The Legacy of Sherlock Holmes – Part One

David Stuart Davies looks at at the fictional detectives that followed in the footsteps of the most famous sleuth of them all.

Arthur Conan Doyle could never have imagined the effect he would have on the future of crime fiction when he created Sherlock Holmes. Ironically, it was a character of whom he soon tired. He regarded his master detective as a rather catchpenny figure and not as important as his own historical fiction. Nevertheless, Holmes brought him fame and wealth and as a result, he became the unofficial begetter of the detective story as we know it today.

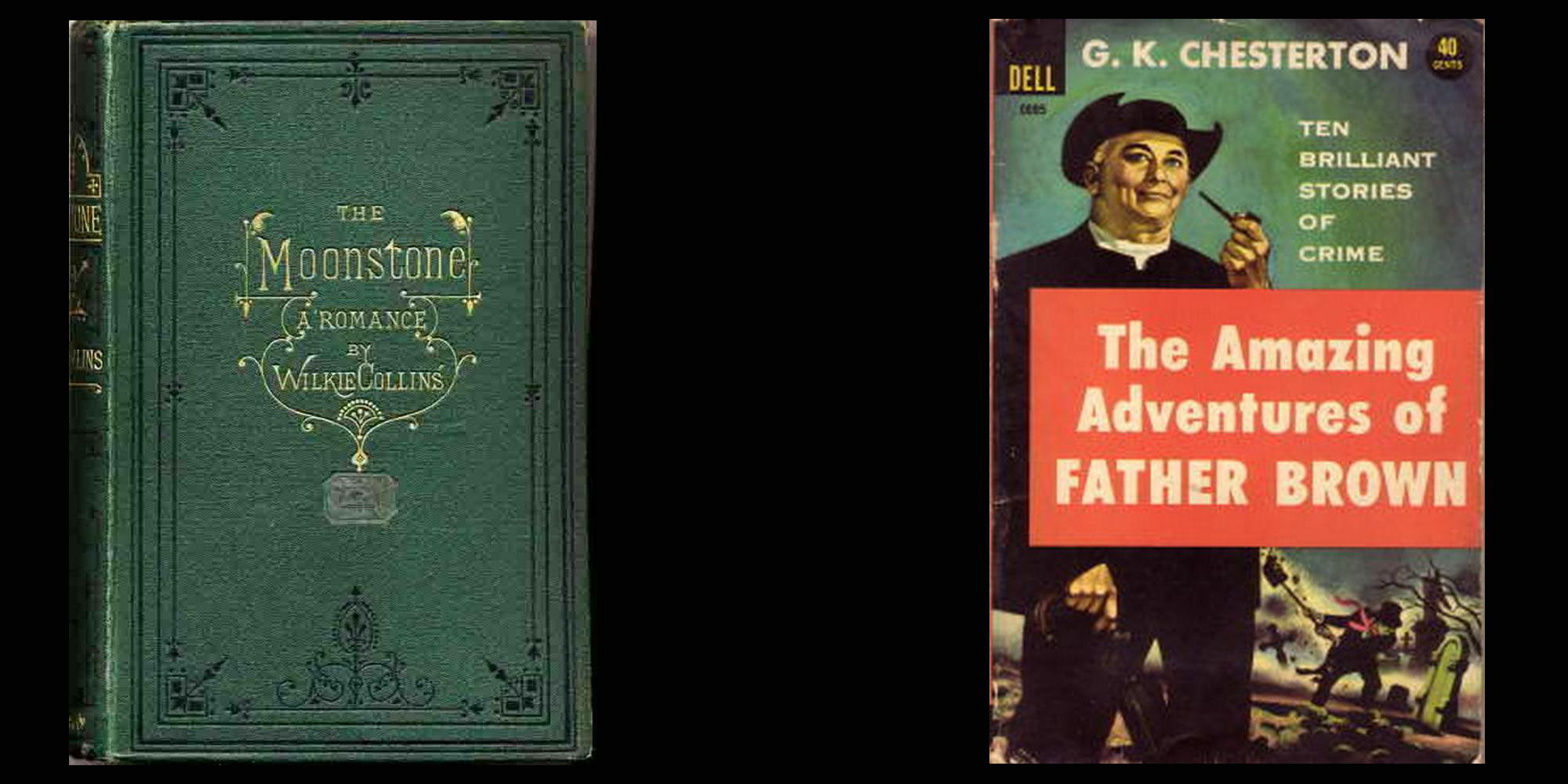

Certainly, there had been detectives in fiction before Doyle’s Baker Street hero appeared on the scene, most notably Edgar Allan Poe’s Auguste Dupin of The Murders of the Rue Morgue fame, Sergeant Cuff, the wily policeman from Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone and Sergeant Bucket in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. Indeed, Conan Doyle stole elements from all these characters and added ingredients of his own, especially colour, eccentricity and drama to create something very new and special – a unique sleuth who, when he appeared in the pages of the Strand Magazine in 1891, immediately caught the imagination of the burgeoning reading public. His fame grew quickly and sales of the magazine soared. Soon there were music hall songs about Holmes and a very successful stage play. Sherlock was the flavour of the month.

