Sally Minogue look at The Waves

‘Now is life very solid, or very shifting?’ Sally Minogue considers Virginia Woolf’s ‘The Waves’.

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

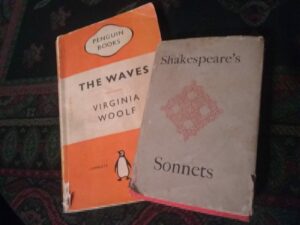

So do our minutes hasten to their end. (Sonnet 119)

We are all turning to Shakespeare’s sonnets at the moment, exquisite poetic embodiments of the remorseless depredations of time and the (for us, sudden) ever-presence of ‘that churl Death’. ‘Yet’, the poet also announces, ‘to times in hope my verse shall stand’ since ‘Not marble, nor the gilded monuments / Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme’. Just as we think he has condemned us to a bleak, barren existential landscape, the power of art comes to the rescue, often in the final couplet, to remind us that we are indeed still reading the lines of a man who died over 400 years ago. And we are remembering too the man or woman embodied in those lines, the loved one to whom they are written.

Virginia Woolf, also much possessed by death, often has recourse to Shakespeare in her writing; in her diary entry for April 24th 1928, just after she has been reading Othello, she says of him, ‘He abounds. Other writers stint. As usual, impressed by Shakespeare.’ So when she called her seventh novel The Waves, Sonnet 119 must surely have been in her mind. That is not quite the same as saying that there is an intended reference; if there is, it is more subterranean than, say, the direct quotation ‘Fear no more’ from Cymbeline, the motif running through Mrs Dalloway. Furthermore, the novel that became The Waves started life as The Moths, a title and a conception first mentioned in her diary as early as June 18th 1927 – ‘the play-poem idea; the idea of some continuous stream, not solely of human thought, but of the ship, the night, etc, all flowing together’. In fact the speedy writing of Orlando intervened, finished in March 1928, proofreading in June, and before that novel is even published, she notes (August 12th), ‘The Moths hovers somewhere at the back of my brain’. In November she is turning it over in her mind, but unresolvedly: ‘Yes, but The Moths? That was to be an abstract mystical eyeless book: a playpoem. … one reviewer says that [my style] is now so fluent and fluid that it runs through the mind like water. … Shall I now check and consolidate, more in the Dalloway and Jacob’s Room style?’ Fascinating to hear a great writer debate with herself in this way, a creative conversation which continues in the diary through to the end of the year. Then in her New Year entry, January 4th 1929, we see her acceptance that she must make her subject the movement between the fluid and the fixed: ‘Now is life very solid or very shifting? I am haunted by the two contradictions. This has gone on forever; will last forever … – this moment I stand on. Also, it is transitory, flying, and diaphanous. I shall pass like a cloud on the waves.’ There is a lot more of this sort.

Death, then, is not the primary preoccupation in this novel. At its forefront, and embedded in its experimental technique, is an abiding concern with perception, its variability from one consciousness to another, and the effect this may have on our understanding of reality. The arch-preoccupation of modernism, indeed, and of Woolf in particular. And in one of her last diary entries, before she actually starts writing the novel, she asserts with supreme confidence: ‘Of course I can make her [the subject] think backwards and forwards. … Also I shall do away with exact place and time.’

Death, then, is not the primary preoccupation in this novel. At its forefront, and embedded in its experimental technique, is an abiding concern with perception, its variability from one consciousness to another, and the effect this may have on our understanding of reality. The arch-preoccupation of modernism, indeed, and of Woolf in particular. And in one of her last diary entries, before she actually starts writing the novel, she asserts with supreme confidence: ‘Of course I can make her [the subject] think backwards and forwards. … Also I shall do away with exact place and time.’

That doing away, and that backwards and forwards, have caused readers some trouble. The narrative is unanchored. As Woolf herself writes of her method, ‘Who thinks it? And am I outside the thinker?’ (Diary, September 25th 1929) In spite of its apparent division into the different perceptions of delineated (and named) characters/consciousnesses, and a certain amount of sharing of the same place and time between them, the predominant sense is of a floating off and away, or conversely of the sinking of the self into something other. Louis, examining the flowers, suddenly becomes one:

I hold a stalk in my hand. I am the stalk. My roots go down to the depths of the world, through earth dry with brick, and damp earth, through veins of lead and silver. I am all fibre. All tremors shake me, and the weight of the earth is pressed to my ribs. Up here my eyes are green leaves, unseeing.

