The War of the Worlds – reviewed

The BBC series has received mixed reviews. David Stuart Davies gives his thoughts on the merits of the new adaptation of the War of the Worlds.

‘One of the hardest things to flesh out in the adaptation process is to populate the story with characters and make it their personal journey.’ Peter Harness, the screenwriter of the BBC production.

The War of the Worlds, the classic science fiction novel by H.G. Wells, was published in 1898. It concerns the invasion of Earth by the Martians. The Red Planet is dying and the lush and verdant earth is seen as a suitable alternative home for the alien beings from Mars. Part of the thinking behind the narrative was Wells’ concern regarding the ruthless colonisation by the British of various parts of the globe. He believed that we were the invaders, just like the Martians.

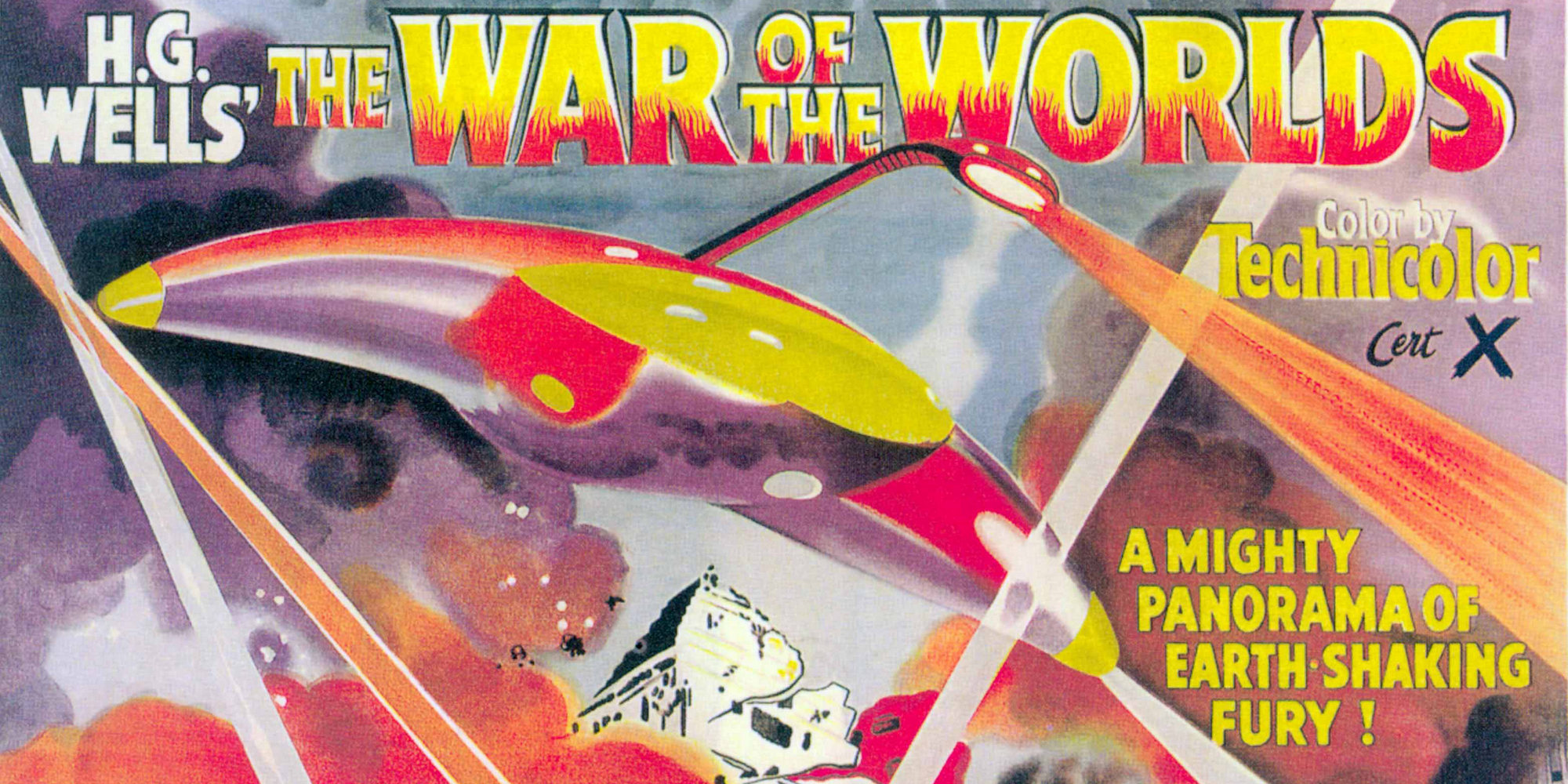

There have been two film adaptations of the novel: one in 1953 starring Gene Barry and one in 2005 with Tom Cruise. Both versions moved the location of the story to America and updated it to the modern-day. The main emphasis of both these vehicles was the drama of the invasion and special effects.

Now the BBC has presented us with a new three-part television version set in England in 1906. The move from the Victorian to Edwardian period was a time when the international conflict was leading us to a world war. It was visually spectacular and wonderfully photographed but it has met with mixed reviews mainly because the screenwriter Peter Harness has added details and a subplot which is not in the novel. Harness observed that the book reads ‘more like a piece of reportage’. This is true and that is probably why the most effective version of the novel had been Orson Welles’ infamous radio broadcast in the 1930s when the tale was presented as a real-life radio report. To be fair, Harness sticks to the basic skeleton structure of Wells’ plot but places fresh meat on the bone. I believe that his additions have enriched the story and humanised it. In the novel, only one character, the scientist Ogilvy, is given a name, and there are no real interpersonal relationships to engage the reader. As a novel, this works because it helps to maintain the documentary feel of the narrative, but for a dramatized version the viewer must be emotionally involved not only with the maelstrom of events on screen but also with the individuals facing the horrors of the conflict.