As a result of this popularity, other magazines and writers were keen to replicate Conan Doyle’s success and so a whole range of detectives began to appear in print who had certain similarities to Holmes in the sense that they were brilliant and could deduce things that others could not. They were not official policemen but private agents with various idiosyncrasies. It was as though Doyle had provided a flexible template for other authors to adapt to their own devices.

The trend was for writers to give their detective one peculiar trait which set him apart from the rest and made him unique in some way. A fine example is the blind detective Max Carrados created by Ernest Bramah. Despite lacking the benefit of sight, Carrados made use of his remaining senses in such a way that his blindness was often not immediately apparent to others. A wealthy, cultured and urbane man, he was an expert numismatist and a specialist in forgeries. Carrados could read print by finger-touch, use a typewriter and he smoked the most desirable and unobtainable cigars. He was assisted in his investigations by his manservant Parkinson who had been trained to be highly observant but without placing his own interpretations on what he observed. Carrados enjoyed the éclat of solving mysteries through his powers of perception, which in his case were heightened by a positive compensation for his lack of sight. Bramah’s stories also appeared in the Strand Magazine and at the time, just after the turn of the century, were as popular as the Holmes tales.

Another crime solver following closely in the footsteps of Sherlock was Martin Hewitt created by Arthur Morrison. Hewitt also featured in the Strand after Sherlock had been disposed of over the Reichenbach Falls and like Holmes, his stories were illustrated by Sidney Paget. Hewitt was a lawyer who discovered he had extraordinary deductive abilities and so he decided to become a private detective, with offices close to the Strand, near Charing Cross station. Hewitt was a stout, clean-shaven man of medium height and cheerful countenance. The first collection of Hewitt stories, Martin Hewitt, Investigator, is considered to be one of the important cornerstones in the development of the detective short story. Ellery Queen’s memorable Queen’s Quorum observed, ‘Of Doyle’s contemporary imitators, the most durable (indeed, the only important one to survive over the ages) is Martin Hewitt, the private investigator, a man of awe-inspiring technical and statistical knowledge.’

The most obvious copycat of Sherlock was, of course, Sexton Blake who was also domiciled down Baker Street where he was looked after by his housekeeper, a Mrs Hudson clone called Mrs Bardell. Blake was the creation of Harry Blyth, a jobbing hack who penned the first story, ‘The Missing Millionaire’ for a boy’s weekly paper, The Halfpenny Marvel in 1893. He was paid a nominal fee for the tale and the full copyright for the character. Since then well over a hundred writers have created exploits for Blake who was dubbed ‘the office boys’ Sherlock Holmes’.

By the turn of the century, the character of the stylish, individual sleuth with remarkable perception was firmly established. And in 1907, readers were introduced to Dr John Evelyn Thorndyke in the novel The Red Thumb Mark written by R. Austin Freeman. Thorndyke, the ultimate scientific detective, was described by his author as a ‘medical juris practitioner’: originally a medical doctor who turned to the bar and became one of the first forensic scientific sleuths. His solutions were based on his method of collecting all possible data and making inferences from them before looking at any of the protagonists and motives in the crimes. It is this method which gave rise to one of Freeman’s most ingenious inventions, the inverted detective story, where the criminal act is described first and the interest lies in Thorndyke’s subsequent unravelling of it. He was often assisted by his friend and foil Christopher Jervis, who usually acted as narrator. There were sixty novels and numerous short stories featuring Thorndyke and while the mysteries were invariably interesting and clever, the detective himself was rather a dull fellow.

Around this time there emerged another giant of the crime-solving genre in the shape of a dumpy clergyman who carried an umbrella and was in possession of an uncanny insight into human evil. This was Father Brown, a Roman Catholic priest created by G. K. Chesterton who, unlike Holmes, used methods which tended to be intuitive rather than deductive. He explained his method in The Secret of Father Brown (1927): ‘You see, I had murdered them all myself… I had planned out each of the crimes very carefully. I had thought out exactly how a thing like that could be done, and in what style or state of mind, a man could really do it. And when I was quite sure that I felt exactly like the murderer myself, of course, I knew who he was.’