A negative capability Keats would have been proud of! Yet while this is close-knit prose, tied to a sense of actuality, it is untethered from normal reality. Louis’ perception of the world around him has dissolved into being the world around him, and the sense of dissolution in the narrative makes it quite hard for readers to keep their bearings. Even though the names of the ‘speakers’ are frequently mentioned, it takes some time to locate the identity of each consciousness – indeed part of the point is that we shouldn’t too closely locate it. So the reader is made to work hard.

There are however many allied rewards. Very often as I was reading I smiled in recognition of the way Woolf pins down an emotion, a response, a perception – sharing with her a conspiratorial smile even, a nod of shared understanding. So while she is carefully delineating individual consciousnesses and their different perceptions of ‘the world’, she is also linking those to some sort of commonality of experience or awareness. The novel begins with six children, growing into their adult selves, and in their later incarnations in the novel, they recall or reflect on their earlier perceptions. Susan, it appears, finds in adulthood the immense satisfaction of motherhood, and for a couple of pages celebrates this, seeing how ‘the violent passions of childhood, my tears in the garden when Jinny kissed Louis, my rage in the schoolroom, which smelt of pine, my loneliness in foreign places’ have transmuted into ‘peaceful, productive years. I possess all I see. … I have netted over strawberry beds and lettuce beds and stitched the pears and the plums into white bags to keep them safe from the wasps. I have seen my sons and daughters, once netted over like fruit in their cots, break the meshes and walk with me, taller than I am, casting shadows on the grass.’ But on the very next page she admits ‘Yet sometimes I am sick of natural happiness, and fruit growing, and children scattering the house with oars, guns, skulls, books won for prizes and other trophies. I am sick of the body. I am sick of my own craft … the unscrupulous ways of the mother who protects, who collects under her jealous eyes at one long table her own children, always her own.’ Woolf isn’t saying that one or the other view is right here; nor does one make the other less meaningful. Both are right; both are felt. The world is a complex place, but the world isn’t even or only the world. It is fractured into myriad impressions of it.

This then is at the heart of The Waves, that our various understandings and experiences of reality are constantly shifting, and with that, reality itself can seem insubstantial, evanescent. The power of the writer, and of this writer in particular, is that s/he can capture that, however fleetingly, and in doing so provides, through language, a moment of shared understanding for the reader.

The sunlight on the garden

Hardens and grows cold,

We cannot cage the minute

Within its nets of gold.

Thus Louis Macneice, written in 1936, five years after the publication of The Waves in 1931. In 1936 Woolf was revising her penultimate novel, The Years. The atmosphere was politically febrile. ‘Hitler has his army on the Rhine’ she reports in her diary (March 13th), and ‘it’s odd, how near the guns have got to our private life again. I can quite distinctly see them and hear a roar, even though I go on, like a doomed mouse, nibbling at my daily page’.

Anyone who is writing, and anyone who’s reading, may feel like that at the moment – we are ‘nibbling’. The sense of unreality, of encroaching meaninglessness, can make all of this seem just ‘Words, words, words’. Against that, we have not just Woolf’s great body of work but that of all those writers to whom we are now turning. Whether they seek to describe and contain a knowable reality, or to gesture towards its ultimate unknowability, here we are, still reading them, thinking, like Woolf, backwards and forwards, doing away with exact place and time, and voyaging beyond our temporal borders into their imagined worlds.

I have conflated three of Shakespeare’s sonnets in the above. The first quotation is from Sonnet 119; I have interspersed afterwards lines from Sonnets 47 and 98. All the sonnets are currently being offered in succession in reading on Twitter by Patrick Stewart @SirPatStew – though, charmingly, he has just admitted that he finds Sonnet 5 too difficult to understand, so he has proceeded to Sonnet 6.

The reference to ‘negative capability’ is from Keats’s Letters; he regarded it as the first necessary quality of a poet to be able to negate himself and surrender to the nature of something other.

Louis Macneice’s ‘Song’ (or ‘The sunlight on the garden’) was written in 1936 and first published in The Listener in 1937. Its first appearance in a collection is in The Earth Compels, 1938. It is much anthologised.