At the centre of Harness’ script are a young couple George (Rafe Spall) and Amy (Eleanor Tomlinson), who form the focus through which we see the events and repercussions of the invasion. The opening episode, which was rather slow, concentrated too much on this couple’s pariah status in the community. They are unmarried and living together and this made them moral lepers in the eyes of the inhabitants of Woking. This was a nod to Wells’ own personal circumstances but it also illustrated the theme woven by through the text of how suspicious and critical society was of those who were different or unconventional. This is linked to the innate criticism of the British colonial policy, expounded clearly by George in the final episode when he comes to believe that the Martian invasion is ‘a punishment’. As Wells’ mouthpiece George asserts that the Martians were doing what the British Empire had done for decades: ‘we move across the earth and we take land.’ This view was angrily dismissed by George’s brother, Frederick (Rupert Graves), a pillar of the British government, a blinkered group of politicians who in their arrogance were very slow to realise the full extent of the threat the Martians brought to Britain.

I was uncertain about the use of flash-forwards to the future after the alien conflict was over and the earth itself was reduced to its own red smoke-filled, weed-infested no-man’s-land of a planet. In some respects, it gave the game away for the astute viewer would realise that George was dead and no happy ending was in view – unlike the novel where the family are reunited. Amy’s unborn child, George’s son, is now seven, indicating how long the effects of the Martian war had wreaked disaster on the land. At this stage of their lives, Amy and her son are only just surviving, living in poverty and relying on food banks. Nevertheless, these scenes did not reduce the effectiveness of the main thread of the drama: the exodus from London of refugees in a desperate bid to escape the Martian menace. And what a menace they were. These creatures were wonderfully realised, from their huge towering tripods which emitted black poisonous smoke, laying the towns and countryside to waste, to the actual Martian beings themselves. Unlike those described by Wells as being slimy with various tentacles, these resembled large spiders with fierce beaks which seemed to suck the flesh from their victims. In the final episode Amy, George, Frederick and an old lady they have met on their travels are trapped in a deserted building which is being patrolled by two of the spider-like Martians. The old woman, dying of typhoid after drinking fetid water, falls victim to one of the Martians who stabs her with its beak and pulls her away to devour her in some dark corner. It was a wonderfully tense and chilling scene worthy of any self-respecting horror film.

The cast is excellent, but special mention must be made of Eleanor Tomlinson, who conveyed so much emotion through subtle facial gestures and spare dialogue.

I may be in the minority in raising my hand to give a thumbs up to this thoughtful, visually stunning and often exciting version of The War of the Worlds, but I genuinely believe H. G. Wells would have approved.

Books associated with this article