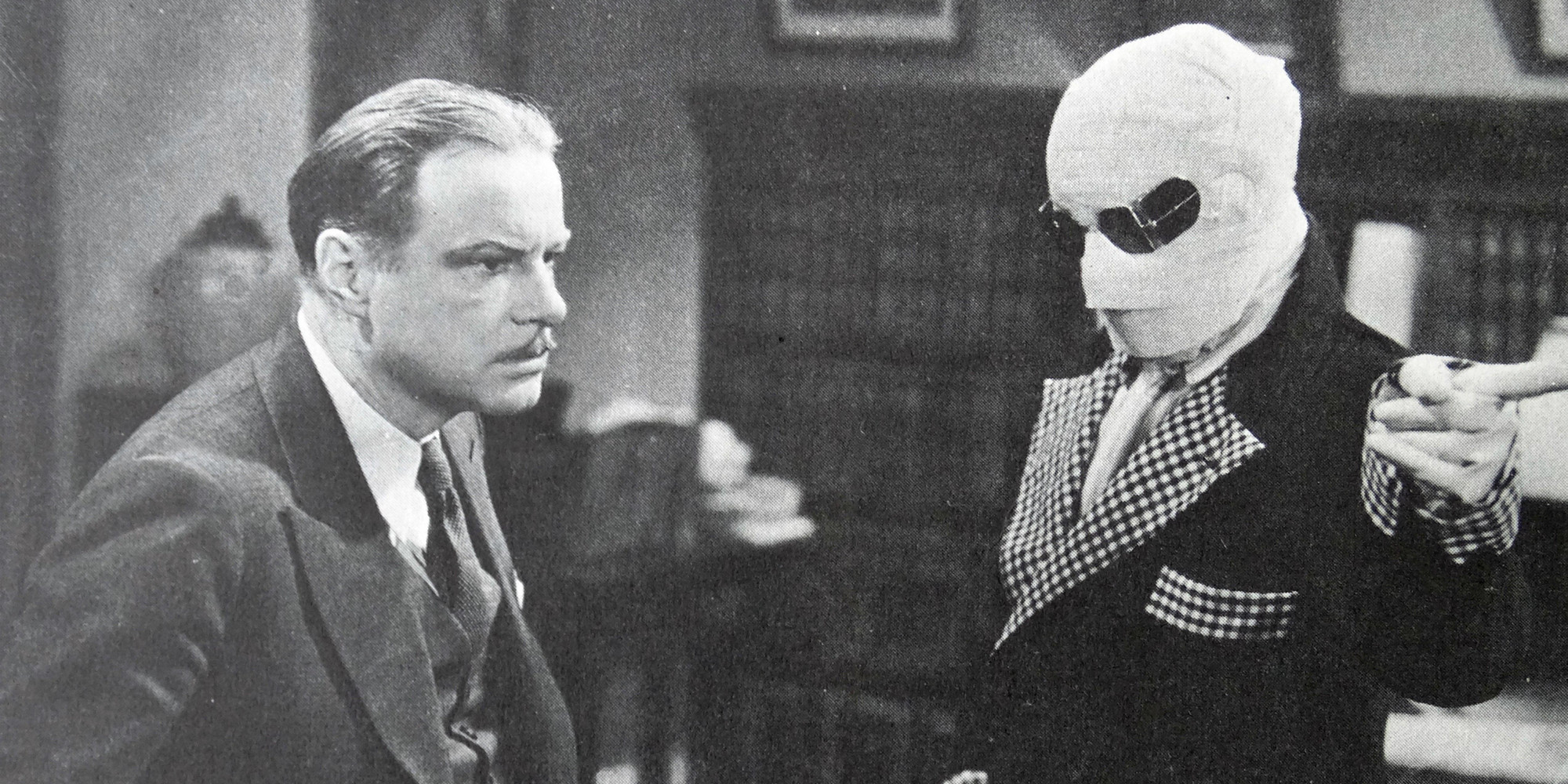

The Invisible Man was first serialised in Pearson’s Weekly in 1897 and as a novel later that year. The story was well received and helped establish Wells as ‘the father of science fiction.’ There is a fair amount of sly humour in the novel and this was effectively realised when Hollywood came to present a screen version in 1933. The movie, directed by James Whale who took great pleasure in injecting slightly surreal comedy into his films (See The Bride of Frankenstein), emphasised the farcical nature of Griffin’s dilemma in the early part of the movie, although it grows darker towards the climax. Claude Rains portrayed the Invisible Man although of course he is never seen, only heard, until the end when as he dies he loses his invisibility. What adds to the enjoyment of the film are the special effects created by John P. Fulton. The movie does justice to Wells’ novel following the main track of the author’s narrative. In 2008 this feature was selected for the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being ‘culturally, historically, and aesthetically pleasing.’ The film was a great box office success and spawned a set of sequels which reduced in quality as the series progressed ending up at its lowest point in 1951 when Abbot & Costello Meet the Invisible Man.

In the 1950s there was a popular British television series which featured a scientist, Dr Peter Brady, who becomes invisible after an accident in the laboratory. The programmes had only a tenuous link with Wells’ novel: Brady uses his special powers to solve mysteries and bring criminals to justice. There were other TV series to follow, including one in 1972 with David McCallum as the see-through scientist and in 2012 Darryl D. Moore played a thief who is given the means to become invisible and ends up working for a government agency.

Now there is a new movie for 2020. The plot involves an abusive boyfriend who fakes his own death and achieves invisibility in order to torment and torture his partner. While an effective horror movie, the only connection this movie has with H.G. Wells’ novel seems to be the title and the idea that someone can become invisible and behave in an immoral fashion.

I know filmmakers feel obliged to put their mark on literary material when transferring it to the screen but when they go too far away from the source, it becomes another entity altogether. For a real taste of the power and enjoyment of Wells’ tale, a viewing of the James Whale movie is recommended, but better still read the book.

Books associated with this article