‘Words, words, words’ is Hamlet’s reply to Polonius’ question, ‘What do you read, my lord’, Act 2, Sc. 2.

Who thinks it? And am I outside the thinker?

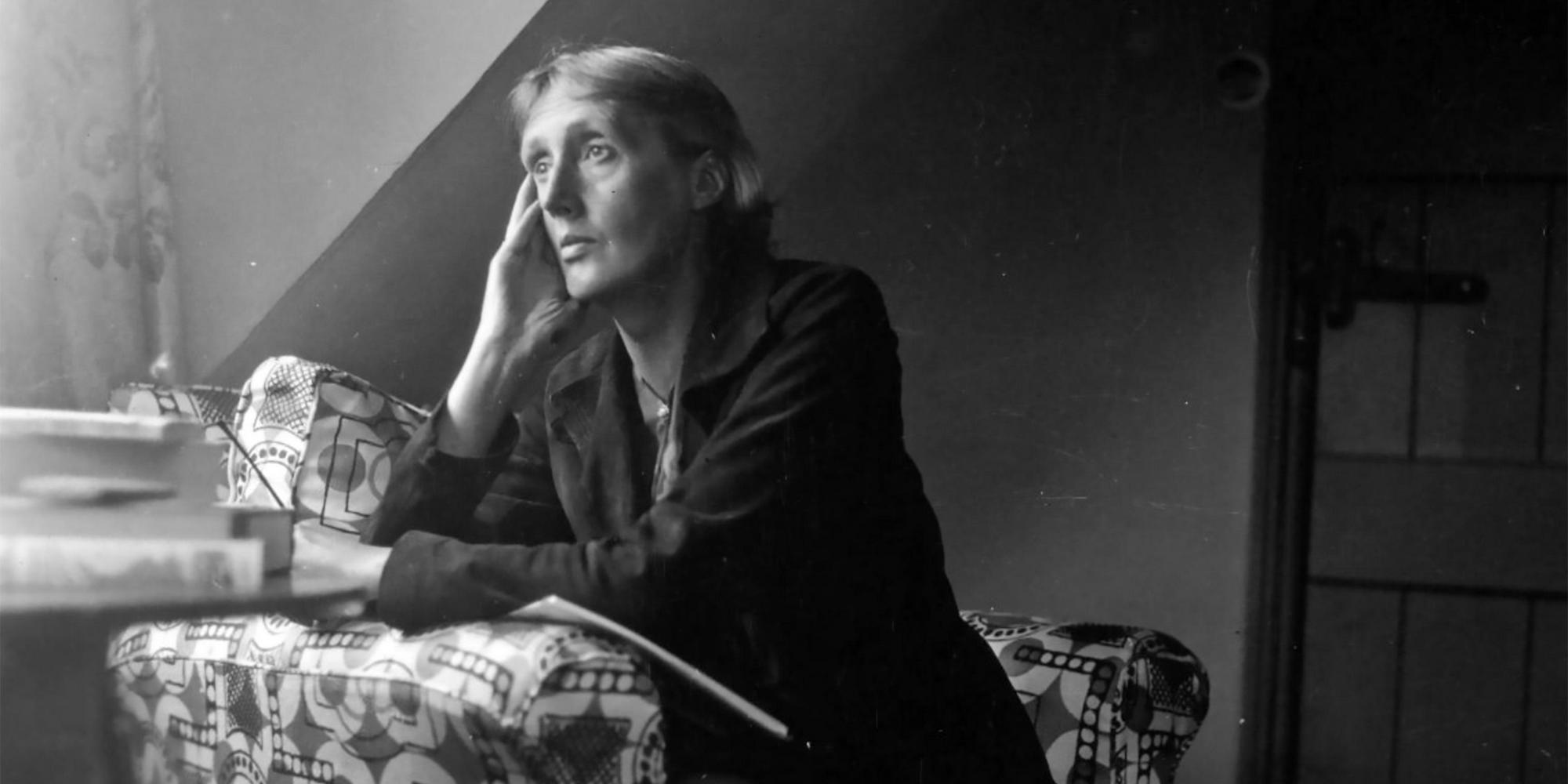

Woolf

Main Image: VIRGINIA WOOLF (1882-1941) English novelist about 1928

Contributor: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article