The Pickwick Papers: David Stuart Davies looks at Dickens’ first novel

“That punctual servant of all work, the sun, had just risen, and begun to strike a light on the morning of the thirteenth of May, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-seven, when Samuel Pickwick burst like another sun from his slumbers, threw open his chamber window, and looked out upon the world beneath.’

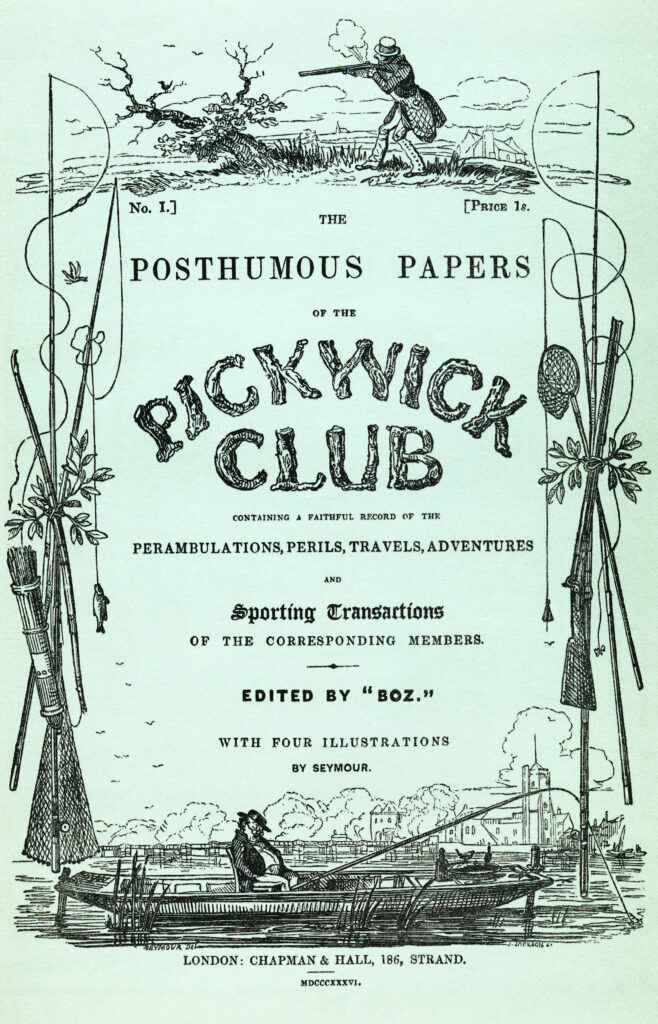

The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club

In 1836 the publishers Chapman and Hall commissioned a twenty-four-year-old journalist to write a novel recounting the comic adventures of an imaginary club. The young journalist was Charles Dickens and the resultant volume was The Pickwick Papers, which became a tremendous success and set Dickens forth on a remarkable career as a novelist of great renown.

The premise of this long, loosely structured novel is simple. Under the leadership of Samuel Pickwick, the rich and benevolent founder and general chairman of the Pickwick Club, he and several of the club members, romantic Tracy Tupman, poetic Augustus Snodgrass and sporting Nathaniel Winkle, venture from their London base on a journey of discovery, to take note of anything interesting that they encounter in their travels and report the findings to the other members. With this format, Dickens is able to create a variety of amusing episodes and introduce other characters to add to the colourful dramatic personae. These include Sam Weller, Pickwick’s sharp-witted Cockney servant; Alfred Jingle, a charming rogue who lives by his wits and cool nerve; and the medical student Bob Sawyer (‘Nothing like dissecting to give one an appetite’.) The characters are exaggerated and mostly caricatures, but there are some darker and more serious moments inserted into the narrative. For example, the antics of Slumkey and Fizkin show Dickens’ awareness of corrupt electioneering practices and at one point Pickwick himself is incarcerated in Fleet Prison. The scenes in the gaol near the end of the novel hint at those darker visions which Dickens would explore in his later works. The book also includes a number of moral or melodramatic tales such as ‘The Bagman’s Story’, ‘The Convicts’ Return’, ‘The Stroller’s Tale’ and others which counterbalance the comedy of the book.

Pickwick’s innocent and trusting nature repeatedly makes him the butt of comic adventures: struggling with a recalcitrant horse on the way to Dingley Dell; mistaking a lady’s bedchamber for his own; and, in the book’s most prolonged episode, unintentionally making his landlady, Mrs Bardell, believe he wishes to marry her and so provoking her into suing him for breach of promise. The now famous image of Pickwick, a short stout gentleman with a bulging tummy, bald head and a round face adorned by wire-rimmed spectacles was drawn by Robert Seymour who illustrated the first two episodes before committing suicide. The bulk of the other illustrations in the book were by Boz (Hablot Knight Browne) who provided drawings for most of Dickens’ subsequent novels.

One of the most charming episodes in The Pickwick Papers describes the Christmas at Dingley Dell where a wedding and other festivities take place. Christmas was a favourite time for Dickens and it features in many of his stories, most notably, of course, A Christmas Carol. However, it is in the Pickwick saga that the author first extols the joys of the festive season: ‘Happy, happy Christmas, that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days; that can recall to the old man the pleasures of his youth; that can transport the sailor and the traveller, thousands of miles away, back to his own fire-side and his quiet home.’

James Hayter

The novel was first published in monthly parts from April 1836 to November 1837 as ‘The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club Containing a Faithful Record of the Perambulations, Perils, Travels, Adventures and Sporting Transactions of the Corresponding Members.’ The book immediately caught the imagination of the public and it became a runaway success, prompting the appearance of bootleg copies and unlicensed theatrical performances, and even Sam Weller joke books. And of course, the little-known journalist who penned this work became a famous author. Before the last chapter of Pickwick was published, Dickens was already at work on Oliver Twist.

Pickwick and the members of his club have entered the consciousness of all who love English literature. The novel has been dramatised in many forms over the years. There were two silent movies in 1913 and 1921 – now both lost. Orson Welles took on the mantle of Pickwick for a radio adaptation in 1938. Perhaps the best cinematic version was the 1952 movie in which James Hayter became the embodiment of Samuel Pickwick as presented in the prose and illustrations from the book. Most of the comic and dramatic episodes from the mammoth narrative were included in the movie, which boasted an excellent cast: Harry Fowler (Sam Weller); Nigel Patrick (Alfred Jingle); Alexander Gauge (Tracy Tupman); and Hermione Baddeley (Mrs Bardell).

BBC TV gave us their take on the novel in 1985. The twelve-part adaptation starred Nigel Stock in the lead and Phil Daniels as Sam Weller. Perhaps the most unusual version was Pickwick the musical with a book by Wolf Mankowitz, music by Cyril Ornadel and lyrics by Leslie Bricusse. It was a great success in London where it starred Harry Secombe as Pickwick and Roy Castle as Weller. It did less well in the States but spawned the popular song ‘If I ruled the World’, which was recorded by many singers.

The Pickwick Papers still has the power to entertain. Indeed one critic writing in 2015 observed that, in writing the novel Dickens created a fresh form of literature: ‘a new one that we have learned to call ‘entertainment.’’ The actor and director Simon Callow summed up the book’s brilliance and its appeal when he described it as: ‘A great hokey-cokey of eccentrics, conmen, phoney politicians, amorous widows and wily, witty servants, somehow catching an essence of what it is to be English, celebrating companionship, generosity, good nature, in the figure of Samuel Pickwick Esquire, one of the great embodiments in the literature of benevolence.’

Main image: Frontispiece showing ‘The Pickwick Club’ from ‘The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club’; illustration by Cecil Aldin (1870-1935). Credit: AF Fotografie / Alamy Stock Photo

Images in text: (1) Cover of the original edition. Credit: Lordprice Collection / Alamy Stock Photo (2) James Hayter in the 1952 film version. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article